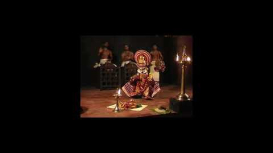

The classical theatre of Kerala, Kūṭiyāṭṭam—literally, “acting together”—survived for many centuries in the major Kerala temples, each of which had an acting space, kūttampalam, for these performances by the Cākyār and Nambyār artists, the guardians of this complex and ravishing art. Pilgrims and temple servants could stop in to watch for an hour or two, or a week or two, of live performances; and the deity of the temple was himself a prime spectator who was also allowed to choose the play he wanted to see. The door to his inner sanctuary was left open, with a direct view of the kūttampalam. The performance text was and remains in Sanskrit, though Malayalam is also present both in the Āṭṭaprakāram handbooks for performance that have come down in the families and in the roles of the Vidūṣaka clown and the highly unusual character of Śūrpaṇakhā.

Kūṭiyāṭṭam is often said to be a slow art form, though an attuned spectator may find it action packed, on many levels, and hence actually rather fast-paced. The shortest full performance is the twelve-hour version of Mattavilāsam (included in the videos here), played over three consecutive days. The longest is Mantrāṅkam, that is, the third act of the Pratijñāyaugandharāyaṇam attributed (wrongly) to Bhāsa; a complete rendition of this play takes some forty-one days. Note that the unit of performance in Kūṭiyāṭṭam is always the individual act, selected in most case from a much longer, multi-act play. Moreover, these individual acts are performed with a non-linear structural logic, never in the standard narrative progression of the Sanskrit text. The main units are the “Entrance to the Stage”, puṟappāṭu, on the opening night; the nirvāhaṇam retrospective, in which the Story-teller, guised as the main character, takes us back in time to help us understand everything that went into creating the situation of the dramatic present, and all the contents of the character’s mind; and kūţiyāṭṭam in the narrow and specific meaning of the term, in which there is more than a single character on stage (and the act builds toward a climax that usually follows the final bits of the Sanskrit text). Along with this innovative dramatic structure, which bears no resemblance to the classical notion of plot, itivṛtta, as we find it in the Nāṭyaśāstra, the Cākyārs adopt the technique of pakarṇṇāṭṭam, ‘alternating acting’, in which an actor, guised as a particular character, can present other, discrete, embedded personae, signaling the transition by untying and retying the poynakam sash that he wears around his waist.

The video segments in this module offer extended moments of performance from plays documented by the Hebrew University and Tübingen University teams, beginning in 2008 and continuing up to 2019. Many of the clips come from performances by the Nepathya troupe, led by Margi Madhu, in Mūḻikkuḷam. The Mattavilāsam performances were documented in Kiḷḷimaṅgalam with Kalamandalam Rama Cākyār in the lead role. Each video is introduced by the details of time and place and the names of the major actors. For interpretations of these performance segments, the reader-spectator is referred to David Shulman, The Rite of Seeing (Primus Books, 2020).