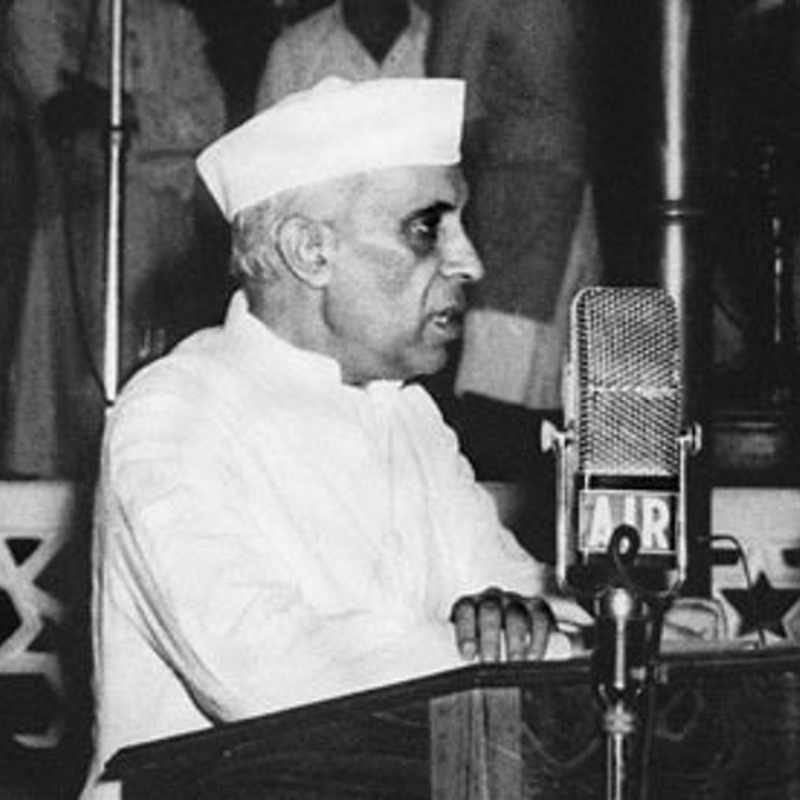

Whenever independent India’s film history is written, Jawaharlal Nehru’s name undoubtedly comes to the fore. The first prime minister of India not only initiated national policies but influenced the creativity of a host of film-makers as well. We explore Nehru’s contribution to the Indian film industry. (Photo Courtesy: Public Domain)

The first prime minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, is known for his development model and how it shaped the country. However, a little-known aspect of his contribution to India is in the field of cinema. Nehru was a cinephile who not only played an integral part in the emergence of Bollywood, but also supported and encouraged the genre of ‘films with a message’.

Aruna Vasudev, a documentary film-maker and an eminent scholar on Asian cinema, wrote in The New Indian Cinema (1986) that, until 1951, cinema was ‘treated at worst as a reprehensible, though unavoidable, social catastrophe, at best a barbarous pastime for the uncultured’ and gave the entire credit of the development of Indian film industry to the Film Enquiry Committee (FEC) set-up by Nehru in 1949. The committee examined the state of the film industry and proposed measures to further its development along desirable lines.[i]

Under Nehru’s leadership, the government laid the foundation for cataclysmic changes in Indian cinema, which included the formation of the Film Finance Corporation (FCC) in 1960 and the establishment of the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) in 1960 (Courtesy: Public Domain)

While the government focused on the development of post-Independence India, Nehru did not fail to include the film sector in his vision. Based on an FEC report, he called for a national film seminar in 1955. With B.N. Sircar as the chairman, Devika Rani as the executive director and Prithviraj Kapoor as the director, the six-day seminar offered recommendations on institutional changes to alter the course of film-making in India—including training, archiving and funding—as also to attract new talent.

Films, Development and Diplomacy

While some saw cinema as a catastrophe, Nehru viewed it as a tool for education and a means to develop the country’s identity. In January 1952, during his inaugural speech at the first International Film Festival of India, Nehru stressed the need for more cultural intervention in the field of films. He said:

Film has become a powerful influence in people’s lives. It can educate them rightly or wrongly… I mean that they should introduce artistic and aesthetical values in life and encourage the appreciation of beauty in all its aspects. I hope that films which are just sensational or melodramatic or such as make capital out of crime, will not be encouraged. If our film industry keeps this ideal before it, it will encourage good taste and help pave its own way in the building of a new India…[ii]

Nehru realised the need for aligning the Indian film sector with the best global trends, and, in 1951, invited Parsi polymath and film-maker Jean Bhownagary to be the information adviser to the newly formed Indian government. In fact, it was Bhownagary who organised the first international film festival in 1952. To further his vision of promoting Indian creative arts through cinema, Nehru then brought in British film scholar Marie Seton—an old associate of Nehru’s confidant, V.K. Krishna Menon.

Seton landed in India in the summer of 1955 and played a major role in the governmental acceptance of Satyajit Ray’s first film Pather Panchali (1955). She became Nehru’s eyes and ears in the Indian film sphere, and was a friend to his daughter, Indira Gandhi. She lectured on film appreciation across the country, discussing the emergence of Indian films on the global map. She also unified sporadic film society activity under the Federation of Film Societies of India (FFSI).

Under Nehru’s leadership, the government laid the foundation for cataclysmic changes in Indian films over the decades. This included the formation of the Film Finance Corporation (FCC) in 1960 (which became the National Film Development Corporation [NDFC] in 1975), the establishment of the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) in 1960 and the formation of the National Film Archives of India in 1964. ‘With the FFC’s policy decision in 1968 to start giving loans to new film-makers for “small budget, offbeat” films, the means of production were radically expanded and the ground work for arrival [sic] of alternate cinema was laid,’[iii] Vasudev wrote in her book.

Nehru not only initiated policies but influenced the creativity of a host of artists in film-making as well (In pic: Jawaharlal Nehru with Prithviraj Kapoor, B.N. Sircar and Devika Rani; Courtesy: V.K. Cherian)

Ever the statesman, Nehru was skilled in using the appeal of film stars as a tool of diplomacy. He would often ask K.A. Abbas, Prithviraj Kapoor, Raj Kapoor and Nargis to be a part of cultural delegations abroad. Fuelling the fascination for Indian films in countries such as Russia and Egypt, the inclusion of members of the film fraternity in these delegations was significant for international diplomatic relations.

Nehruvian Ideals in Cinema

‘Apart from the policies relating to films, the Nehru’s [sic] “occidental” impulses in bringing modernity to the traditional society emerging from the yoke of colonialism influenced themes in films of people like K.A. Abbas and Chetan Anand in 1950s,’[iv] said Darius Cooper, professor of literature and film in the Department of English at San Diego Mesa College, USA. He focused on two films from 1954 that literally presented ‘Chacha’ or Uncle Nehru to a younger generation, showing how children responded to the Nehruvian utopia of the first Five Year Plan. In Raj Kapoor’s Boot Polish, the orphaned brother and sister go from the shameful act of begging to the more honest activity of polishing shoes. This symbolised Nehru’s vision for the inclusion of all marginalised communities in Indian society. Similarly, Chetan Anand’s Taxi Driver represented the maligned Anglo-Indian community as actual characters in the film’s narrative. Even Shri 420 was a ‘weak stereotypical critique of Nehru’s urbanised progressive schemes’.[v]

Thus, Nehru not only initiated policies but influenced the creativity of a host of artists in film-making as well. When Nargis attacked Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali for selling Indian poverty abroad, Nehru justified the film’s ‘poverty portrayed with empathy’, earning Pather Panchali acceptance across the nation. All these decades later, Ray’s debut film is still widely recognised among the 100 best international films of all time. Indeed, Nehru inspired and promoted a generation of creative artists in independent India, many of whom, like Ray, went on to make their mark on the global map of films.

This article was also published on Firstpost.

Notes

[i] Aruna Vasudev, The New Indian Cinema (New Delhi: Macmillan, 1986).

[ii] Mridula Mukherjee, The Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru (New Delhi: Oxford University Press India, 2009) 311.

[iii] Aruna Vasudev, The New Indian Cinema (New Delhi: Macmillan, 1986).

[iv] Darius Cooper, ‘Hindi Cinema’s Nehruvian Yatra,’ Journal of Indian Film Culture (June 2012).

[v] Ibid.