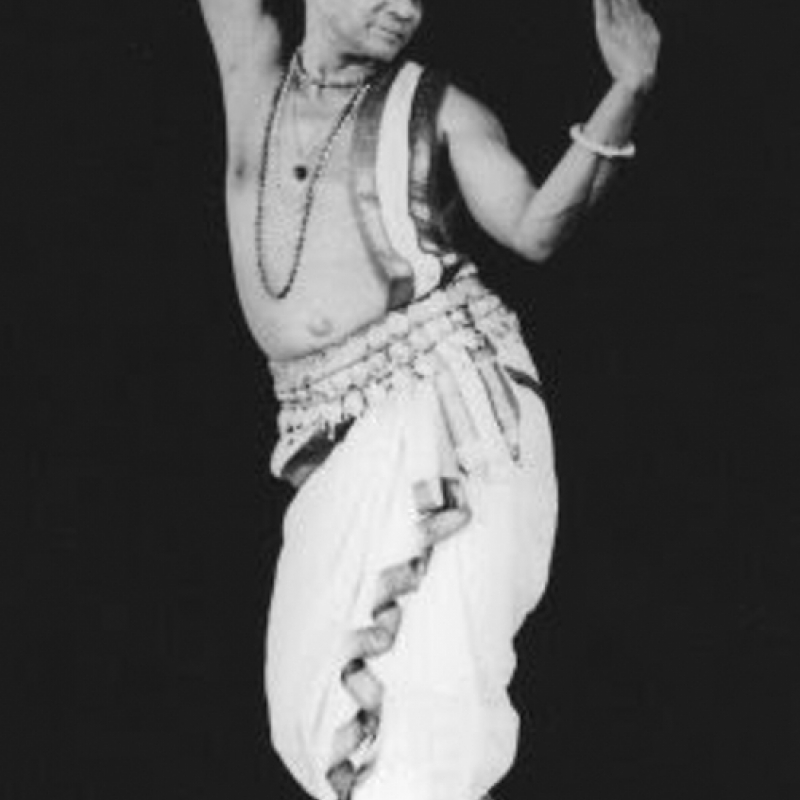

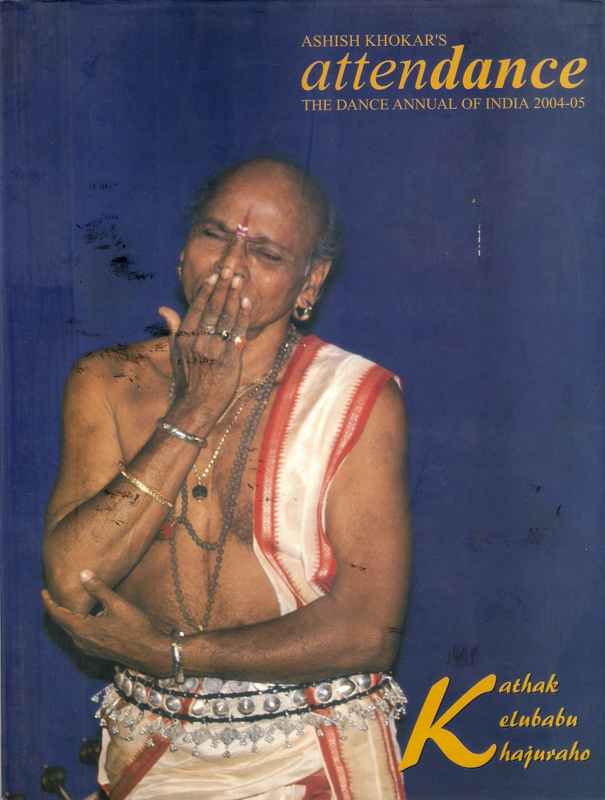

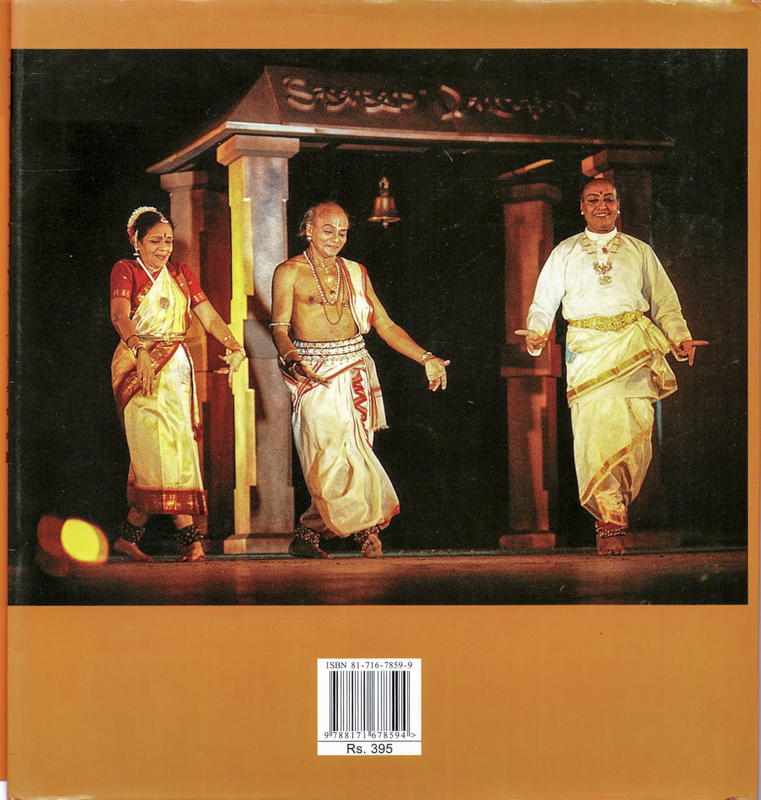

Out of the four pioneering gurus of Odissi dance (fountainhead Pankaj Charan Das, Deba Prasad Das, Mayadhar Raut), it is Kelubabu, as he was universally known, who brought the dance form into the limelight. That is because not only was he a prolific dancer, composer, choreographer, and promoter of the art of Odisha, hailing as he did from the professional stage and from the famed Kali Charan’s Orissa Theatres and later Annapurna B and still later the KVC (Kala Vikash Kendra), but also his scores of star students ensured his legacy multiplied and travelled further. These star students, beginning with Sanjoo Naani or Sanjukta Panigrahi, Kumkum Mohanty, Sonal Mansingh, Rani Karnaa, Aloka Kanungo, Alarmel Valli, Malavika Sarukkai, Madhavi Mudgal and Protima Bedi, were among the well-known ones. Many others learnt from these star students, thus the dance form itself and Kelubabu’s style mutated and multiplied manifold. His name is written now in gold letters and his son Ratikant Mohapatra and outfit, Srjan, now ensure that both his memory and style are validated and furthered. Guru Kelubabu’s partner in dance and life, Guruma Laxmipriya, still provides guidance to all efforts made by Ratibabu.

Kelubabu was born on January 8, 1926, in Raghurajpur, near Puri. His father, who curiously carried the same name as Pankaj Charan Das’s mother—Chintamani, came of a long line of patachitrakars, or painters of religious scrolls. He had an abiding interest in song and dance, but only in its religious aspects. He used to play the drum and dance ecstatically at temple festivals, and the young Kelu watched him entranced. In his village near Puri, there was a jatra[1] party as well as two gotipua[2] dals, one led by Mohan Maharana, the other by Balabhadra Sahu. As a child, Kelubabu was constantly exposed to performances by these teams. He went to school, but with so much music and dance around him and within his reach, he could hardly concentrate on studies. Instead of playing with his schoolmates, Kelubabu spent every evening at Balabhadra Sahu’s dal, watching the gotipuas practice, and secretly longing to be one of them. Seeing his intense interest and realising the boy’s potential, Balabhadra Sahu asked him one day if he would like to dance. In tears, the boy mumbled ‘yes’. His mother agreed to his request, but the secret was kept from his father, who thought that gotipuas were vulgar and danced only for money. He was not against singing and dancing per se, for he had put his two older sons in Mohan Sundar Devagoswami’s leading Ras Leela[3] party, but he had no patience with the gotipuas and their cult. Kelucharan did not join the ranks of gotipuas, but received all the training they did. This went on for three years. Now came Devi Puja, an important religious festival, and Balabhadra Sahu believed this was the right occasion for Kelucharan’s debut as his pupil. The boy’s mother was willing, but the father had to be told. When he was asked, and learnt of all that had been going on for a long time behind his back, he was furious. He would allow his boy on the stage, but never with the gotipua gang. He instantly recalled his two older sons from Mohan Sundar Devagoswami’s Ras party—they were now old enough to look after the family’s affairs—and Kelucharan took their place.

From the first moment of his entry, he was a hit. He was given all the prize roles—the child Krishna, Radha, her sakhi Lalita. He spent twelve years here and when he grew up, he played the role of the mature Krishna. But even more than dancing, what he gained here was the opportunity to play the drum—the pakhawaj—and the tabla, not as part of his work but on his own initiative, and because of his profound interest in the art. He stayed with Devagoswami as a member of his family; the only payment he received was what was given, arbitrarily, to his father when he came to Devagoswami to claim it. When there were no performances, Kelucharan used to occasionally return to his village. On one such visit, about five years after he had joined Devagoswami’s group, Kelucharan’s father saw the boy, now 14 years old, going out clutching something. Suspicious, he demanded to see what it was, and when he found that the boy had a pack of playing cards, he concluded that he must be gambling. He flew at Kelucharan, abused him and forbade him to go out of the house. Deeply hurt, Kelucharan slipped away from the house the same evening, never to return as long as his father lived.

Kelucharan spent his entire boyhood and early youth in the Ras Leela party, staying with Devagoswami, and serving him like a son. Later, Devagoswami contracted leprosy, and Kelucharan, more than anyone else, looked after him. Those were War years and the performances were occasional. A film, Kangan, was running at a local cinema house and everyone raved about it. Devagoswami did not approve of anyone watching films, but Kelucharan was tempted to take the risk. He disappeared one night, and on his return, at about 1 o’clock, was confronted by Devagoswami. When the Guru learnt where the boy had been, he raged and stormed. Kelucharan felt he had done no wrong and did not deserve this humiliation. Next morning, he prostrated himself at his Guru’s feet and left. It was the last the two saw of each other.

Back in his village, Kelucharan found little to do. He had not learnt the art of his forefathers, painting, nor studied. All he could do was sing, dance and play a variety of drums. He was too old to become a gotipua and had lost interest in the jatra, for he found it rather too amateurish. The village had nothing else to offer him. He was reduced to serving a betel-leaf cultivator. He had to fill countless pots of water and carry them a distance to feed the plants, to pluck the leaves and make them into bundles, for sale. He earned about five annas a day, and this continued for a year. Still he did not lose interest in music and dance, but spent the evenings at Balabadhra Sahu’s akhada, watching the gotipuas and engaging in discussions with the guru.

One day he heard that an ashtaprahari was due to be organised in Cuttack by a big zamindar. This involved the 24-hour chanting of the god’s name for a period of a month and a day. Kelucharan decided to participate as a drummer. Every day he played the pakhawaj, tabla or khol for hours without a break. He made a great impression and was handsomely rewarded at the end of the ashtaprahari. He was taken to meet Kali Charan Patnaik, then engaged in running Orissa Theatres. Kelucharan immediately received an appointment as a drummer. The dance director, who was also a master percussionist, was Durlabh Chandra Singh. There was also Harihar Raut, who was an expert drummer, but in addition assisted in music and acting. Kelucharan benefited a great deal in his knowledge of rhythm and its complexities from his association with these two older men. But what he missed most was dancing, and this grieved him. At this time, Harihar Raut’s younger brother, Mayadhar Raut, joined Orissa Theatres as a child artiste. One night, during a performance, Kelucharan sprang a high fever and could not play the drum till the end. Kali Charan thought he was shamming and reprimanded him. As always, Kelucharan could not bear to be humiliated and promptly left Orissa Theatres. He returned to his village, and now joined a new Ras Leela party that had been started there by a zamindar, Budhanath Raut. He was appointed director, and took major roles in plays. The Ras party lasted hardly eight months, after which Kelucharan was again without work. Precisely at this time the Annapurna B Group was formed in Cuttack, and Kelucharan easily found a foothold there.

Kelubabu was earmarked by destiny to play a big role in the establishment of Odissi as a dance form. His life story is the story of Odissi as the form grew and developed and his life’s journey represents the milestones of the form. Kelubabu married his dance partner Laxmipriya and they had two children, daughter Chinamayee (Das) and son Ratikant, who is the inheritor of his parents’ legacy. Ratibabu continues his work and mission with the support of many. Kelubabu’s students are a legion: Sanjukta Panigrahi, Kumkum, Protima Bedi, Madhavi Mudgal, Aloka Kanungo, etc.

His demise on April 7, 2004, was mourned nationally.

Endnotes

[1] Jatra is a traditional itinerant theatre of eastern belt of India, which delivers social and political messages for the masses through theatrical performance.

[2] Gotipua is a dance form said to be the precursor of the Odissi classical dance, performed mainly by young pre-pubertal boys dressed as girls, in an era when girls could not readily dance in public, who are trained in akhadas.

[3] Ras Leela is a form of devotional dance centered around the Krishna cult involving his beloved Radha or sakhis/gopis of Radha. It is prevalent and popular in belts where Krishna lore is predominant.