I regard the theatre as the greatest of all art forms, the most immediate

way in which a human being can share with another the sense of

what it is to be a human being.

—Oscar Wilde

In the social structure of India, living traditions hold a prominent position. Any form of living tradition has the essential trait of moulding itself to remain relevant. They are, therefore, the registers of the cultural history of a community, its morals, needs and ethos. Since folk theatre form is an amalgamation of many living traditions, like songs, dance, music, poetry and art, it is the storehouse of local history and heritage, whose preservation is necessary.

Maach is a prominent folk theatre form of Madhya Pradesh and historical findings suggest that it has been an integral part of the local culture of the Malwa region since the early eighteenth century, making it a 200–250-year-old art form. Gopalji Guru of Bhagsipura, Ujjain, is touted to be the one who introduced maach in Madhya Pradesh; he eventually authored many maach plays himself. Traditionally, maach is performed around the Indian festival of Holi and it is also believed that maach originated to entertain the local communities as there was no other mode of entertainment available in those times.

It is believed that maach evolved from the khyal[1] folk theatre of Rajasthan, which is also believed to have given rise to nautanki in Uttar Pradesh and svang in Haryana. Another theory suggests that around the eighteenth and nineteenth century, turra kalangi[2] (a popular folk theatre form of Rajasthan which uses musical dialogues and poems to narrate popular folk tales and legends) troupes came with the Maratha forces to Central India and led to the beginning of maach, which gradually evolved into a staged performance with new stories, songs, dance and characters.

What is Maach?

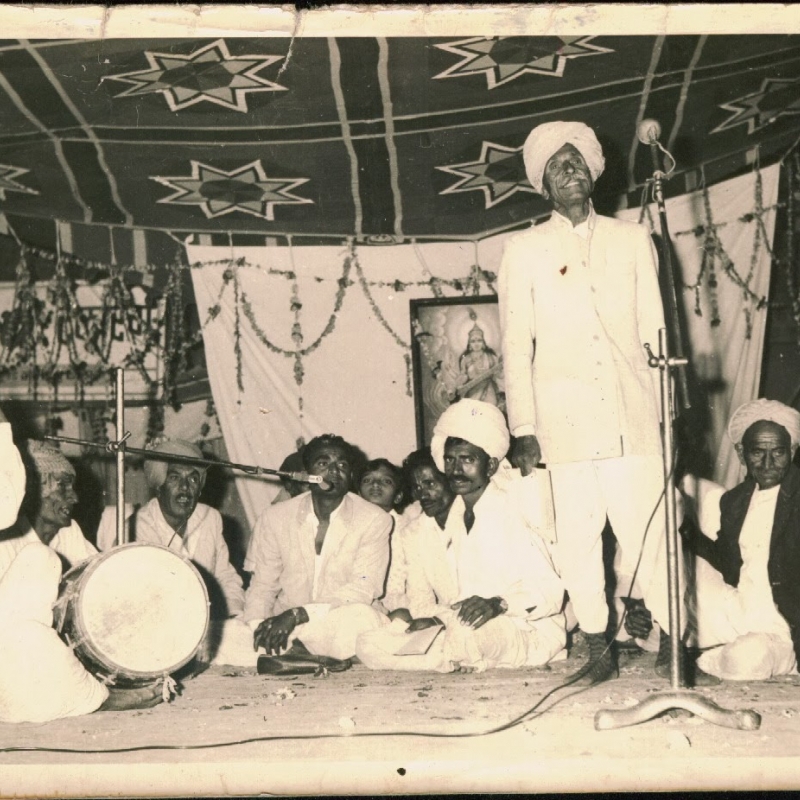

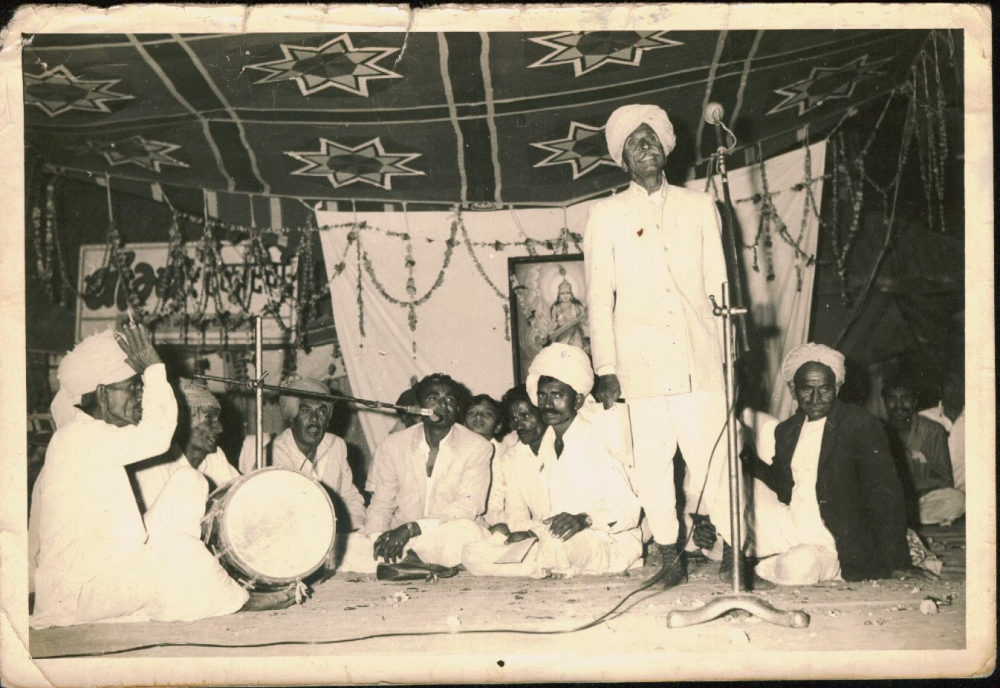

The term maach is a Malwi translation of the Hindi word manch (stage). Essentially, the term maach signifies two meanings, the stage itself and the play/performance. Maach is basically a musical play where a group of performers sing and dance along with dramatic representation of many mythological, religious and historical stories. It has over 150 manuscripts and more than 125 melodies, which are orchestrated around five to seven different rhythms. Maach is known to be performed in the open, in an intersection in the village, an open field or a villager’s courtyard. (Fig.1) It is performed and enjoyed as much in the towns of Malwa region as in small villages.

Maach is mainly performed by men who also perform the roles of the female characters. (Fig. 2) Maach artistes develop and rehearse the play in local community areas. Besides being good actors, they are also known to be noted singers as singing is an essential element of their performance. The plays are performed on an elevated manch; musicians are placed in the middle of the stage from where they play live music during the performance.

Rituals and Performance of Maach

A month before the day of the performance, a manak khamb (a wooden pole believed to eliminate bad omen) is established in the chosen area. Dholak is played, and all the performers of the group gather. The ritual involves singing prayers and distributing sacrament. The installation of manak khamb is a way of announcing in the village that a maach performance will take place in the area in a month’s time; it also alerts the performers of the village to start preparing for their performances. After the ritual of manak khamb, the process of building the stage starts almost immediately. It is important to note that the stage is more often than not built facing the north direction as it is considered auspicious; the practical reason was that in earlier times when there was no facility of speakers and mics, facing north ensured that the wind carried the voice of the performers far and wide for the audience.

Along with the manch another wooden platform is built in the upstage area where the experienced performers, singers, musicians sit along with the amateur performers and apprentices. As the performers sing their bol (dialogues), the choir repeats after them, and this practice of singing after the performer is called tek jhelna (giving support). This practice helps in repetition of the dialogue for the spectators and also enables the apprentices to learn the words. It prepares the new batch of maach performers, and since maach is a folk theatre based on singing, the choir emerges as one of the most important elements of the overnight performance.

The performance of maach starts at night and goes on till the early hours of the morning. The performers who earn their living through day jobs, finish up early and get ready to perform overnight. The spectators also start pouring in by late evening from nearby villages to enjoy the performance. Before the main act of maach, the performers sing songs, and there are short comic skits by Bhishti (the water-bearer), Farrasan (carpet spreader) and Nanak-Sai pande (monks of Nath community) that warm up the community spectators for what is to come. Bhishti, through his act, sprinkles water on the stage from his waterskin, which indicates purification of the stage. He then introduces himself, tells the audiences where he comes from, and his purpose.

He sings:

Bharwalo paani, chhaani ke laayaji samandar teer se,

Sone ki meri masak bani hai, kanchan dhol maddhaya.

Meri masak ka paani pi le, us ghar kar du maaya,

Kaasike pandit kahiye, jin ghar bharta paani,

Sab naari sukhi hoy, nar sun lo meri vaani.

Masakmaaye ka paani pilau, paapkate sab pelebhoka.

Koi mat nahao, Ganga-Gomti, koi mat dhyaan dharo Shiv ka.

(Fill your water-containers, I have bought the pure water of the ocean

My waterskin is made of gold and has golden carving,

Whoever drinks this water will prosper,

The pundit from Kashi says, consuming this water will make the women happy,

Listen carefully, men.

Drink this water and it will wash off all your past sins,

No need for dips in river Ganga, no need to pray to Lord Shiva)

Then comes the Farrasan, a female character played by a male performer. She introduces herself, wipes clean the floor during her act and spreads a carpet on the stage for the main act to begin. After their comic skits are over, all the performers come on the stage and sing and pay their respects to Lord Ganesha, Lord Bhairavnath, Goddess Durga, Lord Hanuman, and other gods and goddesses. Lord Bhairavnath is believed to be the creator of maach and without his blessings no maach performance can take place successfully. (Fig 3)

Features of Maach

Maach, through its stories, discusses the ideas of power, splendour, injustice, violence and social issues with the audience, which largely comprises farmers, with the help of relatable historical figures, and mythical and religious characters. It uses satire and humour as its tool to make pertinent social commentary.

Many of the historical themes are adopted from local legends, anecdotes of rulers and warriors, but several themes are also borrowed from Vedic Puranas, Hindu epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata. Most often, maach features tales of popular mythical and mystical characters of Malwa, like Damayanti, Nal, Gopichand, Prahlad, along with Tejaji and Kedar Singh who are prominent Malwan heroes.

Interestingly, as per the need, a character can be replaced and played by a different artiste from the one assigned. For instance, if the artiste playing the role of the king cannot continue for some reason, he can easily be replaced by the artiste who was playing a different role. It is a popular saying in Malwa that maach has more to do with listening than watching. Traditionally, the costume and stage properties for the maach performance was collected from within the community. Local community members came together to give their clothes and household items for the performance to take place successfully. It used to be a collective community effort, but today either the performers buy the costume or rent it out.

In maach, dialogues are called bol, rhyme in the narrative structure is known as vanag and the melodies of this folk theatre are called rangat. Being a musical theatre form, songs take precedence over dialogues. Besides having evocative verses, its immensely evolved and appealing theatrical musical structure makes maach performances opulent and attractive. It is important to highlight that maach borrows heavily from Indian classical music. One can notice the presence of many raags such as raag jaijaivanti, pilu, kalingada, Bhairavi, asavari, sorath, Sindhu, etc.; however, maach is particularly based on raag khamaj. Raag khamaj, usually performed at midnight, is a Hindustani classical raag and its melodic structure is known to be ideal to express both the emotions of separation and union.

As Indian classic music system assigns particular time of the day for particular raags, maach performances and their use of raags in them are timed accordingly. Since maach takes place overnight, the folk theatre form only includes raags that are to be sung after midnight or early morning. For instance, songs based on raag Bhairavi are placed at the end of the performance since the assigned time frame to perform this raag is in early hours of the morning.

Apart from Indian classical music, the musical structure of maach is also highly influenced by the folk songs sung in the Malwa region at different occasions like teej (a celebration of monsoon primarily by women) wedding, bidai (a wedding ritual where the bride bids farewell to her maternal family), haldi (a pre-wedding ritual for both bride and groom), Gangor puja (a celebration of spring, harvest, and child-bearing), etc. Maach performers ensure that melodies, rhymes, beats, words and tunes are composed in a manner that they depict a particular season or occasion on which that performance is based, hence music becomes the key element to unfold the narrative throughout the night. Maach mainly has three key instruments: dholak, sarangi and harmonium. (Fig. 4) The beats played on dholak during maach performances are mainly theka, thaap, chanchar, roopchandi, keharwa, rupak and dadra, which are the different taals or rhythmic beats as per the Indian classical music also known as the musical metre.

Future of Maach

Recently, maach has experienced a gradual shift in its focus. From telling religious and mythological stories, it has started indulging in contemporary social issues and ideas of development. For instance, new performances are discussing the poor state of the education system, dacoity, unemployment, unorganised labour, class division, etc.

Maach performers are trying to adjust to the changing times by telling new tales and bringing new perspectives to old stories. Malwa region holds maach very close to their heart and the akhaadas, seniors performers, local communities, theatre groups, and state organisations are constantly making efforts to revive it, but without a large-scale community and collective push, the road ahead looks difficult.

Notes

[1] Khyal folk theatre emerged in the eighteenth century and is one of the most prominent folk theatre forms of Rajasthan. It mainly tells mythological tales and ancient historical episodes. Khyal is performed for days following the festival of Holi.

[2] Turra kalangi is a popular folk theatre form where the story is performed through poetic and musical dialogues. Four hundred years back, this folk theatre was jointly formed by two saints of Mewar, Tukhangir and Shah Ali. Essentially, the performance of turra kalangi is known as dangal where two performers get into a poetic dialogue with each other which culminates in the early hours of dawn. Turra kalangi is most popular in Rajasthan and some parts of Madhya Pradesh.

Bibliography

Brandon, James, and Martin Banham. The Cambridge Guide to Asian Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Folklore Society. Folklore. London: General Publisher, 1981.

Kumar, Sanjana. ‘Maach is the Effective Platform of Malwa From Last 250 Years.’ Patrika News, Bhopal, September 1, 2016. Accessed December 7, 2019. https://www.patrika.com/bhopal-news/mach-is-the-effective-platform-of-malwa-from-last-250-year-1388304/

Mishra, Sunil. Malwa Ka Lok-Natya Maach. Bhopal: Adivasi Lok Kala Parishad, 2018.

Madhur, Shivkumar. Madhya Pradesh Ka Lok Natya Maach. Bhopal: Adivasi Lok Kala Parishad, 2000.

Rajpurohit, Bhagwatilal. ‘Maach ka Pradarshan.’ In Madhya Pradesh ka Lok NatyaMaach aur Anya Vidhaaye, edited by Dr Shailendra Kumar Sharma. Ujjain: Ankur Manch, 2006.

Sharma, Jagdishchandra. ‘Maach: Prerna Aur Udbhav.’ In Madhya Pradesh Ka Lok Natya Maach aur Anya Vidhaaye, edited by Dr Shailendra Kumar Sharma, 31-36. Ujjain: Ankur Manch, 2006.

Sharma, Manorama. Music Heritage of India. New Delhi: APH Publishing Corporation, 2007.