The ubiquitous Hanuman is in the eye of a storm because of his lineage and where he belongs, thanks to a politician’s comments. While we do not intend to contest or endorse the veracity of such statements, we explore here some of the legends and lore associated with the much-loved vanardev, or monkey god (In Pic: A late 19th-century Kangra painting depicting Hanuman paying obeisance to Lord Rama from K.C. Aryan's collection of folk art)

Hanuman is a character in the Ramayana, who was called ‘a forest dweller, deprived and a Dalit’ by Uttar Pradesh Chief Minster Yogi Adityanath during a campaign speech in November 2018. This has upset many, including members of Adityanath’s party, the BJP, with the CM having been served a legal notice. Bhim Army chief Chandrashekhar Ravan has even asked members of the Dalit community to take over Hanuman temples and appoint Dalits as priests. The controversy has piqued interest in the lineage of Hanuman—who is he and how did he come to be the simian god that so many Indians worship today?

Through this article, we explore some of the myths, legends and lore associated with Hanuman, and how he has been represented and interpreted over the centuries, in texts as well as art.

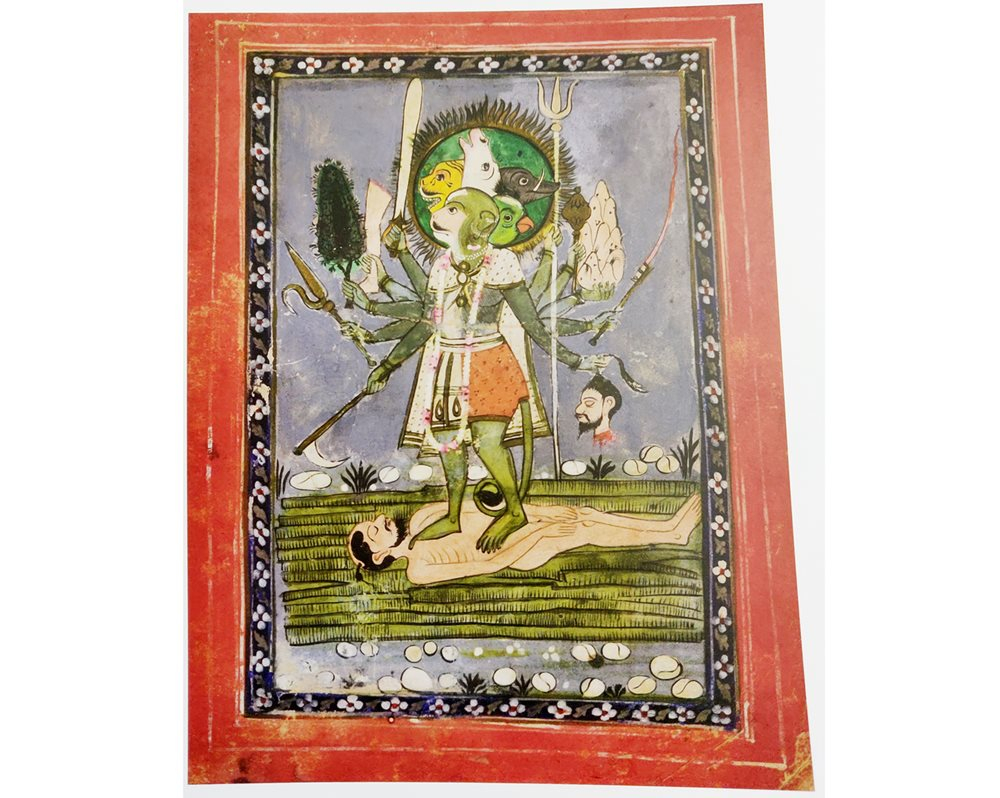

A late–19th century Panchmukhi Hanuman painting in the Pahari style from the K.C. Aryan collection. The five faces are said to represent (from viewer's left to right), Garuda, Narasimha, Hayavadana and Varaha.

Puranic Origins of Hanuman

Hanuman is most familiar to people as a character from the epic Ramayana. He is the half-monkey, half-man devotee of Rama who helps him defeat Ravana, destroy Lanka, and bring back Sita. There are many stories about the birth of Hanuman in Puranic literature. In the Karhba Ramayana Purva Kanda, it is said that Shiva and Parvati were playing in the forest as monkeys and Parvati got pregnant. Unwilling to give birth to a monkey child, Shiva entrusted the embryo to Vayu, who deposited it into the womb of Anjana, the monkey woman. Hanuman is then born to Anjana and her husband Kesari.

One of the stories in Vettam Mani’s Puranic Encyclopedia is of Shiva entering the body of Kesari, Anjana’s husband, ‘in his fierce and effulgent form (aspect)…and ...[having] coitus with her. After that Vayu (Wind-god) also had coitus with her. Thus as a result of the sexual act by both the Devas, Anjana got pregnant. Later, Anjana was about to throw into the valley of the mountain her new-born child as it was an ugly one when Vayu intervened and saved the child. Hanuman was the child thus born of Shiva and Vayu’ (Bhavisya Purana, Pratisarga Parva).

The late K.C. Aryan, well-known artist and art collector and founder of Gurugram’s Museum of Folk and Tribal Art, had studied the Hanuman legend extensively. In his seminal book, Hanuman in Art and Mythology (1975), which he co-authored with his daughter, art historian Dr Subhasini Aryan, he talks about the birth and life of Hanuman in the Shiva Mahapurana, the Skanda Purana, the Mahabhagvata, the Brihad-dharma, the Bhavishya Purana, and the Mahanataka, which refer to Hanuman as an ‘amsha of Shiva as well as a rudravatara‘.

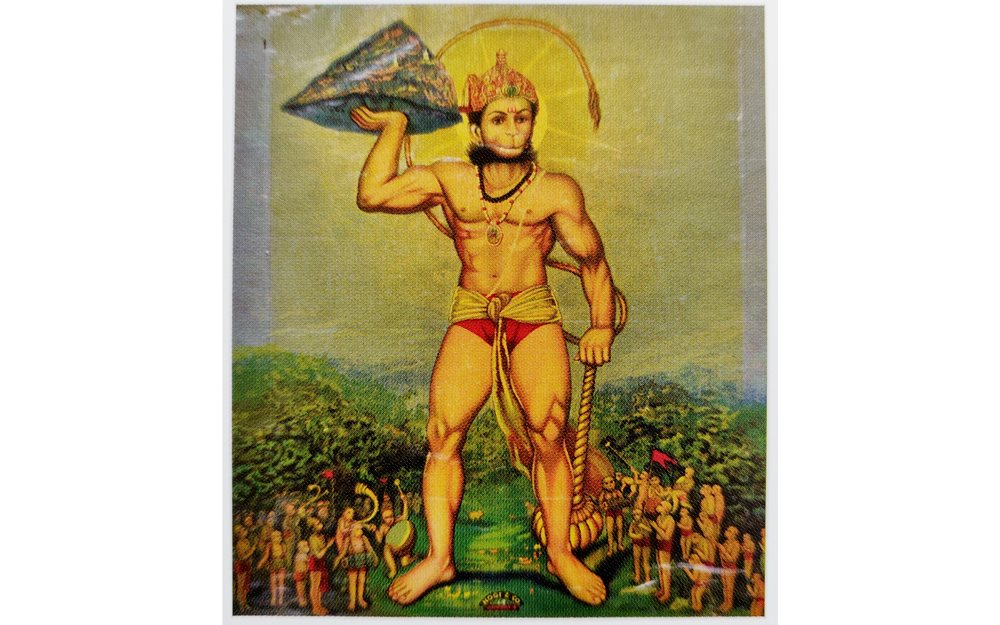

A Raja Ravi Varma Press olegraph (20th century) of Hanuman holding the Sanjeevani mountain in one hand and a mace in the other from the K.C. Aryan Collection

Hanuman and the Tribes of India

Further, Aryan writes, ‘Apparently, the tribals of Bihar mention the Anjana village in Gumla-Pramandal, Ranchi district, as being the place of his birth. Countless legends connected with various episodes from his life are woven around the old temples scattered all over this region. The natives of Karnataka believe that their land has the honour of being his birthplace. The ruins of Pampa and Kishkindha, places mentioned in the Ramayana, still exist around Hampi in Ballari district.

‘It is also believed by some people in Central India that like the other vanaras mentioned in the Ramayana, Hanuman was also a descendant of the vanara clan or tribe that inhabited this part of the country since primitive times. By and large, most scholars regard Nasik as the God’s birthplace. Sociologists have tried to prove that Hanuman was an aboriginal god worshipped in the pre-Vedic period. Other scholars opine that he was a folk god and the credit for the importance and popularity enjoyed by him goes to Valmiki. Yet another view advanced by Father Camille Bulcke is that the worship of Hanuman coalesced with that of the yakshas venerated in ancient times for being valiant (vira) and on account of their association with fertility cults. V.S. Agarwal has drawn numerous analogies between the two‘ (Hanuman in Art and Mythology, Aryan and Aryan).

A 20th-century painted wooden door of Panchmukhi Hanuman from Rajasthan, from the K.C. Aryan Collection

Hanuman, the Forest-dweller

According to Dr Subhasini Aryan, Hanuman ‘belonged to the vanar tribe, or van + nar, which means a forest dweller…’ even if he has been referred to as kapi (monkey) and bandar in Tulsidas’ Ramcharitmanas (in Sundar Kand). Dr Aryan and her brother B.N. Aryan have curated an art exhibition running through December 23, 2018 at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts in Delhi. Called ‘Hanuman: The Divine Simian’, it displays around 300 works collected by K.C. Aryan. However, B.N. Aryan has not delved into the lineage, folklore and myths associated with Hanuman in the exhibition, which is primarily a visual representation of the simian god in folk arts ranging from Rajasthan and Bihar to Kashmir and Nepal, and figurines from as far back as the sixth and seventh centuries CE.

Over a telephonic conversation, Dr Aryan is euhemerist in her interpretation of the legend of Hanuman, but she is not the first scholar to connect mythology with history. In his book Hanuman’s Tale: Messages of a Divine Monkey, Prof. Philip Lutgendorf refers to treatises like C.N. Mehta’s Sundarakandam or The Flight of Hanuman [The Vanara (Superman) Chief] By Air (1941), ‘which argue that the events and places of the Valmiki Ramayan were not “mere figments of the poet’s imagination” but “based on facts” (preface).’ Arguing against such an approach, Dr Kesavan Veluthat (retired professor of history, Delhi University), says, ‘The Ramayana is not a historical document, it’s a kavya and should be treated as such.‘ He is unwilling to comment on any public statement, saying, ‘Myth can’t be falsified or verified, history can be’.

A 19th century Kangra painting of Panchmukhi Hanuman standing over Ahiravana after slaying him, from K.C. Aryan's Collection

Dr Arshia Sattar, who has done extensive work on the Ramayana and Hanuman, also doesn’t ‘look for historical roots for mythological characters’, but explains over an e-mail that she ‘can see that history can show us how they were appropriated by various groups and perhaps even the reason for that appropriation.’ And Hanuman can be seen to speak for lower castes in some modern literary interpretations: Lutgendorf (2007) cites Bhagvatisharan Mishra’s 1987 book Pavanputra: Atmakathatmak Shreshtha Upanyas ('A Unique Autobiographical Novel'), which describes how ‘during Rama’s long encampment in the rainy season, Hanuman debates the merits of caste hierarchy (varnasrama dharma) with his master, pointing out the excesses to which it will lead in the kali yuga.’

Interestingly, in the Hanuman Chalisa (a prayer in praise of Hanuman), there is a line that calls Hanuman janeyu sajai (one wearing the sacred thread), like the Brahmins. While some have interpreted this to symbolise that Hanuman was a Brahmin or twice born, others think of this as conflicting with their notion of Hanuman. However, Dr Sattar says such conflicts are perfectly acceptable in the case of oral traditions. ‘The traditions that consider Hanuman a tribal god,‘ she writes, ‘are obviously not the same as those that give him a janeyu. That's how Hinduism works. Even though we know that Hanuman is Vayu’s son (Pavanasuta, Maruti, etc.), he is also called Shankara Suvan because the Shiva Purana has a story about him being born of Shiva's sperm. We hold both these ideas of Hanuman in our heads at the same time.’

Prof. Lutgendorf’s book does refer to the many ‘historical‘ identities ascribed to Hanuman—as a tribal, a Dalit, a Neanderthal, etc. He also touches on the potential class/caste overtones to the dichotomy of Hanuman’s iconography as a ‘virile‘ (warrior) and ‘servile‘ (bhakti) god as well—‘the virile and assertive warrior appealing more to lower-class and rural people, and the tearful, self-denying devotee more to middle and upper castes and to urbanites—though this generalization admits of myriad exceptions.’

The fascinating folk background of Hanuman stories notwithstanding, the loveable simian god seems to have become politicised. Discussing how Hanuman figures in the ideology and practice of Hindutva, Lutgendorf (2007) observes that he ‘seems to have been considered good for “little people”: children, tribals, the Dalits, or the unruly urban youth.’

(All photographs have been published with permission from B.N. Aryan from his father's collection)

More on Ramayana on Sahapedia

K. Satchidanandan on Alternative Ramayana Narratives