Prakrit languages attained the status of languages of religion, culture and communication owing to their association with the Jain spiritual guru Mahavira who is said to have preached his sermons to Jain mendicants in Prakrit.

The preference for the literary use of a particular variety of Prakrit depended on factors such as religious affiliation, geography, social standing, gender, etc. Despite this linguistic pluralism, works written in Prakrit were seldom multilingual. Polyglot verses in Maharashtri and Magadhi Prakrits appeared for the first time in two episodes of the Jain narrative literature Manipaticharita, which gets its name from a king named Manipati (literally ‘the lord of jewels’) who turns into a Jain muni (‘ascetic’).

In both the episodes of Manipaticharita, verses in Magadhi were uttered by the protagonist, Magadhasena, a courtesan from Magadha.

Story of the First Episode: ‘Magadhasena’s Replies’

In the first episode, Magadhasena outwits her husband in a verbal combat while in the second, she saves her merchant lover from the wrath of the king.

In the first episode of Manipaticharita, ‘Magadhasena’s Replies’, we read about the benevolent king Shrenika who decided to bring presents for his two queens, Cellana and Nanda; to Cellana, he gave an eighteen-fold necklace and to Nanda he offered a pair of spheres. When Nanda saw her present, she exclaimed, ‘Am I a child that you present me playthings?’ and out of anger, smashed the present against a pillar. The two spheres broke open, from one emerged a pair of earrings and from the other a pair of dresses. Cellana demanded that they be given to her but Shrenika said, ‘As you are the most beloved, I gave you the divine necklace whilst to her no more than these playthings. The earrings and clothes emerged from them owing to her merits. How is it appropriate for them to be presented to you?’ Then Cellana spoke again, ‘If you do not give these to me, I shall die.’ The king exclaimed, ‘Do as you like!’

On hearing the unkind words of the king, Cellana got up angrily and climbed up a lofty window of the palace. As she was about to leap off, she overheard an exchange between the rider of the royal elephant and his wife Magadhasena. ‘I’ll listen to their quarrel first and then jump,’ Cellana stood there with this thought in mind. Magadhasena was speaking to her husband in the Magadhi language the characteristic of which is that (the sound) ‘r’ is pronounced as (the sound) ‘l’.

Magadhasena: A festival of the courtesans is in progress here in the city. Adorned in their finery, the courtesans will go to the park. Therefore, O beloved, fetch me the champaka garland, ornament of the royal elephant Sechanaka so that I shall look the best.

Mahout: O my darling! My dear! The king will certainly get angry at this.

Magadhasena: If you do not bring me the garland, then here in the city of Rajagriha in the festival of the courtesans, filled with men and women, I shall abandon my life in the lap of my beloved.

Mahout: A fish does not live for long on land, fire does not stay ablaze in water and a drum does not resound for long by the blows of the spikes. Do you wish to destroy us?

Magadhasena: The fish must live, fire must be lit and the drum must be played. Whether for long or for short, that remains to be seen! If you will not give me the excellently adorned garland resplendent with a string of pearls, I shall abandon my life in the lap of my beloved.

Mahout: A thread that is overstretched snaps, a branch that is overbent breaks and a wife who speaks thus brings misfortune to her good man.

Magadhasena: Not every thread that is overstretched snaps nor every branch that is overbent breaks nor every wife who speaks thus brings misfortune especially when she thinks that her good man is actually a bad man!

If you do not bring me the garland, then here in the city of Rajagriha in the festival of the courtesans, filled with men and women, I shall abandon my life in the lap of my beloved.

Mahout: Why do you torture yourself, O Charioteer? A castor plant that is overbent does not yield but gives away; such is the nature of bad trees and plants!

Magadhasena: Something that is faulty only in name need not be bad in its entirety. A castor plant is certainly useful for other purposes.

If you do not bring me the garland, then here in the city of Rajagriha in the festival of the courtesans, filled with men and women, I shall abandon my life in the lap of my beloved.

Mahout: Why do you tire yourself, O Gardener? The neem tree that you are watering will only yield bitter fruits for such is the nature of bad trees and plants.

Magadhasena: Is something that is useless in one place not beneficial elsewhere? The fruit of the neem tree when spoilt is useful for medicinal purposes!

Now, if you do not bring me the garland, then here in the city of Rajagriha in the festival of the courtesans, filled with men and women, I shall abandon my life in the lap of my beloved.

Mahout: He is of a swinish nature who cuts the roots of the very tree whose flowers and other products he consumes and under whose protection he dwells.

Magadhasena: He who steals the property of one may be the preserver of the property of another. Not everyone who causes destruction thus is akin to a pig.

If you will not give me the excellently adorned garland resplendent with a string of pearls, I shall abandon my life in the lap of my beloved.

Mahout: There will indeed be hundreds of women for me, my dear! If you do not learn this lesson well, you will die without marital bliss. (Translated from the original by the author)

Hearing this, Queen Cellana thought, ‘If I die, what would that mean to Shrenika? There are certainly many other women available for him.’ So, she refrained from the idea of death and passed her time happily.

A Tale of Two Prakrits: The Politics of Language

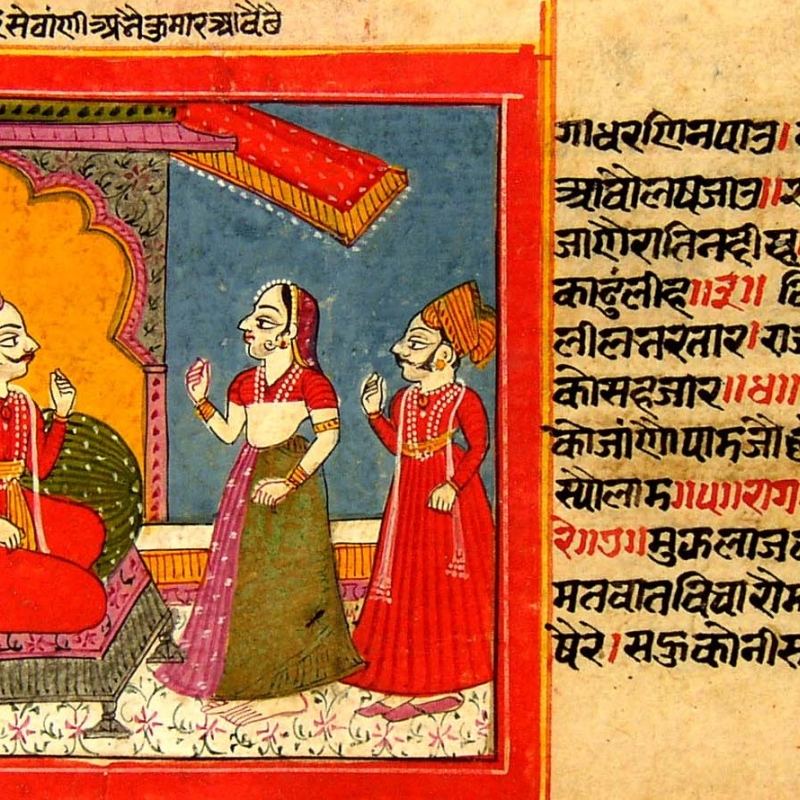

While it is not uncommon for Sanskrit dramas to feature the use of different Prakrits, bilingualism or multilingualism in the context of Prakrit texts is a rare occurrence. In that respect, the conversation between the mahout and his wife showcases a very old and unique specimen of bilingualism in Prakrit katha (religious) literature. (Fig. 1)

The mahout speaks Maharashtri, the language of the text, while the wife responds in Magadhi. Maharashtri, according to Prakrit grammarians, was the standard form of the Prakrit language. Magadhi, as the name suggests, was spoken in the eastern parts of the Indian subcontinent particularly around the province of Magadha. However, Magadhi was also associated with the low caste and the poor people. A hierarchy in language usage is too easy to miss even in Sanskrit dramas where the men of the court converse in Sanskrit while their wives talk in Prakrit. The very fact that Magadhasena uses Magadhi, a lesser tongue, can be attributed to the idea that as a woman her social standing is pretty low when compared to her husband, more so because she belongs to the class of courtesans. In any case, Magadhasena’s replies to her husband’s words are sharp and witty, a rare instance of a woman outwitting a man in verbal combat in Prakrit literature.

The Episode Preceding the Story: Across Language and Geography

It is likely that the story of Magadhasena was in circulation much before the composition of the Manipaticharita. It was probably interpolated by the poet himself or later redactors. This can be deduced from the metrical arrangement of the text. While all verses in Maharashtri Prakrit have been rendered in a metre known by the name of Arya, those in Magadhi show a mix of Arya and Vaitaliya. As if in continuation with the previous frame story, the opening lines of Magadhasena’s words reflect the use of Arya while her subsequent rejoinders reflect the use of Vaitaliya. Moreover, the story of Magadhasena is set in the province of Magadha in eastern India but the Manipaticharita was in circulation in western India. To acquaint his audience with the Magadhi language, the poet himself described its characteristics through the explanation of the sound ‘r’ changing to ‘l’ as can be found in the transliteration of the story.

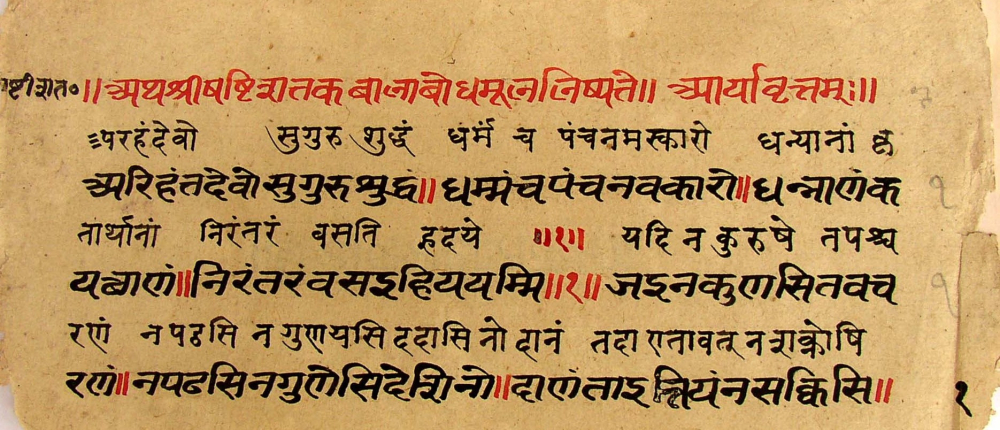

Manipaticharita transliterated

301. tatthayaSeṇiya-rāojaṇa-vañchā-dinna-guru-cāo

302. lāvaṇṇa-rūva-jovvaṇa-guṇa-maṇi-Rohaṇa-girinda-bhūmīo

do bhajjāoanteurassasayalassasārāo

303. egāHehaya-kula-vaṃsa-tilaya-Ceḍaya-narinda-dhūyājā

Cellaṇa-devībīyāNandānāmeṇavaṇi-dhūyā

445. so aṭṭhārasa-vakko aha hāroCellaṇāedevīe

tahavaṭṭa-golaya-jugaṃNandāeSeṇiodei

446. kimahaṃbāla-sarūvābālāṇaṃkhellaṇaṃ jam appesi

roseṇaṃapphuḍeikhambhebhaggaṃ ca gola-jugaṃ

447. egattokuṇḍala-jugaṃavarāokhoma-jualayaṃladdhaṃ

Cellaṇa-devīmaggaitaṃ pi yaSeṇiya-nivobhaṇai

448. ai-vallahattikāūṇaappiotujjhadeviohāro

khellaṇa-mettamimīesamappiyaṃsāvaroheṇa

449. eīepuṇṇehiṃkuṇḍala-vatthāṇiniggayāṇitti

kahamuddāliyaettoappeuṃtujjhajujjanti

450. sāCellaṇāpayampai punaravi jai majjha desi n’eyāṇi

tāmarihāminiveṇaṃbhaṇiyaṃkurutaṃjahājuttaṃ

451. nippaṇayaṃsoūṇaṃniva-vayaṇaṃCellaṇātaoruṭṭhā

uṭṭhāyacaḍaituṅgaṃpāsāya-gavakkhamegaṃtu

452. jāv’ appāṇaṃmuñcaitāv’ āyaṇṇaimiho-kahāheṭṭhā

Seyaṇaga-gayā’rohaga-tab-bhajjā-Magahaseṇāṇaṃ

453. uccāvaccaṃ vattaṃ eyāṇa suṇemi tāva pacchā' haṃ

jhampissāmi vicintiya avahāṇaṃ dei tattha ṭhiyā.

454. jampei Magahaseṇābhattāraṃ Māgahīebhāsāe

tīselakkhaṇameyaṃrephovabhaṇijjai la-kāro

455. etthanayalammivaṭṭaidāsīṇamahoċċhavotaokanta

Tahĩtā ’lamkaliyāodāsīoniyaya-vibhaveṇaṃ

456. ujjāṇammigamissantiteṇaSeyaṇagahatthiy’ābhalaṇaṃ(Magadhi)

campaga-mālaṃ me dehijeṇaahiyābhavāmiahaṃ

457. Seyaṇaga-gandha-kariṇohatth’āroheṇabhanna

esā u pāṇa-ppie pie mahaevaṃrūsainivo snūṇaṃ

458. lamme nala-nāli-saṃkuleLāyagihedāsī-maheihaṃ(Magadhi)

jai eyãna desi māliyaṃpiya-uċċhaṅgecayāmijīviyaṃ

459. naciraṃ thalammi macho jīvainaciraṃjalammiya

paiṭṭhojalaṇodippainaciraṃvajjaidadduraḍãsūla-ghāehiṃ

kimamhemārāviuṃicchasi

460. macchassajīviyavvaejalaṇassajāliyavvae(Magadhi)

daddulassavajjiyavvaecila’cila-kale dekkhiyavvae

461. ukkiṭṭha-vicitta-māliyaṃmuttāhala-āvaliya-ujjalaṃ (Magadhi)

jai ābhalaṇaṃnadehisipiya-uċċhaṅgecayāmijīviyaṃ

462. ai-tāṇiyaṃ ca tuṭṭai ḍāli ai-nāmiyā ya bhajjei

bhajjā hu duhayā sap-puriso kāuriso tti mannae

463. na savvaso tāṇiyaṃ ca tuṭṭai nāviya savvaso ḍāli bhajjai (Magadhi)

savvā vi na nāma duhayā sap-puriso kāuriso tti mannae

464. lamme nala-nāli-saṃkuleLāyagihedāsī-maheihaṃ (Magadhi)

jai eyãna desi māliyaṃpiya-uċċhaṅgecayāmijīviyaṃ

465. re raha-kāra kiṃ vihannasi eraṇḍayaṃ aīva nāmanti

bhajjai esā na namai iya pagai dud-duma-layāṇaṃ

466. na ya nāma-mitta-dūsie savv'-aṅgesu vi dūsiyavvae (Magadhi)

eraṇḍa-dume uvajujjae hohu na hāli ha kajja-jogae

467. lamme nala-nāli-saṃkuleLāyagihedāsī-maheihaṃ (Magadhi)

jai eyãna desi māliyaṃpiya-uċċhaṅgecayāmijīviyaṃ

468. ārāmiya kiṃ khijjasi limbaṃ siñcesi jaṃ tumaṃ evaṃ

kaḍuya-phalāṇi dāhi payaī dud-duma-layānaṃ sā

469. annattha aṇ-uvajujjumāṇae kiṃ annattha na hoi jogae (Magadhi)

nimba-phalammi dūsie osaha-kajjesu pauñjissae

470. lamme nala-nāli-saṃkuleLāyagihedāsī-maheihaṃ (Magadhi)

jai eyãna desi māliyaṃpiya-uċċhaṅgecayāmijīviyaṃ

471. pupph'āīṇī ya jassa bhakkhei vasei jassa nissāe

mūlāṇi tassa khaṇai ya sūyara-jāī ya erisagī

472. anne annassa colae se vi ya annaha bhaṇḍa-vālae (Magadhi)

na vi sūyala itti savvaso hoi dumāṇa viṇāsa-kālae

473. ukkiṭṭha-vicitta-māliyaṃmuttāhala-āvaliya-ujjalaṃ (Magadhi)

jai ābhalaṇaṃnadehisipiya-uċċhaṅgecayāmijīviyaṃ

474. hatthā’roheṇabhaṇiyaṃnūṇaṃ pie bhajja-sayāṇimajjhaṃ

eyaṃ ca sikkhaṃ jai nakaresialaddha-bhogāyatahamaresi

554. jai tāvaahaṃekkāmarāmitāSeṇiyassakiṃbhūyaṃ

hohīannāo vi yasantivarāobahūbhajjā

555. iyamaraṇaoniyattāgameikālaṃniya-suheṇaṃ

Bibliography

Alsdorf, Ludwig. ‘ZweiProben der Volksdichtungausdemalten Magadha.’ In Beiträge zur Indien forschung, edited by H. Härtel, 17–24. Berlin: Museums fürIndische Kunst, 1977.

Norman, Kenneth Roy. ‘Two Prakrit Versions of the Maṇipati-Carita. Edited by R. Williams. Pp. Xii 370. London: Published for the Royal Asiatic Society by Luzac and Co., Ltd., London, 1959. (James G. Forlong Fund Vol. XXVI.).’ Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 92, no. 1–-2 (1960): 91-92. Accessed August 24, 2020. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-the-royal-asiatic-society/article/two-prakrit-versions-of-the-manipaticarita-edited-by-r-williams-pp-xii-370-published-for-the-royal-asiatic-society-by-luzac-and-co-ltd-london-1959-james-g-forlong-fund-vol-xxvi/58298F26517AACB296579435C809B45B

Williams, Robert, ed. Two Prakrit versions of the Manịpati-Carita. London: Luzac & Company Ltd. for the Royal Asiatic Society, 1959.

Williams, Robert. ‘A critical edition of the Jaina Prakrit text Munịvaicariyaṃ.’ PhD thesis, Department of Indo-Aryan Languages, School of Oriental and African Studies, 1951.