Bagori is one of the many villages that flourished along the banks of river Bhagirathi in Uttarakhand, India. It is an unexplored trans-Himalayan settlement tucked away in the Garhwal Himalayas en route to the Gangotri shrine. The settlement can only be accessed by foot or on two-wheelers from Harshil, an adjoining village. (Fig. 1) The remote location of the village has helped it remain unexploited by the massive tourist and pilgrim influx.

One can see Tibetan prayer flags fluttering on the bridges that lead to Bagori. These hint at the probable Tibetan cultural influence on the village. On crossing the village gate, before the settlements begin, there is a temple dedicated to Lal Devta, a local deity, and a Buddhist monastery on either side of the street. (Fig. 2) People in this village follow both Buddhist and Hindu religious beliefs and practices. As one walks through the village, a stark linear arrangement of the houses can be seen. The houses are made with locally available materials like Deodar wood and stones. They are built with an indigenous building method (timber-reinforced stone masonry), an adaptation of the popularly known koti banal construction technique in Uttarakhand or kath kuni in Himachal Pradesh.

The Jadh-Bhotiyas: Etymology, History and People

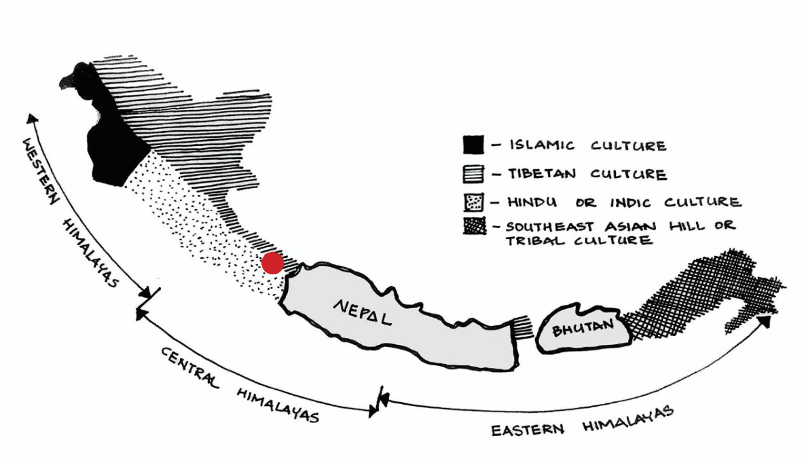

Bhotiyas are an ethno-linguistic tribe that reside along the trans-Himalayan belt of the Himalayan range.[1] (Fig. 3) They inhabited the high-altitude regions of the Indian Central Himalayas at the Indo-Tibetan and Indo-Nepal borders. The Bhotiya communities were mainly traders and pastoralists involved in multiple occupations allied with the processing of wool. In the Tibetan language, the word ‘Bod’ means Tibet (pronounced as Bho or Pho). Earlier, it was associated with the traders coming in from Tibet, who were called Bhotiyas, which referred to the people from across the border or people from Tibet. The terminology is now carried forward by the Bhotiya communities of the trans-Himalayan belt, who are mistaken as Tibetans for their Mongoloid appearance, cultural similarities, proximity of their earlier settlements to the Indian border, and trade with the Tibetans.[2]

People living in the Bagori village identify themselves as Jadh Bhotiyas/Bhotias. They are a semi-nomadic tribe that resided in the high valleys of the Bhagirathi river system of the Uttarkashi district in Uttarakhand, India. The original settlement of the Jadh Bhotiyas living in the Bagori village was in the Nelang and the Jadong Valley, at an altitude of over 3819 meters, on the Jahanvi (or Jadh Ganga) tributary of the Bhagirathi River. Due to their proximity to the river Jadh Ganga, they were recognised as Jadh Bhotiyas, meaning ‘Bhotiyas of the Jadh River’.[3]

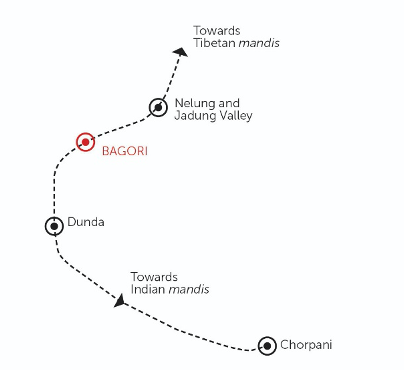

They followed seasonal transhumance primarily because of their occupation (pastoralism), and also due to the extreme climatic conditions in the high Himalayan valleys. In the summer months (from April to October) they stayed in the Nelang-Jadong valley and carried out trade with the Tibetan traders. Across the borders, they bartered goods like wool, borax and salt obtained from the Tibetan mandis (markets) for sugar, grains and woollen products in the Indian mandis and vice-versa. During the extremely cold months from October to April, the community migrated to Dunda village and sold their goods in the mandis in the Indian plains. Those with large number of sheep and cattle migrated to Chorpani, near Rishikesh, for grazing.[4] (Fig. 4)

After the 1962 Indo-China War, the Indo-Tibetan trade ended and the Jadh Bhotiyas were relocated from the Nelang-Jadung valley. They have now resettled in the village of Bagori, located downstream on the banks of the Bhagirathi River.

Bagori was a part of the Indo-Tibetan trade route and was used by the Jadh Bhotiyas as the last camping site before reaching the high mountain valleys of Nelang and Jadung. In addition to this, the village Bagori was situated on the old pilgrimage route from Uttarkashi to Gaumukh and was accessed by the pilgrims on foot. Prior knowledge, familiarisation and association to the place was the main reason for the Jadh Bhotiya community to resettle at the Bagori village. Another contributing factor was that the then existing Pahari community of the Bagori village welcomed and accommodated them.[5]

The Jadh Bhotiyas still follow seasonal transhumance, but this is mainly due to extreme weather. During summers, they stay in Bagori and in winters they migrate to Dunda or other cities like Haridwar, Rishikesh, or Dehradun.[6] Today, very few people from the community own sheep and cattle. Since their relocation and an end to the Indo-Tibetan trade, most people in the village have given up pastoralism and have adapted to agriculture as their main occupation. The Harshil-Bagori valley is now famous for its apple orchards and rajma plantation. The older generation living here is still involved in the occupations related to sheep shearing, carding, spinning and weaving. However, the younger generation have moved out of the village for job opportunities and further education; they are not associated with any activity related to sheep rearing. Today, many houses in the village are abandoned and unoccupied and lie in a dilapidated condition.

Geographic Location and Pattern of the Settlement

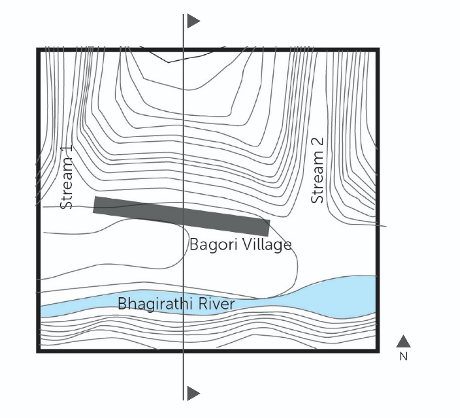

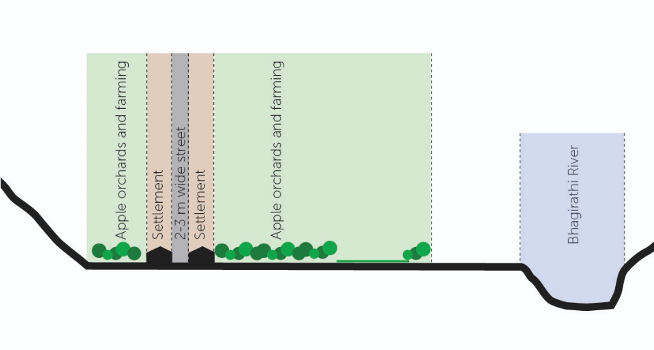

Bagori village is situated in one of the wide valleys of the Uttarkashi district of Uttarakhand. To the north of the settlement are steep mountain slopes, whereas on the south is the Bhagirathi River. The east and west of the settlement is flanked by steep narrow valleys formed by seasonal nallah (stream). (Fig. 5) The village has flourished within these confined geographical limitations. The flat land of the wide valley, gently sloping towards the river facilitated the settlement of this community. The houses are not scattered, but arranged linearly along the street that runs parallel to the river and the contours. (Figs 5 and 6) In order to protect themselves in case of flood caused by overflowing of the river or torrential rains, the village has a buffer of 160–200 m from the river edge. (Fig. 7)

Unlike the houses in the mountainous region which are scattered along the different contours of this hill, the houses in Bagori are individual isolated units, adjacent to each other at a distance of 1–1.5 m for circulation and accessibility. They are strategically placed such that the house does not fall under the shadow of the adjacent house and gets ample sunlight. (Figs 8 and 9)

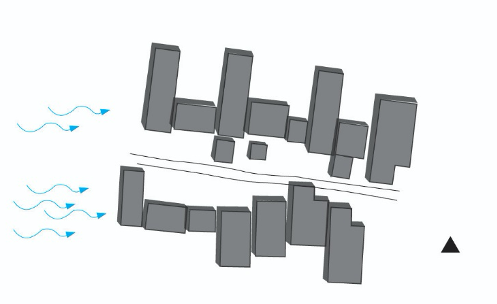

Most of the houses on either side are arranged perpendicular to the street to capture maximum sunlight from the south and southeast directions. As the wind direction is mainly from southwest and south directions, the surfaces of the houses facing this direction does not have openings. Blank walls stop the cold winds from entering the house and also act as a factor that gives privacy from one house to the other. (Fig. 10)

The houses earlier did not have any boundary walls and opened out into the street. Today, the houses have a boundary wall in the front and sides regulating entry from the street. The front yard acts as a communal space for interaction, where women usually gather for spinning wool, knitting and other social activities. (Fig. 11) The backyard of the house extends into a kitchen garden.

House Form and Spaces

The house form, its spatial configuration and construction technique are a unique knowledge that the community has brought from the valleys of Nelang and Jadung. (Figs 12 and 13) It is an outcome of the community responding to the influencing factors like topography, climate (rain, snow, sun and wind), occupation (pastoralism and agriculture) and the need for social spaces. While the construction technique is quite similar to that of koti banal and kath kuni, it is distinct in multiple ways. Unlike the typical koti banal house that have load-bearing walls from the ground level, the houses in Bagori are raised on stilts/columns made of stone or a combination of both stone and wood. The height of the house is limited to only one storey and do not go any higher. The roofing material is wood instead of slate finish as seen majorly in other regions. They have less or no projections of balconies and roof.

Changes and Challenges

The Jadh Bhotiya settlement is an outcome of understanding the various factors that have helped shape the settlement pattern and house form. In the past, there was an understanding of the local material and construction technique accommodated as per the requirement of the Bhotiya community. This knowledge has been passed down several generations. However, today, there are no masons available in the community to carry forward the traditional skills and knowledge. After the ban on the trade across the borders and due to lack of other opportunities in the region, the younger generation of the Bhotiya community have migrated. This has resulted in abandoned houses that lie in dilapidated condition. Those living in the village are reconstructing their houses with new construction materials and technology, because they are unable to keep up with the maintenance of such houses due to lack the knowledge of traditional construction techniques. Moreover, for more economic opportunities like making a homestay, the old houses are being torn down and reconstructed using contemporary materials. (Fig. 15) The village is transforming at an alarming pace and the old materials are being replaced with the new materials, resulting in the loss of traditional knowledge and skill. With time, traditional construction practices are becoming extinct due to the appalling lack of awareness, patronage, workmanship and government policies. At this rate, the village stands a high chance of losing its authenticity and identity in the near future. It is, therefore, crucial to document and understand the factors that led to the peculiar construction techniques of the community and to generate sensitivity and create awareness about their resources. It is also equally important to encourage the locals to preserve their traditional knowledge and construction techniques.

Notes

[1] Sherring, Chas A, ‘Western Tibet and the British Borderland: The Sacred Country of Hindus and Buddhists.’; Bergmann, Gerwin, Nüsser, and Sax, ‘Living in a High Mountain Border Region: The Case of the ‘Bhotiyas’ of the Indo-Chinese Border Region.’

[2] Stein, Tibetan Civilization, 30–31.

[3] Chatterjee, ‘The Bhotiyas of Uttarakhand.’

[4] Pant, The Social Economy of the Himalayas; Nand and Kumar, The Holy Himalaya: A Geographical Interpretation of Garhwal; Negi, Discovering the Himalaya; Jain and Singh, ‘Sustainability and Traditional Buildings.’

[5] Oral Testimony Programme of the Panos Institute, Panos' Oral Testimony Programme, accessed October 10, 2019, http://mountainvoices.org/india.asp.html.

[6] Ibid.

Bibliography

Bergmann, C., Gerwin, M., & Nüsser, M., Sax, W.e. 'Living in a High Mountain Border Region: the Case of the ‘Bhotiyas’ of the Indo-Chinese Border Region. .' Journal of Mountain Science 5 (2008): 209–17. doi:10.1007/s11629-008-0178-9.

Chatterjee, Bishwa B. 'The Bhotias of Uttarakhand.' India International Centre Quarterly (India International Centre) 3, no. 1(1976): 3–16.

Dash, Chittaranjan. Social Ecology and Demographic Structures of Bhotias. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, 2007.

Hoon, Vineeta. Living on the Move: Bhotiyas of the Kumaon Himalayas. New Delhi: Sage Publications, 1996.

Kumar, A., and Pushplata. 'Vernacular practices: as a basis for formulating building regulations for hilly area.' International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment. 2013.

Langenrbach. Don't Tear it Down. UNESCO, 2009.

Negi, S.S. In Discovering the Himalaya (Vol. 1), edited by M., & Singh, I. Jain. New Delhi: Indus Pub. Co., 1998.

Rautela, P., and G.C. Joshi. 'Earthquake safety elements in traditional Koti Banal architecture of Uttarakhand, India.' Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 18, no. 3 (2009): 299–316. doi:10.1108/09653560910965655.

Samal, P.K., PP Dhyani and M Dollo. 'Indigenous medicinal practices of Bhotia tribal community in Indian Central Himalaya.' International Journal of Traditional Knowledge 9, no. 1 (2010).

Saraswat, S., and G. Mayuresh. 'Koti Banal Architecture of Uttarakhand: Indigenous Realities and Community Involvement.' Research into Design for Communities 2- Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies (2017): 165–77. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-3521-0_1.

Sharma, D. Nelang Valley, Medium. July 1, 2016. Accessed January 10, 2020. medium.com/@dhruv.sharma/nelang-valley-82d15bd2d82.

Sherring, Chas. A. Western Tibet and the British Borderland: The Sacred Country of Hindus and Buddhists. London: E. Arnold, 1906.

Singh, N, and G. Singh. 'Learning from Built Environment of Hill Region of Uttarakhand, India and its Response to Disaster Risk'. Paper presented at the 4th International conference on Architecture and Civil Engineering (ACE). Singapore: Global Science and Technology, 2016.

Singh, N., R. Pasupuleti and A. Khare. 'Disaster Risk Reduction through the learning of traditional knowledge of built heritage- a case study of village Bagori, Uttarkashi, India.' Paper presented at the 10th FARU International Research Conference. Wadduwa, Sri Lanka, 2017.

Stein, R. A. Tibetan Civilization. Stanford University Press, 1922.

Thakkar, J., and S. Morrison. Matra - ways of measuring vernacular built forms of Himachal Pradesh. SID Research Cell, CEPT University, 2008.