HARADAS APPACHA KAVI- LIFE AND WORKS

INTRODUCTION

Folk and regional theatres have their own subtlety and aesthetics that have attracted researchers all over the world. Still, there are many such theatres in our country that have been pushed into oblivion due to lack of research. Theatre in Kodagu, a small district in Southern Karnataka in India is one such area which falls woefully short of critical assessment and appreciation.

Apparently, there exists a lack of awareness among the general public about Kodava Theatre. Even a cursory attempt at presenting a historiography of Kodava Theatre has been overlooked or unexplored against the rich backdrop of Indian theatre. This article will focus on the works of the great poet Haradasa Appacha Kavi of Kodagu whose works are the first available literature written in Kodavattakk, the native language of the Kodavas[1].

Kodagu district in the southern state of Karnataka nestles in the hills of the south-west coast of India. Kodavas, the people of Kodagu have their own language called "Kodavattakk" which incidentally, does not have a script of its own. Kodavas hold themselves as a race apart. They are– a tall, fair and warrior-like race whose origins are still being debated. They have their own unique culture, religious rites and rituals that bear some resemblances to the Hindu religion, but they do not like to be categorised as Hindu. The Kodavas are a close knit community that has its own unique culture and values quite distinct from the rest of Karnataka. This idea has recently spurred controversies in contemporary Kodagu, with a large part of the population demanding that Kodagu be given its own separate statehood owing to the aforesaid distinct cultural values.

Kodavattakk sounds like a conglomeration of South Indian languages belonging to the Dravidian language family and is influenced by or related to Tulu, Kannada, Malayalam and Tamil. On closer observation, one sees that Kodavattakk has become a “Linguistic Island” surrounded by much larger dominant languages and as such it currently faces a danger of extinction. The life of a language is governed by and is continually enriched by the literature it produces and by its usage in everyday life. When the literature starts deteriorating, the language begins to collapse. Considering this aspect, Haradas Appacha can be looked upon as the saviour of the Kodava language, since he produced the first ever written literature in Kodavattakk. Though he wrote just a handful of plays, in a period where it was indeed an arduous and ambitious, not to mention a highly expensive task to write and publish, his works are revered, respected and discussed to this day in Kodava literary circles.

EARLY LIFE

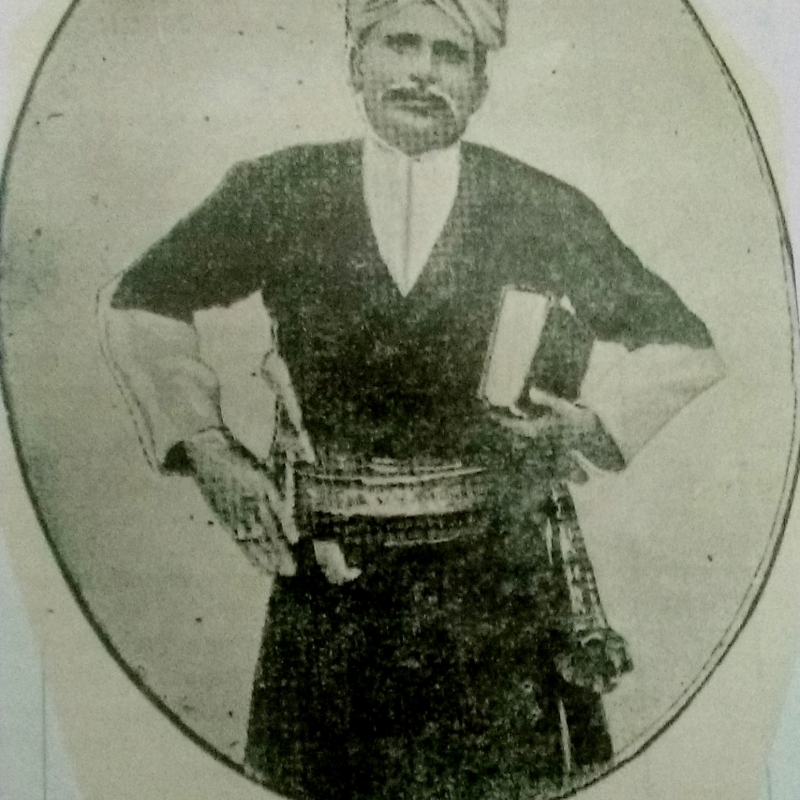

Appaneravanda Appacha, popularly known as Haradas Appacha was born into the Appaneravanda family to Medappa and Bollavva, in Kirndaad village of Virajpet Taluk inKodagu, in September 1868. He enjoyed happy, carefree years of his early life in his uncle’s house near Virajpet. His paternal grandfather was a great scholar, who had no sons of his own. Under his tutelage, Appacha learnt the basics of literature and Math. Even at the tender age of seven, he could recite many verses from the Jaimini. While it looked like Appacha’s early formal education was about to suffer, he was fortunate to have Savitramma, a Brahmin lady who took great interest in Appacha and along with her son Subbaraya, patronised his education. It was from her that he learnt the Amarakosha, the Sanskrit Thesaurus which was of great help to him in his later years as a poet. When he was eight years old, his uncle enrolled him in a Kannada school. In 1878, though his father sent him to an English school to study the English language, he could not progress much in English education due to ill health in his childhood.

During those days, educational facilities were very inadequate in Kodagu and it was difficult to access schools from far flung villages. Thus Appacha was only able to study up to class IV. Appacha made good use of most of the available facilities and steadily picked up whatever he could grasp. Even in early childhood he displayed a keen interest in music and literature. After school hours, he used to visit learned men in the village and listen eagerly to the stories from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Bhagavadgita, Vedas and Upanishads. The exposure to classical music from an early age helped create a rhythmic style and melody to his later literary creations. Appacha joined the Virajpet village office as a volunteer from 1886 to 1888 which involved quite a lot of copy writing. He later quit that job and worked in the Mujrai department of the district administration. He then joined the Omkareshwara temple in Madikeri as a temple administrator. There, in the company of Brahmins and pundits, he extensively studied Kannada and Sanskrit literature.

The Kodava community has had a very complicated history and had witnessed many changes over the turn of the century. The British rule brought with it the English education system and other aspects of modernity. The crisis of the traditional Kodava society as a result of the advent of modernity was addressed by Haradas Appacha, who highlighted these issues in his creations time and again through his satirical and humorous interventions. His plays critique modernity and chide the citizens of pre independent Kodagu who allowed themselves to be transformed by, and take pride in the unabashed imitation of western cultural practices. This problem is highlighted by Haradas Appacha against the backdrop of traditional Kodava patriarchic values deployed with a greater element of the quotidian, spiced up with fine rustic sense of humor.

ELEMENTS OF FOLK AND RITUAL

The fact that Haradas Appacha’s plays are the first written materials available on theatre in Kodagu, poses another important question: What was the cultural scenario of Kodagu before the ‘era’ of Haradas Appacha. The knowledge of what existed before him is almost obscure. As most theatrical forms have their origin in folk forms, in looking at the origins of Kodava theatre, it becomes necessary to explore how Haradas Appacha’s plays might have been influenced by folk forms from Kodagu. The form that prima facie bears a resemblance is the [2] “Bodnamme” festival during which the performers dressed in various rustic makeshift costumes perform what is called the “Bodokali”. After the harvesting season, these performers go singing from house to house, making satirical performances, complete with acting, music and drums, a chorus, and use oil lamps and torches during the night. The villagers sit all around, listening to the performers cracking vulgar, ribald jokes, creating improptu satire on the dominant class or the rulers they despise, all in the name of God. In this spontaneous folk performance the formation of a complete theatre space becomes evident. Similarly folk songs like “Balopattu” and folk dances like “Bolakkattu”, the “Poonjolemaaye” songs that are sung during the “Joyipaattu” section of the “Huthhari” (harvest) festival are interspersed with theatrical elements from where Haradas Appacha might have borrowed his style.

In South Kodagu, there is a performance of the "Bekkesudlur Mandattavva" (a local name for Goddess Parvati) which takes place in a sacred space with a big fire pit. During a period of seven continuous nights many rustic plays are performed there in an overt style of mockery. Instances of births, deaths, rituals, and other major events in the villages in the current year are imitated in an entertaining way. Nobody leaves the performance space once they enter it because the audience is likened to a devotee who must sit through the worship of the Lord, in this instance the performance for Goddess Parvati. Hundreds of people gather around the fire. Such performances, that are rooted in the folk imagination act as clues as to the beginning of Kodava Theatre.

There exists a dominant theory of origin, based on a speculation that the early Kodavas had links with the ancient Greeks. Greek theatre originated because of rituals. Plays were enacted in order to worship and please the Greek gods, Dionysius being the most popular of them. Thus in the way that ritual is identified as the reason for the origin of Greek theatre, so also, Kodava theatre is said to be born out of rituals and folk, though not through worship to a particular God like the Greek icon, Dionysius. Since Kodava language, because of its minority status was not as popular as was Greek, it was not studied widely and hence the development of theatre in Kodagu has not been followed up. Rituals and folk forms can be identified as the two major roots for the origin of Kodava theatre and it would be interesting to analyze how these elements have been used in Haradas Appacha’s plays.

INFLUENCE OF TRAVELLING COMPANY THEATRES

Another note worthy aspect in the development of Kodava Theatre is that Haradas Appacha’s period coincided with the time when there was an influx of Company Theatres of Karnataka region into Kodagu. For example, the “Gubbi Nataka Company” and the “Mohammed Peer Nataka Company” were travelling in and out of Kodagu, which had influenced Haradas Appacha’s style of play writing in a major way. But it is important to note that while these company theatres mostly incorporated social and mythological themes in their productions, Haradas Appacha exclusively adapted themes from Hindu mythology to entertain and educate his Kodava audience.

In 1890, when the Tiptur Natak Company visited Madikeri, in Kodagu, Haradas Appacha had carefully observed and studied their acting style, dialogue delivery and musical accompaniments He also befriended many of the actors and even managed to land himself a few roles in these plays. With the help of a few friends, he managed to buy some of the theatrical props and costumes from one of the theatre companies that were leaving Kodagu[3]. Haradasa Apacha noted in his auto biography thus:

“I was so intrigued by the issues that were discussed in these plays and the way they were staged that I made friends with one of the men who played a powerful female character and learnt many verses from him. I also befriended many more actors who taught me many ragas. I followed the drama company day and night till the time they left Kodagu, learning and practicing the verses as much as I could.[4]”

‘…the second year again, a few companies visited Kodagu and impressed with my keen interest and enthusiasm they even let me play a few small parts in their plays. This boosted my interest in theatre, and I learnt many more ragas and verses from these companies. In about two years, I could recite hundreds of verses from my memory. This enhanced my knowledge of “ragas” that helped me significantly in composing my own poetry. The people of Kodagu started addressing me as “Kavi”…. [5]’

This seems to be the major milestone that inspired Appacha to delve deep into the theatre scene and learn the art and techniques of theatre. It led to Appacha’s maiden foray into the theatre arena through a drama Chandrahasa Kathe, composed by his friend and close associate, Sri.Venketadri Shyamaraya, a well known poet in Madikeri. He noted later:

[6]‘…….there was a huge crowd. I remember the happiness on the faces of the people and the appreciation they showered on me after watching my role, my acting skills, my voice modulation and body language; I was amazed at myself…’

In 1906, he composed Yayati Nataka, in which he infused the ideals of devotion to the king, discipline, respect for the ancestors and devotion to God. This was followed by the Savitri and Subramanya Natakas (1908) that discussed the proper conduct of women, devotion and loyalty to husband, description of man’s ideal conduct, devotion to the Lord etc. In 1909, he is said to have written a Kannada drama, Sati Sukanya/ Sukanya Parinaya, which was never published. The original manuscript was lost and till date, there is no sign of it. He formed his own drama company in 1916 and toured several places in Kodagu and to neighbouring places like Periyapattana, Hunsur etc. In 1918, he composed the Kavery Nataka depicting the importance of River Kavery, the description of the People of the region, their lifestyle, customs and traditions. In 1919, he staged “Mudduraja” another play which again was never published. This drama was hurriedly written for an impromptu performance as part of a cultural event during the departure of the then [7]Deputy Commissioner. He also learnt the Harikatha tradition (the traditional art of storytelling in India) and performed it several times to the entire satisfaction and applause of his mentors. He made it possible for his fellow beings to conceive the Kodava language as having immense poetic potential like any other mainstream language. In the same year, his name appeared prominently in the “Madras Mail” newspaper, in praise of his performance in Mangalore, with the headline, “Kodagu’s Haridas[8] in Mangalore.” It ran as follows:

‘As Shakespeare is to English, so is Haridas Appacha to us. He performed the “Shivaratri Rahasya” Harikatha very entertainingly. Even in his old age, he impressed the men and women gathered there immensely with his clever words, skilled talent and expertise in music. Thereafter, [9]Mr. Mangesharai greatly praised Haradasa’s talent. Born in Kodagu and composing literature in the Kodava language, he has proved to the world that the Kodava language has immense poetic potential. It is impossible to describe his miraculous talents in words. He is, indeed a “Haradasa”.’

CHOICE OF SUBJECTS

Locating the period of Haradas Appacha as one that witnessed turbulent changes with the British rule, especially cultural transition, it is indeed fascinating to look at the ideas that keep emerging time and again in his works. Like every society, Kodava society too underwent changes as a result of colonial rule. Haradas Appacha’s four plays give substance for careful and detailed content analyses that lend focus on the representation of modernity and the crisis of the traditional patriarchal Kodava society of his times in colonized India. He highlights gender issues, the role of women, and strongly criticizes corruption in a carnivalesque manner that brings in a Bakhtinian element of the comic. Each play he composed seems to highlight these issues in a subtle yet focused manner complete with thought provoking instances delivered in a comic fashion jolting the viewers’ minds.

One must dwell upon the choice of material that the playwright chose in order to find answers for these. Out of the vast and innumerable number of characters that enliven Hindu mythology, Appacha chose four distinct characters: Yayati, Savitri, Subramanya and Kavery. One, a king that is engaged in a classic tale of lust; the other a pativrata that defeats the God of Death in wit; another, a Son of God destined to kill the demon Tarakasura and finally, the story of a sacred river that brought prosperity to the region of Kodagu. At a glance, these plays would seem to be mere “stories” from a grand epic, retold in Appacha’s words, in Kodavattakk. So what is it that makes his rendering so unique?

V.S Khandekar in his introduction to his famous novel ‘Yayati’ says, “A writer of fiction would be guilty of transgression if he made any basic change in the character of Rama and Sita, or Krishna and Draupadi. But the same rule does not hold in respect of secondary characters; the writer of fiction may make changes in the subsidiary characters to suit his theme, even if based on mythology. It is for this reason that the Shakuntala of Kalidasa is a little different from that of Vyas, the Rambhadra of Bhavabhuti is not the Rama of the first poet[10]”. Appacha’s selection of secondary characters thereby gives him ample freedom to play around with their histories, without altering their roles in the main narrative. It is with these secondary histories that Appacha plays havoc in order to push his ideas through the medium of the myth. One over arching feature that runs through all these stories is that the characters have all been removed from the original high pedestals in mythology and have been brought down to every day, regular, quotidian set up, and, most importantly these characters have been assigned unique Kodava sensibilities that made them easy to identify with the Kodavas ethos.

Yayati for instance, the king, (who could well be a village head of the day,) did not just “happen to pass by” and chance over Devayani. Rather, in Appacha’s version, the king goes out hunting in order to save his subjects from the wild boar that had been causing havoc in the estates. Even in the indication of the passage of time of one thousand years that Puru bore the curse of the old age of Yayati, Appacha has vividly described the system of bribe and corruption that was rampant in the then Kodava society in terms of land tax, revenue, survey numbers etc. Thus Yayati comes across as any other village head/chief of the day. The feelings and emotional states he experiences are but humane.

V. S. Khandekar is of the opinion that before the year 1942-51, if he had written his version of Yayati, he would have confined himself to an elaboration of Sharmishtha’s love affair. But the novel, written in 1959 is a result of his exposure to the “strange spectacle of physical advancement and moral degeneration going hand in hand” (Khandekar 2009). It would be safe to say that in his choice of Yayati, almost half a century before Khandekar, Appacha had witnessed somewhat similar amalgamation of advancement/modernity and consequent moral degeneration facing the society. Appacha’s characterization of Yayati comes across clearly as a modern alienated man, obsessed with the blind pursuit of carnal pleasures in life. The Kodava people are likened to Yayati who would not mind the loss of spirituality and moral values as a result of blind imitation of western cultural values resulting in a degeneration of the principles of a “proper” societal set up that Appacha, like Khandekar nostalgically yearns for.

THE ROLE OF WOMEN

The idea of moral degeneration surfaces through many instances in the play where he uses the characters of Devayani and Sharmishtha to critique the modernized woman while still highlighting her power to manipulate the situation as she desires. It is interesting to note that all his plays give a lot of importance to women. The plays practically revolve around the women characters. In Savitri Nataka and Kavery Nataka, it is obvious that women play the central role. However it is interesting to note that even in Yayati Nataka and in Subramanya Nataka too, where, the plays though named after the male characters, both Yayati’s and Subramanya’s lives are largely governed by Devayani - Sharmishtha and Lavali respectively. Yayati falls prey to Devayani’s persistent obstinacy and to Sharmishtha’s lustful temptations. Both women gain their goals through their feminine charm over Yayati.

In Subramanya Nataka, too, apart from the legend of the Igguthappa Kund or the Subramanya Hillock, Lord Subramanya is shown as a forlorn lover yearning for Lavali. Once he gets hold of her, timidly proposes to elope, without her father,s knowledge . Lavali however, comes across as a strong idol of womanhood who questions traditional notions of being a “proper” woman. Thus women play substantial and decisive roles in all his plays. Both Kavery and Savitri Natakas are obviously female centric plays. In Savitri Nataka, Savitri plays the lead, tricking the God of Death into bringing her husband Satyavan back to life. Satyavan is the dutiful son who is afraid to take a wife without possessing a kingdom; his aged father is a picture of melancholy, having lost his kingdom and dignity in battle and the only other male character is the friend/ Minister, who plays the role of a Vidushaka and is ridiculed by Savitri’s female friends, again defeated in a witty wordplay. In Kavery Nataka too, the glory and power of Kavery overshadows all the male characters that bow in submission to her. Thus the role of women is pivotal in Appacha’s plays and lends momentum and character to the script, urging active discussions on stage and off-stage.

The Kavery Nataka, however, has another agenda. Apart from a ridiculing of the higher Brahmanical values and the caste system, this play highlights Appacha’s keenness on glorifying the Kodava race, as having a grand legendary lineage. However,the details he mentions in the play are not his interpretation or his version of ancestry of the Kodavas, but is as recorded in the “Kavery Purana”. His purpose of writing the play, that too in Kodavattakk, was to educate the ignorant Kodavas of a glorious “past” that they were blissfully unaware of. It is possible that Appacha fondly hoped that the knowledge of this legendary past would help boost the Kodava morale and reinstate them to a royal status. As to the question of cultural ambiguity, today, most Kodavas claim, a Kshatriya ancestry. This idea became perpetuated due to the age old proliferation of the myth of Kavery and its supposed unbreakable link with the Kodava race.

SOCIAL COMMENTARY

Another important feature that is impossible to neglect in his plays is the prominence of caste and class and an intense social commentary delivered in a satirical manner. [11]In Savitri Nataka, Appacha presents a sarcastic critique on “modernized” Brahmins and their marriage rites. But the biggest critique of course comes in the Kavery Nataka, where sage Agastya curses the Brahmins and banishes them to the level of Ammakodavas[12], stripped of their duties and rights as Brahmins. He paints a picture of lazy, opportunistic Brahmins who regard all other classes as insignificant and moreover, tricks them through their acquired hegemony of Vedic “knowledge” into fleecing their meager savings in the name of God. [13]This finds consonance in the ideas of Dr. Ambedkar who provided a subaltern perspective to see clearly the chameleon of Indian caste-ridden social set-up deceptively appearing in crimson colors and also find ways to guard the interests of the Dalits. While years later, Ambedkar strove for a casteless, class-free society, Appacha had already foreseen the problems brought about by caste discriminations and also had forewarned about the consequential social tensions.

From the works of Appacha one can glean the existent ambivalence on the idea of the “modern” in Kodava society. The confusion between being modern, progressive, reasonable and democratic and the resultant “disorder, despair and anarchy” brought about by shunning the ‘un-modern’ traditional ways is evident in his plays.

NATIONALISM AND THEATRE

One of the corollaries of nationalism was [14]sub-nationalism: a regional identity that was thought complementary to pan-Indian nationalism. The national and sub-national ideology became the substance of literary and theatrical imagination. It constructed the myth of a tradition, which, though meant to resist the colonizer, replicated the colonial image of India: a glorious past fallen on evil ways. Historical evidence suggests that Kodagu was ambivalent in its stand on nationalism. The citizens of Kodagu seem to have benefited more from the British invasion. This naturally would have made them hesitant to fight the enemy that the entire country was fighting against. With their rule, came the three most important aspects that led them to befriend their British masters.

-

They introduced an education system that later helped provide well paying jobs in the British administration for the Kodavas.

-

They introduced the cultivation of coffee, a cash crop that catapulted Kodagu to a higher status in terms of trade and economy.

-

They brought about a uniform penal code that ensured equality and a reduction in crime rates in sharp contrast to the arbitrary dispensation of justice during the days of the Haleri Rajas thus bringing about an egalitarian society.

Appacha’s life history and plays help give an understanding of the socio- political conditions of Kodagu that led to its ambivalent position in the context of nationalism, in the ‘sub-sub national’ level, penetrating a level deeper, from the national (India) and the sub-national (Karnataka). Appacha’s own exposure to national and sub national contexts helped him respond to the scenarios when they are mixed and complicated in terms of encountering the three cultures: a) His own native culture b) Mainstream Karnataka culture and c) Alien culture- The British culture in a situation of diglossia.

KODAVA THEATRE TODAY

After the period of Haradas Appacha, some of his plays were performed in and around Kodagu by students due to the painstaking efforts of stalwarts like Dr. I.M.Muthanna a great scholar and prolific writer of Kodagu. But the trend gradually changed. Theatre took a setback with hardly any plays being produced till 1976 with the establishment of the BEL Kodava Sangha, Bangalore in 1976 by B.S. Chittiappa. In the 80’s there emerged the Hosa Navya Natakas, or the new theatres that brought with it new developments in theatrical techniques which led to the construction of modern, natural dramas. This was taken up by organizations like Srishti Kodagu Ranga, Neenasam Theatre Institute etc. Here, theatre was studied rigorously as a scientific technique and paid a lot of importance to lighting, sound techniques, professional make-up techniques, the use of stage properties and stage/set construction.

But even after all this, there was found to be a severe lacunae and ambivalence in the writing and production of Kodava play scripts, centering on the then contemporary Kodava social issues and lifestyle.

‘This land is not one that is meant for Drama, Literature and Art. I burnt my fingers following that path. I am not disappointed in my efforts. I just followed the path shown to me by God almighty. But I suffer in my old age.’

-Haradas Appacha, 1940[15]

According to A.C. Cariappa, a renowned theatre personality from Kodagu, the viewers/audience has not decreased, but the doers/performers/artistes have. Thus there is a need to promote research in the area, conduct workshops and theatre festivals, bring in professional artistes and provide proper, reasonable remuneration for theatre artistes that would help promote interest in the theatre movement among the youth and save the legacy of Kodava theatre from disappearing into oblivion. It is said that the birth and death of a language depends on the literature it produces. Such is the case with Kodavattakk. With the meagre quantum of literature being produced, Kodavattakk is heading a dangerous direction.

In the wake of a dying theatre tradition and language this attempt at a critical evaluation of Haradas Appacha’s works in particular and Kodava theatrical tradition in general would be a humble contribution to the Kodava cultural scenario.

CONCLUSION

For the readers of Appacha’s works, it would come as a literary marvel as the short poems and proverbs that he uses within the play text are filled with an “excitement” that forces one to dwell on them. Each line in these poems is enthused with creativity and a style, with emphasis on rhythm, alliteration and melody that makes it hard to forget. In each of his poems he mentions the Raaga and an example from a popular song of the period. For example, [16]‘Raag : Todi; (To be sung like, ‘Haridasi Haridasi Peetambara’). The song in paranthesis is usually one that is popular and a tune that can be easily grasped even by people who aren’t well versed in the technicalities of classical music as well.

Haradas Appacha weighed every word before he penned it. Each of his plays has a philosophy for the world and a message for his audience. Yayati Nataka cautions the world against the perils of losing sight of spirituality while warning the Kodavas of the harmful consequences of their nonchalance towards tradition. Savitri Nataka epitomizes the power of the pativrata dharma that the world should take notice of and highlights the strength of prayer, devotion, and determination of the Kodava women. Subramanya Nataka upholds for the world, the might of intense love and establishes the creation of the Igguthappa hill in Kodagu. Kavery Nataka sends the message of being of immense service to the world in general and emphasizes and educates the Kodavas of their glorious past. Thus, each of his plays was a philosophical thought-capsule delivered in an entertaining style that forced one to sit up and think about life. [17]For example, in one of his plays, he commands thus:

Go, sink a well- or a pond

Feed the needy

Grant the requests for help

But only after weighing their plight

Do fast but once in eight days

And be ever devout to the ones who created you.

Indeed, his choice of Kodavattakk has rendered him the title of 'father of modern Kodava theatre' a bestowal, which during his lifetime, he was not able to savour. The father or modern Kodava theatre passed away silently into the crumbling pages of history, old, ailing and poor, in the hope for a better condition for theatre in Kodagu.

[1] M.P. Rekha, Arikattu, (Bangalore: Kikkeri Publications, 2010), 67.

Recent studies by Dr. Rekha Vasanth claims that Coravanda Appaiah, a scholar and Appacha’s contemporary had written parts of his book “Kodavara Kulacharadi Tattvojjeevini”, in 1902, a compilation of the customs and traditions of the Kodavas in Kodavattakk using the Kannada script. But Appacha Kavi can be credited with writing entire books in Kodavattakk and indeed the first person to write a play in Kodavattakk using Kannada script.

[1]Haradas Appacha, Atmacharitre, a condensed version of his autobiography, quoted in I.M.Muthanna Koḍagina Haradāsa Appacca kaviya Śrī Kāvēri nāṭaka (India:s.n, 1967), 3: “… those days it was fashionable for children from affluent families to learn the English language because it was meant to parade the wealth and opulence of those families as being powerful enough to afford the luxury of English education. And since my father had his own coffee estate to his credit, and me being his only son, he sent me to study the English education.”

[2] Titira Rekha Vasant, Kodava Rangabhoomi , (Mangalore: Prasaranga, 2001), 16.

[3] Titira Rekha Vasant, Kodava Rangabhoomi , (Mangalore: Prasaranga, 2001), 16

[4] Haradas Appacha, Atmacharitre, a condensed version of his autobiography, quoted in I.M.Muthanna Koḍagina Haradāsa Appacca kaviya Śrī Kāvēri nāṭaka (India:s.n, 1967)

[5] Ibid

[6] Haradas Appacha, Atmacharitre, a condensed version of his autobiography, quoted in I.M.Muthanna Koḍagina Haradāsa Appacca kaviya Śrī Kāvēri nāṭaka (India:s.n, 1967)

[7]Haradas Appacha, Atmacharitre, a condensed version of his autobiography, quoted in I.M.Muthanna Koḍagina Haradāsa Appacca kaviya Śrī Kāvēri nāṭaka (India:s.n, 1967)

[8] In the newspaper clipping, the name appears as Har’i’dasa and not Har’a’dasa.

[9] Ullal Mangeshrai was a great scholar and also the headmaster of the school in Mangalore in which Appacha performed the Harikatha.

[10] V.S. Khandekar, Yayati: a classic tale of lust, trans. Y.P.Kulkarni (New Delhi:Orient Paperbacks, 2009), 6-7.

[11] Haradas Appacha, Shri Savitri Nataka in Haradas Appacha Kavira Naal Nataka (The four plays of Haradas Appacha), (Madikeri: Karnataka Kodava Sahitya Academy, 1998) 16-17

[12] Nadikerianda Chinnappa, Pattole Palame:Kodava Culture- Folksongs and Traditions, trans. Boverianda Nanjamma and Chinnappa (New Delhi:Rupa & Co, 2003), xxxiv :It is believed that Amma Kodavas are the descendants of a Brahmin girl and a Kodava man. According to this belief, centuries ago, a young woman from the family of a Brahmin called Tayakat Tambiran in Malayala (Kerala) attained puberty before she could be married. So she was blindfolded and left in the forest. She happened to reach Kodagu where she met a Kodava man who befriended her and took her into his home. Their offsprings were teetotalers and vegetarians like their mother. They are called Amma Kodavas. (Names of males among them have the suffix ‘Amma’, meaning mother, implying that they follow the mother’s customs. However, since ‘Amma’ meant father in old Kannada, this could also signify that their paternal ancestor was a Kodava.) The progeny of their children, whether boys or girls, remained Amma Kodavas even if they married Kodavas. It is said that intermarriage with Kodavas increased their numbers. Although their customs were alike, Kodavas and Amma Kodavas were looked upon as distinct communities after the end of the rule of the Lingayat kings, in the early part of the nineteenth century.

[13] Dr. Ronaki Ram, Dr. Ambedkar and Nationalism, 14th April 2011, www.ambedkar.org/News/ambedkarandnationalism.html (accessed 10 May 20110)

[14] Dr. S. Chandrashekhar, Sahitya Mathu Charitre , (Bangalore:Namma Prakashana, 1999), 19-24

[15] Haradas Appacha Kavira Naal Nataka (The four plays of Haradas Appacha), (Madikeri: Karnataka Kodava Sahitya Academy, 1998) , vii

[16] Haradas Appacha, Sri Kavery Nataka in Haradas Appacha Kavira Naal Nataka (The four plays of Haradas Appacha), (Madikeri: Karnataka Kodava Sahitya Academy, 1998), 77.

[17] Addanda Cariappa, Amara Kavi Appacha, ( Virajpet: Appacha Kavi 125th Janmothsava Samiti, 1994), 49.