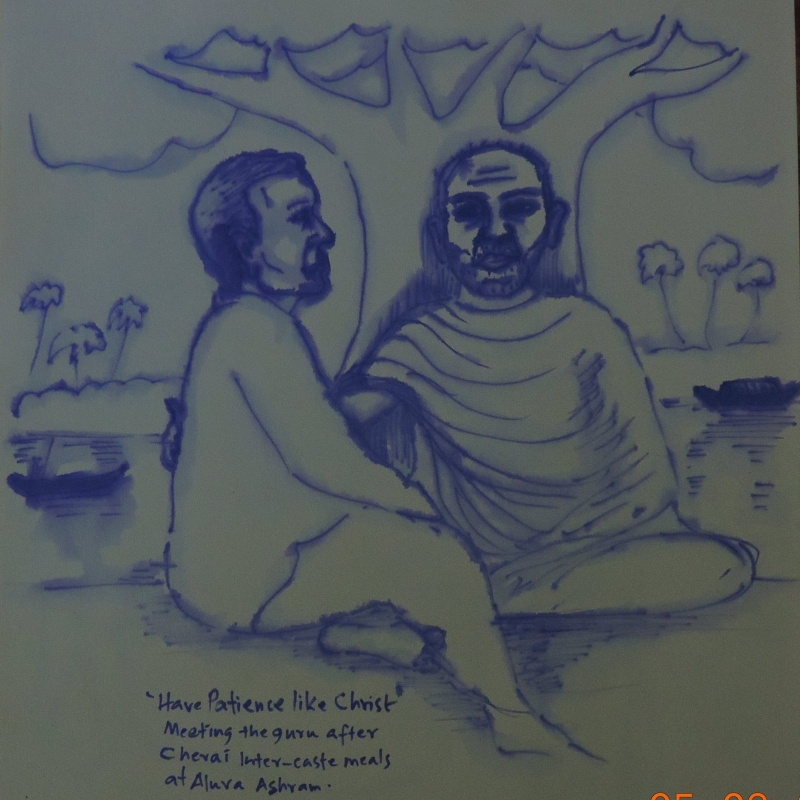

Sahodaran Ayyappan (1889–1968), a leading cultural activist, editor, and poet in the early and mid-20th century in Kerala, revolutionised the aesthetics and politics of the Malayalam language and poetry in an unprecedented way. Narayana Guru allowed only one disciple to change his motto—it was Sahodaran Ayyappan who said, ‘No caste, no religion and no god; but ethics, ethics and ethics; most appropriately and accordingly’ (Sahodaran 34; Sekher 2012: 195). Sahodaran was a socio-cultural revolutionary who practised and implemented his master’s philosophy and message. It is interesting to remember and reflect on his cultural and political interventions and writing as we celebrate the centenary of his 1917 Cherai inter-caste dining protest (panthibhojanam/misrabhojanam). Sahodaran also spearheaded other defiant acts to annihilate caste and untouchability in Kerala, using the ethical teachings of his master, Narayana Guru, the visionary of Kerala modernity.

Sahodaran’s poetry and prose have shaped Kerala’s literary and journalistic sensibilities in the context of early 20th century colonial modernity. He was a leading disciple of Narayana Guru, and like his master’s, his own poetic works have not been adequately studied or written about. He revived many democratic, secular, and ethical ballad and folk traditions of poetry in Kerala by rewriting them—the most famous of his works is probably his rendering of the legendary medieval song, 'Song of Onam', by Pakkanar. His first major anthology, originally published in 1934, has a section called 'Buddha Kandam' (The Book of Buddha), comprising 12 poems about the Enlightened One and the relevance of his dhamma (ethics in a neo-Buddhist paradigm) to Kerala’s cultural context. Sahodaran was also instrumental in persuading Muloor to author one of the earliest Malayalam translations of the Dhammapada (The Teaching of Buddha) directly from Pali. Almost 70 of Sahodaran’s poems were published across a few anthologies (Sanu 1980; Subramanyam 1973).

Sahodaran Ayyapan started a journal named 'Sahodaran', a moniker he later prefixed to his own name. He was born in an Ezhava household called Kumbalatu Parambil, in Cherai, in the northern part of Vypin Island. The journal logo was a pipal (Ficus religiosa or sacred fig) leaf, and it was published at a press in Mattanchery. Sahodaran, along with other poets like Pandit Karupan and Muloor, called Nanuguru ‘Sree Narayana Buddha’, or the Kerala Buddha, in verse (Sekher 2012:199; Sahodaran 51). Karuppan and Sahodaran played a crucial role in popularising the vision of the human community of their master among the common people of Kochi.

Sahodaran’s poetry delved deep into the worldly and ethical. He wrote extensively about enlightenment values such as freedom, equality, justice, ethics, and rationality, as well as on statecraft and the complexities of life. He composed verses about the October Revolution in the early 20th century and sang about French Revolution values in Malayalam. Using popular verse and musical traditions, Sahodaran informed the common people about the teachings of the Buddha and Nanuguru, as the cultural legacy of Buddhism had been erased from Kerala during the Varnashrama dharma (the hierarchic system of social stratification enshrined in the Rigvedic Purushasukta endorsed by the Smrutis and Srutis and Gita in particular) conquest in the Early Middle Ages. His poems first introduced the word ‘comrades’ into the linguistic culture of Kerala, and his signature way of addressing readers as ‘brothers’ touched people. He used the word Saghakkale to mean comrades.

Thus, Sahodaran was an inclusive writer and public figure who embraced emancipatory values and ideals derived from various liberal and left streams in a democratic and polyphonic way, following in the footsteps of his master. His poetry was counter-cultural and counter-hegemonic, in that it was strategically anti-caste and counter-Brahmanical. It was a poetics of impermanence, a unique combination of anitya (Buddha’s theory of impermanence) and anekanda (Jainist theory of inter-dependence). He also revived Buddhist culture in Kerala through his poetic works, and he pioneered the Neo-Buddhist movement in Kerala along with C.V. Kunjuraman and Mitavadi C. Krishnan in the 1920s and 1930s, like Ayyothee Thasar in Tamilakam. Like Thasar’s Indirar Desa Saritram (The History of Indirar (Buddha) Land, published in the late nineteenth century) Sahodaran composed a verse on the history of Buddhism in Kerala. He also created transformative cultural public spaces for inter-caste-marriage and inter-caste-dining through his poetry, which also reflected the polyphonic, egalitarian, and ethical philosophy and syncretic social praxis of Nanuguru (Guru 2006; Sekher 2016).

Sahodaran was the first poet in Kerala to challenge—in poems like 'Gandhi Sandesam'—the incipient elite nationalism of the 1930s and 1940s by critically representing Gandhi and his nationalist paternalism and worldview based on varnashrama dharma. He was also the first major writer from Kerala to recognise the merit of Ambedkar and Navayana (Neo Buddhism of Ambedkar or political Buddhism) in the early 1930s (Ambedkar 2002; Omvedt 2004). In 'Jati Bharatam' (Caste India), he prophetically declares the emergence of the Ambedkar age in Indian society, culture, and democratic politics in the near future. In the current context of thriving cultural nationalism that attempts to hijack the forerunners of the Kerala renaissance and homogenise cultural history, a critical rehabilitation of Sahodaran’s subversive poetry and democratic cultural politics is vital. It is highly imperative to recover and rehabilitate Sahodaran’s cultural legacies in the context of the cultural nationalism prevailing today.

Changing culture and society through poetry

Sahodaran was a poet right from his childhood. His poetic sensibility flourished in his youth and he used his poetry to address vital questions in society. For Sahodaran, poetry was a powerful tool that could mould and mediate cultural realities and social consciousness. He wrote verses when he was unable to communicate with people at a deeper level through prose or rational dialogue. Poetry, for him, made the impossible, possible. For Sahodaran, poetry and verse communicated the incommunicable to people in an intimate and emotional way. He directly touched the collective unconscious and desires of the community at large. He believed in the transformative and affective power of verse. He evolved a unique poetic idiom, free of convention and clichés, its diction simple and clear. Sahodaran’s poetry was pro-people and pro-future. It is extremely readable and easy to understand, even today. He practiced a poetics of emancipation and change. He also renewed and revitalised the language and idioms of Malayalam.

His poetics was egalitarian and transformative. Poetry was politics and pedagogy for Sahodaran. As a rationalist orator and writer, he appealed to people’s rationalism. He complemented this rationalist appeal with an affective and emotional poetics. His poetics was charged with dynamism and diverse imagery that touched the human within the individual and the collective consciousness and unconscious of society. There are critics who have declared that Sahodaran’s verses are not pure poetry or artistic poetry. However, for Sahodaran, poetry and prose enhanced the world and made everything possible. He was for a humane, democratic and peaceful world where poetry and art flourish, in which everybody could create and innovate in their own ways.

Sahodaran’s poems were published in leading Malayalam journals of his time, such as Mitavadi and Vivekodayam. His verses were first anthologised and published by Sarada Book Depot, Thonnakkal, in 1934, and a second edition was published in 1945 (Sanu 1980). The cultural elites, however, kept silent about his works; Sahodaran was always aware of the silence of the threatened Brahmanical forces, which tried to obliterate his cultural interventions. But he was sure that his poetry would be recognised in the future for its innovation, micropolitics, and diversity both in theme and form. He was confident that his poetry was paving way for a new literary era in Malayalam (Sanu 1980). He focused on the clarity of ideas and affect rather than flowery, figurative, and complex language. He was also confident that his unique poetic idiom, marked by a simple and direct style, would stand the test of time. The openness, organic frankness, lucidity, and earthy tinge of Sahodaran’s poems still maintains dialogic relations with the reader and offers a range of possibilities for new and democratic polyphonic readings in the future.

Rationality and subjective emotional sensitivity

In the preface to his poems, Sahodaran clarifies that he is not worried about the canonisation of his verses, as it was driven by political idealism and a need to share democratic values. However, he also writes that his poems are the product of his emotions, aroused by intelligence, reason, and thought. He also states that the verses are powerful enough to generate similar emotions and wisdom in readers. He acknowledges that he composed these verses with the intention of touching the hearts of people and inspiring them. He makes it clear that his poetry is part of the Sahodaran movement, the rationalist movement, and the Buddhist movement in Kerala, which changed the contours of culture in prose and poetry—in writing and life at large (Ayyappan 2001).

Radical and subversive ideas and democratic idealism were integral to Sahodaran’s literary imagination and creativity. He expressed rational ideas and humanistic ideals through his subjective poetry. He transcended the boundaries of emotion and intellect through his unique poetic practice. Sahodaran’s writing breaks the genre stereotypes and binaries of poetry–prose, emotion–intellect, and creativity–critical consciousness. His work opens up a new praxis of writing marked by organic dynamism, plurality, and cultural difference. It is also a reflection of his democratic cultural politics, which emphasises multicultural diversity and inclusion (Sekher 2012:86). As he predicted, his poetry inspired and emotionally recharged contemporary and younger readers and revolutionaries. In his autobiography, A.K. Gopalan, the legendary communist leader of Kerala, recounts how he used the following lines by Sahodaran in public meetings to motivate Bahujans to engage in collective social action (Sanu 1980:421):

The Bahujans who nurture the wealth and welfare of the land

With their sweat and life blood

Struggle in dilapidated huts without food and clothing

The poor women who give birth on damp floor

They are not just one and two but millions we must remember. [i]

In the preface, Sahodaran mentions Asan’s appreciation of his poem, 'Dharma Ganam' (Song of Ethics), saying that it contained lines that would make any poet proud. When it was published again in a special issue of Mitavadi, Ulloor S. Parameswara Iyer, a leading poet of the time, wrote a letter to the editor saying that he liked the poem (Sanu 214). Narayana Guru once asked a student to read Sahodaran’s poem, Parivarthanam (Transformation), to him repeatedly. Sahodaran also mentions how C. Krishnan encouraged his poems on Buddhist themes. M.K. Sanu observes that these poems were published in a book because they were dearly valued by Sahodaran’s friends and followers—these poems are also historically important, as they inspired the young reading and thinking generation of Kerala in a radical time (423). In 1917, when Nanuguru wrote 'Daiva Dasakam' (Ten Verses on God), Sahodaran provided a counter-balance with his composition, 'Science Dasakam' (Ten Verses on Science, originally written in 1917) and Nanuguru opined that people could read 'Daiva Dasakam' and then 'Science Dasakam'.

Subversive and defiant poetics

Sahodaran’s young friend and critic, Kusum, wrote the introduction to the 1934 collection, appreciating the simplicity, pleasantness, and energy of Sahodaran’s poetry. He also acknowledges its directness, austerity, and brevity. Most importantly, Kusum identifies the revolutionary spirit and radical subversive power of Sahodaran’s verses, and rightly affirms that Sahodaran is the originator of revolutionary and subversive poetry in Kerala and India, with a keen sense of modern democratic values.

The anthology originally published in 1934 was re-published by Kerala Sahitya Akademi in 2001 containing 64 poems.[ii] The verses are classified into eight parts (Kandam) according to theme. The choice of eight parts invokes the symbolism of the Buddha’s Ashtanga Marga (The Eight-fold Path of the Buddha). The first section, called Dharma Kandam, deals with the importance of ethics and morality in human life and bears inter-textual references to the Tipitaka and the Tirukural (Ibid. 50). The second section, Raja Kandam, is on statecraft, governance, and politics. The third section, called Swathanthrya Kandam, is on freedom and its significance. Yukthi Kandam, the fourth section, is on the importance of rationalism in human life. Invoking the ‘Panchaseela’ (Five Precepts of Buddhism), the fifth section—Baudha Kandam—includes poems dealing with Buddhism. Kadha Kandam, the sixth section, presents narrative poems. The seventh section, Charama Kandam, includes poems concerning the demise of important personalities like Narayana Guru. The final section is Sangirna Kandam, which has poems on complex socio-cultural issues. The anthologisation and classification are done in the manner of ancient Tamil anthologies, and Buddhist lore in particular. In theme and form, Sahodaran’s poetry defies and critiques Brahmanical and Vedic Sanskritic models and styles.

Polyphonic and multilateral poetry

As his own poem 'Hybrid' testifies, he believed in the philosophy and praxis of hybridity and cultural mixing. Sahodaran’s oeuvre is diverse and plural. He deals with a range of subjects and concerns, from ethics to death, and rationalism to Buddhism. In terms of philosophical affiliation, he aligns himself with indigenous non-Vedic philosophies like Jainism, Ajivika philosophy, and Buddhism in identifying the plurality of reality and the polyphony of human life.

In all his works, he upholds Bahujan traditions and critiques Brahmanical internal imperial culture (Dharmateerthar 1942; Reghu 2008). He subverts the homogenisation of Advaita reductionism that reduces the world into Brahman/Atman (self) explores the liberal pluralism of Anityavada/Anatmavada (Hinavada) and Anekavada (Syadvada), as postulated by Buddhism and Jainism, respectively. Sahodaran stresses the importance of human life and material social justice in the true spirit of the Ajivaka tradition. He also extensively utilises insights from Semitic traditions in his work—his signature way of addressing readers as 'brothers' derives from the egalitarian and fraternal spirit of Sufi, Islamic, and Christian traditions. It must also be remembered that Nanuguru did a consecration called Sahodaryam Sarvatra (Fraternity Everywhere) in one of his shrine installations having more more artistic and symbolic significance than religious (Sekher 2016).

So, while identifying and resisting hegemonic Brahmanical symbology and inflences, Sahodaran incorporated insights from philosophies as diverse as Buddhism, Jainism, Ajivika philosophy, Charvaka-Lokayata traditions and Islam, Sufism, and Christianity. His epistemological, symbological and cosmological orientation was plural and polyphonic like his guru’s. As a poet and thinker, he rejected a reductionist and totalitarian view of history, society, and the world.

As we already saw Sahodaran had been deeply interested in language and poetry from a young age. He was equally or more interested in social and political issues. Sahodaran and his friends were against all sorts of social evils related to decadent and exploitative forms of religion, including violent and perverse forms of worship. He campaigned against animal sacrifice during Kodungallur (Muziris) Bharani festivities, where millions of roosters were killed every year. According to historians, the Kavu (shrine/place of worship) in Kodungallur was a Buddhist or Jain sacred grove shrine before the Brahmanical conquest, and the site of a destroyed Buddhist nunnery (Valath 2003). It is still called Kavu (sacred grove). In the 8th or 9th century, Hindu Brahmanical priests captured it by mobilising untouchable ignorant people and allowing drunken revelry to pollute the temple, following which they converted it into a Brahmanical Hindu temple. The ‘Kavu Theendal’ (defiling the shrine ceremony) is a ritualistic commemoration of this heinous and barbaric conquest—it serves as a symbolic reiteration of the power of the Brahminic Hindu hegemony and a warning and reminder to Buddhists, Jains, and other minor sects who contest it. Most of the monks were butchered or converted, and the nuns violently raped and annihilated in the violence aroused and legitimised by Hindu religious frenzy. The blood, sex, and phallic and carnal symbolism of Kavu Theendal repress this inhuman violence perpetuated by the perverted religion and priesthood that established untouchability, patriarchy, and pollution in South India.

No to killing and violence

Sahodaran, a Buddhist and a lifelong crusader against the Brahmanical hegemony, recounts the history of the Brahmanical invasion and Buddhist persecution in poems like 'Alariyute Munpil' (Before the Alari temple tree), 'Divaswapnam' (Day dream), 'Rani Sandesam' (Message to the Queen), 'Rajavinu Prathyaksha Pathram' (Open Letter to the King), and 'Bharanikku Pokalle' (O Don’t Go to the Bharani). Through his speeches and editorials, he tried to educate people about Kerala’s Buddhist and Jain past and how Brahmanical forces infiltrated, invaded, and erased the egalitarian culture epitomised in Sangam poetry. In Mathilakam, a few miles north of Kodungallur, Ilango Adigal, the great Tamil Jain sage, wrote Chilapatikaaram, the ancient Tamil epic that manifests the Sramana tradition of South India. Manimekhalai, the daughter of Madhavi and Kovalan in Chilapatikaaram, who is the heroine of Chataranar’s Buddhist epic, Manimekhalai, attended the Buddhist university at Vanchi near Matilakam. Ilango was the brother of Chenguttuvan, the Chera emperor, whose capital was Vanchi/Muziris or Kodungallur (Gopalakrishnan 2008; Valath 2003).

Sahodaran and his friends campaigned against Kavu Theendal and animal sacrifice. The annual Bharani festival at Kodungallur happens in the Malayalam month of Meenam (A summer month in local calendar) and on the day of Aswathy (a day in the local calendar denoted by a star). It draws many Avarna untouchable devotees to Kodungallur from all over Kerala (Kesavan 1990). Licentiousness and obnoxious drunken revelry is promoted during the festival. Bharani songs are full of violent inhuman obscenities and are perverted forms of subaltern relief under Savarna hegemony.

No to othering symbolic violence and narrative tropes

In the early 1920s, Sahodaran and friends led a procession in which they sang songs that discouraged this violent worship. Bharanikku Pokalle (O Don’t Go to the Bharani) was composed during this crucial cultural political juncture in Kerala history. They also had the moral support of the editor of Mitavadi, C. Krishnan. In the temple’s vicinity, the caste Hindu elites greeted them with sticks and stones. Sahodaran and friends were beaten—fortunately, a Muslim trader protected Sahodaran by giving him asylum in his shop when the latter’s life was in danger (Subramanyam 1976).

Though he had risked his life in the attempt to abolish animal sacrifice and drunken perversions at Kodungallur Bharani, Sahodaran was able to get the royal decree prohibiting ritualistic animal sacrifice. Elaborate print campaigns led to the successful abolishing and transformation of many social evils. He also composed a verse appealing to the subaltern not to go to Palani, another ancient shrine in present day Tamil Nadu—the seat of the ancient Dravidian god, Murugan—which still attracts many common folks. Sahodaran also discouraged Bahujans from sacrificing their life savings to make a pilgrimage to these hegemonic places of worship, monopolised and financially controlled by Brahmanical forces.

According to Sahodaran, popular Hindu gods like Murugan, Kannan, and Ayyappan were Mahayana Boddhisattvas until the Late Middle Ages. These Buddhist shrines were gradually taken over by Brahmanism by the 16th century.[iii]

Ethics as the perfection of love: The Dharma Kanda

The Dharma Kandam literally means the canto of ethics. The very first poem, 'Dharma Ganam', expresses a polyphonic and composite worldview. The poet proclaims that man has not completely unravelled the mysteries of the universe. An ethical way of living is desirable for humans and the world at large:

Do not be disheartened by pondering over

The mystery of the world - man has not seen it (29).

The poet’s idea of god corresponds with the notion of ethics, in a Buddhist sense. It (God as well as Ethics) is the light in every individual’s heart and the guiding spirit of all knowledge and experience. Love and compassion for others is the only the means to developing this light from within. Divinity is seen as service to others and embracing an ethical way of life. According to critics like M.K. Sanu, love is a synonym for ethics in Sahodaran’s vocabulary (424). In other words, human love for the whole cosmos makes an ethical life and world possible. This world is one of peaceful coexistence, tolerance, compassion, equity, and justice—a brave new world of love without violence and repression. Through his poetry, Sahodaran sketched the cultural geography of such a harmonic world. His poetry, through generations of readers and interpreters, has achieved this goals of transforming the socio-cultural terrain of Kerala in less than a century. Sahodaran’s love-ethics are capable of winning other worlds in the future (Sekher 2012).

In the poem, 'Dharma', he defines ethics as equal love, mercy, truth, and service towards everything. He also criticises the pagan religion (Hinduism) for suppressing and controlling such human instincts in manipulative ways for the purposes of the priestly hegemony. Religion cheated and subjugated people by claiming monopoly over the absolute. It divided people and made them fight amongst themselves. Sahodaran criticises religion for restricting the human spirit from free enquiry and expression. Religion checks the unlimited flights of human imagination, creativity, and rational enquiry—it curtails the freedom and autonomy of human thought and speech. Religion poses the greatest impediment to the progress of modern empirical and human sciences. Sahodaran considered religion, caste, and god the enemies of people and the root of all evils in society.

By claiming the monopoly

Over the unknown

Religions also split the people apart

And spread hatred among them (34).

We need an egalitarian and ethical way of life. Ethics is the asylum and resort—the only way forward for humanity. The section includes three poems; the last poem in the Dharma Kandam is 'Sama Bhavana' (Egalitarianism). Developing the spirit of equality is the only panacea for a divided and hierarchical world wrecked by religion and cultural elitism. It is also integral to the development of an ethical life. Love, ethics, and egalitarian spirit coexist and complement each other.

The sun shines for all, and the clouds rain on everybody. Equality blows like a wind on beings all over the world. Every human is born and must die. At least in birth, and in leaving life, we are all equal. The same theory of equality must guide us in human relations and social interactions. 'Sama Bhavana' salutes the egalitarian human mind that views everything as equal and supports fellow beings unconditionally. The poet reasserts the vitality of human love in making the world an equitable one. In a beautiful analogy, Sahodaran imagines love as a stream that springs from the bottom of the heart to quench the world’s thirst. Love is a river that makes the world fertile.

Hail to the equitable mind that quenches the thirst of the world

And makes it fertile with the river of love

That springs up always equally from the bottom of the heart... (36).

Politics and poetics: The Raja Kandam

Raja Kandam is the canto on politics and statecraft. Sahodaran was aware of the interrelation between writing, representation, and reality. He never ventured on flights of fantasy for their own sake. He tried to provoke society’s conscience against social and cultural decadence and the evils of the time. The five verses in Raja Kandam are pleas for human rights and justice, targeting the ruling monarchy. His poems composed in the early 1920s furiously argue for the democratisation of society and polity.

In 'An Open Letter to the King' he writes that the people who have been enlightened by the teachings of Sri Narayana Buddha are waking the king with due reverence. The comparison of Narayana Guru to the Buddha is meaningful and historic. Both sages have challenged Brahmanism and caste and have preached the importance of using non-violent means of resisting cultural hegemony. It is even more significant in terms of cultural history, as the Avarnas of Kerala are inheritors of the Sramana legacy of Buddhism and Jainism (Gopalakrishnan 2008; Sekher 2016). A close affinity and dialogue with Sri Lankan Buddhism could also be identified in Narayana Guru’s life and praxis. He visited Ceylon twice (in 1918 and 1926), like Ambedkar later did.

In the poem, Sahodaran appeals to the king to stop the barbarity at Kodungallur Kavu during the Bharani revelry. He urges the king to stop animal sacrifice and the drunken revelry that dehumanise the devotees and decay their moral fabric. To provide ethical strength and courage to the king, Sahodaran invokes the teachings of the Buddha and his own guru against violence and bloody rituals.

Let the enlightened one who conquered the whole world

Through preventing the killing of animals and beings

By showing his own throat to stop the slaughter of a lamb

Be your model and resort always and for all times (53).

The poet warns kings and queens that despotic rule around the world is giving way to democratic governance. Sahodaran upholds the importance of individual freedom and autonomy in modern society.

Freedom as the essence: The Swatanthrya Kandam

Poems on freedom and brotherhood are included in the section called Swatandrya Kandam. The first eight poems deal directly with liberty and equality. The last poem is a scathing critique of Gandhi and his submission to the Brahminic priesthood at the Kanyakumari temple. According to Sahodaran, liberty, equality, and brotherhood sprout from all-encompassing love. In 'Freedom', (1934) he writes:

We who suffer even without the freedom of movement

Should transform our grief into a force that gives freedom to all

We need to sever the organised religious bondages

...................................................

The human world gains greatness only through gaining freedom

Freedom is the cause of all advancement and the lack of it is doom (70).

According to Sahodaran, depressed classes have the moral right, ethical advantage, and historical agency to transform society. Sahodaran urges the subaltern to radically subvert power structures and hegemony from below. He motivates people to reform the social and cultural norms of society through the quest for freedom. The impediments to human freedom have been created through religion and traditional culture dominated by the orthodox elite.

Let the love that springs up in the heart spread out near and far

Freedom dawns itself in the mind that is cleansed by this great flow

The sun of freedom looks everywhere and at everything at the same time

----------------------------------

Courage and knowledge, imagination and fancy

Mercy and other human qualities of the heart

Arise when humanity gains liberty on earth.

So love, sacrifice everything for love and out of love (72).

Rationalism and poetics: The Yukti Kandam

The Yukti Kandam explores reason and rationality, which are the foundation of modernity. The poet critiques traditional culture and patriarchal priesthood for curbing progress. He urges young generations to explore the avenues that science and technology open up.

In a long narrative poem written using an ancient Kerala folk ballad form, 'Yuktikalam Onappattu' (Song of Onam for the Age of Reason), the poet proclaims that the human world can be free only when the state and governance institutions prioritise reason. Sahodaran rejects the hegemony of obscurantist texts. He also remarkably modifies and reforms conventional Sanskrit metrical and stanza forms for the new age and uses simpler and more lucid forms. He advances his critique of patriarchy and priesthood in poems like 'The Trickery of Priesthood'. The poem 'God-Man' is a unique work that remains relevant to the society we presently live, in which ‘spiritual wholesalers’ and ‘saintly sinners’ attract and exploit the middle classes and castes. The poet also expresses his musings on and dreams about the future through poems like 'Bhaavi' (Future). His appreciation of Darwin and the theory of evolution are articulated in 'Parinamam' (Evolution); old inequalities and injustices are minimised in a future where the human race embraces a truly democratic society without hierarchies. In 'The Age of Science', the poet salutes the liberating power of science:

I salute science that teaches us to enquire eternally

No matter how much we knew as knowledge is unlimited

I salute science that illuminates the whole world

The science that advances humanity and its welfare

I salute science without which there is only darkness (99).

His quest for knowledge and the new epistemological breakthroughs and paradigms made possible by modern science are visible in his dignified defence of science.

Enlightened poetry: The Buddha Kandam

Sahodaran was the first to compose a Buddha Canto in modern Kerala. The 14 exquisite compositions in the section develop Buddhist themes in the linguistic and cultural context of Kerala. The teachings of Buddha on life and enlightenment are uniquely rendered through simple and charming Malayalam poetry. The poems are also historically significant for their cultural role in the Neo-Buddhist movement led by Sahodaran and C. Krishnan, which intellectually and emotionally influenced a young generation of readers at the beginning of the 20th century.

Man is the saviour of man, no one else to save us

We are collectively comprehensive; I follow the way of the Buddha

I ensure self defense and become self-reliant without bothering others

I follow the way of the Buddha ...

I am in amity with everything, all are equal to me, I am free everywhere

I follow the way of the Buddha (125).

'The Way of the Buddha' presents the essence of Buddha’s teachings and its implications for life through simple and beautiful lines that enlighten the common reader. Poems like 'Day Dream' and 'The Temple Tree' trace the history of Buddhism in Kerala through gripping and cathartic narratives. Sahodaran’s narrative poems are the best in their genre in Malayalam. They create a fantastical world and convey a human interest story and theme in a very aesthetic and engaging way. But Sahodaran always keeps away from the pitfalls of nostalgia and romanticising the past.

He dealt with rationalism and historiography through poetry. In a sense, Sahodaran increased the scope of Malayalam poetry in expressing greater, wider, and more complex themes and concerns. Sahodaran widened the linguistic culture of Kerala through his cross-cultural, multi-dimensional, and multi-disciplinary writing that emphasises plurality and polyphony. History, society, polity, science, reason, philosophy, and many other subjects and disciplines coexist and cooperate in Sahodaran’s poetry as a composite metaphor for life.

Fictional and social narratives: The Katha Kandam

The nine long narrative poems in the Katha Kandam (Story Section) are fictional social narratives. Poems like 'Rosa' and 'Ahalya' celebrate the value of true love. 'Raga Vijayam' narrates the triumph of selfless love over human bondage. Sahodaran’s remarkable sense of character and context and his evocative style characterise these compositions. His reiterates the love–ethics motif in sustaining and seductive ways. Sahodaran never hesitates to draw attention to social inequality and historic exclusion in and through his poetry. He deconstructs the cultural imaginary of hegemony and elitism by invoking Sramana traditions and critiques.

A Chandal is not born and a Brahman is also not born

One becomes a Chandal or Brahman through life and actions (177).

In 'Chandal' (Subhuman Outcaste), the poet narrates an incident in Buddha’s life where the sage was abused as a Chandal by a Brahman while begging for food. The Buddha explains the implications of the word to the high priest. Buddha rejects the hereditary divine right theory of Brahmanism and upholds the importance of human ethics and action. Sahodaran continues his critical attack on Brahmanism and priesthood in 'The Rebirth of a Priest', where a dog appeals to the Raja to make a Brahman a priest, so that he becomes a dog in the next life. Sahodaran’s skill in writing satire and comic poetry is evident in this hilarious composition. However, his aim here is not to ridicule but to correct age-old social stigmas and corruption.

Sahodaran has also appropriated English verses for poetic rendering in Malayalam. 'The Vision of Palpu' is an adaptation of the famous English poem, 'Abu Ben Adam'. He uses the composition to pay homage to a great social leader, Palpu, who after experiencing caste discrimination in his hometown of Travancore—despite being the first medical graduate from the community—became a medical officer in Mysore and returned to organise his people under S.N.D.P. Yogam. Palpu was instrumental in the historic struggles of Ezhava and other backward communities for political power in Travancore in the early 20th century. He was the driving force behind the mass memorandum submitted to the monarchy, complaining against exclusions in education and public service—Ezhava Memorial (1896). This mass petition, signed by 13,107 community members, was the result of the Savarna betrayal experienced in an early memorandum called Malayalee Memorial (1891), which was actually a Nair Memorial in hindsight, as it excluded other downtrodden communities from its purview.

Compositions dealing with such political movements prove the social thrust and historical gravity of Sahodaran’s poetry. He also narrated the lives and struggles of a people, rather than representing a few lives and individuals in his poetry. Domestic, national, and regional histories are meaningfully and artistically juxtaposed in his hybrid poetry.

Life and its complexities: Charama and Sangirna Kandams

Charama means death and Sangirna means complex. The short section on death, the Charama Kandam, includes two poems—one on the demise of Narayana Guru and the other on the passing away of Lonan, a friend and social revolutionary. The lamenting tone and elegiac form make them striking and intimate. The respect and love for the dead fill the compositions in a very touching and emotional way This direct appeal and clarity of thought and expression are marked features of Sahodaran’s poetry.

The Sangirna Kandam or complex canto includes verses on various issues at various critical junctures in history. It includes poems written for the rational and inter-caste marriage movements. The section showcases the verses composed as part of the Sahodaran movement, for its various meetings and public campaigns. It includes poems like 'The Pulaya Slum', in which the poet depicts extreme alienation and exclusion. This is also one of the earliest depictions of the life of the marginalised in Malayalam poetry. Poems like 'Don’t Go to the Bharani O Brothers' and 'Don’t Go to the Palani' are also included in this canto. There are also poems on marriage and inter-caste marriage. The early editions contained the ninth canto—Misra Kandam (Hybrid Canto). However, this canto has been omitted from the Kerala Sahitya Akademi editions from 2001, edited by Puyapilli Thankappan. Earlier, poems like 'Egalitarianism' were included in the Hybrid Canto. Now it is in the Dharma Kandam. M.K. Sanu observes that Sahodaran composed poems like Sama Bhavana to replace the traditional Ram Bhajans (Devotional Songs on Rama) and chanting in Bahujan households (Sanu, 435). Sahodaran also composed verses and secular hymns to be sung in Bahujan houses on occasions of marriage and death.

Sahodaran’s work deals with serious historical and political issues in intimate ways. They voice the anxieties and struggles of the time and envision a more egalitarian and democratic future for Keralites and humankind in general. Sahodaran’s poetry also renewed and democratised the poetic idiom and Malayalam language in various novel ways. The poems kindled new sparks of revolution and resistance in the literary and cultural imagination of Malayali’s and initiated change in Kerala’s linguistic culture. Sahodaran’s poetic intervention was unprecedented and marks an important historic juncture in the growth and development of Malayalam literature and culture.

Notes

[i] All translations of Sahodaran are from Sekher 2012.

[ii] All the references of original poems here are from the collection originaly published in 1934 and re-published in 2001.

[iii] Even today, women are not allowed inside many famous temples like Sabarimala. Avarnas are facing threats, as priests and administrators of the Hindu temples, despite government efforts whereas their money and donations are welcome

References

Primary Texts

Ayyappan, K. 2001 (1934). Sahodaranayyappante Padyakrithikal. Thrissur: Kerala Sahitya Akademi.

Sanu, M.K. 1980. Sahodaran K. Ayyappan. Kottayam: D.C. Books.

Subramanyam, K.A. 1973. Sahodaran Ayyappan. Kochi: K.A.S. and Kerala Sahitya Akademi.

Secondary Texts

Ambedkar, B.R. 1986. Complete Works. Bombay: Government of Maharashtra.

———. 2002. The Essential Writings of B.R. Ambedkar. Ed. Valerian Rodriguez. New Delhi: Oxford UP.

Balakrishnan, P.K. 1986. Jativyavstitiyum Kerala Charithravum. Kottayam: National Book Stall.

———. ed. 2000 (1954). Narayanaguru. Thrissur: Kerala Sahitya Akademi.

———. 2006. Tipu Sultan. Kottayam: D.C. Books.

Bhaskaranunny, P. 2005. Keralam Irupatham Nuttandinte Arambhathil. Thrissur: Kerala Sahitya Akademi.

Dharmateertha, Swamy John. 1994 (1942). History of Hindu Imperialism. Chennai: Dalit Educational Society.

Gandhi, M.K. 1968. Varnasramadharma. Bombay: Navjivan.

Gopalakrishnan, P.K. 1998 (1974). Jainamatham Keralathil. Trivandrum: Prabhat.

———. Keralathinte Samskarika Charithram. 2008 (1974). Trivandrum: Kerala Language Institute.

Guru, Narayana. 2006. Complete Works. Trans. Muni Narayana Prasad. New Delhi: National Book Trust.

Kesavadev, P. 1999. Ethirpu. Trivandrum: Prabhat.

Kesavan, C. 1990. Jivita Samaram. Kottayam: N.B.S.

Kunhappa, Murkot. 1999 (1982). Sree Narayana Guru. New Delhi: N.B.T.

Muloor. 1998. Dharmapadam. Elavumthitta: Sarasakavi Muloor Memorial Committee.

Madhavan, E. 1934. Swatantra Samudayam. Trivandrum: Prabhat.

Moon, Vasant. 2009 (2002). Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar. New Delhi: N.B.T.

Narayanan, Aju. 2006. Keralathile Buddhamatha Parambaryam Nattarivukalilute. Thrissur: Current/Tapasam.

Omvedt, Gail. 2005. Buddhism in India: Challenging Brahmanism and Caste. New Delhi: Sage.

———. 2008 (2004). Ambedkar: Towards and Enlightened India. New Delhi: Penguin.

Pathmakumar, P.D. 2006. Jainadharmam Keralathil. Kozhikode: Mathrubhumi Books.

Phule, Jotiba. 1990. Samagra Vangmay. Bombay: Government of Maharashtra.

Reghu, J. 2008. Hindu Colonialisavum Desarashtravum. Kottayam: Subject & Language Press.

———. 2004. ‘Adhunika Keralavum Samudaya Rupavatkaranavum.’ Madhyamam Weekly. 7.7:28–31.

Sarkar, H. 1992 (1973). Monuments of Kerala. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

Sekher, Ajay. 2008. Representing the Margin: Caste and Gender in Indian Fiction. Delhi: Kalpaz/Gyan.

———. 2009. Samskaram, Prathinidhanam, Prathirodham: Samskara Rashtriyathilekkulla Kuripukal. Mavelikkara: Fabian.

———. 2012. Sahodaran Ayyappan: Towards a Democratic Future. Calicut: Other Books.

———. 2016. Nanuguruvinte Atmasahodaryavum Matetara Bahuswara Darsanavum. Trivandrum: Mythri Books.

———. ed. 2017. Kerala Navodhanam: Putu Vayanakal. Trivandrum: Raven.

Valath, V.V.K. 2006 (1991). Keralathile Sthala Charithrangal: Ernakulam Jilla. Thrissur: Kerala Sahitya Akademi.

———, 2003 (1981). Keralathile Sthala Charithrangal: Thrissur Jilla. Thrissur: Kerala Sahitya Akademi.