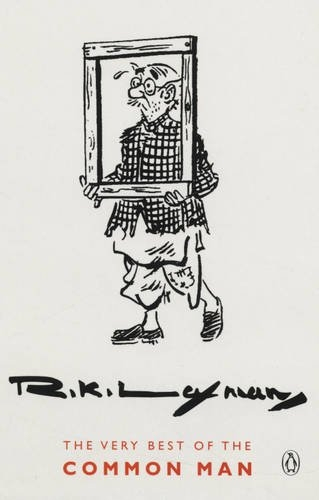

Undeniably India’s most famous cartoonist, R.K. Laxman’s talent lay in playing with irony, packing a punch in a deceptively light tone. We attempt to analyse 'what was it about his political cartoons that appealed to readers across six decades?’ (Photo courtesy: The Wire)

When the Sir JJ School of Arts in Mumbai turned down the young, aspiring artist Rasipuram Krishnaswami Iyer Laxman in the late 1930s, little did they know that a few decades down the line they would be erecting a memorial on their campus to honour him[1]. R.K. Laxman, as he is known popularly today, went on to have a prolific career as one of the greats of political cartooning in India.

A self-trained artist, whose art style wasn’t good enough for the premier art institute, became a household name by means of his daily cartoon strip, ‘You Said It’, in The Times of India. Besides apparent humour, what was it about his political cartoons that appealed to readers across six decades? Perhaps the answer lies within the frame and his inimitable style.

The Fine Line

The early decades of independent India saw the rise of several political cartoonists like Laxman who became watchmen of the country’s newly established democracy. Most of Laxman’s contemporaries—P.K.S. Kutty, Abu Abraham, O.V. Vijayan and Sudhir Dar—worked with other national newspapers. Like Laxman, they were largely self-trained and significantly influenced by cartoonists in the West. ‘Laxman and other cartoonists like Shankar Pillai, Ahmed, Bal Thackeray, B.V. Ramamurthy were all inspired by Sir David Low, (a) pioneer in world cartooning,’ says V.G. Narendra, managing trustee of the Indian Institute of Cartoonists, Bangalore.

‘Mahatma Gandhi Road’ - RK Laxman’s commentary on the change in Indian society

— Cartoons of India (@cartoonsofindia) April 11, 2018

#gandhi #india #mgroad pic.twitter.com/Z22iJ5PMXQ

Laxman’s linework, in particular, was significantly influenced by Low’s, a New Zealand-born cartoon and caricature artist, who lived and worked in the UK for many years. ‘Laxman was under the Low spell a lot more than even Kutty, who was clearly open to other global influences including Vicky (Victor Weisz),’ reiterates E.P. Unny, Chief Political Cartoonist, The Indian Express. The ‘classical measured brush stroke,’ as described by Unny, was a defining characteristic of Laxman’s draughtsmanship and Low’s influence. It contrasted with the uniform, neatly finished linework of some of his contemporaries like Dar. However, Laxman improvised a lot on the ‘Low mode’, added Unny. This is evident in the level of detailing in his drawings. While Low usually used bold lines, reserving details for emphasis within a frame, Laxman used details to draw out textures and set the mood of the scene. A balanced synergy of bold outlines, one-directional strokes and solid blacks are what Laxman used to capture the essence of the moment.

Also read | The Indian Cartoon: An Overview - by E.P. Unny

In his autobiography, The Tunnel of Time, Laxman mentions that he drew objects he saw outside the window of his room, from dry twigs to lizard-like creatures and crows in various postures.[2] It was this attention to everyday objects that made its way into his art by way of details.

Meaning Within (the Frame)

“The juxtaposition of incongruous elements is an essential element of storytelling in cartooning, and Laxman, like all masters, used it with much flourish,” says Unny, who is working on a title on Laxman for Niyogi Books. For instance, while commenting on the Budget, he shows the country’s poor—in rags—hidden behind a resplendent banner painted with a glorious sunrise and the word ‘BUDGET’ on it. This idyllic village scene on canvas is a far cry from the reality peeking out from ‘behind the scene’. Leaning towards realism as opposed to the caricature seen in Vijayan’s works, the vista could easily pass for everyday life. Nor does the scene possess aggressive overtones as visible in the works of Rajendra Puri, a cartoonist for The Statesman and the Hindustan Times during the 1950s and ’60s. In Unny’s words, ‘he (Laxman) packed his punch in a deceptively light tone. Endearing with the sting intact.’

Drawings of RK Laxman, just sublime. A deep understanding of India and our people. Read the captions underneath.. hilarious pic.twitter.com/3wl6vHA0IZ

— Arvind Ramanathan (@curiousraman) October 18, 2020

Text and Context

Besides the visual representation of real-life elements in his cartoons, Laxman’s use of text—content and placement—was integral to the transmission of its meaning. Oftentimes, the text was delivered as a dialogue or a nonchalant statement masquerading as a caption.

Related | In Conversation with E.P. Unny

In ‘The Rhetoric of the Image’, semiologist Roland Barthes talks about the presence of the linguistic message in every image and its two functions: anchorage and relay. While text used as anchorage shows the reader what to read (and what to omit); as in the case of a photograph with captions, relay’s (text) function becomes apparent in cartoons and comic strips where ‘text (most often a snatch of dialogue) and image stand in a complementary relationship’[3] to convey a unified message. Barthes further says that though both functions can coexist in one image, the dominance of the one or the other determines the interpretation of the image. In Laxman’s works, more often, text functions as relay, like where he shows a series of social evils that have led to the deaths of the persons crawling out from under the tomb, along with the line ‘buried decades ago’ seamlessly merging into the tombstone. The text by itself does not tell the reader what to make of the scene. It is only when seen in totality with the visual and other textual elements—like the caption in the left corner that says, ‘They keep coming out because they have political influence, I'm told’—is when one can glean the sarcasm intended. His usage of text contrasts with that of Abraham’s and Vijayan’s who used witty one-liners and captions to put their message across.

October 24th was R K Laxman's 99th birth anniversary !! Here's a small tribute to the legend by #Cartoonist #Alok to celebrate his centenary year #RKLaxman pic.twitter.com/EYQ3pgkx2w

— Surbhi (@surbhig_) October 25, 2020

An Iconic Representation: The Common Man

In ‘Cartooning Democracy: The’ Images of R.K. Laxman’, Dr Sushmita Chatterjee says, ‘the visual graphics (in Laxman’s cartoons) offer a wealth of details that are easily identifiable and mischievously personal in their Indian-ness.’[4] Laxman’s ‘Common Man’—a bespectacled, balding, dhoti and plaid jacket-clad, middle-aged man—was a testimony to this ‘Indian-ness’. Both Narendra and Unny agree that the character of the Common Man—an embodiment of every Indian man/woman—in cartooning is not unique to Laxman. However, what does make his representation inimitable, according to Unny, is his ‘silent, incidental presence’, taking in everything happening around him. He is always in the midst of action, watching the situation unfold, yet at the same time he remains in the margins.

This article was also published on The Wire.

Notes

[1] ‘School which rejected R.K. Laxman to house his memorial’, IANS, The Indian Express, 24 October 2015. Accessed 23 October 2020. https://indianexpress.com/article/trending/trending-in-india/school-which-rejected-r-k-laxman-to-house-his-memorial.

[2] Rajat Ghai, ‘R K Laxman and his love for common crow’, Down to Earth, 31 October 2018. Accessed 23 October 2020. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/coverage/india/r-k-laxman-and-his-love-for-common-crow-48379.

[3] Roland Barthes, Image Music Text; Essays Selected and Translated by Stephen Hath (Fontana Press, 1977), 41.

[4] Sushmita Chatterjee, ‘Cartooning Democracy: The Images of R. K. Laxman’, Political Science and Politics 40, no. 2 (April 2007): 303–06. Accessed on 20 October 2020, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20451949.