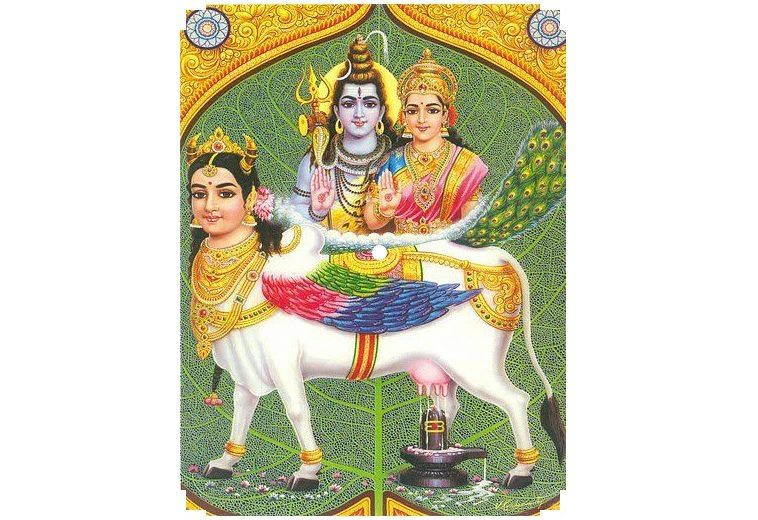

Kamadhenu, the mythical cow-like being that grants wishes, has a popular and enduring presence in various art forms due to its alluring appeal in the cultural imagination. (Photo source: Wikimedia Commons)

Any Indian reader would be surprised and disappointed not to find Kamadhenu, the mythical being that grants wishes, in the Book of Imaginary Beings compiled by the famous Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges. Had he known about Kamadhenu, the erudite librarian-writer who invoked the East in many magical ways would have found in its mysterious amalgamation yet another symbol of infinity that endlessly teases human imagination. The fantastic being Kamadhenu is depicted as a white cow with a female (human) head and breasts, bird’s wings and the tail of a peafowl.

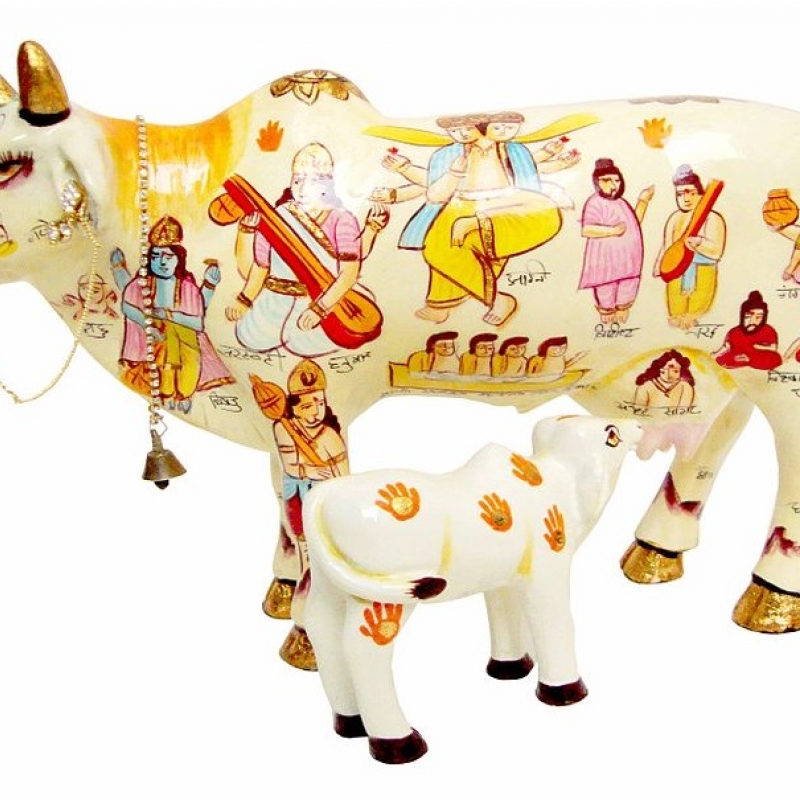

Alternatively, Kamadhenu is also depicted as a white cow with all the Hindu deities inscribed and enshrined in the various parts of her body. As mythology would have it, Kamadhenu emerged during ‘Samudra Manthan’ when the Devas and the Asuras churned the cosmic milky ocean to get the nectar.

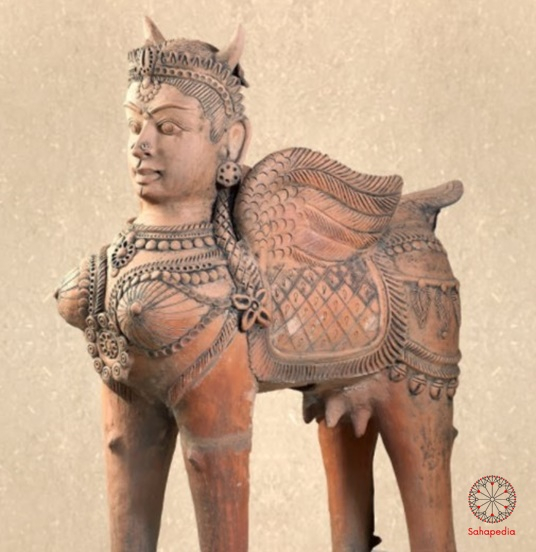

Kamadhenu’s popular and enduring presence in various art forms vouch for its alluring appeal in the cultural imagination. In Tamil Nadu, you would find Kamadhenu representations almost everywhere; most prominently the terracotta Kamadhenus in the roadside shops of East Coast Road (which connects Chennai and Puducherry) and brass Kamadhenus in the shops around temples. The terracotta Kamadhenus (Fig. 1) were originally meant for votive offerings to the village deities but now they are bought both as puja room articles and decorative pieces for home. The terracotta Kamadhenus have fierce eyes, and they flaunt both human breasts and cow’s udders. In most of the brass Kamadhenus, however, the human breasts are subdued or hidden flat to emphasize that Kamadhenu is a cow with a human face (Fig. 2). Terracotta versions, on the other hand, highlight the hybrid form.

Fig. 1: Terracotta Kamadhenu votive offering (Photo source: M.D. Muthukumaraswamy/Sahapedia)

Fig. 2: Brass Kamadhenu from the bazaar shops (Photo source: M.D. Muthukumaraswamy/Sahapedia)

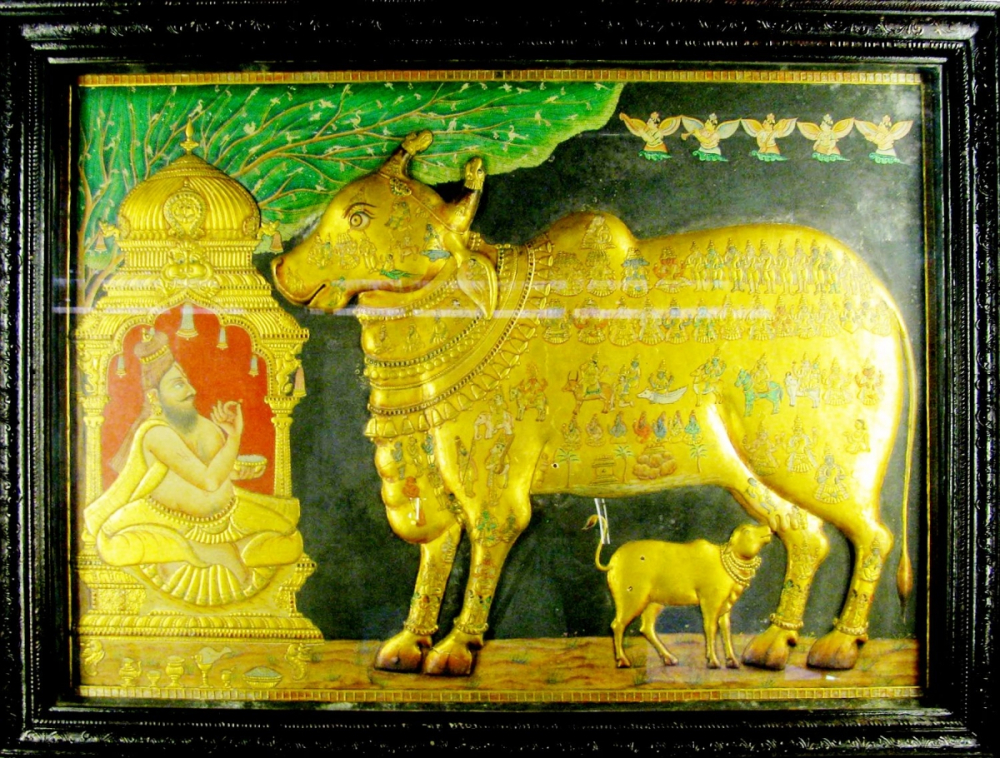

If the terracotta and wooden vehicle versions of Kamadhenu share similarities of form, the brass versions and the Thanjavur painting depictions (Fig. 5) share a similarity of perspectives. Subtle differences emerge from the various interpretations given to the mythological narratives surrounding Kamadhenu. Vettam Mani’s Puranic Encylopaedia records two other names for Kamadhenu (Surabhi and Nandini) and 15 narrative sources, where Kamadhenu appears as an important character. Of all these narratives, the one depicting Kamadhenu emerging from the milky ocean and it becoming a cow in the residence of sage Vasishta gained currency over a period of time. It appears that while the terracotta and the wooden temple vahana versions of Kamadhenu retain or impose fierce motherhood on the iconography of its depiction, the brass and the Thanjavur painting versions align to the sage Vasishta narrative and uphold the Brahminical values of the figurine. This is because the Vedic sage Vasishta is considered to be a Brahmin guru. In a way, the imposition of Brahminical values on Kamadhenu takes away its hybrid form and creates a holy cow with a calf underscoring its motherliness. Referring to the intermingling of forms and narratives, Indologist Madeleine Biardeau wrote that Kamadhenu became the generic name of the sacred cow, which is regarded as the source of all prosperity in Hinduism.

Fig. 5: Kamadhenu as Sage Vasishta's cow in a Thanjavur painting (Photo source: M.D. Muthukumaraswamy/Sahapedia)

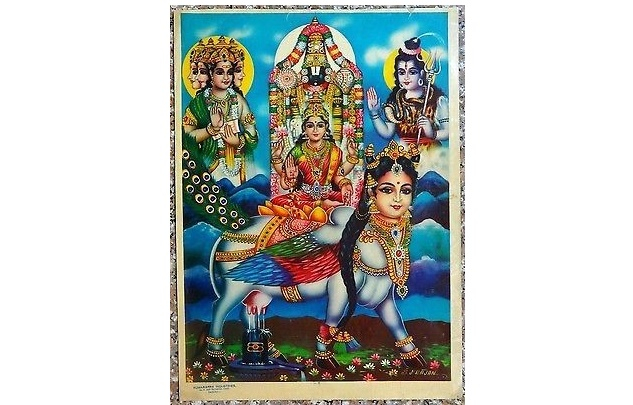

The popular calendar art, however, reduced the motherliness attributed to the Kamadhenu (Fig. 3) and elevated the double bind of enhanced divinity and glamour for its figure. By superimposing the figures of the goddess of wealth Lakshmi on the cow figure, the calendar depiction conveys the wealth-giving power of Kamadhenu. Further, this depiction—in its compromising nod to the brass versions—flattens the female breasts but hangs them between the legs. Sometimes, the calendar art version would feature the face of a film actress, thereby fusing the object of desire and the boon of wish fulfilment in the same figure. The cow’s udders raining milk on the Shivalinga draws its picture from yet another mythological narrative.

Fig. 3: Kamadhenu in popular calendar art.

Fig. 4: Kamadhenu in popular calendar art (Photo source: Pinterest)

Kamadhenu in contemporary art

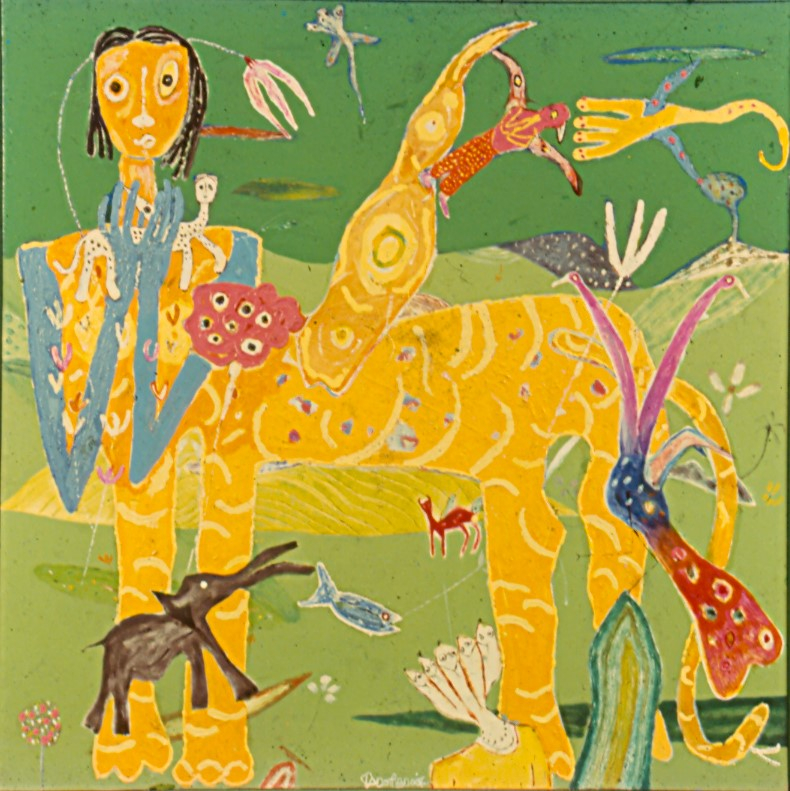

In contemporary art, K Muralidharan’s series on Kamadhenu brings a whole new perspective to its mythology and depiction. In an externalized world of desire and its objects, Muralidharan uses the figure of Kamadhenu to explore the nature of desire itself. Muralidharan’s Kamadhenu assumes a startled look and holds its hands on the cheek while objects and animal figurines are flying around in fantasy (Fig. 6). As a new mythmaker, Muralidharan scarcely pays attention to the old narratives and presents his impressionistic views on the figurine in the modern times. The startled Kamadhenu in Muralidharan’s depiction does not seem to be granting any wish, but in its fully clothed glory and worry, it seems to be shocked by the nature of wish-fulfilment prayers coming in its way (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Kamadhenu by K. Muralidharan (1993); Acrylic on canvas (Photo courtesy: M.D. Muthukumaraswamy/Sahapedia)

Fig. 7: Black Kamadhenu by K. Muralidharan (1994); Acrylic on canvas (Photo courtesy: M.D. Muthukumaraswamy/Sahapedia)

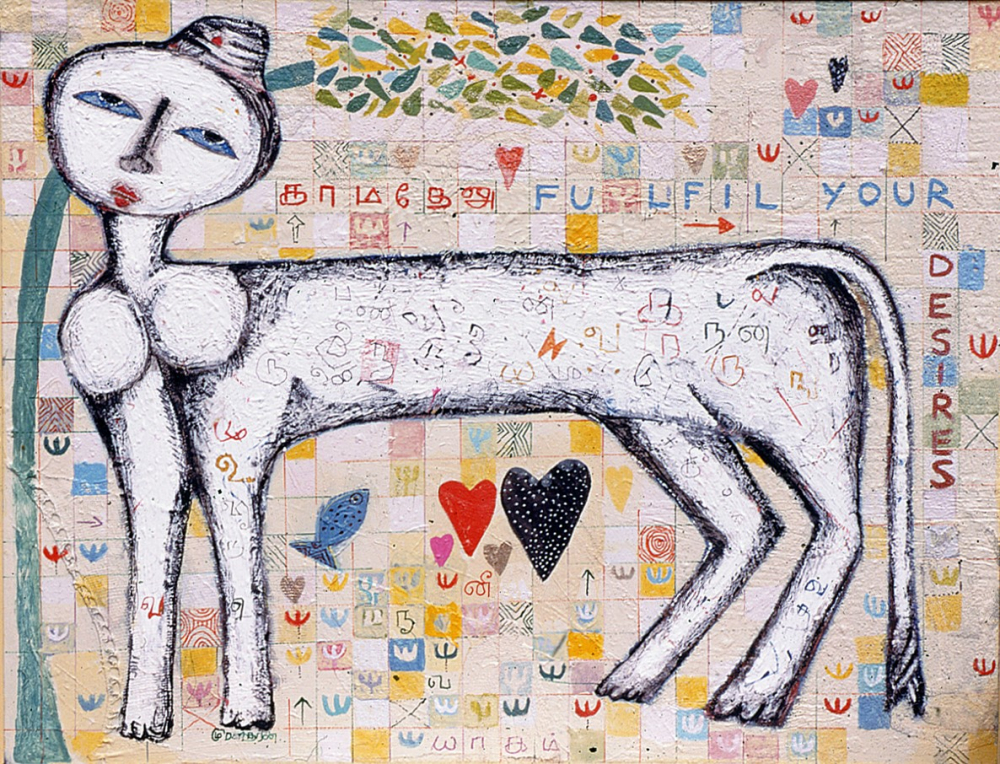

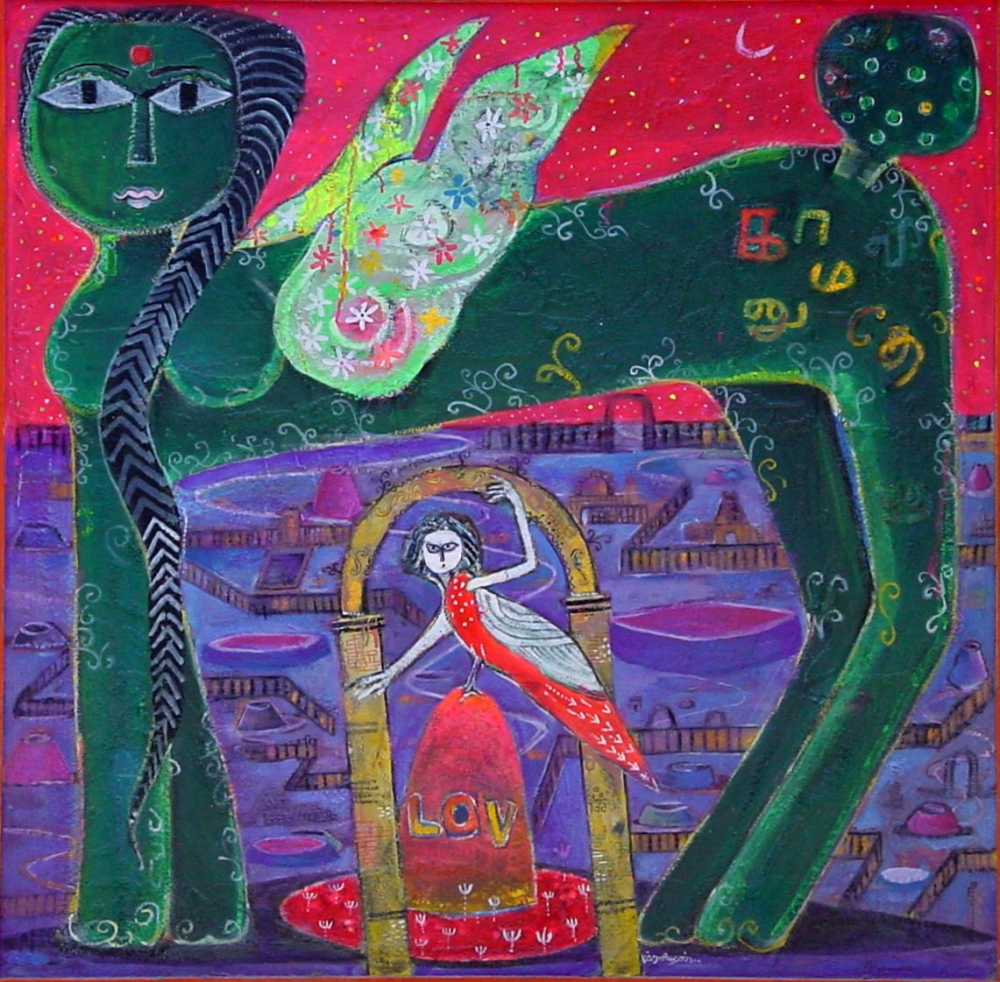

Muralidharan’s black Kamadhenu (Fig. 7) adds colours and gloom to the nature of human desires. It is a skeletal figure, devoid of life-giving expressions (like milk flowing out of the udders), stranded in a desert-like landscape. In contrast, his white Kamadhenu exhibits small breasts, dreamy eyes, long hair and pouted lips (Fig. 8). As if the message of his white Kamadhenu would be lost on its viewers, Muralidharan writes ‘Fulfil your desires’ in letters in the painting and conveys that he equates love with desire. His perspective becomes all the more pronounced in the green Kamadhenu (Fig. 9), where the mythical figure looms large over a temple city. Again, Muralidharan makes alphabets a part of his painting to convey that ‘love’ should be the fountainhead of desires for wish fulfilment.

Fig. 8: White Kamadhenu by K. Muralidharan (2001); Acrylic on canvas (Photo courtesy: M.D. Muthukumaraswamy/Sahapedia)

Fig. 9: Green Kamadhenu by K. Muralidharan (2010); Acrylic on canvas (Photo courtesy: M.D. Muthukumaraswamy/Sahapedia)

Fig. 10: Terracotta sculpture of Kamadhenu by K. Shyamkumar (Photo courtesy: M.D. Muthukumaraswamy/Sahapedia)

In contrast to Muralidharan’s externalized multiple Kamadhenus, contemporary artist K. Shyamkumar’s terracotta sculpture (Fig. 10) internalizes Kamadhenu’s wish-granting prowess onto sculpture itself. With its exaggerated breasts, slanted head, and bent horns, Shyamkumar’s Kamadhenu seems to be frozen and submerged in the pleasures of giving. Suddenly, through his sculpture, the primordial figure of Kamadhenu and its universal symbolism and imaginary become accessible. Shyamkumar’s sculpture indirectly conveys that the universe is connected and fused across the species in the act of giving and granting each other’s wishes and boons. Standing unique among the multitude of Kamadhenus, Shyamkumar’s sculpture asserts the poetry of unconditional giving.

Borges would have delighted to see such a variety of wondrous depictions of Kamadhenu available for Indians to practise piety in relation to desire and wishes. He would have even written a sentence very similar to Yogavasishta’s famous saying, ‘The world is like an impression left by the telling of a story.’

Views expressed are personal.