In the year 1579, Thomas Stephens (1549–1619), a young Jesuit priest, landed on the shores of Goa with the aim of preaching Christianity to the local subjects of the Portuguese colony. Little did he know that in the next four decades he would transform into a ‘devotee of the Marathi language’[1], composing Christian poetry in the style of the saint-poets of the region. Stephens is well known for his magnum opus Kristapurana, a poetic retelling of the Christian Bible in Marathi. Kristapurana may be read as one of the first retellings of the biblical narrative into a South Asian language. In his composition, Stephens retells biblical episodes to the neo-converts of Goa, giving the Christian story a distinct local interpretation. He begins, like his contemporaries, by paying tribute to the Marathi language:

|

Zaissy harallamazi ratnaquilla Qui ratnã mazi hira nilla Taissy bhassã mazi choqhalla Bhassa Maratthy

Zaissy puspã mazi puspa mogary Qui parimallã mazi casturi Taissy bhassã mazi saziry Maratthiya

(Kristapurana 1.1. 121–123)[2] |

Like gems among stones, Or a blue jewel among gems, Among languages, luminous, Is the language Marathi

As the mogra among flowers Or musk among perfumes So beautiful among languages Is Marathi

(Translation mine)

|

These are lines one would scarcely expect while reading a seventeenth-century missionary composition. In these lines, the Marathi language is compared by the poet to the mogra (jasmine) among flowers and to kasturi (musk) among perfumes. This was in the tradition of the saint-poets of the Marathi language.[3]

Catholic missionaries, specifically Jesuits, composed several works in the languages of the regions that were their mission fields. Translation of the Bible, however, was not one of the priorities of these early missionaries. Their works were largely catechisms, lives of saints and other poetic pieces and commentaries to familiarise converts with Church culture. In this period, Kristapurana is a rare sighting of an attempt to translate the entire biblical story into a South Asian language.

Kristapurana was originally published under the title Discurso Sobre a Vinda de Jesu Christo Nosso Salvador ao Mundo in Rachol, Goa, in the year 1616. According to A.K. Priolkar (1895–1973), Stephens’s ‘claim to a place among the immortals of the Marathi literature’ is because of this ‘classical presentation of the Biblical story in Marathi verse.’[4] Kristapurana is a grand poetic telling of the biblical story from the creation up until the resurrection and ascension of Christ. Stephens described his composition as a ‘Purana’. Puranas were originally Sanskrit texts, held in reverence by various sects of Hindus in the Indian subcontinent. In the period between 1000 CE and 1500 CE, these Sanskrit texts began to travel to the regional languages of the subcontinent through translations, including Marathi.[5] Marathi literary scholars place Kristapurana in this tradition of Marathi Puranas.

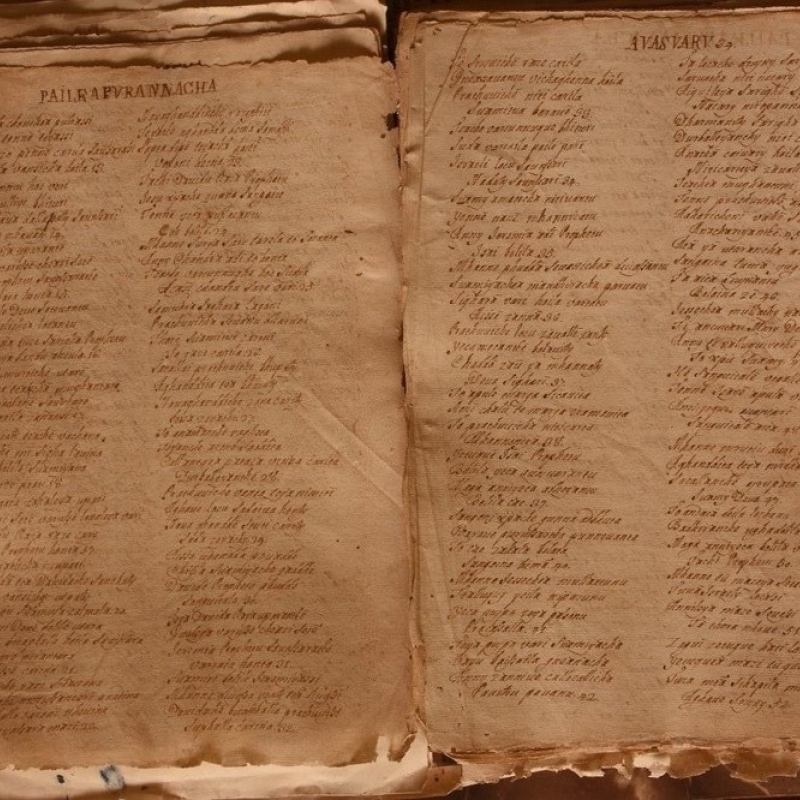

Kristapurana is composed in verse in the Puranic style. It has a total of 10,962 strophes (ovi). There are 36 cantos (avaswaru) in the Paillem Puranna (first Purana) and 59 cantos in the Dussarem Puranna (second Purana). The Paillem Puranna roughly corresponds to the passages of the Old Testament and the Dussarem Puranna to the New Testament of the Christian Bible.

The Poet and His Composition

Thomas Stephens was born in Bushton in the diocese of Salisbury in Wiltshire, England, in the year 1549. His father, Thomas Stephens (spelt Stevens in some sources), was a well-to-do merchant in London. His mother’s name was Jane and he had a brother Richard, who taught Theology at the Douay Seminary in France. Limited information is available on Stephens’s boyhood and education.

On April 4, 1579, soon after his priestly education in Rome, Stephens boarded a ship called the S. Lorenzo and set sail for India.[6] Further information of this six-month-long journey may be derived from a letter that Stephens wrote to his father, dated November 10, 1579, where he described the journey as perilous. People on the ship fell into ‘sundry diseases’ such as swellings and fevers.[7] It is understood from Stephens’s letter that close to 150 people on the S. Lorenzo were affected by these diseases. The ship reached Goa on October 24, 1579.

In Goa, Stephens was known by various names given by the Portuguese and used by the locals. His Kristapurana is published under the Portuguese version of his name, Thomas Estevao. Apart from a short period between the years 1611–12, which he spent in Bassein[8], Stephens spent the rest of his life in Goa doing missionary work. It may be understood from church records that Stephens had begun to learn the language and use it in church affairs soon after his arrival in Goa.[9] He was the only Englishman in the Portuguese colony, given a majority of his fellow Jesuits hailed from other European nationalities.

Stephens assumed responsibility as the rector of Patriarchal Seminary in Rachol in the year 1609. In a letter to his superior written in the year 1608, Stephens mentioned that construction work of the seminary buildings had to be stopped because of lack of funds. It may be understood from this that Stephens was actively involved in mission work in the region before he was appointed rector of the college. The original buildings of Rachol seminary, built during Stephens’s times, stand even today.[10] Stephens’s magnum opus was printed in the printing press housed in this college, marking a symbolic moment in the history of the printing press in India and the literary history of the subcontinent.[11] However, the only traces of Stephens that remain in this seminary are a picture of him (a modern artist’s imagination) on the wall of the library and copies of modern editions of Kristapurana. No original printed copy of Kristapurana is known to be extant today.

Stephens died in 1619 in Goa, three years after the publication of his magnum opus. He breathed his last in the Professed House adjoining the Basilica of Bom Jesus in Old Goa. According to Saldanha, he was ‘probably’ buried at the Rachol seminary. In spite of the scarcity of information about the life of Stephens in England and in Goa, his legacy lives on in the land he called his mission field. The Thomas Stephens Konknni Kendr is an institution run by Jesuits and is dedicated to the study of Konkani language and culture. It is named after Stephens in honour of his Arte da Lingua Canarim, which is considered the first grammar of the Konkani language, and for his services to Konkani.

The story of the press in which Kristapurana was printed is itself noteworthy in understanding the relationship between power, print technology, and the routes by which knowledge was produced and disseminated. A.K. Priolkar, in his work The Printing Press in India: Its Beginnings and Early Development (1958), retraces the development of print technology in India. Though there were earlier requests from Goan missionaries for a printing press, the printing press that eventually arrived in Goa on September 6, 1556, was the result of ‘a happy accident’.[12] A printing press which was meant to be sent to Ethiopia happened to land in Goa.[13] As a result of this, when Stephens arrived in Goa in the year 1579, a fully functional printing press existed in the region.

The first book that was printed in this press was Francis Xavier’s Doutrina Christa, in the year 1557. Stephens’s Kristapurana was one of the earliest works to be printed in this press. In addition to the letters of Stephens, there are three existing known works attributed to him. According to Priolkar, all three of them were printed in this press:

- Arte da Lingua Canarim: A Grammar of the Konkani language written in Portuguese. According to Saldanha, at present its only value is bibliographical.[14] Nevertheless, it is accepted to be the first grammar of the language ever written. It is believed to have first circulated in the handwritten form, and was probably used by missionaries attempting to learn Konkani. Priolkar notes that the grammar was written and used before Kristapurana even though it came into print only later. In 1640, Father Diogo Ribeiro S.J. edited it and got it printed at Rachol. Priolkar writes that a copy of the first edition can be found in the National Library of Lisbon. In his grammar, Stephens discusses the orthography, phonology, morphology and syntax of Konkani.

- Doutrina Christa em Lingua Bramana Canarim: This was a translation of the Portuguese catechism written by Padre Marcos Jorge. It was published after Stephens’s death, in 1622. Priolkar notes that this catechism, too, was written and used before Kristapurana, but came into print only in 1622.[15] Copies of this catechism may be found in Lisbon and Rome.

- Kristapurana: The original name of Kristapurana is Discurso Sobre a Vinda de Jesu Christo Nosso Salvador ao Mundo or ‘Treatise on the coming of Jesus Christ the Redeemer into the World’. It was printed in Rachol in the year 1616. Among all of Stephens’s works, this is considered the magnum opus.

The first two works of Stephens were in keeping with the Jesuit tradition of translating church culture into regional languages. But Kristapurana sets Stephens apart from his predecessors and contemporaries by its literary beauty and magnitude.

Until the Portuguese ban on using regional languages and texts in the year 1684, Stephens’s text seems to have enjoyed the appreciation of his fellow priests of the Catholic fold. Saldanha, in the introduction to his 1907 edition of Kristapurana writes that it was ‘held in great esteem especially by the middle and the lower classes of the Roman Catholics in the Konkan’.[16] It was probably read out on Sundays and during other devotions. Saldanha also notes that it was read during a ceremony called soti (shasti-pujan), conducted six days after a child’s birth.[17] He mentions that Kristapurana was found among the Christians of Mangalore. When 60,000 Catholics were imprisoned by Tipu Sultan at Seringapatam (1784–99), they seem to have sung verses of Kristapurana for solace and strength.[18]

Structure and Language

In the four centuries following its publication, Kristapurana has been read as a part of both Marathi and Konkani literary-historical traditions. The nineteenth-century scholar J.H. da Cunha Rivara in his essay ‘An Historical Essay on the Konkani Language’ (1856) lists it as a work of Konkani literature. Other historians of Konkani have followed suit, including a recent example such as Manohararaya Saradesaya’s A History of Konkani literature: from 1500 to 1992 (2000). Marathi literary histories stake equal claim to Kristapurana. S.G. Tulpule and Malshe count Stephens among the ‘Marathi purankaars’ of medieval Maharashtra.

According to the introduction written by Stephens, he intended to write his poetic work in Marathi:

He sarua Maratthiye bhassena lihile ahe. Hea dessinchea bhassabhitura hy bhassa paramesuarachea vastu niropunssi yogueaissy dissaly …[19]

(All this is written using the Marathi language. Of all the languages of this land, this language seemed worthy to convey the things of God…)

However, it is necessary to note that the text also contains several words from Konkani, Portuguese and Latin, reflecting the complex linguistic scene of seventeenth-century Goa.

The metre used in Kristapurana is the ‘ovi’. An ovi is a stanza consisting of four lines, the first three of which rhyme together, there being an occasional repetition of the rhyme somewhere in the fourth line, though this is by no means of its essence.[20] This was the metre used by the poets of the region, a large volume of Bhakti[21] poetry being in this metre.

These are the opening lines of Kristapurana praising the creator in the ovi metre. The ‘Christian’ God is invoked here in a style distinct to that of the Marathi saint-poets of the period.

|

Vo namo visuabharita Deua Bapa sarua samaratha Paramesuara sateuanta Suarga prathuuichea rachannara

Tũ ridhy sidhicha dataruCrupanidhy carunnacaru Tũ sarua suqhacha sagharu Adi antu natodde

(Kristapurana 1.1.1, 2) |

Hail omnipresent God Father God, Almighty True God Creator of heaven and earth

You are the bestower of virtue and prosperity Fount of grace, compassionate You, ocean of all joy You have no beginning, no end[22]

|

In the year 1925, Justin E. Abbott wrote a letter to the Times of India announcing his finding of the ‘Marsden Purana’ at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), which housed the collection of the English orientalist and linguist William Mardsen. The manuscripts tilted the ‘Adi Purana’ and ‘Deva Purana’ are handwritten renditions of Kristapurana in Devanagari script. Abbot’s letter reveals that he had also come across the 1907 edition of Kristapurana edited by J.L. Saldanha. However, when he saw the Devnagiri handwritten Purana in London, he assumed that it was the ‘original’, after a ‘hasty examination’.[23] The argument he proposed was that the Marsden version was written in ‘far purer Marathi’ and used ‘very little of the Konkani elements in words and idioms’. It also uses ‘dignified Sanskrit formation’.[24] For Abbot, this was evidence of the fact that the Marsden version is the original written by Stephens. A reading of Kristapurana itself and an analysis of the sociopolitical background during Stephens’s time, however, proves otherwise. Stephens himself clarified in the prose introduction to Kristapurana that he had written the text in the Marathi language and mixed it with Konkani in order to make it comprehensible to the local people living in Goa:

… pannasudha Maratthy madhima locassi nacelle deqhune, hea purannacha phallu bahuta zananssi suphalu hounsi, caequele, maguilea cauesuaranchi bahuteque aughadde utare sanddunu sampucheya cauesuaranchiye ritupramanne anniyeque sompi brahmannanche bhassechi utare tthai tthai missarita carunu cauita sompe quele.[25]

(… but seeing that common people do not understand pure Marathi, and so that the fruits of this Puranna may be enjoyed by many, I have left out many difficult words of the past great poets, and like poets writing in the present, have replaced them with simpler words of the Brahmana language at different places, to make the poem simple). (Translated by the author)

Stephens clearly mentioned his intention to make the poem simple, for the locals to understand it. Konkani was spoken in Goa, but Marathi was the literary language. Stephens mixed Konkani words with his Marathi, probably with a view to reach a wider audience among those who were not literate and could not understand literary Marathi. It is unlikely, therefore, that he would have used Sanskrit, as it would have made it even more difficult for the natives of Goa to understand it. Proselytising religions have to use popular languages (lokbhasha) and not ‘official’ ones, to appeal to the most basic religious beliefs that exist in a culture.[26] Unlike the languages of administration, the language of proselytation, of converting an individual from an entire religion and its tradition to a new religion, had to be a language that was close to the hearts of the people.

The terms that appear in Portuguese/Latin in Saldanha’s version and are Sanskritised in the Marsden copy are related to liturgy and church doctrine. Some of the terms that are Sanskritised in the Marsden Purana are as follows:

1. (1.1.37) Cruci – Siluvi

2. (1.1.38) Bautismu – Jnanasnana

3. (1.10.25) Patriarch – Mahapurusha

Caridade Drago has provided a line-by-line comparison with the Marsden Purana as an appendix to his edition of Kristapurana.[27] The Marsden Purana also leaves out an entire canto, ‘Avaswaru 22’ of the Dussarem Puranna. This is the avaswaru that relates the miracle of Jesus turning water into wine. The origins of the Marsden Purana remain unknown until now. Amonkar writes that Simao Gomes (1647–1722) could be the author of this version. Gomes also composed another well-known text titled Sarveshvaracha Dnyanopadesha.

Manuscripts and Translations

There seems to be a marked ‘invisibility and fragmentation’ while pursuing an archival study of Kristapurana.[28] Printed copies of the work from the seventeenth century are not known to exist, in spite of the fact that Rachol seminary where it was printed still stands in Goa in its original form. Handwritten manuscripts of Kristapurana can be seen in Krishnadas Shama Goa State Central Library and Goa University Library in Panaji. It is from the licenses copied out in these manuscripts that we get information about the date of its publication and reprints. All subsequent editions of Kristapurana have reprinted these licences.

Following are the manuscripts extant today:

- The Krishnadas Shama Goa State Central Library Manuscript: The title page reads: Discurso sobre a vinda de Jesu Christo Nosso Salvador ao Mundo dividido em dous tratados feito pelo Padre Thomas Estevão Ingrez da Companhia de Jesus. Impresso em Goa com licenca das Inquisicão, e Ordinario no Collegio de S. Paulo novo de Companhia de Jesu. Anno de 1654, Escripto por Manoel Salvador Rebello, Natural de Margão no Anno 1767.

- The Bhaugun Kamat Vagh Manuscript in the Pissurlencar Collection at the Goa University Librar, Panaji.

- The Pilar Manuscript, at the Museum of the Pilar Monastery, Pilar, Goa.

- The M.C. Saldanha Manuscript at the Thomas Stephens Konknni Kendr, Alto Porvorim, Goa. It is quite possible that this is one of the five manuscripts used by J.L. Saldanha in the preparation of his 1907 edition of Kristapurana.

- Manuscript at Thomas Stephens Konknni Kendr.

- A Manuscript of the work written in Devanagari script is preserved at the library of SOAS in the Marsden Collection. It is known as the Marsden copy.

The Pilar MS and the manuscripts at Thomas Stephens Konknni Kendr are now available in digitised format as a part of the British Library’s Endangered Archives Project. This digitisation project of Goan books ‘Creating a Digital Archive of Indian Christian Manuscripts (EAP636)’ has been led by Ananya Chakravarti. Digitisation of Goan texts from Stephens’s time is a significant contribution to the study of Christian writings from South Asia.

In the year 1907, J.L. Saldanha brought out a printed Kristapurana in Roman script from the handwritten manuscripts which were available. Saldanha’s edition, The Christian Puranna of Father Thomas Stephens of the Society of Jesus, is the first modern printed edition of the text. This version has been used for all quotations from Kristapurana in this article. Kristapurana has been transliterated into Devanagari script as well. S.D. Bandelu’s 1956 edition, Phadara Stiphanskrta Khristapurāṇa: Paile va Dusare and Caridade Drago’s Christapuran (1996) are the two Devanagari transliterations available today.

The built spaces—the libraries, museums and institutions—in which Kristapurana manuscripts are housed are as significant as the manuscripts themselves. They are critical spaces that underline Stephens’s position in the annals of South Asian literature and have stood testimony to centuries of colonial violence and cultural transactions.

Three full translations of Kristapurana exist today—one each into English, modern Marathi and Konkani. The English and Marathi translations are by Falcao, a Salesian priest and notable scholar, who has been doing significant work in studying and popularising the text for several years. Suresh Amonkar’s Konkani translation was published in the year 2017. Amonkar has transliterated the text afresh into Devanagari from the Roman script for this work. This translation is significant as it is accompanied by a 300-page preface (published as a separate volume entitled Goenche Saunsarikikaran) with contributions by Amonkar and other scholars. Kristapurana has held pride of place in Konkani memory and literary history for centuries. Amonkar’s translation performs the important task of bringing this text into the Konkani language for the very first time.

The performative aspect of the text has been lost in this journey spanning four centuries. There are no known churches where these verses are sung today. However, one Catholic priest in Goa has put select verses of this text to Indian classical music. Father Glen D’Silva, a trained Indian classical musician, has rendered 25 of the verses of Kristapurana in the khayal style.[29] This is the closest we can get in the present age to understanding how the verses might have sounded when they were sung by locals in Stephens’s times.

Thus the text lives on, in the cultural memory of the region, in Marathi-Konkani literary histories, and in its ‘afterlives’ in the form of modern translations and performances.

Notes

[1] Malshe, Father Stiphanschya Khristapuranacha Bhasik aani Vangmayina Abhyasa, 480.

[2] This system of numbering shows the chapter of Kristapurana from which the quote is taken. For instance, the notation ‘1.2.40’ shows that the extract is from the first Puranna, Avaswaru 2, and verse number 40. The Romanisation used in this article is as per Saldanha’s 1907 edition of Kristapurana.

[3] Malshe, Father Stiphanschya Khristapuranacha Bhasik aani Vangmayina Abhyasa. 425.

[4] Priolkar, ‘Christian Literature,’ 41.

[5] Das, A History of Indian Literature, 191–93.

[6] Wicki, Documenta Indica. Vol.XI., 571.

[7] Saldanha, The Christian Puranna of Father Thomas Stephens, XXIX.

[8] Bassein is now known as ‘Vasai’ in Mumbai, Maharashtra.

[9] Wicki, Documenta Indica. Vol.XII., 437.

[10] The library of the Rachol seminary in Goa is one of the libraries that Swami Vivekananda visited to study Christianity before his speech at the Parliament of Religions, Chicago, in 1893.

[11] Priolkar, The Printing Press, 8.

[12] Ibid., 2.

[13] The Patriarch designate of Ethiopia, who accompanied the printing press, had to halt at Goa, as was the custom for ships in the sixteenth century. The Patriarch decided to extend his stay in Goa for a while and died there in the year 1562, before he could ever set foot in Ethiopia (see Priolkar, The Printing Press, 2–6). The party that accompanied the printing press included Joao de Bustamante, a Spaniard. Priolkar argues that Bustamante must be ‘considered as the pioneer of the art of printing in India’ (see Priolkar, The Printing Press, 8).

[14] Saldanha, The Christian Puranna of Father Thomas Stephens, XXXVII.

[15] Priolkar, The Printing Press, 17, 18.

[16] Saldanha, The Christian Puranna of Father Thomas Stephens, XLIII.

[17] Ibid., XLIII.

[18] Ibid., XLIII.

[19] Ibid., XCIII.

[20] Ibid., LXIV.

[21] The Bhakti movement, the first phase of which began in Tamil Nadu in South India at the end of the first millennium AD, spread to other parts of India over the medieval period in various phases. It was characterised by intense personal devotion and fellowship with God. This religious movement based on loving devotion gave birth to Bhakti literature. According to Sisir Kumar Das, this literature is the ‘supreme literary achievement of medieval India’ (see Das, A History of Indian Literature 500-1399, 26).

[22] This extract, along with the translation, was earlier published in the following research article: George and Rath, ‘“Musk Among Perfumes”: Creative Christianity in Thomas Stephens’s Kristapurana’, 304–324. The portions containing research on the background of Kristapurana was conducted for a doctoral project titled ‘Texts and Traditions in Seventeenth Century Goa: Reading Cultural Translation, Sacredness, and Transformation in the Kristapurāṇa of Thomas Stephens S.J.’ under the supervision of Prof. Arnapurna Rath at the Indian Institute of Technology, Gandhinagar.

[23] Abbot, ‘The Discovery of the Original Devanāgari Text’, 44.

[24] Ibid., 680.

[25] Saldanha, The Christian Puranna of Father Thomas Stephens, XCIII.

[26] Bandelu, Phadara Stiphanskrta Khristapurana, 11; and Malshe, Father Stiphanschya Khristapuranacha Bhasik aani Vangmayina Abhyasa, 25.

[27] Drago, Christapuran, 755–826.

[28] ‘Invisibility and fragmentation’ is a phrase used by Angela Barreto Xavier and Ines Zupanov, in their volume Catholic Orientalism: Portuguese Empire, Indian Knowledge (2015), to describe their experience of doing archival research on Catholic Orientalist works. By this phrase they mean to highlight the gaps in knowledge and ‘glaring historical absences’ in the study of Catholic orientalism (see Xavier and Zupanov, Catholic Orientalism, 288).

[29] Chandawarkar, ‘The Catholic priest who sings Indian classical music!’

Bibliography

Abbott, Justin E. ‘The Discovery of the Original Devanāgari Text of the Christian Purāna of Thomas Stevens’. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 2, no. 4 (1923): 679–83.

Amonkar, Suresh. Goenche Saunsarikikaran. Goa: Directorate of Art and Culture, 2017.

———. Christa Purana (Konkani Translation). Goa: Directorate of Art and Culture, 2017.

Bandelu, Shantaram P. Phadara Stiphanskrta Khristapurana: Paile va Dusare. Poona: Prasad Prakashan, 1956.

Chakravarti, Ananya. ‘Creating a digital archive of Indian Christian manuscripts (EAP636).’ Endangered Archives Programme. 2013. Accessed August 19, 2019. https://eap.bl.uk/project/EAP636.

Chandawarkar, Rahul. ‘The Catholic priest who sings Indian classical music!.’ Herald Goa. January 26, 2016. Accessed August 19, 2019. https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:IRE0dBc9qq0J:https://www.heraldgoa.in/Review/Goa-Social/The-Catholic-priest-who-sings-Indian-classical-music/103395.html+&cd=4&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=in.

Das, Sisir Kumar. A History of Indian Literature, 500–1399: From Courtly to the Popular. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 2005.

Drago, Caridade. Christapuran. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan, 1996.

Falcao, Nelson M., trans. Father Thomas Stephenskrut Khristapuran. Bengaluru: Kristu Jyoti Publications, 2009.

———. Father Thomas Stephens’ Kristapurāṇa. Bengaluru: Kristu Jyoti Publications, 2012.

George, Annie Rachel and Arnapurna Rath. ‘“Musk Among Perfumes”: Creative Christianity in Thomas Stephens’s Kristapurana’. Church History and Religious Culture 96, no. 3 (2016): 304–24.

———.‘Translation, Transformation and Genre in the Kristapurana.’ Asia Pacific Translation and Intercultural Studies 3, no. 3 (2016): 280–93.

Malshe, S.G. ‘Father Stiphanschya Khristapuranacha Bhasik aani Vangmayina Abhyasa.’ Doctoral thesis, University of Bombay, 1961.

Priolkar, Anant Kakba. The Printing Press in India. Bombay: Marathi Samshodhana Mandala, 1958.

———. ‘Christian Literature of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries.’ Literature and Languages. Maharashtra: Maharashtra State Gazetteers, Directorate of Government Printing, Stationery and Publications, 1971.

Royson, Annie Rachel. ‘Texts and Traditions in Seventeenth Century Goa: Reading Cultural Translation, Sacredness, and Transformation in the Kristapurāṇa of Thomas Stephens S.J.’ Doctoral thesis, Indian Institute of Technology, Gandhinagar, 2018.

Saldanha, Joseph L. The Christian Puranna of Father Thomas Stephens of the Society of Jesus. Bolar, Mangalore: Simon Alvarez, 1907.

———. Documenta Indica. Vol. XI. Rome: Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu, 1970.

———. Documenta Indica. Vol. XII. Rome: Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu, 1970.

———. Documenta Indica. Vol. XIV. Rome: Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu, 1972.