Located about 60km from Dharmashala, away from busy trade and commerce routes, stands the single largest structure of excavated sandstone on a mountain ridge, a group of 19 rock-hewn temples. The temple complex, often referred to as the ‘Ellora of the North’, excavated on the single outcrop, is the only one found in the Himalayas. Only three other monolithic rock-cut temples may be mentioned—Mamallapuram (Mahabalipuram), Dhamnar in Rajasthan, and the Kailasha shrines in Ellora. However, while Dhamnar and Ellora are below the ground level, the Masrur complex is at a height of almost 2,500 ft. Also, Masrur is almost three times the size of its rivals.

The monolithic complex is excavated after almost scooping out two parallel blocks of sandstone rock from either side and making the complex a standalone structure. Styled in the nagara form of architecture, the temple complex is said to be a mature form of nagara-shikhara style—a more developed form from the plains pertaining to the end of 7th to the beginning of the 8th century. But these developments of higher form of temple excavation remained understudied and unknown to scholars due to their remote location high up on the mountains, away from ancient trade and travellers’ routes. A comparison of the same form and style can be made from the study of Baijnath Temple in the Kangra Valley—a detailed mention to which is found at the end of the article—excavated during early 13th century.

Discovery of the monolithic temples

The first traceable reference was in 1875 but it was not until 1913 when Henry Lee Shuttleworth (1915-16:1918:23), a civilian officer, visited the Himalayan temple and made notes on it. He reported his find to H. Hargreaves (1915-16:1918:39-48) of Archaeological Survey of India who published a written account as well as a useful and reliable plan of the ancient ruins. While Hargreaves was of the opinion that each shikara (spire) represented an individual temple, it was Shuttleworth who thought that the central shikhara was the main and the only temple, flanked by smaller temples all merging into the central one. Hargreaves (1915) laments the fact that in spite of having been recorded as early as 1875, little was done in the intervening forty years till the ASI report (1919) of 1915-16. He describes the ancient monument as un-surveyed and also mentions that no useful information on its unique character was recorded. By then, the local devotees, apart from nature, had already done some unintentional damage to the already ruined monolith. He immediately made recommendations for the removal of all ‘encroachments’ such as cowsheds, huts, and agricultural activities.

While talking about the discovery of Masrur rock-cut temples, we must mention Col. A.F.P Harcourt (1971:60-62), who first made an attempt to categorize temple architectural styles in Himachal Pradesh. Baron Charles Hugel (1845:9), who traversed through Kangra in 1835 mentions an ancient temple near Jwalamukhi which appeared to him to resemble rock shrines of Salsette and Ellora that he visited earlier. This could be the earliest, yet-unverified mention of the Masrur temples. And the fact that Hugel (8) found them similar to those of Ellora makes for a further study between these two temples of the earliest nagara architecture. Alexander Cunningham of Archaeological Survey of India(1882-83) travelled extensively and brought to light most of the temples, sculptures, and inscriptions for further study by James Fergusson and J. Ph. Vogel (1909).

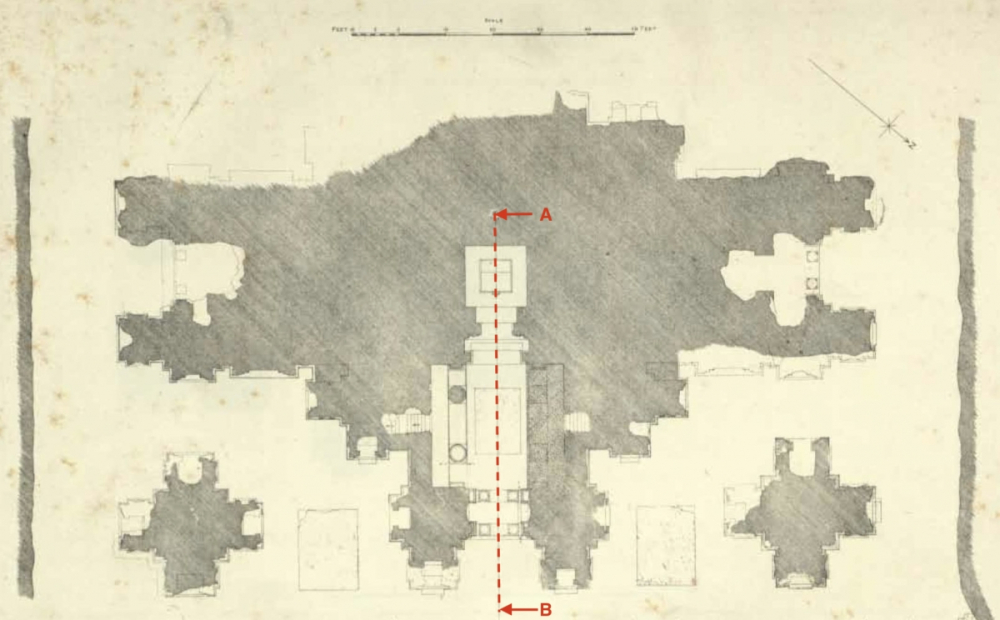

Fig. 1: Masrur Temple Ground Plan (after, Hargreaves 1915; (Source: https://archive.org/stream/in.gov.ignca.21849/21849#page/n114/mode/1up)

The earliest European visitor to Kangra was probably William Finch (1969:179-80) who in 1611 writes, ‘...Bordering to him is another great Rajaw, called Tulluck-Chand (Tilok Chand), whose chief city is Negercoat (Nagarkot, now Kangra)...in which city is a famous pagod called Je or Durga...'. Foster (294) mentions another traveller, Thomas Coryat whose travels around 1615 included the famous temple of Jawala Mukhi in Kangra. Coryat writes, ‘...Nagracutt; the chief citie so called, in which there is a chapel most richly set forth, both seeled and paved with plate of pure gold. ...In this province there is likewise another famous pilgrimage to a place called Jallamakae...dayly to be seen incessant eruptions of fire...’. But there is no mention of Masrur or any rock temple in the mountains.

So inaccessible and remote was this majestic complex that O.C. Handa (2008:125) writes,

‘...Until then, an arduous predator-infested wild track was the only access to this forlorn and melancholic relic of the early medieval period. Possibly for that reason it escaped the notice and consequent destruction in the hands of the iconoclastic hordes of the Kangra region. Thus, this monument continued to stand majestically aloof in the wilderness, unmindful of the political upheavals around it. The vagaries of nature also could not cause much harm to its original grandeur, except of the weathering of the softer parts of the rock. Even the devastating Kangra Earthquake of A.D. 1905 passed over it without a scratch on its monolithic solidity. The monument continued to languish in obscurity and consequential neglect up to 1875, when it was noted for the first time among the Objects of antiquarian interest in the Punjab and its dependencies, Lahore, 1875. However, it continued to be at the mercy of elements until 1912-13 CE, when the Archaeological Survey of India documented it for protection and conservation.’

Himalayan trade routes, state, and rulers

To know the origin of the monolith, one has to study the history of the sub-Himalayan region. The temple complex faces the Dhauladhar range in north-easterly direction almost along the course of the Beas river. Most of the ancient towns of the sub-Himalayan kingdoms were located between the valleys of the rivers Beas, Ravi, and Sutluj, known as Trigarta in ancient times comprising of kingdoms of Kangra, Chamba, Sirmur, Bushahar, and Kulu. These had important trade routes passing through them. These ancient routes were travelled by traders, merchants, artisans, and pilgrims. Some of these trade routes are still in use. This route was also traversed by Hiuen Tsang, who visited India during Harshavardhana’s reign in the early 7th century CE. The Beas Valley group of temples appear at key points along the ancient trade routes linking the plains of northern India with the trans-Himalayas. The Beas basin is in between Ravi in the west and the Sutluj in the east. The fertile valley provided an easy access to cross the lesser Himalayas, the Dhauladhars, to reach Tibet and central Asia.

It was earlier thought that mainstream Indian art reached the sub-Himalayan region late due to its remoteness but archaeological evidences show that ancient Kangra region had links with the great Mauryas, Kushanas, Guptas, and Harshavardhana, empires that rose and fell in northern India. The Mauryan Empire (4th to 2nd century BCE) extended its boundaries into present-day Himachal Pradesh. After the collapse of the Mauryan Empire many Indo-Greek kings ruled in Panjab and extended their territories to the western Himalayan provinces. The Kushanas ruled in the region before the Gupta dynasty came over and vast swathes of land came under their rule. It is possible that the basic style of temple architecture in the sub-Himalayan kingdoms took shape under the Gupta influence (Aryan 1994:12).

From the last quarter of the 5th century, the Gupta empire declined in the face of the Huns. Early in the 7th century, King Harshavardhana ascended the throne in Thaneswara (606 CE). After King Harsha’s death there were many small states who fought among themselves and it was not until 700 CE that the powerful king Yashovarman came to possess a vast empire with its capital in Kannauj. According to Kalhana’s Rajtarangini, Yashovarman allied with Kashmir’s king Lalitaditya Muktapida of the Karkota dynasty but the alliance did not survive for long. Though the political condition in north-west India during the eighth century is too obscure to establish an account of the hostilities between territories so vastly apart, territories of Jalandhara (present day Kangra) did come under the possession of the Kashmir king (Stein 1979: 89).

From 8th to 10th centuries, the powerful Pratiharas dominated north India. Until after 10th century, the western Himalayan kingdoms built alliances, regrouped, and broke again. From early 10th century, North India saw a series of invasions from Muslim invaders, finding itself under Mughal rule and as the Mughals weakened, in the hands of Katoch rulers. Inhabitants of the Jalandhara/Trigarta doab or Kangra, established themselves firmly in Kangra. While some historians credit the Katoch rulers for the Masrur temple complex, other scholars opine that their rule does not coincide with the estimated period of the Masrur construction. However, one is certain that local rulers did not commission the construction nor did the local artisans have the skill and know-how to build such massive structures. These may have been commissioned by wealthy traders with the help of migrant artisans from Kashmir (Handa 118-19).

Nagara style of architecture

Before going into the details of Nagara style of temple architecture of the Masrur complex, it is important to keep in mind that the simplest temple structure in India dating back to the Gupta period consisted of a simple garbhagriha (sanctum), with an attached pillar and porch and a flat and simple roof. Such simple, square, flat-roofed shrines are found in Aihole and Deoghar (Dey 2016). Gradually, the workmanship refined and artisans began to take more complex and intricate features and grandeur like the Masrur temples. This was the classical or the ‘golden age’. The types of temple architecture took different forms at around this time: the Nagara type prevailing in the northern part of India, between the Vindhyas and the Himalayas; Vesara between the Vindhyas and the Krishna; and Dravida, between Krishna and Kanyakumari.

It was the emperors of North India who first built the Nagara type of temples in Himachal when they ruled over this region. Later, the local rulers followed the trend and nagara style continued to evolve in the sub-Himalayan kingdoms. Masrur is the earliest, extant Nagara type of temple in Kangra. Therefore, it can be surmised that the earliest style did not evolve in the hills, rather were introduced in the late Gupta period. The Gupta style architecture with regional variationswas followed in the region. In the absence of any inscription at Masrur, it is difficult to date or ascertain any particular king or dynasty for its creation; whereas, in Baijnath temple, the inscriptions give useful information about the kings, patrons, and travellers who visited.

The characteristic features of the Nagara temples in Himachal are similar to those of Rajasthan, central India, Uttar Pradesh, and Odisha. These are comparatively small in size but have all the elements of the temples of North India. The square sanctum is preceded by pillared mandapa. The shrine consists of three components—the socle, the wall, and the shikhara. The temple is approached by a single doorway. The shikhara rises in multiple storeys marked by chaityas in some cases. Above the griva (neck), the shikhara is divided into three parts: amalaka, chandrika, and kalasha. The superstructure consists of three varieties: phamsana, latina and valabhi.

Among these, the latina type emerged in late 7th or early 8th century. Bold northern vedibandha (foundation block), ornate pilasters with articulate jangha (walls), niches on the bhadra, and heavy-shouldered rekha shikhara are the principal characteristics of this architectural style. Most of the stone temples in Himachal Pradesh—including Masrur—are part of this category, though Hargreaves would put it as Dravida. However, the merging of one style in another was not uncommon. Of the stone temples in North India, Masrur is the only rock-cut monolithic temple. Krishna Deva, former Director General, Archaeological Survey of India, made several explorations in the area. According to him, the Masrur monolith belongs to the latter half of 9th century Pratihara period. ‘...the rock-cut temple complex at Masrur (District Kangra), dating from the later half of the 9th century, is also a notable Pratihara monument of considerable artistic and architectural significance (Deva 1969:26-27).'

Extant ancient temples date back to the 8th century and represent Nagara style architecture tracing progression from the rock-cut temples of Masrur, Vishweshwarnath, Bajaura, and Baijnath (early 13th century). The vibrant facial expressions, lyrical figures as if they are in motion, combined with languid postures—female figures as well as male—talk about a generation of artists who not only knew the arts but the human anatomy too. Perhaps for this reason, the temple of Masrur stands as one of the most significant stone temples in the sub-Himalayan region. There is, however, a debate around whether these skilled artisans travelled as a guild and were commissioned to build the temple. Art historians opine that these were local artisans who imbibed the Gupta, post-Gupta, Pratihara, and Kashmiri styles—reason being the Guptas had left strong impressions on artistic and architectural traditions.

It is also of immense importance that the intense architectural activity during 6th-7th centuries not only signifies rich cultural heritage but also speak of political and economic stability and prosperity in the Himalayan kingdoms and a developed communication system among the guild. It can also be surmised that groups of artisans travelled from one kingdom to another. About two centuries later, the mandapa and the shikhara and the introduction of dressed-stone architecture was almost uniform in the region. The stone relief work and the design plan are similar to the Gupta style but more superior and advanced.

Fig. 2: Front view of Masrur Temple Complex, Kangra Valley, Himachal Pradesh

Commissioning the monolithic temple

Little is known of Yashovarman, during whose time it is said that the excavation of the Masrur temples took place, except that he reigned during the time of Lalitaditya, the king of Kashmir. However, it can be said that during his time there was political stability and appreciation of the arts as evidenced by the architectural splendour in Masrur which along with other stone temples of a similar type like Bajaura required considerable patronage from strong rulers and stable conditions. Whether these were commissioned by Yashovarman or the Katoch rulers or kings from Punjab (Dey 2015) is not fully known, but the beginning of the nagara style of architecture was evident.

Kalahana’s Rajatarangini mentions Raja Prithvi Chandra as having been at war with the Kashmiri kings towards the end of 9th century. It is possible that one of Prithvi Chandra’s ancestors may have commissioned this monolithic temple complex; though there is another theory: the ancestors of the Katoch rulers may have patronized the region and assigned the artisans the job of constructing this temple. Many of these kingdoms were feudatories of the Gupta kings and these vassal states—from Afghanistan to Bengal—followed similar architectural styles with variations.

General architecture of Masrur

Hargreaves (1915: 39-48) had put the temple in the Dravida style on account of the shikharas. However, L.S. Thakur (1996: 38-44) opines that the monolith belongs to the Nagara style as portions of the mandapa and the shrines flanking it were not fully exposed during Hargreaves’s time and the plan published then was not complete.

This rock-hewn art is about 170 ft in length and about 120 ft wide. The main temple faces east, flanked by smaller shrines on either side which rise up to the middle of the central shrine though most of these, particularly the shrines on the west, have collapsed. Above the main shrine, which is a massive and tall latina-shikhara and at level with the now-lost roof of the mandapa, the main spire and the shikharas (spires) mark the sanctum of each of the two smaller shrines. A similar pattern of these smaller shrines may have been at the back of the monument so that the main temple stood at the centre surrounded by smaller ones.

The mulaprasada faces east and is flanked by seven smaller shrines on either side—of these, two are at the level of the kantha (neck) of the central shrine and are called roof shrines. The graduated sukanasika projections on the four sides have three bhadramukhas arranged one on top of the other in receding succession. The amalaka capping is recognizable. The door is the largest in the sub-Himalayan region. It consists of five receding pedyas (jambs) and uttarangas (lintels). Beautiful floral designs—patrashakhas, padmashakhas, rupashakkhas—are carved on them. The lintels follow the same pattern. Lalat-bimba, the third and the main lintel has several figures with Shiva in the middle, an indication that this was a Shiva temple. Ganga and Jamuna appear on either side of the door. This appearance of the river goddesses is replicated almost in every stone temple in the Himachal region. The Kangra Fort has a dwar with the two goddesses flanking the gateway to the fort. There were four massive pillars supporting the missing mandapa roof. The bases probably hewn from living rock. A portion of the shaft of the one on the right is still standing. The square bases of the pillars are profusely decorated.

The receding flanks of the shikharas are carved in horse-hoof patterns on which are successive bhadramukhas carved within a medallion with the crowned heads of trimurti or Shiva Maheshwara. Following the belief that Mount Meru, or Meru Parvat, is the ultimate cosmological abode of all gods and goddesses, it was auspicious to build a temple atop a mountain as the ultimate abode of god. Also, because temples were made offerings of jewellery and other such valuables, it was considered safe to build them at a higher altitudeas a measure against plunderers.

Fig. 3: Śikhara, Main temple, Masrur

The blueprint

The complex has 19 shrines. Apart from the mandapa (main) shrine, there are 16 subsidiary shrines—two flanking the mandapa shrine, the corner shrines, angle shrines, oblong shrines—and two more on the roof top. There are also shrines not part of this group, yet carved out of the same rock—these are two cruciform or free-standing shrines on either side. The south corner cruciform shrine is in a preserved state. The spire of the north one has fallen. The better preserved, rather, the least damaged east side facing the Dhauladhars, is the main temple, known locally as thakurdwara, abode of Vishnu. The religion may have spread here later. This seems to be the only hollowed-out pillared structure. The ceiling of the antarala (ante-chamber) is an intricately-carved open lotus pattern, surprisingly undamaged. The remains of the four supporting giant pillars with exquisitely carved square bases still standing at the entrance ofthe mandapa seem to be at the same point where these were sculpted. The inner shrine, the main temple, the courtyard, and the outer porch are all constructed in square form whose walls are plain in contrast. The sanctum has three regularly worshipped deities—Ram, Lakshman and Sita in black stone. These are of recent origin and worshipped by people who reside in the nearby village of Masrur.

Fig. 4: Maṇḍapa pillar, Main temple, Masrur

The temple of Masrur is oriented towards east by north-east as the sun shines, facing the Dhauladhar range. The rising sun was considered auspicious as the first rays of the sun illuminated the idol. The nucleus of the complex is a large east-facing Shiva temple enclosed by seven subsidiary shrines.

On the extremities of the longer sides are two medium-sized temples, each facing the transverse direction surmounted by four satellite shrines. The plan of the temple sanctum sanctorum (garbhagriha) is square. The doorway to the garbhagriha has five panels embellished with scrolls, diamonds, ornamented pilasters, ganas, and garland designs. The lintel on the doorway has miniature Ganesha, Kartikeya, and Shiva. The ceiling of the antaralais a carved lotus form surrounded by diamonds and smaller lotuses.

Fig. 5: Lotus petal ceiling, Sanctum, Main temple, Masrur

The roof of the mandapa is missing. The general condition of the collapsed roof which was almost a foot and a half thick is clearly visible from the other side of the tank. There is a stairway shrine winding up, entered through framed doorways, each, on either side of the mandapa, leading to the roof of the main shrine, to the central shikhara. The stairway to the right side of the portico is completely ruined and cannot be explored. There could be four mandapas with entrances and lesser shikharas for each mandapa. These are the monolithic mini shrines flanking the main shikhara. These are in the latina-shikhara type. In the eastern side of the temple complex that has survived, there are two sub-shrines.The shikharas are carved in the chaitya window motif. The chaitya motif may have been a Buddhist affiliation seen in early Buddhist caves. Perhaps this was the reason why Baron Charles Hugel (1845) found similarities with Ellora and Salsette mentioned above.

Each of the shikharas has three successive receding trefoil pediments—each bearing a medallion and a human face—stepped pyramidal horizontal tiers, diminishing in size as it rises up. The shikharas, base mouldings, and relief work on the walls are similar in all the shrines; the amalaka and the kalasha portions are lost. According to Hargreaves’s explanations, there might have been a plan to have a fourth entrance, towards the west. The unfinished entry on the north-by-west side has a gaping hole in place of the doorway, clearly stating the intention of the planner to have an entrance on thatside. However, the false doorways towards east and south might mean that it was left unfinished intentionally. The free-standing monolithic shrine towards the south is the most preserved of all the shrines. The 16-faced spire of this shrine with rectangular barrel-vaulted gateway also has the most elegantly carved gods and goddesses and is in the most preserved state. Shiva seated on Nandi, and Kubera are still in a relatively preserved state.

The jambs and the lintels of the angle shrines in the eastern niche are profusely carved. The roofs of the angle shrines on the north side have tumbled down. Whatever little is preserved of the architecture is due to the dry, hilly climate which may have helped in slowing down the process of disintegration even after so many centuries. Surprisingly, the sculptures in Masrur have nothing in common with the rest of Himachal. It is unique in style and idiom.

The four shrines excavated on the four corners of the main shrine have richly decorated and carved lintels and doorjambs but not been excavated inside as if deliberately left so—an incompleteness, common occurrence for rock-cut temples. There may be other reasons for the unexcavated doorways, that of lack of patronage, political conditions, and sudden exodus and various other reasons. There must have been an ambitious project to make this a mighty and eternal monument of immeasurable strength but the work achieved fell short of that ambition and it remained unfinished.

Fig. 6: Unfinished excavation, Entry on the North, Masrur

Fig. 7: Doorway marked with five śākhas. From outside to inside - purna-ghata and foliage band, another

foliage band, bands with divine and semi-divine figurines and two uncarved śākhas.

There is a tank in front of the temple, almost as long and probably as ancient.

Mapping the surviving iconography

The base mouldings (vedibandha): The miniature shrines are crowned by a phamsana—tiered, pyramidal shaped shikhara and a moulded basement (adhisthana). The base mouldings are carved richly with kalasha embellished with foliated scrollwork. The base mouldings are similar in all the shrines. The Baijnath Temple has pronounced vedibandha with gods such as Surya in the bhadra niche.

Fig. 8: Unfinished temple adhiṣthāna, Masrur

Roof of the mandapa and the stairway shrines: Similar to Masrur the early 13th century Baijnath Temple also has mandapas, and the roofs over these are still intact. The roof of the Masrur mandapa is intricately carved in a rich lotus pattern with half-lotuses around the central lotus. The sides are carved in diamond patterns. The side walls are roughly hewn, as if waiting to be finished. The stairway towards the left of the main shrine spiralling upward to the rooftop shrines has exquisitely carved doorways. The lintels have patralata designs and are recessed into three successive shakhas. If one climbs to the top through the still intact stairs on the left, one can see the sub-shrines from close, with their rich relief work. These have wonderful and intricate vedibandhas with mini-shikharas with intricately-designed pediments. The shikhara on the left is more or less intact along with its amalaka. Details of dwarshakha can be discerned from the unexcavated yet complete dwar of the corner shrine.

Fig. 9: Staircase view, Main temple, Masrur

The jangha or the walls rise straight up vertically and the shikhara above thiscarves inwards as it rises. Originally, it must have been no less than 80ft in height. The bhadra or the central portion has a sukanasa—a circular medallion and the trimurti or three-crowned heads of Shiva. The bhadramukha that is embellished in the north corner shrine that is still intact has sharp relief and the faces of the trimurti are distinctly discernible. The central face of Shiva faces the front while the other two face away to its right and left. The roof shrines, as mentioned earlier, standing on either side of the main shrine, are complete shrines but have no cella below.

The pillar in the mandapa in front of the thakurdwarahas asquare base with diamond-shaped designs engraved on it and finely-engraved patterns of floral forms on the cushion mouldings above it with ring mouldings on top of the cushion. The pilaster flanking the garbhagriha has ghata-pallava carvings—a rich foliage pattern that is also found elsewhere on the shrine walls. The finely carved foliage-patterned ghata or pots that are found engraved on walls, shikharas, columns, and capitals were also found during the Gupta period, when it was a symbol of prosperity and fertility. The capital of the shaft is missing.

Doorways and recessed lintels: The doorway to the main temple is a fine example of an ornate type of portal. It has five elaborately-carved recessed panels embellished with carved foliage details or patravallis and diamond patterns sunk between detailed framework of pilasters. On the lalatbimba, Shiva sits in the middle with Vishnu, Indra, Ganesha, Skanda, and Durga. Five ganas hold a crown over Shiva’s head. Five shaktis are depicted over the doorway of the angle shrine at the south-east corner. On the lintel of the east porch of the cruciform shrine are seven deities and Shiva is atthe centre. The lintel of the north porch of the cruciform shrine depicts five seated female deities. Apsaras and vidyadharas (flying angels) offering garlands are found on the eastern shrine. The lintel of the eastern sub-shrine,which is a block (there is no cella inside), is magnificently adorned with vidyadharas (flying angels), apsaras, ganas, mithunas, etc. There are deities that are at times difficult to ascertain. The worship and depiction of saptamatrikas, or seven mothers, is predominant in the region. They feature prominently on the lintel of the doorway of the thakurdwara, alternating with divine figures.

While some figures and images have survived through the centuries some are almost blunted by erosion and, therefore, partly unrecognisable. This is due to the unevenness of the mountain rock. There are images of Shiva, Indra, Surya, and Vishnu in the niches of the eastern shrine. A three-headed figure that is damaged is found in one of the corner panes. A makara is recognised beneath an image of Varuna (Meister 2009). The most striking image that has caught the attention of all is the figure of a couple in the eastern shrine, with the man’s arm resting leisurely across the woman’s shoulders.

References

------, 2015, ‘Majestic Masrur’, Frontline, online at http://www.frontline.in/arts-and-culture/heritage/majestic-masrur/article6756691.ece

Deva Krishna, 1969, Temples of North India, National Book Trust, New Delhi.

Archaeological Survey of India, 1919, Annual Report 1915-16, John Marshall ed. 2002.

——‘Antiquities of Chamba State’, Annual Report 1909-10.

Cunningham, Alexander, Archaeological Survey Reports, Vol. XIV, 1882 and Vol. XXI, 1885.

Foster, William (ed.). 1968. Early Travels in India: 1583-1619 (reprint). New Delhi: S. Chand & Co.

Handa, O.C. 2008. Panorama of Himalayan Architecture, Vol. 1: Temples. New Delhi: Indus Publishing Company.

Harcourt, A.F.P. 1971. The Himalayan Districts of Kooloo, Lahoul and Spiti (reprint). New Delhi: Vivek Publications.

Hargreaves, H. 1915. ‘The Monolithic Temples of Masrur,’ ASIAR.

Hugel, Baron Charles. 1845. Travels in Kashmir and the Panjab: Containing a Particular Account of the Government and Character of the Sikhs. J. Petheram: London.

Meister, Michael W. 2009. ‘Mapping Masrur’s Iconography’, Prajnadhara: Essays on Asian Art, History, Epigraphy and Culture in Honour of Gouriswar Bhattacharya. Edited by Gerd J.R. Mevissen and Arundhati Banerji. New Delhi: Kaveri Books.

Shuttleworth, H.L. 1915. ‘Note on the Rock-hewn Vaishnava temple at Masrur, Dehra tehsil, Kangra District, Punjab’ in Indian Antiquary, 44.

Stein, M.A. 1979. Kalhana’s Rajtarangini: A Chronicle of the Kings of Kasmir, Vol. I. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

Thakur, L.S. 1996. The Architectural Heritage of Himachal Pradesh: Origin and Development of Temple Styles. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal.

Vogel, J. Ph. 1909-10. Annual Report 1909-10. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

Bibliography

Aryan, Subhashini. Himadri Temples (A.D. 700-1300). Shimla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study, 1994.

Singh, A.K., Shuchita Sharma. Temple Architecture of the Western Himalayas: Ravi and Beas Valley. Delhi: Sundeep Prakashan, 2008.