Manjusha in Sanskrit means ‘box’. The word is used for the ceremonial temple-shaped bamboo, jute straw and paper boxes used by devotees to store items for Bishahari Puja. The Manjusha boxes signify the box that is said to have covered the body of Bala Lakhendra in the folklore of Bihula-Bishahari. According to the legend, the temple-shaped box, known as manjusha, was adorned with Bihula’s story along with the flora and fauna of Anga, hence is said to be the point from where the art form of the same name originated. To understand the significance of Manjusha art, it is essential to know the folklore of Bihula-Bishahari.

According to the legend, one day Lord Shiva was taking bath in Sonada Lake and five strands of his hair fell into the water. These strands became five lotuses at the bank of the lake. All the five lotuses requested Lord Shiva to accept them as his daughters, to which Shiva replied that without seeing their true form, he cannot accept them. The five lotuses converted into their true forms of five sisters: Jaya Bishahari, Dhothila Bhavani, Padmavathi, Mynah Bisahari and Maya Bishahari/Manasa Bishahari.

Lord Shiva accepted these five women as his Manasaputri (daughters in human form).

The five sisters then went to Goddess Parvati and asked her to accept them as her daughters, which she refused. The sisters got agitated and turned themselves into their snake form and hid in the flowers. When Goddess Parvati went to pick the flowers, the snakes bit her and she was unconscious, which is when Lord Shiva came and requested them to revive her with the assurance that she will accept them. Jaya Bishahari fed Goddess Parvati amrit (elixir of life) from her amrit kalash (pot) and revived the goddess. As she came back to life, Parvati granted them a boon saying that from then on they could rid people of snake poison, thus they earned the name Bishahari (one who can rid you of poison).

One day, the five sisters approached Lord Vasuki Nag and told him that since they are Lord Shiva’s daughters, they should be worshipped as well. Lord Vasuki Nag replied that in the kingdom of Anga Pradesh in Champanagar, there is a Lord Shiva devotee, Chando Saudagar; if he decided to worship them, everyone else on earth will follow. On hearing this, the five sisters asked for Lord Shiva’s permission to meet Chando Saudagar and headed towards Champanagar. Chando Saudagar was a very successful businessman. When the sisters approached him and asked him to worship them, Chando Soudagar said that he did not know who they were and so cannot be their devotee. On hearing this, Mynah Bishahari got angry and cursed Saudagar that if he does not worship them, they will ruin his business and kill his family; however, even this threat could not deter him.

The Bishaharis pledged to take their revenge. So, when one day Chando Saudagar was travelling with his six sons in a boat, they drowned the entire family. Soon after though the Bishaharis realised that Saudagar’s death would mean they would never be worshipped. They prayed to Lord Hanuman for help and he pulled Saudagar out of the river. Saudagar survived but he still refused to change his mind. As time passed, Saudagar and his wife had their seventh son Bala Lakhendra. The son grew up and the parents fixed his marriage to a girl named Bihula from Ujjain.

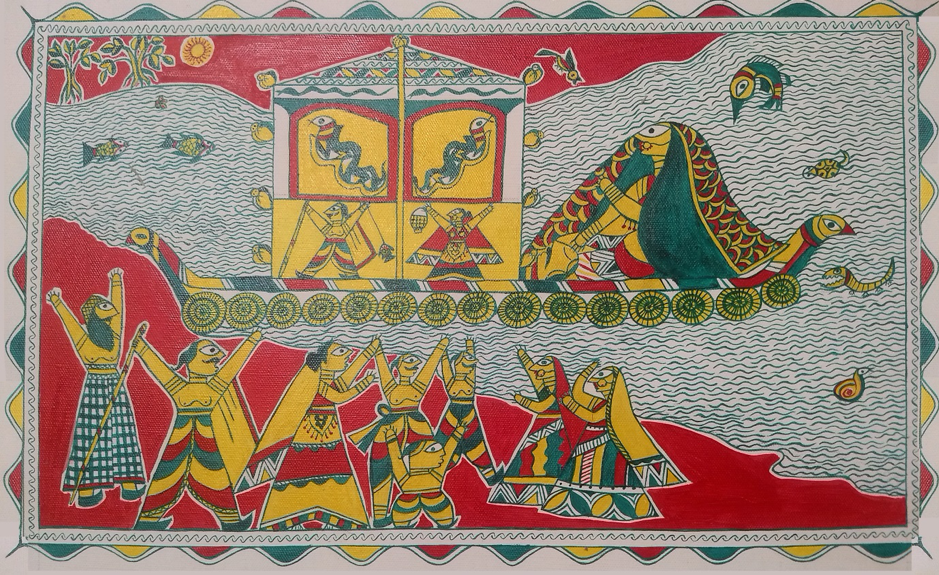

The wedding of Bala Lakhendra took place with much pomp and Bihula was brought from home. Always aware of the threat of the Bishaharis, an iron house was constructed by Lord Bishwakarma for the couple’s wedding night. The Bishaharis, however, figured out a hole thin as a hair in the wall of the couple’s room through which they managed to slip in Lord Shiva’s snake Maniyar who bit Lakhendra to death. Bihula, distraught at her husband’s death, started crying, alarming the rest of the family. Chando Saudagar was about to order that his son’s body be immersed in the river, when Bihula stopped him and said she will travel with her husband’s body and approach Goddess Nethula Dhobin to revive him. Bihula ordered the same Bishwakarma who had constructed the house to build a boat and a cover for her husband’s body; he built the boat and a manjusha. Bihula also requested an artist to draw the story of her tribulations on the manjusha, along with drawings of her family and the flora and fauna of Anga Pradesh. The colour palette chosen was such that it evoked sacrifice, determination and happiness.

After lots of trials and tribulations, Bihula managed to reach Nethula Dhobin who guided her to Lord Shiva in heaven; Bihula was wearing ghoonghat (headscarf) which covered her face from the god. She requested Lord Shiva to return her husband’s life and also to return her father-in-law’s wealth back to him. Her boons were granted but as soon as her ghoonghat was removed, the Bishaharis recognised her; they told her that her boons would come true only if Chando Saudagar agreed to worship them. Saudagar, in order to save the life of his son, finally had to give in; and that is how Bishahari puja came into being.

Manjusha Art and the Region of Anga Pradesh

The Indian subcontinent has, over centuries, witnessed the rise and fall of many empires. Present-day Bihar and the regions around it have been home to three mahajanapadas (16 kingdoms of ancient India, from sixth to fourth centuries BCE) of the Vedic period, including Anga, Magadha and Vajji. The boundaries of these three mahajanapadas were defined by geographical features, namely the two rivers, Ganga and Champa. The area north of the Ganga River—mainly northern Bihar, including the region of Mithila—comprised the state of Vajji, while Magadha and Anga were separated by the Champa River. The region and expanse of Anga holds an important place in the narrative of origin and development of the Manjusha art form.

Anga finds an early reference in Atharvaveda (one of the four vedas, which are sacred texts of Hinduism), where the residents of this janapada find mention along with Magadhas, Gandharis and Mujavats. Ramayana and Mahabharata also mention the kingdom of Anga, with each citing different reasons for why the region was called by that name. According to the Ramayana, the region came to be known as Anga because Ananga (Kamadeva) lost his body after being turned to ashes by Shiva’s anger there. According to the Mahabharata, this expanse was named Anga (also Anga Pradesh) after Anga (son of Bali, king of Kishkindha in the Hindu epic Ramayana) and was given to Karna by Duryodhana.

Anga was located in the easternmost region of India. On the northern side, the kingdom of Anga was bound by Vajji and Kosi Rivers while on the western side stood its rival kingdom of Magadha. The capital of Anga, Champa, was located at the confluence of the rivers Ganga and Champa (also known as Chandan or Malini). The region flourished until it was annexed by the Magadha empire under the rule of Bimbisara in the sixth century BC.

Today, the kingdom of Anga roughly corresponds to the districts of Araria, Bhagalpur, Banka, Purnia, Munger, Lakhisarai, Begusarai, Jamui, Katihar, Khagaria, Kishanganj, Supaul, Saharsa and Madhepura in Bihar; Deoghar, Godda, Pakur, Dumka, Jamtara, Giridh and Sahebganj in Jharkhand; and Malda, Birbhum and Uttar Dinajpur in West Bengal.

The ancient city of Champa was an important centre of trade and commerce, and the folklore of Bihula-Bishahari was woven at the heart of it, which in turn gave birth to one of the most celebrated festivals of Bhagalpur, Bishahari Puja, as also the Manjusha art form. Champa has been linked with the present-day settlements of Champapur and Champanagar and is located at an approximate distance of 9 km to the west of Bhagalpur city in southern Bihar.

The foremost evidence in firming up the exact location of Champa comes from Chinese monk, scholar and traveller Hiuen Tsang’s travelogue and the writings of British army engineer Alexander Cunningham. According to Hiuen Tsang, Champa was located to the west of a hill crowned with a temple that Cunningham identified as hill of Patharghata, located at a distance of 24 miles from Champa village (in today’s context).[1] This link helps in establishing geographical as well as factual credibility to the folklore because it coincides with the storyline where Chando Saudagar is said to belong from a city named Champanagar in Anga Pradesh. The auspicious and celebrated ghat known as Bihula Ghat is located in today’s Champanagar (near Nathnagar to the west of Bhagalpur) at the confluence of the rivers Ganga and Champa, which has now been reduced to status of a nala (ravine). It is said that from Bihula Ghat, Sati Bihula sailed with her dead husband Lakhinder in search of blessing from Goddess Manasa. An annual fare commemorating Bihula is still held in Champanagar, and the oldest temple of Manasa was built in this locality.

The geographical location of this city as well as of the kingdom of Anga helps in deriving another important conclusion as to why the festival of Bishahari Puja and the Manjusha art form is known and celebrated only in the present-day Bhagalpur region of Bihar and not in other parts of the state: it is because the kingdom of Anga was separated from Magadha and Vajji by rivers, resulting in slight differences in landform, flora and fauna. Anga’s geographical location helped keep it isolated from the other two kingdoms, which in turn resulted in different culture, tradition, art and crafts. But it will be incorrect to say that the three kingdoms were not influenced by one other, especially after Magadha took over Anga in the sixth century BC. The distinction between these geographical regions, however, remained and is still apparent not only in terms of festivals and art but also the dialect and lifestyle of the people.

Origin and History of Manjusha Art Form

Artists practising the Manjusha art form believe that it is contemporary to the time period of the Indus Valley Civilisation. In an interview, Manjusha guru Manoj Pandit[2] points to an excavation carried out in 1970–71 in Karnagarh, a mound 3 km to the west of Bhagalpur and identified by Buchanan in 1939, carrying remains of ‘a square rampart surrounded by a ditch’.[3] In that excavation, several items, including terracotta figurines and embellishments of nagas (snakes) similar to motifs represented in Manjusha, were unearthed. When these figurines were dated, they were found to belong to the same time period as the Indus Valley Civilisation, hence it is believed that Manjusha art form dates back to 2600 BC.

The art form was earlier practised by families of only two castes—the Kumbhakars and Malakars. The Kumbhakar caste is known to make pots on which Manjusha art is done and later worshipped during the festival of Bishahari Puja; people of the Malakar caste are known to make the ceremonial boxes, or manjushas, and paint on them abstracts of the folklore.

The legacy of this art form is not limited to ceremonial boxes and pots but also manifested in the bhitta chitra (murals). Manjusha bhitta chitra was done on three areas of homes—the outer walls, the place of worship and the newlyweds’ room. Given the storyline of Bihula-Bishahari, Manjusha was deemed important for newlyweds, and abstracts from folklore were painted in their room to bring good fortune to the couple. The folklore not only inspired this art form but was also a driving factor behind an oral tradition where the story of Bihula-Bishahari, or ‘Bihula-Bishahari Gatha’ as it was termed, was sung in the local dialect during the puja. This tradition is currently not as popular but one can hear recordings of the songs played during puja, indicating the significance of oral history.

The folklore was an integral part of the everyday lives of people living in Anga Pradesh but it was more or less concentrated in this region until it was brought to the forefront by a British officer. In early 1930s, ICS officer W.G. Archer and his wife visited this region and noticed the paintings on ceremonial boxes during the festival of Bishahari Puja. They started researching this art form and, with the help of local people practising it, put together a collection of Manjusha paintings. This was probably the first time when this sequential depiction of Bihula’s story was transferred from boxes and pots to canvas. An exhibition was organised at the India Office Library in London where it became a part of the Archer Collection. So during 1931–45, Manjusha art gained an international recognition after which many people started learning it. However, after the fall of British Empire, there were no patrons for Manjusha and as a consequence the art form started losing its value, and only a handful of people continued it.

Process of Making the Art Form

When a painting is started for religious purposes, the artist makes a pile of rice in the room, places a betel leaf with a betel nut on top of this pile, and prays for permission from the goddesses to start the painting. The moment the leaf shifts a bit or falls, they consider this as a sign that they have got permission and can start their work.

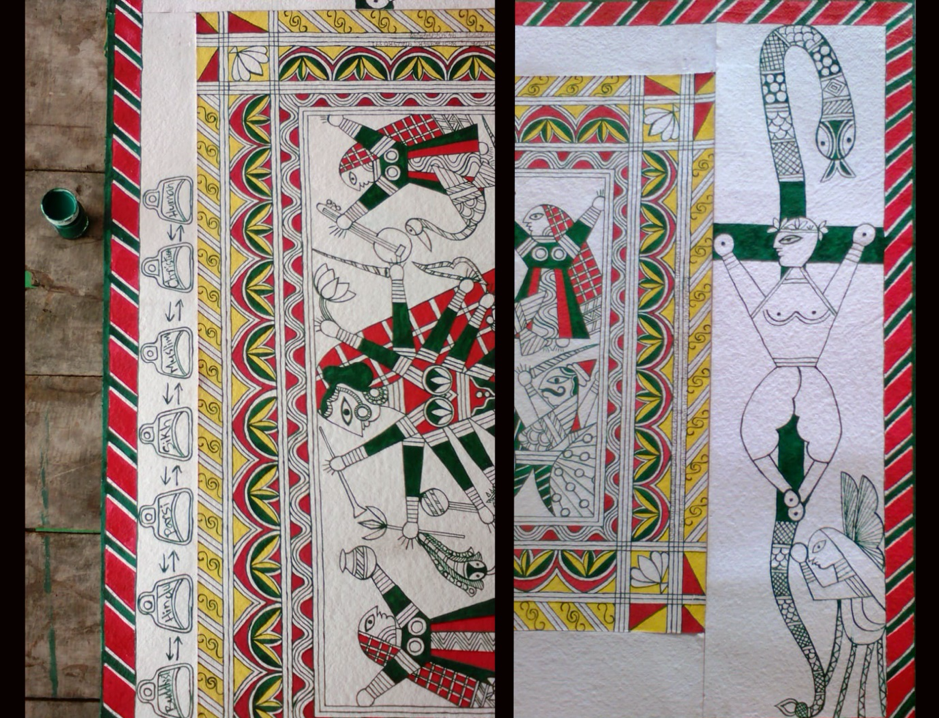

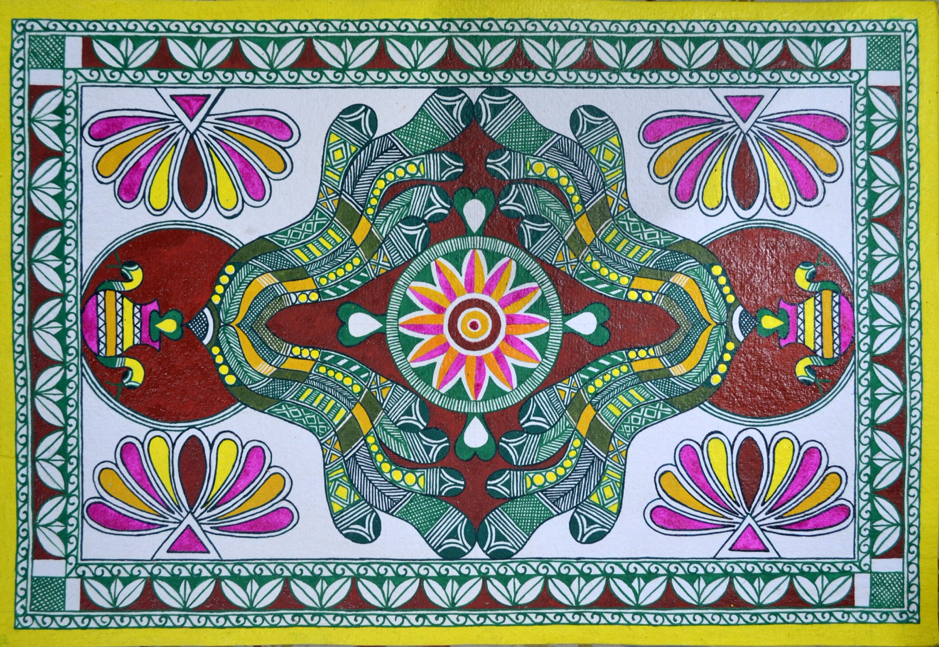

For the painting, first an outline is drawn and then colours are filled in. (Fig.1) The outline is usually drawn in green, but today some artists also use black colour. In traditional paintings, rulers and other instruments were not used as it was felt that the little imperfections added to the raw nature of the art; however, nowadays various instruments are used to make the paintings symmetrical and precise.

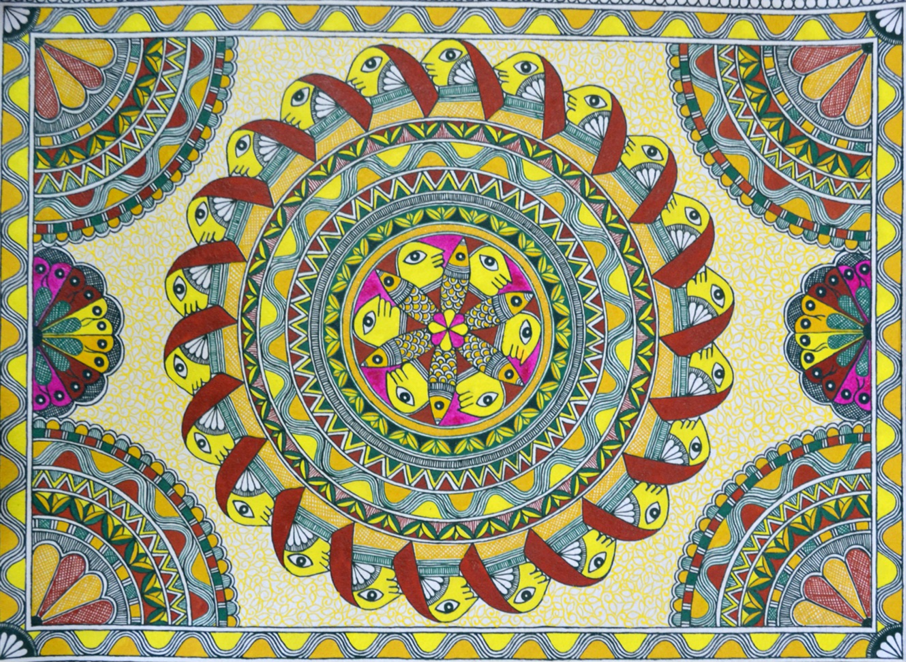

Apart from portraying the folklore of Bihula-Bishahari, artists have started using other motifs and characters for composing abstract paintings and artworks while experimenting with the shade and hue of colours. (Figs 2 and 3)

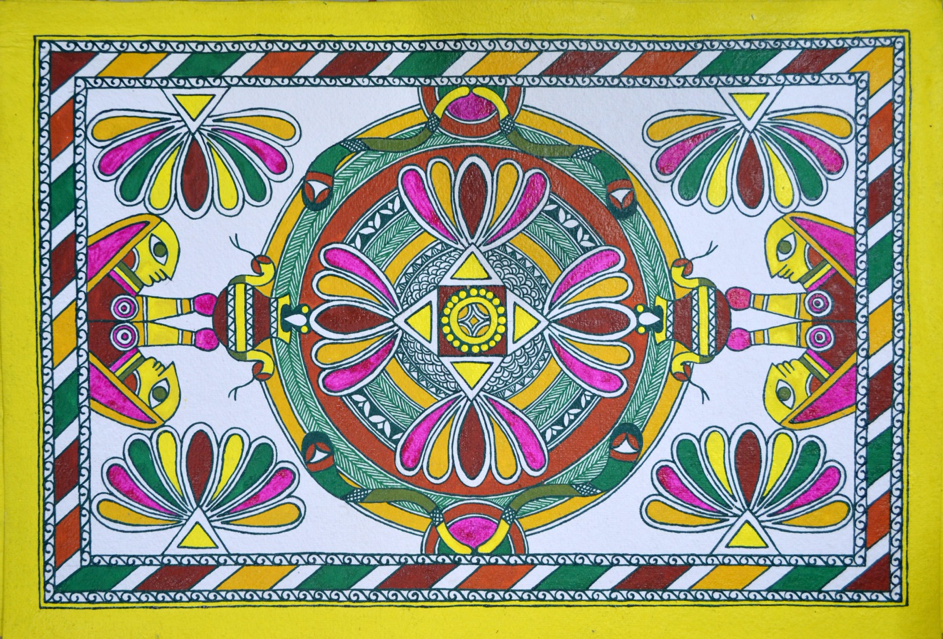

Borders are very important in Manjusha paintings (Fig. 4); motifs such as leheriya, sarp ladi, tribhuj, mokha and belpatra are generally used for making borders. Sometimes, artists also use a solid band of yellow, green or pink colour after these motifs to enclose the painting and make it look complete. (Fig. 5)

Belpatra (wood apple leaf) motif signifies leaves of bel tree which are offered to Lord Shiva and said to be extremely dear to him (Fig. 6); leheriya signifies the course of the river and the ripples that arose in water when Bihula took the body of her husband in a boat covered with manjusha; sarp ladi signifies group of snakes that Goddess Manasa commands; and mokha has been carried from the Manjusha bhitta chitra.

Most of the important motifs represent some or the other form of nature such as belpatra, champa (plumeria), scales of fish and motifs representing snakes. The kalash, borrowed from the amrit kalash of Bihula-Bishahari folktale, is also a recurring motif used in Manjusha art during Bishahari Puja.

Characters and Motifs in Manjusha art

All the characters in Manjusha paintings are drawn in a distinct manner. Human forms are depicted in the form of letter ‘X’ with raised limbs. The main characters are portrayed with big eyes and without ears. Bishaharis are represented in the same way except they can be distinguished by what they hold in their hands: Jaya Bishahari holds a bow and arrow with amrit kalash in one hand and snake in the other, Dhotila Bishahari has a rising sun in one hand and a snake in the other, Padmavathi Bishahari has lotus in one hand and a snake in the other, Mynah Bishahari has mynah in one hand and a snake in the other, and Maya/Manasa Bishahari holds snakes in both hands.

Recent Developments

Manjusha art was on the verge of extinction when in the 1980s the Bihar government stepped in to save it from fading into oblivion. In 1984–85, the Jansampark Vibhagh (Department of Information and Public Relations) started an initiative to provide a boost to Manjusha art and create awareness among citizens. Officers of the department worked closely with the few artisans still practising it and made slideshows depicting their work. The slideshows were then shown in villages of Bhagalpur district, and residents were educated about the significance of Manjusha art so that it could be revived.

As a result of this initiative, some people came forward to help spread Manjusha art. First and foremost were Chakravarty Devi and Jyoti Chand Sharma. Chakravarty Devi belonged to the Malakar caste, who were involved in making manjushas, and she helped give a new direction to the artisans. For her efforts she was awarded the Bihar Kala Award (also known as the Sita Devi Award) by the Government of Bihar. Jyoti Chandra Sharma wrote diligently about this art form. In addition, two other prominent people, Champanagar residents Basant Pandit and Chhedi Pandit, who belonged to the Kumbhakar caste, became actively involved in its revival. The pots used for puja in the oldest temple of Goddess Bishahari, in Champanagar, came from their family. During the same time, Shrimati Nirmala Devi also started working diligently and received the Bihar Kala Award in 2013 for her work.

Another name that won recognition in the 1990s was that of Manoj Pandit, the face of Manjusha art in this millennium. Son of Nirmala Devi, Manoj Pande is a fine arts degree holder from Prachin Kala Kendra, Chandigarh. His experiments with different materials like silk and other fabrics helped artisans take this art form to a wider audience. He was involved in conducting workshops, exhibitions and training initiatives to help artisans make Manjusha a means of livelihood; for his work, he was awarded with the title of Manjusha Kala Guru by the Ministry of Culture in 2014.

In 2007, Disha Gramin Vikas Manch (DGVM), a community-based non-profit organisation collaborated with the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) to work towards creating livelihoods through Manjusha art. Manoj Pande from DGVM and Nabin Roy (District Development Manager) from NABARD Bhagalpur were instrumental in making this project a success. As a development finance institution, NABARD understood linkages with livelihoods for the art to survive and supported a rural innovation project to revive Manjusha art; they also started an activity-based group programme for two clusters of Naugachia and Sahkund blocks to create awareness about Manjusha art and establish a connect with the new set of artists: schoolchildren, housewives, self-help group members, etc., were all roped in.

Manjusha art started to get recognition, and with frequent help from the state and/or district administration, the motifs were used to popularise government schemes like Chief Minister’s bicycle scheme, Beti Padhao Beti Bachao, Midday Meal Scheme, etc. Banks were roped in to mete out the credit needs of artisans. The projects were carried out in stage—entrepreneurship development started in 2007, the rural innovation fund project started in 2008, exhibitions, marketing, rural marts, etc., were started 2008 onwards while activity-based groups were started in 2010.

Apart from this, more than 15 villages in each block of Bhagalpur were covered through the mass-contact programme, and NABARD’s Gramin Udyami Mela brought the art form in direct contact with the urban population. Weavers’ service centre, many community-based organisations (CBOs) and social-sector organisations were some of the other organisations working for development of the art. According to Nabin Roy, geographical indication (GI) for Manjusha art is likely to be awarded shortly, which will usher in myriad development initiatives. Mudra loans, Standup India loans, Farmer Producer Organisations, marketing startups and design development leading to product development have now become part and parcel of Manjusha art.

Artists are now experimenting and keeping the religious motifs intact; the art form is now ready to plunge into fabrics, upholstery, decorative items and artefacts.

Today, many artists in Bhagalpur and Patna are working towards making this art form a success. Ulupi Jha, a resident of Bhagalpur and an artisan working actively in this field, has been identified by the Ministry of Women and Child Development as one of the 100 successful women in India. She works closely with the state government and Upendra Maharathi Shilp Anusandhan Sansthan (UMSAS) to organise training workshops for artisans and students who wish to practise this art form. There are new-age artisans as well, like Soma Roy; a graduate from NIFT and a resident of Patna, who has been awarded the state award in 2015–16 for her innovative work in Manjusha art; she also works closely with UMSAS.

Usha Jha, an entrepreneur who lives in Patna and heads an enterprise called Petals Craft that showcases handicrafts mainly of Mithila and Manjusha art work, believes, ‘In order for this art form [Manjusha] to flourish, there is a need to bring flexibility in the way that it has been practised. This includes experimentation with materials and especially colour. The three colours used traditionally are not crowd pleasers and that is why artisans have started using other shades to reach audiences. Artisans have started experimenting but there is still a long way to go. The efforts of the government of Bihar should be appreciated as they have succeeded in bringing this art form out from oblivion.’

To train budding artists, who later take part in the same workshops as trainers, not students, workshops and exhibitions are organised in Bhagalpur with the help of the state government, UMSAS and local artists. Manjusha art work can be seen on the walls of a few government offices in Bhagalpur; the number is only going to increase as the initiative continues under the Bhagalpur Smart City Project.

Notes

[1] Sinha, Archaeology and Art of India.

[2] Art News Network India, ‘Manjusha Art: Interview of Manjusha Guru Manoj Pandit by Sunil Kumar.’

[3] Sinha, Archaeology and Art of India.

Bibliography

Art News Network India. ‘Manjusha Art: Interview of Manjusha Guru Manoj Pandit by Sunil Kumar.’ YouTube video, 6:52. August 13, 2018. Accessed January 29, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mDanudrCTqc.

Sinha, B.P. Archaeology and Art of India. Delhi: Sundeep Prakashan, 1979.