A well-used wooden block with a printed textile, Machilipatnam

The term kalamkari literally means ‘work done with a pen.’ The term is now inseparably attached to the painted and block-printed cotton and silk textiles, produced in the Coromandel Coast (parts of Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu) of India. Today, two of the most prominent centres of kalamkari production are Srikalahasti (Chittoor District) and Machilipatnam (Krishna District) in Andhra Pradesh. While in Srikalahasti, the textiles are literally painted with pens made out of bamboo and cotton, in Machilipatnam, the line drawing done with a pen is transferred onto wooden blocks which are carved and then used to print fabric. In Machilipatnam, the production is carried out in karkhanas (commercial workshops), where the block makers, washers and printers work under the same roof. In Srikalahasti, the textiles are produced by small family units where the members work together. This essay discusses the history, stylistic development, materials and techniques of kalamkari at both Srikalahasti and Machalipatnam.

History and Development

Fragments of Indian block-printed cloth dating to the late Roman period have been discovered from archaeological sites in Egypt. However, the oldest samples from the Coromandel Coast itself are from 13th- 14th century A.D.

Srikalahasti is one of the most important pilgrimage sites for Hindus because of presence of the Srikalahastisvara temple, which is dedicated to Lord Shiva. Historically, textiles from Srikalahasti were essentially used as canopies and hangings that acted as backdrops to the images of the deities at the temple. The themes of these paintings are derived from Hindu religion and also from nature— bird and tree of life motifs abound. The temple at Srikalahasti gained prominence under the Pallava kings (6th- 9th century AD), and was further developed during the Chola (9th- 13th century AD) and Vijayanagara (14th- 17th century AD) Empires.

The textiles produced in Machilipatnam were meant for clothes, prayer mats, bedspreads, tapestries and hangings. The printing techniques used to produce these textiles helped in mass production. The motifs from Machilipatnam are often cross-cultural and combine local motifs with those derived from Persia and Europe. Machilipatnam, was a busy port during the late medieval period. The port was especially bustling from the 15th-17th century A.D. As the textiles produced in Machilipatnam were free from any kinds of cultural or religious restraints, they displayed varied imagery starting from stylized plants, creepers, geometric designs to animals and human figures. These representations are important sources for the study of the contemporary social scenario.

Materials and Techniques

The materials and techniques for making the two types of kalamkaris are similar. In Srikalahasti, the cotton cloth is first washed with water thoroughly to remove starch and other oily substances. After drying, the cloth is dipped into buffalo milk mixed with myrobalan fruit dust, and then, after squeezing out the excess solution, it is dried again. Next, the initial drawing is done with charcoal pencil made from burnt twigs of the tamarind tree. For colouring, a pen made of bamboo is used. One side of the bamboo stick is carved to get a sharp tip. Near this tip, a piece of cotton cloth is wrapped and then tied with thread. The solution for drawing the outline is locally called “kasim” and is made by adding 500 grams of sugarcane jaggery, 100 grams of palm jaggery and 1 kilogram of rusted iron into 10 litres of water. The solution is kept for around twenty one days before it is used. The bamboo pen is dipped into kasim, gently squeezed to release the liquid and then used for drawing. A piece of cotton is kept at hand to blot the excessive ink from the surface. In the area that has to be painted red, initially a solution of alum water is applied with a blunt pen. Generally, the background of these textiles is painted red. To get maroon, instead of red, a small amount of kasim is added to this solution. Separately, alizarin solution is prepared using 50 grams of alizarin diluted into water (for around 6 metres of cloth) and then added to around 15 litres of boiling water. The cloth, drawn with kasim and alum solution is dipped into the hot water and kept for around 45 minutes. The textiles are then washed in the river Swarnamukhi which is nearby. The river is shallow which makes it suitable for washing. After the process, the cloth is dried and again dipped into buffalo milk. For yellow, the dust of ripe myrobalan fruit, mixed with alum solution is used. For orange, chvalkodi and alizarin is mixed with the myrobalan-alum mixture. For blue, indigo is used. After this, the cloth is washed again in water before it is finally ready for use.

In Machilipatnam, the washing of the cotton fabrics is done at the Kalia Canal. Then a process similar to the one described above is used. In Machilipatnam, for the block printed textiles, line drawings are not necessary. The textiles produced here can be monochromatic or polychromatic and for each colour, separate blocks are used. The manufacture of these textiles is a collaborative process. The whole unit is divided into several sub-units. The first sub-unit is the block maker’s workshop where the artisans are mostly from the carpenter’s community. For making the blocks, a cross section of teakwood is generally used. Blocks are carved using the relief process, where the positive area, which has the design that will be transferred onto the cloth, rises above the sunken negative area. In the printing sub-unit, the colouring process usually starts with the outlines and moves towards filling-in of the inner portions of the design. For polychromatic printing, the black and red portions of the design are printed first and then the cloth is washed and boiled. Unlike the process at Srikalahasti, alum solution is not used here for the red colour. All the colours are stored in flat rectangular wooden vessels and covered with several layers of cotton cloth or jute. After printing, the fabrics are dried and taken to the washing sub-unit. This unit is usually open from all four sides and consists of one or more open ovens. These ovens are, till today, fuelled with rice husk and wood powder. Big semi-circular vessels made of iron are placed over these ovens for boiling the fabrics. While boiling, leaves from the local forest, known as gaja, are added to the water to fix the colours. After boiling, they are dried and sent for further printing with yellow and blue colours. After this, the fabrics are washed again in boiling water. Finally the finishing touches are given, which sometimes includes embellishment by hand.

Blocks from a block-makers’ workshop

Washing sub-unit, Machilipatnam (Image courtesy Shatarupa Bhattacharyya)

After the fabrics have been washed, they are left to dry under the sun

Printer’s workshop, Machilipatnam

Importance of the region

The geography and social structure of an area play an important role in the nature of its art forms. The availability of materials, existence of skilful artisans and a consistent clientele are all important factors. The fact that there was ample production of cotton fabric in southern India, ensured the supply of the raw materials to both Srikalahasti and Machilipatnam. Andhra Pradesh, along with neighbouring Karnataka and Tamil Nadu are well known for the production of quality cotton even today. The other materials needed- natural colours and different kinds of wood (for the blocks and pens) were all available easily. One mandatory requirement is running water, as the process involves plenty of it. River Swarnamukhi, in Srikalahasti takes care of this requirement, whereas in Machilipatnam, the canal emptying into the Bay of Bengal acts as the source of water.

Though geographically Machilipatnam and Srikalahasti are not too far away from one another, the proximity to the sea has worked more in favour of the former, as Machilipatnam was a distinguished port even in medieval India. The preserved samples of Kalamkari from museums from different parts of the world seem to indicate this too. For the English, Dutch and French traders, the port was well-known for the textile trade. Being a town of importance, both for the Vijayanagara rulers and Bahmani kingdom (later the Qutb Shahi kings); Machilipatnam was a ‘melting pot’ of cultures. In Srikalahasti, textiles were mainly produced for ritualistic purposes and their use remained confined within the temple space. Vijayanagara rulers like Krishnadevaraya, patronised the Srikalahastisvara Shiva temple, a fact which is mentioned in the inscriptions from that time period. This points to the fact that this region was already a distinguished site of pilgrimage before the 16th century. Comparing not only the purpose of making the textiles, but also the cultural atmosphere surrounding the workshops of the artists it is evident that the textile works are greatly influenced by the local geography.

Multi-disciplinary linkages seen in the Veerabhadraswamy temple murals

Often the inspiration for various art forms is deeply rooted in the surroundings. There are stylistic similarities between the textiles traditions of Srikalahasti and the temple murals from the Vijayanagara period. The murals at Srikalahasti are very detailed and have been made with bold black lines. This kind of style is also seen in the rendering of the murals at the Veerabhadraswamy temple built in 16th century A.D at Lepakshi, Veerabhadraswamy, a Tamasik form of Lord Shiva, is the residing deity at this temple. The temple was built during the rule of Achuyta Deva Raya (1529–1542). Contrary to this, local legends attribute the building of this temple to the court treasurer Veerupanna, who was then blinded as punishment, giving the temple the name ‘lepa-akshi.’ It is also conjectured that the temple derives its name from the literal meaning of the word ‘lepakshi’ which is ‘embalmed or painted eye.’ A numbers of other legends claim that the temple was founded during the age of Ramayana, allotting it an even greater antiquity. It is said that the Mythical bird Jatayu died here, and the lamentations of Rama, which sounded like “Le/hey Pakshi!” became the source of the name. At the temple itself, a black stone exists inside the garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum), which was worshiped as Veerabhadra, before the existing temple was built around it. This monolithic stone is referred to as “kurmashila” because of its visual similarity to the shell of a tortoise.

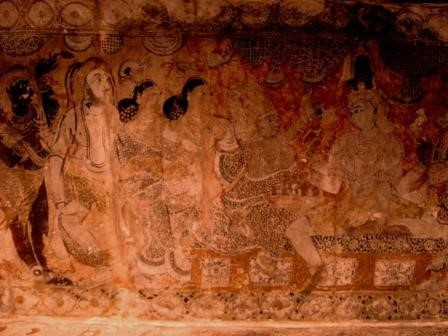

The ceiling of rangamandapa (pillard hall), antarala (antechamber), and pradakshina path (circular pathway) around the garbhagriha of the temple is filled with murals. Except for the images of a few deities, most of the figures are executed in profile. The direction of their gaze and gestures lead the viewer eyes as the narrative unfolds. Although the murals were not painted all at the same time, they follow an overall style.

In terms of colour schemes, first the base for the paintings is prepared with lime, and then red, ochre and black colours are used for the line drawing. On the ceiling of the corridor, adjacent to the back wall of the garbhagriha, a few unfinished line drawings have survived. The colour, which is thickly pigmented tempera, was applied after the drawings had been made. White is used in some of the figures to define drapery and for the details of the ornaments. In the style of drawing, the figures are not rendered to express three dimensionality of the figures and instead, the flowing lines of black are used to define the contours. The lines are free-flowing and rhythmic. For the figures, the iconographical details mentioned in the corresponding texts are followed. For example the image of Ardhanariswara, which is the union of Shiva and Parvati, follows all the iconographic specifications— Shiva wears the jatamukuta, a towering headgear composed of the curls of his matted hair, whereas Parvati wears the kiritamukuta, which is again a towering, conical headgear, made of metal and precious gems. In four hands, Shiva holds axes while another hand is in abhayamudra (gesture of fearlessness). Parvati holds a lotus in one hand, while the other hand is in varadamudra (gesture of generosity). The belly is slightly protruding, which is also seen in the other paintings and sculptures of the contemporary period. There is space for narration in the form of patterned bands above and below the scene. In the case of the Lepakshi murals, the border designs are an important part of the whole composition. It can be assumed that by the 16th century, the bordering was conventionalised, and the evidence for this can also be found in other forms of painting on textiles and scrolls as well.

The borders of the murals and textiles of Srikalahasti have stylistic similarities. Anna L. Dallapiccola describes the composition of the borders found at Srikalahasti— “The external border displays a lotus, or a ‘cartwheel’ design, followed by a thin band pilli adugu, ‘cat’s footsteps’ (Dallapiccola 2010:250). The designs of the richly executed drapery of the figures have stylistic similarities with the textiles of Machilipatnam. Furthermore, the designs of creepers and diamond shaped lattices with floral motifs (Rao 2004:140) can only be achieved with block prints. Woven textiles, which are comparatively more expensive than block-printed ones, are also identifiable in some cases, especially in the costumes of the royalty depicted in the paintings.

Interpretation of the narrative

The narrative describing the surface of the murals in the temple, the painted temple cloths and textile fabrics will be briefly discussed in this section, aiming towards understanding how such a visual narration can help us make connections between these practices.

Panels depicting Shiva, Devi, Tumburu and other devotees and mendicants from ceiling of Rangamandapa of Veerabhadraswamy temple, Lepakshi, 16th century A.D.

The panels (images above) depict Shiva being greeted by Devi while they are both seated on a pedestal (asana). Devotees and mendicants are standing on either side of these figures. Each figure is intricately executed with distinguishable characteristic features. In the left corner, the two mendicants are differentiated through their body colour, hairstyles and costumes. Both of them are wearing animal skins, and the motifs suggest that one costume may be of tiger skin while the other of jaguar skin. The costumes of the devotees may help reveal different kinds of clothing styles during the Vijayanagara period. In the scene, the minute details in the design of the dress, pedestal and curtain are very similar to the printed and painted textiles of the region. These costumes are painted by applying flat washes of colour. This technique of colouring is also found in the textile and scroll painting traditions of Telengana (Cheriyal Pata). The figures are placed one besides the other with some overlapping. In the Srikalahasti textiles, the arrangement of figures in rows, the division of the entire pictorial space into horizontal bands and use of patterns appear very similar to that of the murals discussed above.

Detail from “Tree of Life”, Kalamkari, Srikalahasti

Samples of block printed cloth from Machilipatnam

Conclusion:

The study of the history and evolution of kalamkari at both Srikalahasti and Machilipatnam reveals an amalgamation of a diverse set of influences. The two regions developed their designs not only in response to the visual traditions of the region but also to the needs of the market. A review of the two kalamkari traditions also reveals the similarities in their techniques. Today, many kalamkari artists continue to produce items of furnishings and fabrics for the modern market. While these industries cater to new markets with ever-changing innovations, at both Srikalahasti and Machalipatnam the traditional modes of production have survived and are gaining wider appreciation due to their vibrant designs, use of natural colours and as symbols of the region’s heritage.

Acknowledgements:

Prof. Sharada Srinivasan, P.V.R.K. Prasad, Naga Sai Kumar, K. Gangadhar, K. Narsaiah, Trinadh Rakesh and K. Venkatesh.

References:

Dallapiccola, Anna L. 2010. South Indian Painting: A Catalogue of the British Museum Collection. India: Mapin Publishing House in association with The British Museum Press.

Verghese, Anila and Anna L. Dallapiccolla, eds. 2011. South India under Vijayanagara. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Rossi, Barbara. 1998. From the Ocean of Painting. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sivaramamurti, C. 1993. The Art of India. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Inscriptions of the Vijayanagara Rulers Vol. V [Tamil Inscriptions] (edited by Professor Y. Subbarayalu and Dr. Rajavelu).

Ritti, Srinivas and BR Gopal, eds. 2009. Inscriptions of the Vijayanagara Rulers: Volume III. New Delhi: Indian Council of Historical Research.

Rao, D. Hanumantha. 2006. Lepakshi Temple. Delhi: Bharatiya Kala Prakashan.

Rao, T. A. Gopinatha. 1914. Elements of Hindu Iconography: Volume 1-4. Madras: The Law Printing House.