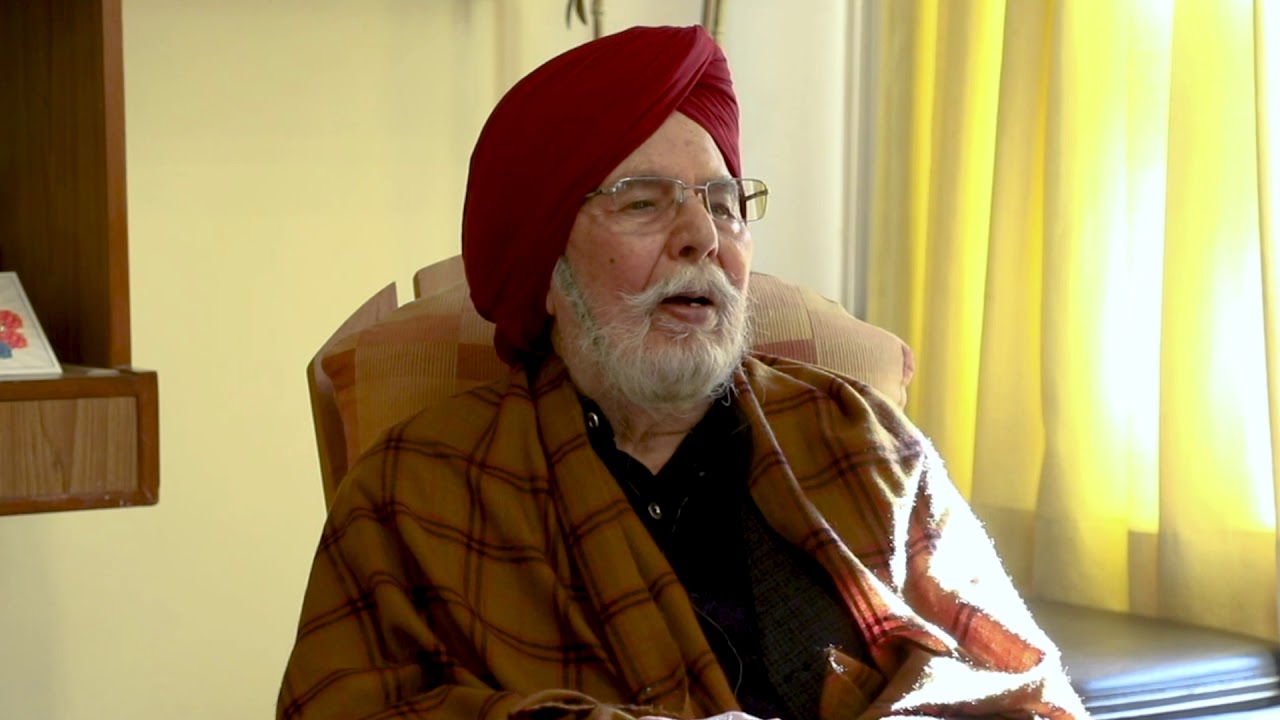

Jagtar Singh Grewal is a prominent historian of medieval and modern Indian history, especially the history of the Punjab and Sikhs. He has published over three scores of books—monographs, collections of articles, Persian sources and other edited works—and over a hundred research papers in the past 55 years. His publications relate to the history of historical writing, Indian history, both medieval and modern, history of the Punjab region from pre-historic times to the present, Punjabi literature as a source of history, and the history of the Sikhs from the late fifteenth century to the present.

Born in a Sikh village in Punjab, in pre-Independence India, Grewal was interested in history since childhood. He received his PhD in History from the University of London in 1963 for his thesis on British historical writing on medieval India. This was the first thesis on historiography by an Indian scholar. Later it was revised and published as Muslim Rule in India: The Assessments of British Historians (1970).

Grewal joined the faculty of Punjab University in 1964 and, in 1969, his Guru Nanak in History, was published by the university as a part of Guru Nanak’s quincentenary birth celebrations. Path-breaking in its approach, the book drew from sources other than Guru’s compositions, analysed the political, social, and religious milieu of the times and his responses to them. This work earned Prof. Grewal his D.Lit. in 1971. He was invited by Cambridge University Press in 1980 to write a volume on the Sikhs for the New Cambridge History of India series. A round study of change and continuities in the context of the region and the country, The Sikhs of the Punjab, was published in 1990 and has been reprinted many a time to become a classic.

The importance of urban studies was recognised in India when Prof. Grewal published In the By-Lanes of History: Some Persian Documents in 1975. In this work, Grewal studies 150 deeds of sale, mortgage, gift, agreement and declaration executed in the court of the qazi of Batala town from the late seventeenth to the early nineteenth century in Punjab. Through a rigorous analysis of these documents and their seals and hundreds of attestations in different scripts, combined with the evidence of other sources, including frescos, inscriptions, graffiti, and field work, Prof. Grewal reconstructs the history of a medieval Indian town.

By the time he retired in 1987, Prof. Grewal had gained a formidable reputation as a historian, known for his rigour and meticulousness. In 1984 he had been elected as the General President of the Indian History Congress. The Indian Council of Historical Research invited him to be a National Fellow, and he wrote two books: Historical Perspectives on Sikh Identity (1997) and Contesting Interpretations of the Sikh Tradition (1998) to facilitate a dialogue between Western academia and Sikh scholars. Subsequently, he was invited by the Centre for the Study of Civilizations, New Delhi, to be an Editorial Fellow for preparing two volumes on the History of Medieval India: The State and Society in Medieval India (2005) and Religious Movements and Institutions of Medieval India (2006). During 2006–08, he was invited as a Visiting Professor at the Punjabi University, Patiala, and he delivered over a hundred lectures on different themes. Selections from these lectures have been published by the university in two volumes. Invited to be the Professor of Eminence at the same university during 2010–16, he produced a monumental study, entitled Master Tara Singh in Indian History: Colonialism, Nationalism, and Politics of Sikh Identity (2017). This monumental work reveals nearly all important aspects of Master Tara Singh as the most important Sikh leader in twentieth-century India.

Some of the other publications of this phase are significant for the choice and treatment of the subject by Prof. Grewal. In the History, Literature, and Identity: Four Centuries of Sikh Tradition (2011) he analysed the core of Sikh texts from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century to discuss issues like conscious conceptualisation of a new dispensation, processes of community formation, social transformation, and politicisation leading to the emergence of a new political order. This is complemented by another volume analysing secular Punjabi literature from the thirteenth to the twentieth century, entitled Historical Studies in Punjabi Literature (2011). Prof. Grewal emphasises that the emergence of new literary genres during the colonial period is a pointer to social transformation, but a work of literature has to be unwound to get at the historical situation that produced it. Prof. Grewal’s most recent work, Guru Gobind Singh (1666-1708): Master of the White Hawk (2019) highlights that the unifying theme in the life of Guru Gobind Singh was confrontation with the Mughals, which culminated in a struggle of political power and the creation of the Khalsa in 1699 as a political community with the aspiration to rule.

Several awards were conferred on Prof. Grewal, including those by the Asiatic Society, Kolkata, Asiatic Society, Bihar, Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Public Library, Patna, Sikh Educational Society, Amritsar, Punjabi University, Patiala, and Panjab University, Chandigarh. In 2005, the President of India awarded the Padma Shri to Prof. Grewal for his intellectual and academic contributions.

Following is the final segment of the edited transcript of video interview with Prof. J.S. Grewal conducted jointly by Prof. Indu Banga and Dr Karamjit Malhotra

Karamjit Malhotra (KM): Sir, I was looking at your list of publications and I notice that you have produced over 60 works.

J.S. Grewal (JSG): Really.

KM: Yes. And there are over ten joint works. So the latest work came this year on the political biography of Maharaja Ripudaman Singh. So what has been your experience of preparing joint works or producing joint works?

JSG: The first thing I can think of is that every joint work arose out of a particular situation. If I am thinking of The Jogis of Jakhbar, the study of those documents, and the Vaishnavas of Pindori, another sect, then Dr Goswamy had acquired those documents. And he approached me. And I thought it was a good idea and therefore we decided to work together. And it was a great pleasure working with Dr Goswamy. He had a deep interest in the subject and we could sit together for half an hour or a full hour in order to decipher a single word. It would take that much of time—several possibilities … consult the dictionary and see if it really fits in. So then the work got divided automatically into two parts. Part one, the history of the institution, the Jogis of Jakhbar, the math of the Jogis: how did it come into existence, what is the history. And the second part, what is the significance of these documents, which was my concern, very largely, because the significance was to be seen in the context of Indian history and medieval Indian history, which was supposed to be the area in which I was interested.

KM: So it was complementary.

JSG: Complementary in the sense that the two parts came together. But it was a very happy sort of collaboration. I learnt a lot from Dr Goswamy and also from the close study of these documents. I felt very happy about that. And, as I said earlier, we made a mistake about the Jogis of Jakhbar. We did not publish all the documents. The Sikh part, the orders of the Sikh rulers were not included, which was very unfortunate. Later on, we couldn’t get those documents.

KM: There are two works on translations: one with Prof. Banga and the other with Prof. Irfan Habib.

Indu Banga (IB): Three rather: Civil and Military Affairs also. Three.

JSG: The work which I did with Prof. Banga—that is not like the earlier work that is complementary, one part, other part. We are both interested in the same area and we worked together, discussed things and came to some sort of understanding. So then one of us can write, the other can revise or read it.

KM: And about Guru Gobind Singh, so what kind of collaboration was that?

JSG: That was a work done for the university and it was a department’s work and it was complementary only in the format. We divided the work. One part to be done by one person, these chapters to be done by A, the other chapters by B. So they remained two independent parts.

IB: You worked on the mission of Guru Gobind Singh.

JSG: I wrote the chapters on the institution of the Khalsa and related history.

IB: And the Introduction to that.

JSG: And the Introduction which is the context, the Mughal empire, the Sikh panth, the Sikh movement and the hill states. These three elements in the context.

IB: But in the present work, the most recent work which is in the press now, the context of the Mughal empire runs through the entire work, this is my impression.

JSG: It is both now. In the beginning also there is introductory sort of description of the situation. This is confined to the reign of Aurangzeb, the situation of Guru Gobind Singh. And then the different chapters, what is the context so far as the Mughal empire is concerned, giving that context with the chapter. Five years, ten years, three years, whatever.

IB: This particular work, Historical Writings on the Sikhs: Western Enterprise and Indian Response, which covers the period from 1784 to 2011, it came out in 2012. I regard this in one sense as a continuation and in fact an expansion of your work on British historians of medieval India.

JSG: There is a difference. This is not only about the British but also about the Indian historians, which is not there in the earlier work.

IB: So they have come of age.

JSG: And also, I am suggesting that the Indian historians are writing in response to what has been written by the British. Therefore, they are trying to—from their viewpoint—to correct or to reiterate whatever the position may be, but with reference to, with response to what the British had written. And eventually becoming sort of independent of that. What we can say about the controversy of the ’80s, ’90s is that it is the revolt of the traditional Sikh historians against the West.

IB: I think this is very well put, a revolt.

JSG: It is.

IB: This work, Master Tara Singh in Indian History, its subtitle is Colonialism, Nationalism and the Politics of Sikh Identity. It seems to be in some ways a culmination of your earlier work on Sikh identity, your understanding of colonialism as well, and in many ways, it is a breakthrough in our understanding of Master Tara Singh, who has been a very controversial subject. So what would you like to say about this work? It took you some years to complete it.

JSG: It took me six years to write. And this was made possible by the Punjabi University at Patiala. There were a few scholars, few historians who thought that Master Tara Singh had not been treated well by historians. So they persuaded me to accept this idea that a biography of Master Tara Singh was desirable, was needed. So then the Vice Chancellor, Punjabi University, he sort of offered to sponsor this study, finding some way out, and I was invited to the university as a professor of eminence. The understanding was that I would work on this project which I did. They did not think it would take such a long time, but then my concern, my interest went on increasing and I wanted to satisfy myself that I have written what I could and not left the study half way somewhere.

What I discovered was that it was known that Master Tara Singh remained one of the topmost leaders, or the topmost leader, of the Sikhs for 40 years. Four decades is a long time. And therefore, he needed a kind of work which did justice to what he had been doing and saying. This was the idea. When I started collecting information about his life, I found that several people had written on him in Punjabi and in English (mostly in Punjabi), but more than that, there were other sources of information. Master Tara Singh himself had written a lot in essays and books and novels, and that was in itself a considerable volume. And then I found that Master Tara Singh figures in the correspondence of national leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel, Rajendra Prasad and to some extent Jinnah. Jinnah also.

IB: Mahatma Gandhi?

JSG: Mahatma Gandhi in a way, I was coming to that. If we don’t think of Master Tara Singh alone but of the Akalis and the Sikhs in general, then the field becomes still wider, and Mahatma Gandhi would figure in a more prominent way than anyone else. So Mahatma Gandhi’s view of (the) Sikhs as a people, his view of Sikhism as a religion, all these become important, and they remain an important factor in the situation when he is talking about or dealing with the Sikhs. So this material was there. And then in (the) official records which have been published: I did consult some files in the archives, unpublished files, but then I found that a very large volume of material had been published already, official documents, so that was another area. So there was a lot of information which had to be dealt with.

Now what have I done in the book is the most important question. I think I have tried to place Master Tara Singh in the Indian context of these decades we are talking about. And my primary concern was to make his position clear in relation to the various problems developing from time to time, including the struggle for independence, which would be very important, in which he participated in a big way.

And then the question of the re-organisation of states and there again his old supporters, they had different views and Master Tara Singh was left alone. How he rebuilt himself: rebuilt his leadership, creating a new following and pursuing what he thought was the best thing for the Sikhs to do, and thereby coming into conflict with Jawaharlal Nehru. So they developed a sort of personal hostility in due course. So the interest of the book I think throughout is Master Tara Singh’s response to the given situations, which are changing with time, and Master Tara Singh is changing in the way in which he would like to deal with them, but remaining faithful to some of his basic ideas. And one of the basic ideas, clearly for him, from the very beginning, was that the Sikhs had an identity of their own.

So this was the basis of his politics. But this was not his creation. This was the creation of the Akalis. And the Akalis had sort of adopted it from the Singh Sabha movement. And I talked about the Singh Sabha movement when I referred to Bhai Kahn Singh Nabha and the controversy about Sikh identity. How I look at the question as rather more complicated than simply a late-nineteenth-century debate, because the issue of identity would arise with the founding of the new faith by Guru Nanak, the founding of a new panth. Guru Nanak is not only talking—he is using the word Sikh—but he is talking of their association, he is talking of their activity. So for him, the following, the fraternity has been established. This is in the compositions of Guru Nanak himself. And therefore, the conjectures of historians like Harjot or McLeod, they are not really relevant anymore, because you have the original evidence of the compositions of Guru Nanak.

And also, we have the outline of the basic institutions, for example, the Granth Sahib. The basis of this would be the fact that Guru Nanak’s own compositions were used for congregational worship. And the institution of Dharamsal, the place where there is congregational worship of the Sikhs, that goes back to the time of Guru Nanak and langar was an integral part of that. So this is the most ancient, the first and foremost institution of the Sikhs, the gurudwara, and you can see the importance of this institution throughout history, and struggle about its control and everything connected with the gurdwaras. They are still important. There is a joke now that if you have five Sikhs in the USA, you have six gurdwaras.

One simple point I wish to mention, this is the most important: Guru Nanak chose his successor in his lifetime, installed him on the gaddi in his position. This gave rise to the idea that the position of the disciple and the guru is interchangeable, and also that guruship is a continuous phenomenon. This led ultimately to the idea that guruship is internal, and when the guruship came to an end so far as the persons were concerned, it was vested in the Granth and the panth so that as long as the Granth is there, as long as the panth is there, the Guru is there. So this goes back to the time of Guru Nanak in that sense. So every important institution has its roots in the time of Guru Nanak. That is why he is important. I am simplifying in order to make it clear.

IB: It is. I think it has been made very, very clear.

JSG: The subject is more complex.

IB: So looking at this huge work and your continuing interest in the scholarly pursuit of history, what I find equally remarkable is that you have also written for the common reader. And in fact, your Sikhs of the Punjab was meant initially for the common reader. It is a different matter that because of, I should say paucity of good work, it has come to be regarded as a reference work as well. And for every researcher it is a must to start with. But then you have written for children, written on Maharaja Ranjit Singh, a short book for children, for the young reader, and you have written for school children, school textbooks. And you have also tried to incorporate the study of local monuments at school level. I am reminded of the review of syllabi for the Punjab School Education Board or the Review of History Textbooks for the NCERT. So the concern for the children has been there, and even now at present you are working on history textbooks for Class 11 and 12 for the Punjab School Education Board. So do you think that this concern for the children, concern for the lay reader (common reader), is partly arising out of your idea of commitment to history, or commitment to society, or both?

JSG: It would be both, in a sense, because I think knowledge of history, for anyone to have, is helpful in several ways, not only personally but also socially, as a member of society. Also politically: you become more aware of the situation in which you are living. So the primary function, for me, of history, is to enable you to understand yourself, your position in society and the position of other people in society, so that you get some idea (of) where to go, in which direction to move. I subscribe to the idea that the past, the present, and the future, they are sort of one continuity in spite of the changes, and it is important to know where we have come from, and also if we have some idea of what kind of changes we need or we would like to have, in which direction we would like to move. So in this way the function of history to my mind is very important. It is not merely a profession, merely a job, or something which entertains you, which interests you, but something which is needed by the society, which is essential for the society. This is how I look upon history.

IB: You were at Amritsar in 1984. In fact you were the Vice Chancellor from 1981 to 1984, which were the most difficult years one would say as far as the impact of militancy is concerned. So how did you function during that period and how did you take the stresses of that time?

JSG: I think in the first place I was not aware of all the implications which we know now. It was a serious situation but I didn’t realise to the extent that it really was. This was one part. Secondly, I felt that I was the head of an institution, and I should serve as an example to my colleagues, and therefore when they found me working, even under the stress, they felt encouraged, and when they found that I attended to my duties as regularly as possible, that also made a difference. When they found that I did not encourage any sort of rift among the colleagues, they appreciated that.

IB: That is, between Sikhs and Hindus?

JSG: In terms of Hindus and Sikhs.

IB: Well, I was just looking back at your career and it occurred to me that you have been very closely and productively associated with all the three universities in the region beginning with Chandigarh, then going to Amritsar, and then spending almost twelve productive years in association with the Punjabi University, Patiala.

And it was I think a very good decision on the part of the Punjab University when they recently instituted the Gyan Ratan Award and they decided to give this award to you as the first recipient of Gyan Ratan for Excellence in Research in Social Sciences.

And Punjabi University recently conferred Bhai Kahn Singh Nabha Award on you in addition to several other awards. Sikh History conference…

KM: Sikh History conference, they had also given a Life Fellowship.

IB: Yes, apart from the Life Fellowship that we talked about, and Sikh Education Society conferring its award for Excellence in Sikh History and Research. Khudabaksh Library conferring an award for your study of Sufism, the President of India conferring that award.

So a cross-section from different angles, from the social sciences angle, from the angle of Sikh history and Sikh literature (literature also has been particularly taken note of in this award for you), and the Life Fellowship, and from the point of view of the study of Sufism and Islam.

So apparently you have been as much at home in medieval India as in Punjab and Sikh history over these years. And some people have called you the greatest historian of the Sikhs, and some have characterised your work or you as the greatest historian of the Punjab. These superlatives may be embarrassing for you, but would it be right to say that these fields have not been the same since you entered these. Can we say that I suppose?

JSG: I think if we were to say that I am the first historian in the region to apply the historical method consistently to a number of subjects and areas and to cover a very vast area of study, this would be factually accurate. This has been made possible not by me alone but by kind friends and other enlightened people who appreciated the work which I was doing, which I have been doing, and that is the reason why I could be invited to the Punjab University, I was invited to the Guru Nanak Dev University, and invited to the Punjabi University. I didn’t try for those jobs. It doesn’t mean that I have never tried for any job or got everything. This is not the case. But in these cases, certainly, they were kind enough to invite me, good enough to invite me, appreciating the work which I have been doing.

KM: Who are the historians with whom you have interacted very closely?

JSG: I look back to the days before I took up history or why I took up history, then Dr Kaul I mentioned. That was one person who influenced my life in a way—in a big way because the question of research and my going abroad was largely due to him. And also his general attitude, friendly towards those students who were serious. And he remained a lifelong friend though he was my teacher. Then…

KM: Prof. Peter Hardy.

JSG: Prof. Hardy was my supervisor. That was a formal relationship but informally it was wonderful. As I mentioned earlier, he spent a lot of time, took a lot of interest and he remained interested in whatever I wrote later on. I also met him whenever I went to the UK. So I am indebted to him very deeply.

KM: Prof. Nurul Hasan.

JSG: Prof. Nurul Hasan was very kind because I did not know him in any other way. In fact, I recall that I requested to see his thesis at Oxford and he didn’t allow me, not knowing who I am. Then after joining Delhi, I went to attend the first history conference, Indian History Conference (Congress), and then I gave a paper; Prof. Nurul Hasan was present there. He liked the paper. And therefore, he started taking interest in what I was doing. Throughout his life then he was very kind, taking interest, encouraging.

Prof. Mishra at Baroda, we had a very good relation, personally, and also because of our interest in history. For several years we met regularly and talked about small small things. And I think I learnt a lot from him. A very serious historian and very competent.

IB: I think it has been a great privilege and a pleasure for us to have talked to you and it has been a learning experience as ever.

JSG: Thank you very much.

IB: I am sure through Sahapedia your ideas would reach out to students and scholars everywhere. And we wish you a productive, long life.

JSG: Thank you very much. Thank you.