India has always had a sophisticated aesthetic philosophy and equally rich tradition of making everyday things beautiful. Creativity and culture permeate every aspect of day-to-day life in India. The collection at Raja Dinkar Kelkar Museum in Pune stands as testimony to this fact. Objects of everyday life connected with the manners and customs, beliefs and practices of the rural and urban population, along with other art objects of India mostly from the 18th and 19th centuries, are displayed in this museum.

This museum established in 1962 is a one-man effort of Padma Shri Dr D.G. Kelkar who, driven by an inner calling to collect the finest examples of human craftsmanship and preserve it for posterity, travelled across the country for over 60 years collecting whatever touched his heart and aesthetic vision. The museum holds over 20,000 objects of which 2,500 are on display.

Kaka, as Dr Kelkar was affectionately known, dedicated his collection to the memory of his only son Raja who tragically died an untimely death. Kaka was a man obsessed with art. He travelled to obscure villages and tribal settlements, to grand temples and humble huts, to forgotten attics and folk fairs—collecting, always collecting. He was a connoisseur who had an uncanny vision to spot the exotic in the everyday, for uncovering the diamonds under the dust. He was a man driven by an inner calling—to possess the finest examples of human craftsmanship, to throw light on the arts and crafts of India, and to leave for generations yet unborn, an insight into our rich, multi-faceted heritage.

Fig. 1: Sculpture of a deity

As one visits the museum the first thing that strikes is the impressive three-storeyed building recalling the historic Maratha period with galleries and rooms that gently lead to the treasure inside. On entering the building, an awesome collection of artistically decorated arches and windows set beautifully on the walls welcome the visitors. A magnificent collection of stone sculptures of deities lead the pathway. (fig.1)

Special attraction at the museum is the Vanita Kaksha (ladies chamber) devoted to the women of India. While observing the mind-boggling array of artefacts in this gallery, one is transcended to the bygone era where the average traditional routine of a lady started with waking up at dawn, followed by morning ablutions, anointing oil, scrubbing and bathing, braiding hair, applying perfumes, wearing lovely costumes and ornaments and beautifying the body with cosmetics and other adornments. Then commenced the household duties such as watering the sacred plant of tulsi, drawing rangoli at the entrance, hanging toranas on the doors and windows and during festivals, painting the walls with auspicious symbols. Then the puja of the household deities is performed in an altar, called by various names like devhara in Maharashtra (fig. 2). The pantheon of deities consists of gods and goddesses, often tutelary demi-gods and other sacred objects like the shankha (conch shell). The worship is performed by pouring an ablution of water on the god-figures using special vessels for the purpose, anointing the divinities with panchamrut consisting of milk, curd, honey, ghee and sugar; applying powders such as kumkum, haldi, abir, gulal; and showering the images with akshat (rice grains). Then the lamps filled with purified ghee or oil is lit and incense sticks or powders are burnt. Then offering of naivedya with sacred leaves such as bilva or tulsi along with flowers and fruits is made while chanting mantras and reciting prayers. During special occasions, musical instruments such as cymbals, the tanpura, harmonium, mridang, sitar and so on accompany the singing.

Fig. 2: Devahara (Domestic shrine)

The paraphernalia of these daily rituals includes many sacred vessels, containers, lamps, incense burners and aarti thalis. All these, although simple and humble, were beautifully and artistically executed, and they find a place in this beautiful gallery. Vajris or skin scrubbers, mirrors, combs, hair pins, kumkum and kohl containers, jewellery boxes, house shrines with idols of various deities along with worshipping apparatus, raised decorative pots for tulsi plant, are all present here.

Fig. 3: Vajris

The collection of more than a hundred varied brass pieces of vajris is unique because of the fineness of workmanship and the variety of themes, designs and conceptions. Almost all vajris are from south Maharashtra and Karnataka. An average vajri consists of two parts—the pedestal and the crowning figure or composition of figures. The bottom of the pedestal having a rough surface created by criss-cross incisions serves as the grip by which the tool is held. The pedestal of almost all vajris has perforated latticework. In addition to decorative compositions like the groups of peacocks, parrots, swans, there are scenes of hunting, wrestling, dancing, butter churning, and so on as crowning figures. (fig. 3)

Fig. 4: Torana

Also seen in this section is a typical Gujarati home recreated with traditional pillars, furniture, decorations, wall paintings and other utility items not only symbolising the warmth of a home but also putting the objects in their socio-cultural contexts. (fig. 4 and 5)

Fig. 5: Fan

The museum has a small and interesting collection of kitchen equipment and utensils that includes a copper oven, spice boxes, various coconut and vegetable slicers, nut-cutters, ghee and oil containers, metal plates, wooden spoon hangers and so on. These utilitarian objects rendered extraordinarily beautiful with ornate motifs of birds and animals, foliage and flowers, carved, engraved, breathe splendour into the mundane and purely functional.

Of these objects the most remarkable one is the copper oven from Rajasthan. The oven is roughly the shape of the traditional clay oven of the Indian villages, having two side walls and a back wall. In the front there are two semi-circular openings where firewood or coal is burnt. The hollow walls of the oven are constructed of double metal sheets, inside which water can be filled through holes on top. While cooking on the oven, the water inside the hollow walls starts to boil and thus keeps the already cooked food hot when the utensils containing food are kept on the side corners of the oven. The front walls of the oven are decorated with flower and bird motifs cut out from a brass sheet. This is an excellent example of traditional technology and innovation employed in utility implements. (fig. 6)

Fig. 6: Copper Oven

The best specimens of breathtaking Paithanis from Maharashtra, gorgeous Parsi garas, rich Banarasi brocades, colourful rabari embroidery garments from Kutch and Gujarat, kantha embroidered textiles from Bengal, kashida embroidery sarees from Karnataka, all find place in the gallery of textiles where these traditional Indian styles and motifs are preserved for posterity. (fig. 7)

Fig. 7: Paithani Sarees

The section on weapons and martial arts reveals a remarkable collection of swords, daggers, shields, spears, armours, goads, tiger claws and a rare collection of gun-powder boxes. All ornately decorated, engraved, studded or carved, each piece offers a beautiful insight into the weaponry of medieval times from Gujarat, Maharashtra and the southern parts of India.

The single largest collection of lamps in India is present in the Kelkar Museum. The ancient tradition of lighting oil lamps has a special significance in the Indian way of life. The lamp filled with ghee or oil is lit while reciting the following shloka: Shubhamkaroti kalyaanam aarogyam dhanasampadaha; shatrubuddhi vinashaya, deepajyotihnamostute—‘I salute the Supreme who is the light in the lamp that brings auspiciousness, prosperity, good health, abundance of wealth and the destruction of intellect’s enemy.’

Almost every Hindu ritual begins with the lighting of the lamp, an extension of the daily lamp-lighting ritual in the morning and evening that one can see in most Hindu households, beginning and ending the day with an invocation to light. The flame thus lit is called jyoti or deepak—representing Agni (god of fire) and Surya (sun god). It refers to not just the physical fire but symbolises the cosmic force or divine light which dispels darkness or ignorance. A glowing representation of ancient and modern lamps, domestic and religious lamps, metallic, wooden, stone and terracotta lamps, standing, swinging and rolling lamps, lamps with icons like Surya, Deep-Lakshmi, tribal lamps motifs of birds and beasts, in short, lamps in all conceivable shapes, designs and sizes can be found in one place in the gallery dedicated to lamps. (fig. 8 and 9)

Fig. 9: Hanging lamp

In India, it is common to find two types of images of deities—one made as per shastras or prescribed iconography and the other one having a rural or indigenous flavour coloured with local customs, beliefs and practices of everyday life. The museum has a beautiful collection of both the types. So, along with the standard specimens of the copper and brass images of a thirteenth century Shiva Nandishvara, a sixteenth century Lakshmi and Mahishasurmardini, a seventeenth century Nataraja and Venu Gopala and an eighteenth century Ganesha, there is also a hoard of small images from the rural part of society comprising of Ganesha and Kartikeya seated on the lap of Shiva where Kartikeya flaunts a Maratha cap or turban and several images of Balakrishna where baby Krishna is wearing either a Peshwa hat or an European turban. The casting of these images is marked by such characteristics as protruding eyes, simplified limb forms and details of features and ornamentation, extraneously applied as in terracotta.

Fig. 10: Carved Wooden Door

The intricately carved doorway and windows at the entrance of the museum is only a small indication of the magnificent ones in the collection. Variety of doors and arches with their own set of gods, goddesses and apsaras, majestic lions and other animals, painted archways, intricately carved panels, doors in wood and ivory, giant icons, welcome the viewer to the awe-inspiring world of artistic and architectural grandeur at the Kelkar Museum. In Indian culture, doors and thresholds have deep spiritual and symbolic meaning. Doorways are transitional spaces that allow positive energy to flow inwards while keeping negative energy at bay. Indians often decorate their front doors to attract good fortune. Objects and art that represent protection, blessing and abundance, like rangolis and toranas, the images of deities, purnaghata (vase of prosperity), lions and so on decorate the doorways. (fig.10 and 11)

Fig. 11: Carved wooden door

The carved windows of Gujarat and Rajasthan either have flaps or fixed screens with floral surface ornamentation or perforated tracery of wood. Often two small bracket figures of parrot, peacocks, horse heads or dolls are fixed as lintel projections.

In addition to architectural parts, the custom of using carved wooden chests called majus was very popular all over Gujarat and Rajasthan. The facades of these oblong chests normally made from sheesham were intricately carved. Often parrots, peacocks, or human figures were attached to it as brackets. Another sturdier chest with wheels at the bottom called petaaro was more common in Gujarat. The latter was usually encased in ornately embossed metal plaques. Other wooden objects of everyday life such as spice boxes, turban hangers, cradles, beds, swings, pitcher stands, lamps, opium boxes, opium grinders and hookah parts etc. were either carved or lathe-turned. The carved variety used shallow relief work of ornate motifs of flowers and birds, whereas the lathe-turned objects were usually painted or adorned with lac. Some fine examples of these can be found in the Raja Dinkar Kelkar Museum. (fig. 12)

Fig. 12: Palanquin

Another remarkable category of objects in the museum are six carved rolling carts for children to learn to stand up and walk a few steps while holding and leaning on the cart. These carts made of light square and triangular frames have two wheels at the back and one in front. The frames are beautifully carved or lathe-turned and embellished with floral and faunal motifs, and at least one of them depicts the figure of child Krishna sucking his finger.

Fig. 12: Nutcracker

No Indian feast is complete without tambul. Chewing of tambul meaning paan or betel leaf is a part of our age-old tradition. It is also a symbol of auspicious beginnings; usually used as a seal on alliances and invitations. It represents the deity in religious ritual. Paan is the inspiration behind verses, legends, paintings and popular songs. It is an aphrodisiac expounded in the Kamasutra. The Indian fondness and devotion to this tradition is eloquently revealed in the magnificent collection of over 150 paan boxes and lime containers along with nut-cutters, nut-holders and mortars collected from different parts of the country. (fig. 13 and 14)

Fig. 14: Nutcracker

This museum possesses a fairly large collection of spittoons made of bidri work originating from the Hyderabad area. Spittoons are essentially connected with ‘betel culture’ and their use must be as old as that of betel boxes and areca nutcrackers. Vatsyayana in his Kamasutra enumerates spittoon as one of the accessories to be kept near the bed. This practice of placing spittoons near or underneath the bed is depicted in many miniature paintings connected with romantic themes. The most common shape of an average Indian spittoon involves a circular bowl at the base and a large disc on top. The spittoon must have been an essential accessory of every Indian household because it was one of the utensils brought as a dowry by every bride.

The museum has one of the earliest and most extensive collections of the Chitrakathi folk paintings of Maharashtra. The Chitrakathi paintings, depicting the events from Ramayana like Ramavijay (the victory of Rama); ornate paintings on glass in the Tanjavur style; Pata or paintings on cloth from Rajasthan; Kalamkari art on cloth from Andhra Pradesh, miniatures in the Mughal style; the intricate and detailed one of its kind Chaitra-Gauri pata (painted panel on cloth) from Maharashtra; these and many other such works on leather, paper and parchment are displayed in the room devoted to the Indian paintings of medieval period. (fig. 15)

Fig. 15: Chitrakathi

The museum has a small collection of writing implements. This collection of inkwells and pen-cases is sheer poetry – even before it is written! Almost all in forged or cast brass, these ink-wells are both simple and ornate with animals and bird forms, and figures of gods. When not attached to the ink-well, the pen-cases are oblong or cylindrical boxes of metal, ivory, wood and papier mache with perforations, inlaid ivory, lacquered and painted motifs, in an array of workmanship that leaves one spellbound.

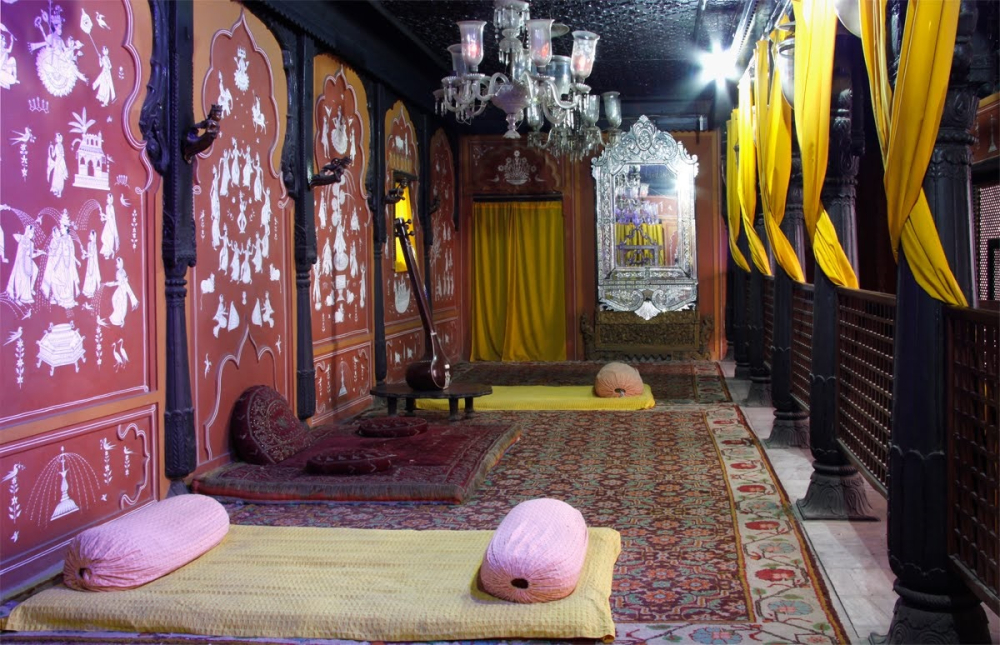

A corner of the museum which is of particular interest is the Mastani Mahal. The story of Mastani, the wife of Peshwa Baji Rao I, has recently become popular due to the Bollywood movie Bajirao Mastani. The relationship of Baji Rao and Mastani created a storm in the Peshwai which is why a separate house was allotted to her in Kothrud, Pune. The house is no more there, all that remains today is the painstakingly recreated corner of Mastani Mahal at Kelkar Museum. The luxurious setting, beautiful wall paintings, glittering chandeliers, ornately carved wooden ceiling, splendid lamps and mirror, innumerable musical instruments, along with the portrait paintings of Baji Rao and Mastani, all combine to recapture a fascinating romantic epoch in Indian history and evoke all the grandeur of Peshwa life. (fig. 16)

Fig. 16: Mastani Mahal

Other unusual artefacts worth mentioning are assortments of musical instruments in various innovative shapes, palanquins, carved woodwork, tinware, bowls, stones, hookahs, chess, Ganjifa cards, locks, miniature paintings, glass paintings, figurines, and artefacts made of bronzes and ivory. These are but a few samples of the full splendour of Kaka’s collection which lies in the storage. (fig. 17, 18 and 19)

Fig. 17: Maratha painting

. Fig18: Ganjifa Cards

Fig. 19: Board game

The collection of this museum demonstrates excellence in craftsmanship and conceptual innovation, be it in design or functionality. One can witness the marriage of practicality and aesthetics, of elite and popular traditions, which is the real essence of Indian art.

This kind of material is seldom on display in mainstream museums and little-known to the younger generation. The museum serves to introduce the visitors to the cultural value of these materials and broaden their perception of art in everyday objects.

Bibliography

Mulk Raj Anand (Ed.). 1978. Treasures of Everyday Art: Raja Dinkar Kelkar Museum. Vol XXXI, No. 3. Bombay: Marg Publications.

———2006. Raja Dinkar Kelkar Museum: A World of Wonders. Pune: Raja Dinkar Kelkar Museum.