From cave paintings and murals to painted photographs, portraits in India have undergone a massive change over a period of 30,000 years. Sahapedia.org and DAG trace the influences and transformations in the tradition of portrait making in the subcontinent. (Photo courtesy: DAG)

While the development of portraits in India as we know it can largely be attributed to British colonisation, the practice of self-documentation—in the context of the world around us—is as old as humanity itself.

Around 30,000 years ago, human beings living in the rock shelters of Bhimbetka (Madhya Pradesh) drew images of celebrations and of themselves as hunters and villagers on cave walls. Jumping back 4500 years to the Indus Valley civilisation, we have the iconic sculptures of the Dancing Girl and the Priest King. While the former is often casually referred to as the ‘first red-carpet pose’, the latter is arguably one of the first busts we know of.

Also read | In Memory of Ramkinkar Baij: A Grassroots Modernist Artist

Closer home and closer in time

The tradition of portrait making in the subcontinent is a continuing practice, one where the divine and the human often coexist. For example, the walls and ceilings of the Ajanta caves (second century BCE onwards) are teeming with images of the Buddha, bodhisattvas and humans alike. Hindu temple façades have a series of projections and recessions decorated with relief sculptures; while gods are placed on the projections, human figures are seen in the depressed spaces. Jumping to the sixteenth century, the art of portraiture, in the form of the miniature tradition, began to thrive in the Mughal Empire. Govardhan and Basavan were famous artists in Akbar’s court, while the latter’s son, Manohar Das, worked for Jahangir.

Also see | The Unlikely Voyage to India that Inspired Over 100 Paintings

The principal shift in Indian art came with the advent of British rule (eighteenth to nineteenth centuries onwards). Following the failed 1857 uprising, a number of art schools were established. These institutions—in Madras (now Chennai), Calcutta (now Kolkata), Bombay (now Mumbai) and even Baroda (now Vadodara)—taught European naturalism to locals in order to later employ them to document the local landscape and demography. Over the course of the schools’ existence, the agenda gradually shifted to a complete focus on fine arts, with each site developing its own unique style.

The British invasion saw the arrival of European travelling artists such as J. Barton and Benjamin Hudson. On the one hand, these artists painted portraits of local royalty, English officers as well as British royalty, while on the other, artists such as F.B. Solvyns, James Wales, and Thomas and William Daniell conducted topographical and ethnographical documentation for the people back home.

The rising popularity of European naturalism in nineteenth-century portraiture effected a decline in pre-existent indigenous art. As a result, local artists such as Raja Ravi Varma (mainly known for his oil on canvas paintings, especially of Hindu deities) began painting using European techniques.

Contemporary portraiture

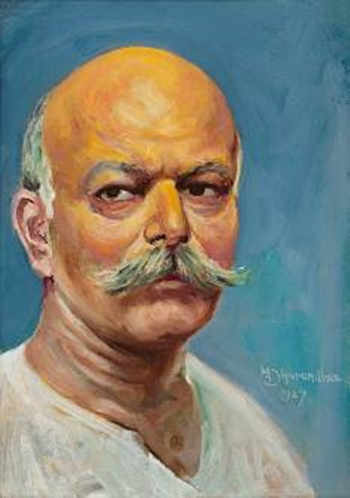

Among the four major art schools/centres, Ravi Varma’s work at the Sir J.J. School of Art in Bombay gained popularity, plausibly because he was running a printing press in Lonavala at the time, which allowed for a higher degree of movement of his prints. M.V. Dhurandhar, J.D. Gondhalekar, S.L. Haldankar, P.T. Reddy, Abalall Rahiman, N.R. Sardesai and M.F. Pithawalla are a few painters from the school who mastered the art of portraiture. Of these, Dhurandhar—who is regarded as the most important artist of this generation—was directly influenced by Ravi Varma. Additionally, Pithawalla gained fame by painting portraits of men and women from wealthy Parsi business-class families.

Painting a photograph

A direct challenge to professional portraiture came with the advent of modern photography in 1839, thanks to the Frenchman Louis Daguerre. The daguerreotype arrived in India soon after, presenting a cheaper and quicker alternative to the painstaking process of painting a portrait. As a compromise, photo studios began working with artists, who would colour black-and-white photographs or even paint commissioned portraits from photographs.

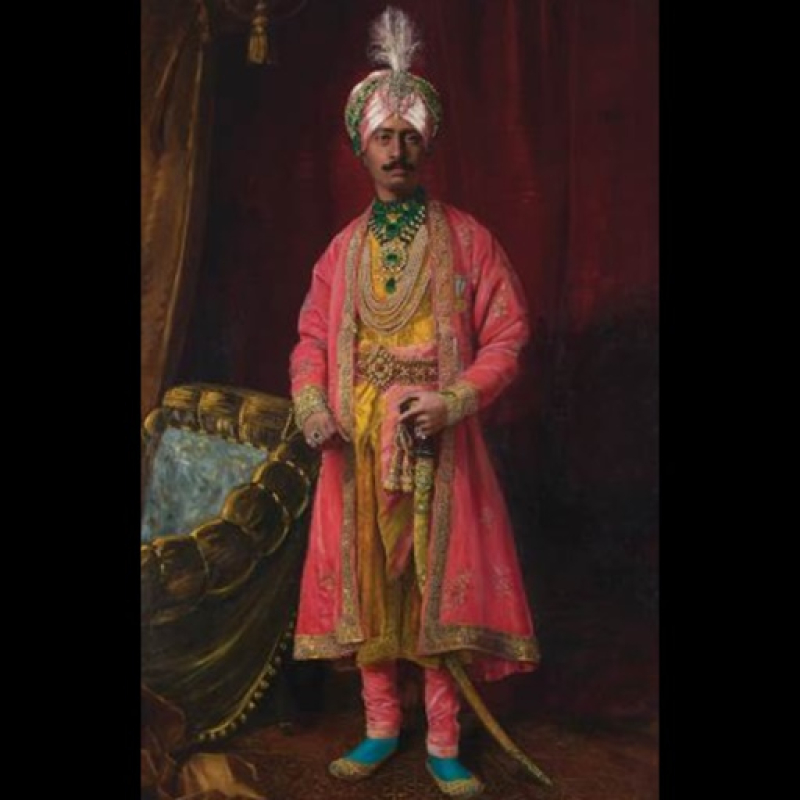

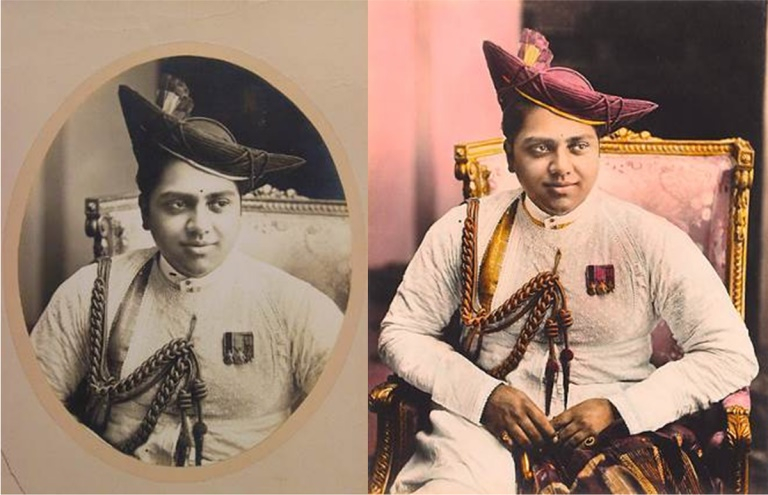

For instance, the striking portrait of Nawab Ahmad Ali Khan of Malerkotla (c. 1930) was painted from a photograph by the renowned Bourne & Shepherd studio. This painted reproduction is curiously signed in the studio’s name instead of the original artist(s). Sized at a massive 108 x 60 inches, with the original frame weighing over 200 kg, this painting is a stunning example of how painters and photography studios worked together. Other examples of this style are the photos of Maharaja Jiwaji Rao Scindia (1916–61) of Gwalior, which appear both as a black-and-white photograph as well as one hand-tinted with watercolours.

Stylised ‘selfies’

European naturalism also took a beating at the turn of the twentieth century. The onslaught of the two World Wars, the struggle for Indian independence and the development of modern artistic practices began to nullify the need for ‘academic realism' in art. Portraits became stylised, as can be seen in Paritosh Sen’s Self Portrait (dated 1948) and Sudhir Ranjan Khastgir’s Untitled portraits (c. 1950). The most striking of these examples, however, is Kisory Roy’s self-portrait, Art and Famine (c. 1944), painted at the height of the Great Bengal Famine of 1943–44.

After Independence, the centre of Indian art slowly but surely shifted from the colonial capital of Calcutta to the newer, more metropolitan city of Bombay. Academism and naturalism were seen as sedentary modes of expression. The struggle for independence, two World Wars and the financial and political struggles of the newly formed nation created anguish among the population. Artists reacted to this by transitioning towards art that was more expressive.

The Europeanised abstractionism of the Bombay Progressive Artists became a canon-forming identity of Indian art in the international market, while practitioners of the Madras School, led by stalwart K.C.S. Paniker, delved into the esoteric ideologies of tantric philosophies. Even though certain artists like Bikash Bhattacharjee continued to use certain naturalistic elements in their art, commissioned portraits had by then been relegated to the confines of history—the only true respect to the genre was shown in officially sanctioned images of prime ministers and presidents.

This article was also published on The Statesman.