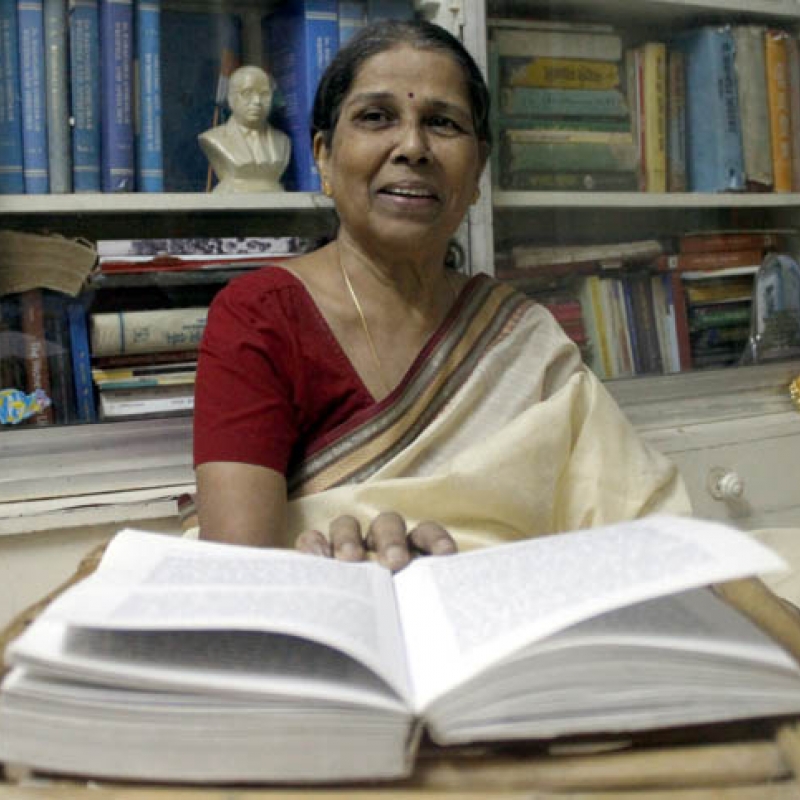

Urmila Pawar (b. 1945) belongs to the Mahar community and grew up in a small village near Ratnagiri in the Konkan area. Her father’s insistence on educating the children eventually led to Pawar’s moving to the city of Mumbai to study. She went on to become a prominent figure: an activist involved in the issues of caste and gender, an award-winning writer with a widely read autobiography, one of the most remarkable women from the Dalit literary movement who continues to raise the issues of caste/gender. Urmila Pawar wrote critically about the social realities of being a Dalit, and within that of being a woman. Her writing is self-reflective and makes the reader ponder over these intimately felt oppressions.

In order to begin to comprehend Dalit feminist writings, closely reading Pawar’s work is paramount to set up a historical context for the Dalit feminist movement in Maharashtra. Framed against such a background are Pawar’s works such as her short story collection, Chauthi Bhint, Sahav Bot, published by Sambodhi Prakashan, Mumbai (1990), or her autobiography, Aaydaan (2003), translated as The Weave of My Life: A Dalit Woman's Memoirs by Maya Pandit. Everyday feminist manifestations through her work of fiction makes the latter a critique of the oppressive social structures of caste and gender.

Origins of Dalit feminist writings in Maharashtra

One must see, at first sight, what does not let itself be seen. And this is invisibility itself. For what the first sight misses is the invisible. The flaw, the error of first sight is to see, and not to notice the invisible.

(Derrida, 'Spectres of Marx' New Left Review 205 (1994):31)

Dalit feminist writing in Maharashtra ushers in the so far ‘invisible’ category of the Dalit woman—she, who is at the lowest rung of the caste/gender hierarchy and who, till the 1980s, has been invisible, unrecognized and unheard. Until the 1980s, the autonomous women’s movement and the Dalit literary movement overlooked the issues faced by the Dalit women due to their position in the caste and gender hierarchy. This period marks the shift that sets in motion the Dalit women’s literary movement.

Dalit women’s voices were then, one could argue, their reaction at not being represented and being excluded from the autonomous women’s movement. It was an expression of their need to construct a certain modern feminist movement a reaction against the Dalit literary movement which was primarily masculine. The autonomous women’s movement, particularly in Maharashtra, in its struggle to liberate the woman, invented and appropriated narratives and symbols. The latter nominated the elite Marathi woman to represent all women, thus creating a homogenous category of ‘the woman’ without considering the position of this ‘woman’ in the hierarchy of either caste or class. This overt blindness towards the issues of women from the Dalit community and the lack of political will in both the (abovementioned) movements—the autonomous women’s movement and the Dalit literary movement—led to unity and mobilization of the Dalit women in the mid-1980s. A group of young Dalit feminists formed the ‘Mahila Sansad’ in Mumbai, Maharashtra. The latter shaped a forum by the name ‘Samvadini-Dalit StreeSahityaMaanch’, a literary platform to bring forth the narratives of Dalit women. This forum marks the early beginnings of the Dalit feminist literary movement which went on to become a platform for the diverse voices from within the communities to emerge and present the Dalit women’s standpoint.

This movement served to carve out a hitherto lacking space for Dalit women to write, and in doing so raised a whole lot of questions that had been left unasked. These questions, in turn, allowed for debates on homogenizing effects of Brahmanical concepts, Brahmanical norms in Indian feminism, the exclusionary politics of the Indian women’s movement and provided an impetus to reviving the Phule/Ambedkarite school of thought as the foremost feminist thought in the Indian context. Moreover this movement allowed a greater insight into the anti-Mandal agitations—that vehemently opposed the Mandal commission report, which recommended 27 per cent reservation for OBC candidates at all levels of government service—that embodied the links between caste and gender and the ever-present resultant interlocking oppressive systems, which is a recurrent theme in Phule’s work as well.

The Dalit writing acquired its rigour and got its distinct voice from the Dalit Panthers movement in the 1970s which brought into light the political and personal experiences of violence and oppression faced by the community. Baburao Bagul, Namdeo Dhasal, Anna Bhau Sathe and numerous other Dalit men comprised the Dalit leadership. However, the men ended up writing about women from the Dalit communities as sacrificing mothers and dutiful wives; but these accounts were merely fleeting references to the women. The structural and individual dimensions of gender were absent/forgotten because of this ‘male privilege’. The Dalit women’s writing is a dissenting voice against this feeling of being ‘left out’ or forgotten. Articulation of women’s questions related to their positions in caste, class, rural/ urban geographies, was at once political as well as cultural.

Women’s writings in Maharashtra, around 1950–75 predominantly consisted of autobiographies with narratives of middle-class Marathi women and their lives. Although this was an attempt to make space for women’s writings, it overlooked the fact that a large number of autobiographies were by women writers belonging to a certain (upper) class and (upper) caste. Needless to say, these narratives hardly ever mentioned caste, and in doing so were indicative of the lack of understanding on the part of the upper class, and of upper-caste feminists, about the issues and oppression faced by Dalit women. Thus inadequate representation or complete absence of cultural as well as political space became the ground on which the Dalit feminist movement made its early development. The coming up of several autonomous Dalit women’s organizations at regional as well as national levels, brought into light the historically invisible issues of lack of space, the inadequacy of language and the total absence of articulation of the ‘difference’ which was propagated because of un-interrogated social relations of caste and gender.

The Dalit women writers emerged from such historical trajectories which marked their work in a distinctive way; their narratives were more inclusive, incorporating diverse voices, in comparison with those of their male counterparts or of the autonomous, mainstream feminist movement. These narratives were, in a way, a process of retrieving the forgotten past. The fact that modern women’s narratives, including testimonials, memoirs and autobiographical writings, did not take into account the predicament of Dalit women and their history, requires that this history be retrieved. The history of Dalit women ought to be remembered and documented against the mainstream narrative which is invested in forgetting it. Dalit feminist writings are marked with protest, rigour and a distinct language with a marked overtone of caste. This is remarkable as a form of dissent by not sticking to Brahmanical, upper-caste ways of writing. These narratives of lives lived on margins are not so much about literariness; they are as much about the documentation of, and protest against, the continuous historical oppression the Dalit woman is subjected to, her will to speak differently and the issue of ‘denial’ of this difference by the mainstream women’s movement and that of their male counterparts alike. Modern feminism had forgotten caste; but Dalit feminism invoked the memory to bring forth narratives symptomatic of how caste, class, and gender are interlocked categories and not independent of each other. It brought forth the question as to whether the Dalit and the upper caste woman were equally situated in the social context. To begin to answer this, it was important to take into account subjective experience not just as individual stories but as counternarratives to the dominant discourse. In writing objectively about the phenomenon of caste, the upper caste inadvertently hides the structure that allows for the practices of casteism to continue. Gendered subjectivity in caste narratives brings forth the nuances required to deal with an issue as complex as caste which is at once cultural as well as political.

The inseparability of caste-gender identities questioning the singular category of Dalits which the predominantly male Dalit literature presented through their autobiographies, poetry and other works, was possible with the dawn of Dalit women’s writings. The privately lived struggles by women were equally important for the anti-caste struggle to truly question and begin to change the realities of the people of the Dalit community, men, and women alike.

It is important to note the cultural shift these narratives brought into the Marathi literary sphere. Which work gets termed as literature? The politics of prioritization of the publication of certain works over others, the forming of the literary canons, and the obvious dominance in terms of Brahmanical linguistic practices, were called out and questioned with these writings. This work also invited reflection for the academic and pedagogical practices that ended up ‘adding and stirring’ caste in one of the modules, thus suggesting reconsideration of the practice of teaching about caste in our institutions. The Dalit woman and her writings shook the Marathi public sphere; her language was strong and she did not shy away from talking about the most intimate of her experiences. These experiences were relational with caste and gender, and hence crucial for understanding gender and caste realities.

Locating Pawar’s work within the diverse canon of Dalit women’s writings

The reader, however, needs to understand that ‘Dalit women’ are not so much a homogenous category in themselves; their writings are diverse, marked by distinct geographical, cultural and political periods. These ‘Dalit women’ do not form a unitary category as Rege (2006) points out. But these narratives give a significant historical insight into the different interpretations of society and life lived on the margins of caste and gender. Even within a particular region, for instance, Maharashtra, the writings have a distinct quality depending on the political ideology of the region, the geography a particular writer is a part of, and her political standpoint. However, the influence of Phule’s/Ambedkar’s thoughts remains a constant thread in all writings whether it is ‘Babytai Kamble’ in her seminal work Prisons We Broke (1986), or ‘Shantabai Kamble’ in the kaleidoscopic Story of My Life (1988) talking about Dalit women’s issues. Both of them from western Maharashtra and the pre-Ambedkar era provide a lot of insights into the early emergence of the Ambedkarite movement. For us- These Nights and Days (1990) by Shantabai Dani and Closed Doors (1983) by MuktaSarvagodalso reveal the tussle between Gandhian and Ambedkarite politics. Furthermore, Kumud Pawde who argued for these writings being critical narratives, wrote Thoughtful Outburst (1981) underlining the double exploitation faced by women, as labour and as members of the Mahar community. However, she also talks about the strengths of the Ambedkarite movement. Her work reflected women’s movements, the idea of class amongstDalit women, inter-caste marriages and many such issues critical to the politics of caste and gender. Pawar’s work emerges after the time when these women have set in motion a movement of articulating issues that had never been heard of, or been written about with the testimony titled The Weave of Bamboo (2003). Pawar emerges as one of the vital voices to take the Dalit women’s writings even further by mapping the strenuous relationship of Dalit feminism and different social movements in Maharashtra. Pawar, along with Meenakshi Moon, is well known for her work AmihiItihas Ghadavla translated into English as We Also Made History by Wandana Sonalkar. It is a book on Dalit women's participation in the historical anti-caste movement (Dalit movement) led by Dr B.R. Ambedkar. It makes one of the greatest contributions to understanding and fighting the forgetting of Dalit women’s participation in the Ambedkarite movement. Pawar also wrote a lot of fiction in the form of short stories, and her work, both autobiographical as well as fictional, provides greater insights into the caste/gender realities of Maharashtra. Pawar’s work is a response to the blatant de-politicisation of the Dalit women’s place in the system, not just to map historical account but to talk about it here and now, the newer forms that the system of caste operates under.

Righting (through the medium of writing) the historical wrongs

Pawar’s fiction is a way to construct a meaning, a cultural discourse different from, and outside of, the dominant culture by articulating the unspoken. Though Marathi Dalit literature is generally characterized by anger and revolt, Pawar's writing is not necessarily marked by an upfront protest and anger. Her texts are not necessarily shaped by the conventions and tradition of Marathi writing which is culturally dominated by the upper-caste, Brahmanical narratives of storytelling and language. Her work has raw usage of language, as is spoken within the community, thus making it illustrative of the voice absent in the Marathi mainstream literary canon for too long. The writings are truly representational of the context, the geographical, social and material reality of everyday life that produces and reproduces experiences of caste and gender subordination. Fiction so intimately based on lived experiences, assumes more importance, transcends the requirements of literariness of a story and becomes a way of theorizing the subjective experience. These are not mere fictional stories but contain the content of the experiences which varies depending on the location. The content is closely related to the absence of any choice given to these women as a part of the patriarchal structure. The short stories, however, are not just limited to recording the context and content of the experience by featuring the women protagonists through different urban and rural locations, age and the socio-economic context; it takes a step further into imagining how these women within the Dalit community, situated differently, would dissent and subvert the structure.

In order to understand any form of social oppression, it is crucial that those being subjected to this oppression be heard. Dalit feminist writings by Pawar create that space for articulating the experience of being a subject of gender and caste in the Indian society. It is important that these stories are heard.

‘For those of us who still have circumstances’—Margaret Atwood

Short stories weaved by Pawar are about the circumstances Dalit women find themselves in and how they navigate these oppressive situations. Fictional narrative allows the reader to look at the experience of gender and caste from a necessary distance and thus helps theorize the structural violence. What this does is, allows for self-reflection on the part of the reader as to how s/he embodies caste and cultural practices that reproduce the structure of caste and gender. This helps bring both reason and emotion together to understand the lives of these women lived on the margins. It is not about distributing blame and shaming the non-experiencers, but about sharing suffering and making it relatable and understandable for those who haven’t experienced these particular oppressions.

Pawar’s protagonists are women we meet every day. The woman selling vegetables on the footpath near your house, the woman you share your bus seat with to office, your neighbor or someone you have known for years but never bothered to enquire or look beyond that which is apparent. Protagonists sometimes completely overthrow the patriarchal structure and sometimes mend and bend it in ways to work around them. Women are portrayed as being stoic; they voice dissent and show a heightened awareness of their position as they constantly try to mitigate the inescapable subordination. For example, in the case of Vegli (Odd One) Nalini, the protagonist is seen to be acutely aware of her position. She is, as the title depicts always the ‘other’ everywhere; in office, amongst her in-laws, in her locality. She can change her life by shifting from chawl to the new house; in doing so she aspires to move away from historical markers of identity and create a new one for her family. She works in a government office where she has to hear about how ‘Dalits...have it good...the government pampers them’ (57). The writing style is lucid and beautifully elucidates on the material realities that become the markers of identity for caste; for instance, women in the chawl call out to Nalini ‘Here comes the schoolmistress’, ‘Look at her petticoat shine!’, ‘What’s the point of all that education, after all, you too have to blow on the cooking fires to keep them lit’ (Pawar 61).Nalini, after getting a government quarter is determined to move out; and her husband assures her that he would persuade his parents. Eventually, her husband gives in to his mother’s persuasion in spite of his desire to shift with Nalini. But the climax of the story is astonishing when we see Nalini pick up her baby and leave, not waiting to persuade anyone or seek approval. This act of walking away without waiting for her husband’s answer knowing that he has already given in to his mother’s pressure is both a stoic acceptance of reality as well as a stubbornness to overcome it and act. This act is a bold response to the patriarchal domination Nalini is faced with.

In the story titled 'Nyaya' (Justice), Paru the central character, who is a young widow, had been assaulted and is now pregnant. She insists on keeping this child while the entire village is convinced that she should abort it. Interestingly this story is narrated by a male character who belongs to the village where Paru is from but presently lives in the city. He is in the village on account of a business and throughout the narration makes it evident to the reader that he considers himself different from the villagers, progressive to their regressive ways of living. Pawar writes the story in a way that Paru is presented to the reader through the male narrator’s gaze. It is interesting to note how the male gaze looks at this particular issue of assault of a woman, how it interprets the woman wanting to keep the child and in doing so allows us to look at the skewed power dynamics of gender and caste in a rural setting. Paru is very well aware of her position as a widow and looks at this child as someone who belongs to her—someone she can bring up on her own without a man to support her. She acknowledges that she was assaulted but now what she seeks is choice to decide about the baby’s fate; this is an important question articulated by means of questioning women’s agency over their bodies; in doing so she seeks justice. Her ways of seeking justice are different, she doesn’t want the perpetrator to be held accountable, she doesn’t want him punished, it is again symptomatic of the acute sense of awareness of her position and the power dynamics that are constantly at play. What she wants, however, is the right over her body, the right to birth this child and bring it up as her own. She doesn’t think she needs a man to bring up a child and here is where Pawar makes the narrator reflect on his privilege and his covert sexist understanding of Paru’s demands. We see him correcting himself, reflecting on his biases. We see in the story Paru voicing her opinion and keeping the child ‘This child is mine and I want it. I’ll raise the child myself’ (38). Paru questions the village authority firmly, she seeks justice of a different kind and she is fearless in making these demands. Incidentally, Pawar’s autobiography has such an episode mentioned with a rather sad outcome where the village women kick the woman on the belly to abort her child. The act of the women kicking her womb is symptomatic of the lack of right over one’s body; in the short story, Pawar imagines a different ending, albeit one where the woman decides and no one else decides on her behalf.

Another story worth mentioning is 'Cheed' (Anger)—it is a story of female friendships.Its theme is generally not dealt with in mainstream writing; anyone who has always wondered about how female friendships change once the husband enters the bond that had been earlier shared by only two people would find this relatable. It also in a way, questions the social structure which makes a vertical hierarchy out of our personal relations and whereby the husband is on a pedestal. This story also raises the issue about the norms that are expected from women to accept their husbands’ opinion as the right one without asserting their (own) thoughts. This story is layered and also talks about the woman’s agency and how every time she meets her husband she changes her opinion and adapts to his. The socialization of women to accept the husband as someone more knowledgeable, someone to look up to, instead of someone equal, is dealt with in this short story.

In another short story titled 'Sixth Finger', Pawar critically looks at the institution of marriage and the way a wife is tried and tested throughout her life. Her allegiance to her husband, how a husband has all the right to suspect his wife but a wife can never question the husband; this tale is an account of the ways in which the institution of marriage controls women. Sneha’s husband, Umesh, meets with an accident whereby the doctors inform the couple that there are fewer chances of Umesh becoming a father. However, Sneha conceives and her husband suspects it is the neighbour’s child and that she has cheated on him. When the child is born it also has a sixth finger like Umesh, but unfortunately, Sneha dies in the process of giving birth to the child. This story has no mention of markers of caste and in doing so Pawar claims rightly that this is a problem across castes, a problem of gender, and the institution of marriage.

Reading her autobiography, the title itself is suggestive of the centrality her mother plays in this entire struggle; she compares the entire process of writing to the weaving of bamboo baskets by her mother as a metaphor of the resistance.

Her short stories are well within the realm of her own life or experiences encountered by people close to her. One understands this while reading Aaydan and the short stories and recalling the incidents depicted in both her works. While the autobiography represents and reflects on experiences, her fictional work goes a step further and imagines these significant occurrences which had left an impression on Pawar in her life, in different ways. For instance, the stoic, silent and persistent mother in Aaye (Mother) is a character modeled after her own mother, the one we are introduced to in her autobiography. The short story is a classic example of what the death of the patriarch does to a family in a patriarchal system. The woman is not deemed fit to decide for her family. The mother continues to work on the basket weaving to sustain her family; the only thing on her mind is to educate all her children, the promise her husband takes from her on his deathbed. She is slender, a bit bent and has a worn-out expression on her face but nevertheless, her hands constantly work on the weaving of the bamboo baskets. The similarities between the autobiographical account of Pawar’s mother and this character are bare. One cannot help but notice these stories sprouting from her lived experiences. Pawar’s work proves that it is not necessary to access an objective approach to issues of caste, class, and gender by staying outside our experiences; on the contrary, our experiences can be worth building cultural knowledge about the society. The mutual influence of autobiography and her fiction are evident. Later in the module, attempts are made to understand this very interconnectedness of Pawar’s fiction and her autobiographical writings in depth.

It is important that her stories are not just passively read as literature but as stories of social change and protest. To engage with these stories which in a way produce and reproduce structures is to sometimes imagine outcomes different from the given ones. At other times the stories are just a straightforward telling of the trials faced by Dalit women in their particular settings, and to reflect on the questions raised for the reader within the limited structure of a short story.

Above all, Pawar’s work breaks the rules of writing, uses raw and provocative language, and sketches characters that rebel and navigate within everyday mundane life. Her work invites the readers to look into manifestations of everyday feminism through the strange rebellious acts of her protagonists. It is an important revelation and a probing into manifestations of everyday, more inclusive feminism.