In 1987, Merchant Ivory Productions, then an established name in the international film fraternity, embarked on their film adaptation of John Masters’ The Deceivers (1952). The project was ambitious, a swashbuckling epic closer in tone to Indiana Jones than A Passage to India, boasting a pre-James-Bond-era Pierce Brosnan in the lead. The film came up against peculiar obstacles that would be familiar to many at present: the crew was reportedly harassed by the local mafia following their refusal to enter into any transactions with them. The controversy quickly took political shape, with the crew accused of shooting an instance of sati. Matters escalated fast, and the producer, Ismail Merchant, was arrested on the charges of misrepresenting Hindu culture. Unfazed, he dismissed the charges, claiming that they had been concocted by a local businessman who was miffed at being cut out of the production. Merely a blip in the long and storied career of Merchant Ivory, the story of the making of The Deceivers serves almost as a template for the maelstrom of issues their films often found themselves at the centre of. Known for their languidly paced British heritage cinema, they were lauded and critiqued in equal measure for their attempts to depict onscreen complex transcultural negotiations marked by concerns of identity and capital.

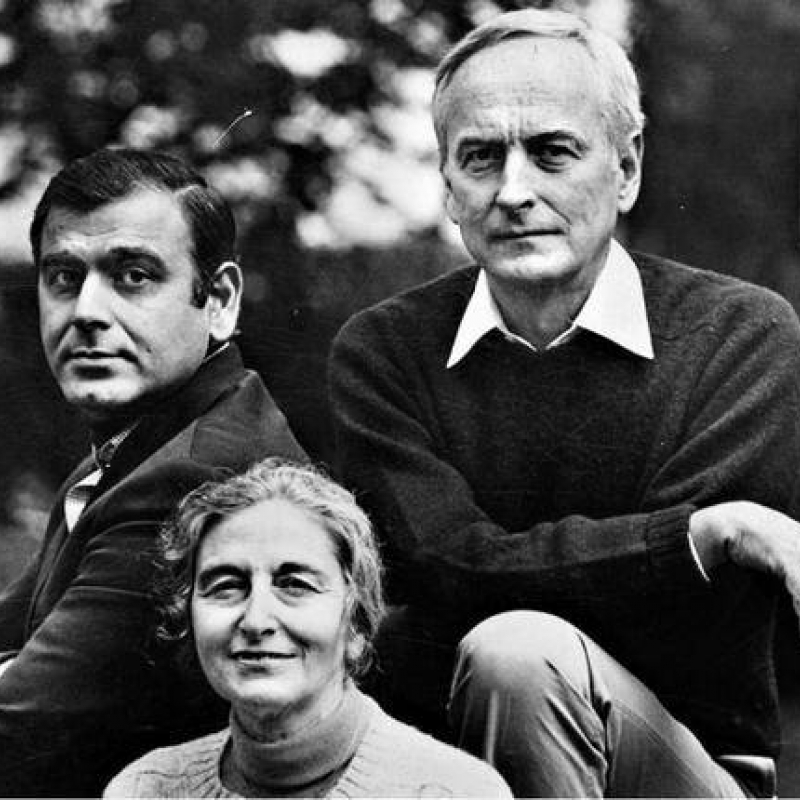

Formed roughly in 1961, Merchant Ivory Productions came into being around the triumvirate of James Ivory, Ismail Merchant and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. Ismail Merchant and James Ivory met for the first time at a coffee shop in New York, and Jhabvala would later join the duo when they visited India. The fateful circumstances under which a filmmaker from California, a Hindi film enthusiast from Bombay, and a literature student from Germany came together for their long, fruitful collaboration is a fascinating history to trace.

The Crossing of the Ways: How Merchant, Ivory and Jhabvala Met

Born in California, James Ivory studied fine arts at the University of Oregon before he joined the University of Southern California. There, he caught his first glimpse of India in Jean Renoir’s The River (1951). A landmark film for many reasons, The River also facilitated the first meeting between Satyajit Ray and the would-be cinematographer Subrata Mitra, who would go on to form the team behind Pather Panchali (1955). Soon after his time at USC, James Ivory was drafted into the army in 1952, and stationed in Germany for two years. His interest in the arts unabated, he made a short documentary on Venetian paintings titled Venice: Themes and Variations, released in 1957. When he encountered some miniature paintings from India, he impulsively decided to work on Indian painting for his next project. Since the paintings he wanted to work with were housed in American collections, he did not visit India for this documentary. Around the same time, he watched Pather Panchali, which proved to be a transformative experience for him. His completed film on Indian paintings, The Sword and The Flute (1959) caught the attention of the Asiatic Society, and Ivory was commissioned to make a film on Delhi. Ivory, thus, travelled to India for the first time to make The Delhi Way, a journey that would bring him to meet Ismail Merchant.

Ismail Merchant, the producer of the duo, was born on the other side of the world, in Bombay, in 1936, to Hazra and Noor Mohamed Rehman. His father, a leader in the Muslim League, refused to migrate to Pakistan after the Partition. Merchant studied at St. Xavier’s College in Bombay before he left for New York University. Unlike Ivory, whose interests and training concentrated on art documentaries, Merchant was deeply fascinated with the Hindi film industry and was even a friend of the actress Nimmi. Even before their friendship blossomed, a young Merchant would listen starry-eyed to stories of Jaddan Bai and Wahidan Bai from aristocratic friends of the family. He accompanied Nimmi to the premiere of Barsaat (1949), and remained a frequent visitor to her house in Marine Drive. Despite Nimmi’s urging for him to become an actor, Merchant had made up his mind to become a filmmaker. He was also deeply intrigued by the American way of life, and New York opened new vistas for him, letting him fully commit to a life steeped in culture and the arts. While there, he started working at an advertising agency as well as some television programmes. In 1961, he made the short film The Creation of Woman with Bhaskar Roy Chowdhury. On its release, the acclaimed film was screened at Cannes and received a nomination for an Academy Award. He had been living in Los Angeles for a year when he stopped in New York en route to Cannes, having received an invitation to attend a screening of The Sword and The Flute. He met James Ivory at the screening, who, in a transnational crisscross of fortunes, had just returned from India after making The Delhi Way. The two struck up a friendship and before long, Merchant expressed his desire to make a film in India.

Eager to help, Ivory introduced Merchant to the American anthropologist Gitel Steed. At the time, Steed was hoping to make a quasi-documentary film set in India. She had already spoken to the director Sydney Myers to helm the film. Ivory volunteered to photograph the project while Merchant took on the responsibility of production. For this project, Ivory visited India a second time, where he met Shashi Kapoor, Leela Naidu and Durga Khote, all of whom were to star in the film. Steed’s idea never came to fruition, but the seeds of Merchant Ivory’s first film in India had taken root. One of Merchant’s old ideas—to adapt Jhabvala’s novel, The Householder (1960), for the screen—came to the fore, and the two decided to journey to Delhi to meet the author.

Though Jhabvala was a resident of Delhi by the time Merchant and Ivory came calling, the journey that had led her there was a long one. Born in 1927 in Cologne in a German Jewish family, she lived through the horrors of the Nazi regime and saw her father arrested on suspicion of being a communist. The family finally escaped to Britain in 1939, and she found refuge in English literature, joining Queen Mary College to graduate with a Masters in Literature in 1951. She met Cyrus Jhabvala during this time, and the couple shifted to India after their marriage. A prolific writer, she had already written two novels before The Householder was published.

Merchant Ivory’s adaptation of Jhabvala’s novel, which would set the template for the production house’s idiosyncratic style, came at a fortuitous time. Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali, Aparajito (1956) and Apur Sansar (1957) had received widespread acclaim in the West. His cinema, tinged with neorealism and defined by its patient attention to psychological studies of character, would leave a lasting imprint on future Merchant Ivory productions. While the French New Wave’s more authorial and disruptive style was in full swing already, international film circuits were still open to Ray’s gentler lyrical realism. Ray himself would become a mentor figure to the filmmaking duo, even composing the music for their first two films—The Householder (1963) and Shakespeare Wallah (1965). Ray’s crew members, Bansi Chandragupta and Subrata Mitra, also worked on multiple Merchant Ivory productions. In Merchant Ivory’s frequent meetings with Ray, he would advise them on storytelling and cinematic strategies. Their influences did not remain limited to Ray, however. The two cinephile-turned-filmmakers were also deeply affected by the works of Ingmar Bergman, Akira Kurosawa, Carl Dreyer, Federico Fellini and Vittorio De Sica.

In addition to this wide sphere of influences, Ivory, Jhabvala and Merchant would bring to their films an emotional charge entirely peculiar to them. Ivory’s first visit to India raised complex emotions in him, and he strived to bring these to the surface of the films he made. An intimate observer of India’s post-Independence struggles by way of his associations with Merchant, Jhabvala, Shashi Kapoor and the Kendals, he was also acutely aware of his gaze being that of an outsider, engendering knotty contradictions that found their way into his works. Jhabvala felt similarly—a feeling of always being on the outside, looking in, despite having lived in India for 24 years. The many cultural intersections between the three would come to bestow a narrative ambiguity to their films. These ambiguities were wholeheartedly embraced in their lives as well: Merchant would begin every shoot with a mahurat, a practice Ivory soon came to accept.

Merchant Ivory’s work holds the distinction of being the longest-running collaboration in the field of independent cinema. While their independent status meant that they could skirt the studio mandated regulations that often stinted Hollywood filmmakers, gathering funds and looking for distributors posed a problem. Merchant’s acute business acumen proved invaluable in this regard, opening up avenues for their films in the West. It was Merchant, for instance, who realised that major Hollywood studios had earnings from their films sitting ‘frozen’ in Indian banks that they were willing to invest in productions in India. Columbia bought The Householder from Merchant Ivory with these ‘frozen’ rupees. The Guru (1969) was financed by Fox, while American International Pictures provided the funds for The Wild Party (1975). Even as the success of Merchant Ivory’s A Room with A View (1985) opened the doors for further studio collaborations, they were able to maintain a relative autonomy over the form and subject of their cinema.

Perhaps what distinguished Merchant Ivory Productions from others was the permanence of their core membership—Ivory, Merchant and Jhabvala—as Ivory himself stresses in his interviews. He likened their company to the US government—himself as the President, Merchant as the Congress, and Jhabvala as the Supreme Court. Jhabvala would play arbiter between the two of them, although she, too, had her fair share of disagreements with Ivory, with whom she often shared screenwriting duties. Merchant would also sometimes swap roles with Ivory, even taking up the onus of rewriting certain scenes if necessary. This structural stability ensured that the three established a sustainable rhythm of work with minimal disruptions.

Actors’ Films: The Householder and Shakespeare Wallah

Over the years, Merchant Ivory productions built up a reputation of being actors’ films. Though their films were driven by dialogues and strength of performance above all, Ivory adopted a light-handed approach towards direction. With no rigorous workshops or rehearsals, he would take the actors’ ‘talent for granted in most cases,’ giving them free rein to flesh out their own characters. This did not mean that their films were loosely structured, and their attention to character and setting is evident from their maiden project itself. The Householder starred the fresh-faced Shashi Kapoor, Leela Naidu and Durga Khote, whom Ivory had previously met. By the time Merchant and Ivory had come to meet Jhabvala in Delhi, Shashi Kapoor was already married to Jennifer Kendal. At the very beginning of his career and having starred in a handful of films, Jennifer and the youngest Kapoor ran into Merchant at a party in Bombay. They got along famously, starting off a continued collaboration between Shashi Kapoor, the Kendal family and Merchant Ivory Productions.

Incidentally, Ivory’s idea for their next film, Shakespeare Wallah, happened to line up with the lives of the actors Laura Liddell and Geoffrey Kendal and their daughters, Jennifer and Felicity. Originally conceived as a film about a group of Indian actors travelling across India to perform Western classics, the story was modified to suit Geoffrey Kendal and Laura Liddell’s experiences as part of the repertory theatre group ‘Shakespeareana’, which travelled across the country performing Shakespeare for varied audiences. In Ivory’s recollection, Jhabvala’s interest was captured by the diaries Geoffrey Kendal kept as he travelled and performed: a detailed retelling of how it felt to be a group of English people in India, performing the works of the English bard for an audience that had just about managed to throw off the colonial yoke.

The breadth and scope of Shakespeare Wallah, covering several locations across the country, took some time to come into being. Its predecessor, The Householder, faced some financial difficulties at the very start, and Merchant and Ivory had to pour their own savings into the film. With the cooperation of stalwarts like Subrata Mitra and the actors, the film slowly took shape. Shot in both English and Hindi simultaneously, the film took double the anticipated time in both shooting and post-production. For the comfort of the actors, most of whom were used to acting in Hindi-language cinema, Ivory would shoot scenes first in Hindi and then in English. Despite these accommodative gestures, he remained very much on the margins of the Hindi scenes himself. With the director unaware of the nuances of the language, the work on these sequences was mostly due to the credit of his assistant and the actors themselves. The crew, meanwhile, suffered a similar impediment—most of them were from Calcutta, fluent speakers of Bengali and English, but not Hindi. Set primarily in Delhi, The Householder was a spatially modest film, with a near-Austenian focus on the quotidian life of contemporary Indians. Though it traversed Prem Sagar’s (Shashi Kapoor) workplace and his home, it was remarkably concentrated on private spaces, gently laying bare the intimacies between individuals onscreen. Subrata Mitra’s skilled cinematography imbued these spaces with the languid lyricism often associated with Ray’s cinema, a quiet flourish that came to define the style of the films Merchant Ivory would make for some time to come. Once completed and distributed by Columbia, the film enjoyed moderate success globally. With their earnings from the film, Merchant, Ivory and Jhabvala set out on their next venture, Shakespeare Wallah.

The 1965 release featured a larger cast than The Householder, bringing in actors from theatre and film, like Utpal Dutt, Geoffrey Kendal and Laura Liddell. With Shakespeare Wallah, Merchant Ivory productions moved out of the confines of the home. Following the travelling theatre company, the film’s narrative explored spaces as far-flung as Rajasthan, Lucknow, Shimla, and Kasauli. Landscapes haunted by the remnants of the British Raj occupied the screen, evocatively brought to life by Subrata Mitra’s cinematography and Satyajit Ray’s music. In one section of the film, the troupe puts on a production of Antony and Cleopatra for an ageing maharaja (Utpal Dutt) in a dilapidated palace in Alwar, Rajasthan, with shots lingering pensively on the crumbling ruins and the last flickers of the maharaja’s feudal wealth. Traces of the past in a time of transition leave nothing untouched in the film as it slowly sets about excavating a history of the medium of cinema in India in negotiation with its closest predecessor, the theatre. Even as the narrative depicts, with a great deal of misty nostalgia, the fading form and the penury of the theatre group, the world of cinema and its star Manjula (Madhur Jaffrey) take on a hard shine, a facet of the harsh new world forming in the wake of the Raj.

On its release, Shakespeare Wallah made a strong impression on its viewers. In Ivory’s own estimation, the Indian films that had come to the United States were primarily Satyajit Ray’s works, Bengali-language films with subtitles, centred on Bengali life in and around Calcutta. Shakespeare Wallah, on the other hand, delved into a different difficult history, presenting fragments from the lives of those struggling with the remains of the British Raj—whether they were the newly rich Indians, feudal lords grasping at rapidly disappearing wealth, or the quietly destitute English still in the country. The film’s languorous, elegiac tone, and the wide berth afforded to its characters’ colonial nostalgia came in for criticism, however, with some reading Lizzie’s (Felicity Kendal) ultimate departure for England as privileging Englishness. None of the triumvirates claims otherwise, though, and the inability of those on the outside—here the Buckingham family of players—to fit into a fledgeling world leaving them behind thus finds its place in the second film the trio makes, becoming a recurring concern in a number of their features.

An Emerging Ensemble: The Guru and Bombay Talkie

Undeterred by the mixed responses to the subject matter of Shakespeare Wallah, Merchant Ivory’s next, The Guru (1969), touched upon a controversial topic as well. The Guru was born of an idea James Ivory chanced upon due to his close acquaintance with Indian classical musicians like Ustad Ali Akbar Khan and Vilayat Khan. Fascinated with Graeme Vanderstoel’s close relationship with Ali Akbar Khan, Ivory told Vanderstoel of his wish to make a movie about a friendship between an Indian and a Western musician. Later, as the relationship between George Harrison and Ravi Shankar gained traction in international news, Twentieth Century Fox expressed interest in producing the film, particularly if the disciple happened to be a Western pop star. Starring Michael York as the headstrong disciple, Tom Pickle, and Utpal Dutt as the Guru—who happened to have two wives—the film ran into trouble on the very first day of shooting when Dutt was imprisoned for sedition and had to be released by Merchant. Though the film features lush visuals of the old Bikaner fort and the music of Ustad Vilayat Khan, it did not make great waves with the critics. The model of work that was beginning to emerge for the production house, however, was far more interesting. Ivory and Merchant seemed to have found a loosely collected group of experienced actors to appear in their films, who took turns to play leading roles in the movies, functioning much like an ensemble theatre company.

Merchant Ivory’s carefully constructed ensemble appeared again in their next project, released the following year, titled Bombay Talkie (1970). Starring Jennifer Kendal as Lucia Jane, an English novelist in Bombay to research a book, and Shashi Kapoor as Vikram, a movie star who falls in love with her, the film was meant to mirror and parody Bollywood cinema of the 1960s. Familiar faces like Utpal Dutt, the Hindi film actress Nadira, and Aparna Sen made appearances in important roles as well. The film famously opened with an overblown Bollywood-esque dance sequence featuring Helen dancing on the keys of a giant typewriter as she led a chorus line. The gently mocking tone of sequences like these are offset throughout by a poignant note of yearning for a world past, and even comic sequences are awash with Subrata Mitra’s characteristic lyricism. It is perhaps in Bombay Talkie more than any other film that the clash between Vikram and Lucia’s worlds comes to the fore most violently. Designed to follow the pattern of a typical melodrama, the narrative’s focus on the explosive relationship between the married Vikram and the seemingly guileless Lucia, with Vikram’s wife Mala (Aparna Sen) caught between the two, lends the story its central force. A film about film, and about Bombay, Bombay Talkie was an original conception, written by both Ivory and Jhabvala. Behind the shine of the film lies, yet again, the discomfort of the stranger that marks their Indian features. As Ivory himself says, the film is ‘a demonstration of how things don’t work out,’[1] an outcome that appears to him inevitable for ‘foreigners’ attempting to live and love in India. If communication between two people is difficult, these films seem to say, then that between those from different cultures is impossible, and much of the tragic impetus in films like Shakespeare Wallah and Bombay Talkie draws on the doomed attempt to communicate with the other.

History and Memory: The Documentary Years

The nascent glimmers of Ivory and Merchant’s rumination on the Bollywood film form in Bombay Talkie finds more concrete, documentary shape a few years later, with Helen, Queen of the Nautch Girls (1973). With perhaps the best-known dancing star of the industry appearing in montages—the typewriter scene from Bombay Talkie is resurrected—the thirty-minute long documentary explores the ways in which sexuality and desire appear onscreen, navigating the minefield of censorship and social mores that forbid the depiction of explicit contact between actors. Nestled between Bombay Talkie and Helen, Queen of the Nautch Girls, another documentary made an appearance—Adventures of a Brown Man in Search of Civilization (1972), constructed around the spirited writer and intellectual, Nirad C. Chaudhuri. Chaudhuri was a man full of contradictions, eager to skewer Western preconceptions about Indians, but also opposed to the British withdrawal from India. His garrulity was infectious, and he would often leave Ivory, Merchant and Jhabvala exhausted after their conversations. Perhaps the most representative scene from the documentary takes place when Chaudhuri visits the grave of the orientalist scholar Max Mueller. In a trademark Merchant Ivory moment of cross-cultural connection, the two are immediately brought together by their shared fascination for another culture, even as they are caught in a network of colonial hierarchies of power.

In the same year, the production house also released Savages (1972), an experimental take on the comedy of manners. Two others followed, a telefilm on the life of William Shakespeare in 1973, and Merchant’s directorial debut, a 27-minute short titled Mahatma and the Mad Boy (1974), based on an idea suggested by Sajid Khan. Soon after, a visit to the maharaja of Jodhpur, a friend of Merchant’s, prompted the germination of Autobiography of a Princess (1975) and Hullabaloo Over Georgie’s and Bonnie’s Pictures (1978). The former, still lauded as Merchant Ivory’s most accomplished study of character, was a chamber drama exploring the deceptive nature of memories and the difficult process of accepting the past for what it was. Starring Madhur Jaffrey as an Indian princess living in London, and James Mason as her father’s disenchanted secretary, the film was a 60-minute long sketch. The Umaid Bhawan palace spurred much of both Autobiography and Hullabaloo, belying Ivory’s assumptions about an Indian palace with its art deco aesthetic. In Hullabaloo Over Georgie’s and Bonnie’s Pictures, the palace served as the backdrop for the attempts of four individuals to locate a collection of Indian miniatures as a bemused maharaja looks on. Its slightly comic yet elegiac tone made the film one of their most successful productions. Featuring an ensemble cast led by Victor Bannerjee and Aparna Sen, the film once again excavates an ossified past, bringing it into contention with the march of modernity. Ironically, the maharaja himself cares little about the paintings and is more taken with photography. The ambiguity of the central characters is further underscored by their names, Georgie and Bonnie, bestowed upon them by Scottish governesses, inscribing traces of a colonial past onscreen. Much like Shakespeare Wallah and Adventures of a Brown Man in Search of Civilization, these are people sitting slightly awry with their times, becoming strangers in their own homes.

The Sun Sets: Merchant Ivory’s Last Films in India

Their next major venture set in India, Heat and Dust (1983), adapted from Jhabvala’s Booker-Prize-winning novel, appeared at an opportune moment. India had arrived on the British screen, with Gandhi (1982) released the previous year and A Passage to India (1984) in the next. Heat and Dust was a rousing success, earning eight BAFTA nominations and a Palme D’Or nomination at Cannes. Bringing back old favourites Shashi Kapoor, Madhur Jaffrey and Jennifer Kendal along with Greta Scacchi and Julie Christie, the film placed two English women and their desires, sexuality and agency at the heart of its plot. Anne (Julie Christie) arrives in the town of Satipur trying to retrace the steps that her great-aunt Olivia had taken fifty years ago. Their fates seem to mirror each other, and in Ivory’s own words, ‘Both sink or disappear in the Indian life and find their fulfilment there.’ In both cases, the women feel alienated from the stultifying English way of life but are forced to take drastic measures to avoid the punitive force of a patriarchal society. The film boasted higher production values than their others and was gorgeously photographed by Walter Lassally. It earned some amount of flak from Indian critics due to the comic depiction of the nawab, played by Shashi Kapoor. It would also be the last to be directed by Ivory in India.

The theme of immersion returns again in their final production in India, 1988’s The Deceivers. The intervening period was marked by some high-profile adaptations, among them The Perfect Murder (1988), starring Naseeruddin Shah as Inspector Ghote, a character from H.R.F. Keating’s mystery novels. Directed by Nicholas Meyer, The Deceivers revolved around the efforts of the protagonist, Captain William Savage, to bring down a gang, and the psychological consequences he suffers. The anxiety held in the title of the film itself is foregrounded, betraying the unease of the coloniser confronted with a subject not adhering to normative conduct. Instead of being loyal defenders of the colonial capital, the Thuggees ‘deceive’, laying a claim to the coloniser’s accumulated wealth. Unfortunately, the film’s tonal difference with earlier Merchant Ivory films sits ill at ease, marking a tepid end to the long association of the company with the Indian setting.

If there is a common thread in Merchant Ivory’s Indian productions it is their fascination with the remnants of time, carefully unpacked through an attentive yet distant gaze. When not adapting from Jhabvala’s works, the writers they adapted were also mostly expatriates—the likes of Jean Rhys, E.M. Forster and Henry James. Coupled with their unique cultural (dis)location is the fact that their productions enjoyed the dual status of being both global and local. Their cast and crews involved a large number of Indian artists, whereas through Merchant’s industrious manoeuvrings they often had funding from foreign bodies. This duality often gave rise to unique cultural conflicts and complicated their films’ critical reception. Critics of a liberal persuasion found their images ethically suspect in their obfuscation of class and racial lines to romanticise a colonial past, while some conservative critics appreciated their measured, novelistic approach. But the lines are perhaps not so easy to draw when it comes to Merchant Ivory productions. With sexuality and the impossibilities of desire often the central theme of their features, the introspective tone of their films has come to be associated in contemporary feminist and queer criticism with an emotionally charged staging of male sexuality that transgresses the bounds of heteronormativity.

While the impossibility of truly intercultural cinema is worth pondering, Merchant Ivory’s films shy away from such grand claims. Their cinema is characterised by a far more modest translational attempt. Attempting to translate—and thus communicate, to an international audience—the wounds of colonialism and the entangled identities left in its wake is no small task, and their films often leave something to be desired in this regard. Aware that their audiences found their depiction of a ‘clash of cultures’ appealing, they never claimed to be anything more than outsiders with intimate links to India, to them both astonishing and fascinating in its multiplicity. Their most successful films conveyed these feelings with a sense of ironic humour, tiptoeing around the emotional turmoil of melodrama but never fully taking the plunge. In a world where borders between people are drawn more clearly with every passing day, it is perhaps Merchant Ivory’s insistence on the scars left behind by political events at large, and their effect on the quotidian lives of many, that deserves to be held on to. Communication—and film, like all other media, is only an endeavour to converse—may be ultimately impossible, but it is in the gaps of this exchange that any work of art, however troubled, comes into being.

Notes

[1] Varble, 'Interview with James Ivory,' 23–24

Bibliography

Chatterjee, Partha. ‘The Last Maverick: Ismail Merchant.’ India International Centre Quarterly 32, no. 4 (SPRING 2006): 29–41. Accessed October 14, 2020, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23005892

Long, Robert Emmet. ‘Feature Films: India.’ In James Ivory in Conversation: How Merchant Ivory Makes its Movies, 69–70. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 2005.

MacKay, Kate and Graeme Vanderstoel. ‘James Ivory in Person & Five Questions for Graeme Vanderstoel.’ BAMPFA. Accessed October 14, 2020, https://bampfa.org/news/james-ivory-person-five-questions-graeme-vander….

Majumdar, Neepa. Wanted Cultured Ladies Only! Female Stardom and Cinema in India, 1930s-1950s. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, year.

Mohan, Jag, Basu Chatterji, and Arun Kaul. ‘James Ivory and Ismail Merchant: An Interview.’ In Merchant-Ivory Interviews, ed. Laurence Raw, 6–8. Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2012.

Monk, Claire. ‘The British “heritage” Film and its Critics.’ Critical Survey 7, no. 2 (1995): 116–24. Accessed October 14, 2020, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41555905.

Varble, Stephan. ‘Interview with James Ivory.’ In Merchant-Ivory Interviews, ed. Laurence Raw, 23–24. Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2012.

Yenning, Dan. ‘Cultural Imperialism and Intercultural Encounter in Merchant Ivory's “Shakespeare Wallah.”’ Asian Theatre Journal 28, no. 1 (SPRING 2011): 149–67. Accessed October 14, 2020, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41306474.