Colonial and modern art at the Rashtrapati Bhavan

The painting collection of the Rashtrapati Bhavan has been built over the decades by successive viceregal and presidential incumbents in the house, shaped both by the leadership of the time and by the individuals responsible for maintaining the collection, decorating the house and overseeing its use. The collection thus represents the needs of the house of an important governmental and diplomatic figure—the viceroy or the president—at various times in India’s late colonial and independent history.

The Viceroy’s house was designed and built late in the British Raj, and as such the parameters and needs for the decoration of viceregal spaces already had a long history in Calcutta and other regional homes of the viceroy. The commissioning of the new house required many paintings to be copied or acquisitioned from other sites in the country. For instance the Long Drawing Room is embellished halfway down its length by two facing fireplaces, with two large landscape paintings set into the wall above each mantel. Both of these were executed by Oliver Hall (1869–1957), an English landscape painter, based on engravings by Jan van Ryne (1712–60). The paintings focus on the earliest phase of colonial presence in India, in Madras and Calcutta—a time when both cities were small settlements focused on their respective forts.

Portraiture: colonial and modern

With the construction of an entirely new house for the viceroy, paintings had to be commissioned, copies of existing portraits made and paintings from elsewhere around the empire moved to populate the walls of this new house. Lutyens in a letter dated February 1, 1929 bemoans the lack of royal portraiture available for the new house. His lament suggests that viceregal houses must include paintings of royal and aristocratic figures appropriate to local histories but also in line with other houses around the empire. As a result, the portraits in the Viceroy’s House were incredibly important and made by well-known portraitists.

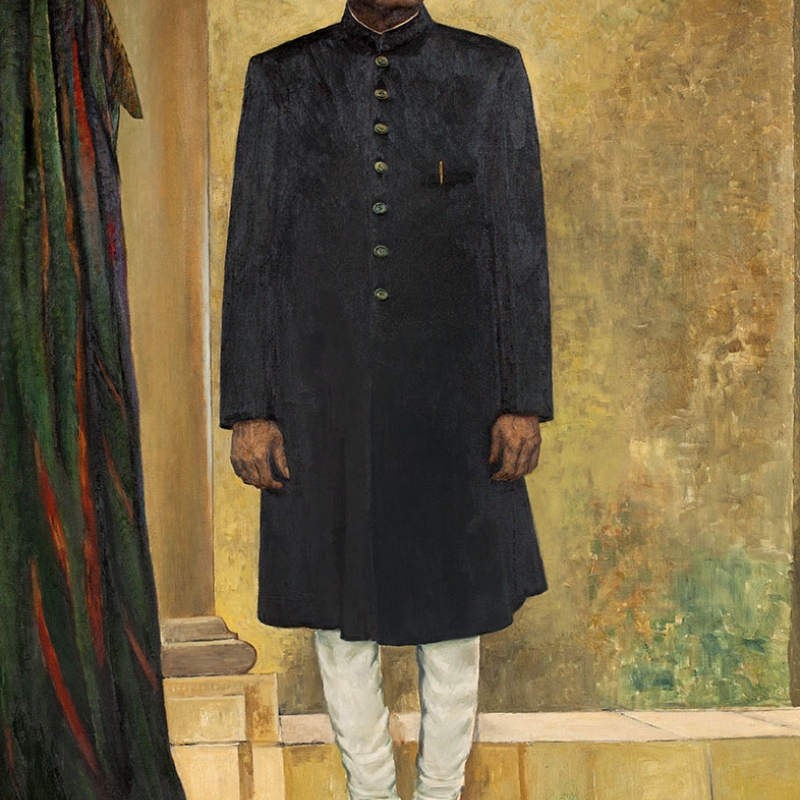

For imperial portraits, copies were required, and on the advice of W.E. Gladstone Solomon, the director of the Sir J.J. School of Art in Bombay, Lutyens agreed to stage a competition for two Indian artists to travel to London to complete the copies. Atul Bose (1898–1977) and J.A. Lalkaka (1884–1967) were selected from a shortlist of five artists, and completed several copies working in the Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace. In addition to copies, paintings moved to New Delhi from regional viceregal houses. Robert Hume’s portrait of the Marquess Wellesley and A.W. Devis’s (1762–1822) portrait of Warrren Hastings, like many other paintings in the collection, came from Calcutta.

In addition to paintings, the viceroy’s residence also commissioned portrait sculptures in marble: full-length figures such as Queen Mary by George Frampton (1860–1928) alongside busts such as Rosamund Ridley’s (1877–1947) portrait of Lord Chelmsford. Like the paintings, some were brought from other locations, and others such as the Ridley bust, were commissioned for the house. These sculptural and painted works largely remained in the collection of the house, even after Independence, despite several efforts to decommission them or to send them to the National Museum. At a time when public sculpture of colonial figures were removed from the capital, many of the works in the Rashtrapati Bhavan collection remained in place. The commissioning of both sculptural and painted portraits continued after Independence in 1947, slowly replacing the colonial portraiture in important diplomatic spaces. For presidential portraits, established artists were invited to execute the full-length paintings that now hang in the State Dining room, replacing earlier colonial portraits.

Select themes: princes, soldiers, landscapes and histories

Many changes have occurred over the course of the life of the house as its incumbents have changed, and as it shifted from a British colonial space to one showcasing independent India. Portraits of individual princes, paintings of types of Indian people, Indian and European landscapes and history paintings find a place within the painting collection and on the walls of the state and private rooms in the house. In addition to these genres, all of which would be expected in a viceregal or presidential setting, a group of large-scale copies of select Ajanta frescoes (c. fifth century AD) were also brought into the collection, now found in the morning room.

In the South Drawing room hang a set of paintings by Thomas Hickey (1741–1824). The figures are associated with the court of Tipu Sultan and the aftermath of Tipu’s defeat by the British at Seringapatam in 1799. The paintings include the surrender in the battle as well as that of Krishnaraja Wadiar [sic] III, who was placed on the Mysore throne by the British when he was only five years old. Other regional rulers such as Jung Bahadur Rana, prime minister of Nepal and eventually ruler, by the Welsh portraitist Thomas Brigstocke (1809–81) give the house a British-Indian presence rather than simply a British imperial one.

Landscapes also decorate the walls of the diplomatic house, sometimes serving largely as background decoration, as in the case of typical 18th-century views of the Welsh countryside. These types of landscapes offered picturesque backdrops of two sorts: the British examination of ostensibly untouched nature outside of English and Wales, and the colonial picturesque of decaying architectural edifices overgrown with vegetation and populated by colourful ‘natives’. The choice of these genres in the 1930s should be read as an antiquarian gesture drawn from 18th-century sensibilities.

Post-independence diplomatic collections

The Rashtrapati Bhavan benfited from the leadership of several artists as they built and maintained the collection. In the mid-1970s, the artist Sukumar Bose (1912–86) held the title of ‘Honorary Art Advisor’ to the president and alongside the then curator of the collection, Jogen Chowdhury (b. 1939), was one of the strongest voices against decommissioning both colonial and modern art from the presidential house. In all the paintings and sculptures now decorating the rooms in Rashtrapati Bhavan one can sense a long and engaged history. That most of the colonial era collection remained at the Rashtrapati Bhavan indicates the import of these works, even in a time when their subject matter might have been seen as running counter to the political needs of an independent, democratic India. The richness of their histories and the ways in which they continue to speak to us underscore the reason they remain such an important part of the Rashtrapati Bhavan.

References

Jaffrelot, Christopher. 2005. Dr Ambedkar and Untouchability: Fighting the Indian caste system. New York: Columbia University Press.

Mitter, Partha. 1994. Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 1850-1922: Occidental Orientalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.