Introduction, by Debleena Tripathi

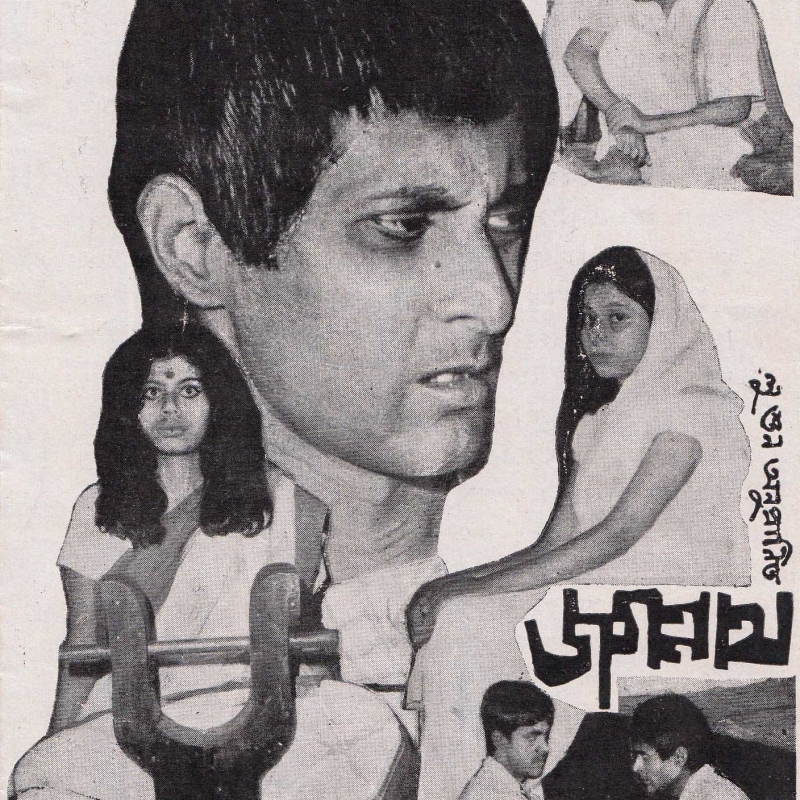

Jagannath, an adaptation of Lu Xun’s Chinese novella, The True Story of Ah-Q, directed by Arun Mukhopadhyay and produced by Chetana in 1977, is now a legendary production of Bengali theatre. The master storyteller, Arun Mukhopadhyay had borrowed the basic storyline from the novella, and added to it by reworking and Indianising it. Mukhopadhyay’s Jagannath is a poor, uneducated villager:

“. . . [B]y nature he was cowardly, inherently lazy. All the villagers disregarded him and people of higher ranks did not even consider him to be a human being. No matter what wrongful or unjust treatment he was subjected to, there was no inclination in him to protest or resist. He was used to accepting everything silently—a slavish mentality was ingrained in him” (Mukhopadhyay 1987, 120-121, translation mine).

Jagannath is beaten out of his job at the zamindar (landlord) Das Babu’s residence after he boasts somewhere that he being a ‘Das’ too, is related to Das Babu. His arch-enemy Nanda gets the job. Nanda is the only person Jagannath can fight with, openly. He accepts his humiliation at the hands of Das Babu and others of his rank, but cannot do the same for Nanda, as he marks Nanda as one with a status similar to him.

Jagannath fails repeatedly. He cannot stand it when he is teased mercilessly at the local bar. Nalini, the widowed daughter of thakur-moshai (the priest) proposes to him and he fails to respond. When his childhood love Monoroma, who works at Das Babu’s place too, is approached by the lecherous Das Babu, Jagannath runs away. Even when Nanda stands up against Das Babu, and the villagers promise to stand by him, Jagannath cannot agree to participate.

Like the original Ah-Q, Jagannath Das has a strange procedure of shaking off all humiliation and scoring psychological victories over his opponents. Even when he has a real gun in his hand, he only fantasises about frightening his oppressors. The little that he does in real life, ironically, is only to spite Nanda. He agrees to marry the pregnant Nalini because, as he exclaims, Nanda would not dare to father someone else’s son. He attempts to lead the villagers to protest against Das Babu, only when he sees that people consider Nanda to be a hero for attempting the same. He boasts about the revolutionaries taking shelter in his house, when Nanda’s alleged association with revolutionaries is celebrated. Jagannath is arrested as a revolutionary and he is ecstatic about it, until he realises that he is going to be hanged. But then again, the news that Nanda has shot Das Babu, and that there is a reward on Nanda’s head, leads him to his last psychological victory. Nanda fails to ‘achieve’ a hanging, and in that failure, Jagannath succeeds.

Unlike Ah-Q, Jagannath is never lacking in compassion. The tale of Jagannath, with its little acts of kindness and love, is much more humane than that of Ah-Q. Jagannath weaves a mora (a stool made of rattan) for Monorama. Monorama requests Nanda to carry her share of muri (puffed rice) for Jagannath. Jagannath brings home a toy pistol for Nanda’s son. And Barun, the revolutionary, who hails from the same village as Jagannath Das, attempts to write about Jagannath.

Indeed, this is what makes the narrative in Jagannath exceptional. Barun’s narration is again peppered by Jagannath’s commentary, where he points out in his own way that Barun’s approach to his life is inadequate and unnecessarily dramatic. It is interesting to see how the revolutionaries, who are fighting for the freedom of their countrymen with undoubtable sincerity, fail to fathom the common men like Jagannath. Barun admits that he is at a loss, trying to understand Jagannath’s aspirations. Jagannath, on the other hand, puts all his effort in defeating Nanda—an act of 'horizontal violence' (Freire 1921:62), rather than trying to destabilise his ‘superiors.’ This lack of understanding transcends time and makes Jagannath as relevant even today, as the intellectual leaders still fail to represent the masses.

'I do not know Jagannath Das well, but I know my class,' says Arun Mukhopadhyay (Mukhopadhyay 2014). He remains true to the limits of his lived reality by employing the character Barun, and yet, stretches out, without offending or appropriating.

Jagannathaswami Hridayapathagami - Jagannath as the Way to One's Heart

A Personal Response to the Play, by Goutam Kumar Sarkar

When the playwright, the director, and the actor are one and the same person, the play grows into a complete being where you cannot say that the very same text could have turned into a different theatre experience if we had a different actor to play the lead. This is what Arun Mukhopadhyay claimed in an interview (Kaahon Wall 2015) that the ‘elemental’ humanity and emotion in Jagannath could be played by any actor per se. With all due respect to Arun-da, the best actor living in Bengali theatre, I cannot agree with the view on several counts.

I watched Jagannath, for the first time, around 1982 or 1983. All I can remember about the play is how intensely Arun-da lived every moment on the stage, how he had squeezed the space to a lover’s inner world of dream at one moment, and in another he stepped into the world, to allow perspectives of the onlookers and the society at large, of which the same lover is a part himself. Here a very delicate balance is to be maintained: on the one hand, there are the personal longings, cherished by the frail individual in a material world, always at the threat of being trampled on by habitual cruelty; on the other, there is the world itself with all the conflicting aspirations of its inhabitants to find freedom and yet maintain the status quo. Arun-da achieved it through the wonderful sense of humour that ran all through the tenet of the play. His satire never came on too strong but instead sent us a gentle reminder that all our individual actions have some effect on the world around us; they either add to the hostility and injustice of the world, or seek to change the situation for the better.

The more skeptical we grow over the years about the possibility of the general well-being of all humanity, the more nostalgic we grow for an individual to hold on to his faith and at the same time, with a wry smile, jeer him on to his doom of self-immolation. Even then, in Jagannath, we could not just snidely laugh. We leave the theatre with a sense of bewilderment. When Jagannath was performed for the first time, West Bengal had still kept some hope in a partial form of socialism. The Left Front came into power, held its sway for an unbelievably long period of thirty three years and got itself wiped out through a process of gradual degeneration. However, it left the legacy of mass corruption and civil unrest. Once again, after a hollow promise of the Congress in the wake of freedom, the country woke up with a jolt to a darker night of complete chaos and disintegration.

Jagannath, through its first performance up to its revival in the new millennium, spanned across not just this change of political scenario, it covered a journey for Arun Mukhopadhyay as well. An ardent believer in the institutionalised Left, his plays tried to find a new resonance in Manik Bandyophyay. His stage adaptation for Taking Sides (Apni Kondike, 2005, based on Ronald Harwood’s play and inspired by Hungarian director Istvan Szabo’s film by the same name) serves perhaps as a watershed in-between: the judge and the accused meeting on the common ground of some basic questions involving the moral code of existence. As an honest theatre artist, Arun-da kept himself busy with keeping track of the changing attitudes in content and form; he did not, as many of the aspiring young directors of the new millennium do, spice his productions with out-of-context songs and dances to guile the audience with a false flavour of the folk.

He searched for the folk within. In his Nirnoy, an adaptation of David Auburn’s play Proof, the principal character seeks to know whether her talent is inherited or acquired—the journey, provoked by the external circumstances, is pursued within. The best of our folk tradition is woven around the same spindle. We need not scratch under the skin of the tramp in search of a metaphor, the tramp himself is destined to find a Chaplin on the way.

Having said that, the question remains: who, as an audience is supposed to respond to such an honest enterprise of a director, who is also the playwright and an actor himself? In a fast growing consumer-driven world, our best adventure is a tryst with what Noam Chomsky might have called ‘a tolerable reality’ (Chomsky 2011) spawned in Hollywood films and of course, in their wake, in Bollywood, trickling down to the Tollygunge Studio. The rough, raw, stark and the turbulent in Ritwik Ghatak’s Subarnarekha (cult Bengali film, released in 1965) would now only be appreciated by a handful of anaemic movie buffs sprinkling their pearls of wisdom in the Sunday pages of the third rate dailies. The media will create icons of the mediocre; the rising decibel of TV ads and soaps will drown out every sincere, honest and gentle musing in the monologue of the soul. Jagannath, in 2018, would be a wonderful myth unless, as I would once again assert in complete disagreement with Arun-da’s claim, it can only be played with Arun-da, and Arun-da alone, in the lead role.

References

Chomsky, Noam. 2011. Media Control: The Spectacular Achievements Of Propaganda. New York: Seven Stories Press.

Freire, Paulo. 2005. Pedagogy of The Oppressed. London: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc.

Kaahon Wall. #Kaahonperformingarts—Arun Mukherjee. On Revival of Jagannath, Bengali Theatre. YouTube. 2015. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zG_1aH5z5SI&t=300s)

Mukhopadhyay, A. 1987.‘Jagannath.’ Group Theatre, Year 3, Issue 2/3 including Jagannath Supplement.

Mukhopadhyay, A. 2014. “Arun Mukhopadhyayer Songe Anshuman Bhowmick”. Interview by Anshuman Bhowmick. Sayak Natyapatra Sakkhatkar Sonkhya, 12(20)