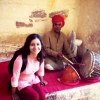

The 400-year-old oral tradition of storytelling, Kaavad baanchana, is struggling to stay alive in Rajasthan. However, there have been some attempts at preserving this unique art and the craft of kaavad-making in the modern era. We explore how craftsmen and artistes are trying to keep kaavads vibrant. (Photo courtesy: Saad Akhtar/Flickr)

We know of the Greek’s Pandora’s Box and of the Bag of Mysteries from Yoruba mythology. In India, too, we have several containers that hold our imaginations, from the ‘bowl of nectar’ from the Samudra Manthan to goddess Lakshmi’s ever-flowing pot of wealth. But the most tangible of all we have among Rajasthan’s many wonderful crafts—a box of infinite stories. Known as kaavad—or ‘chalta-firta mandir’/travelling shrine[1]—this intricate wooden box has traditionally held countless stories to enthral audiences, unravelled only by the specialised bhaats. Unfortunately, though, as is the case with many of the country’s indigenous arts, the ecosystem around the kaavad is in a crisis in modern times.

While Rajasthan has an incredibly long list of historic monuments and sites,[2] its glory is not confined to the heritage that charts its geographical space. Its long-standing cultural traditions inspired certain art works that became specific to the region—kaavad is one such example.

A Lesser-known Form of Storytelling

This unique craft of storytelling comes from Rajasthan's Marwar district. However, this is not to be confused with the homophone the Kaavad/Kanwar yatra, which is an annual pilgrimage made by Shiva devotees in the Hindu month of Shravan.[3] Made of handcrafted wood, the kaavad’s structure is akin to a colourful ‘cupboard’.[4] Its uniqueness lies in its execution with a closed panel (bund paat, on the left), an opened panel (khul paat, on the right) and a secret panel (gupt paat, behind the sliding panels),[5] skilfully made by the suthars (carpenters) of the Mewar district. Painted with vibrant colours, its complex emblems are used by the kaavadiya bhaats (storytellers) to recite the many tales from within the same kaavad box to an enthralled audience.[6]

Also read | Ragamala Paintings: Marrying Music and Art

The suthars are skilled in building and painting the box with such complexity that the bhaats can variate the story for the jajmans (hereditary patrons) and audiences, incorporating elements of their lives and families into the narrative—making them relatable and sought-after. In that, it allows each image to be religious, mythological, genealogical, eulogical, social, contemporary or anything, thus, making the kaavad ‘highly inclusive’.[7]

Thus, the suthars and kaavadiya bhaats together invoke spirituality and awareness among their patrons with their craft and storytelling, respectively.

Ritual to Recreation

Over time, though, the age-old tradition of kaavad-making and kaavad baanchana have changed.

That it survived and adapted to demands of the hour was gathered in a conversation with Satyanarayan Suthar, a traditional national-award-winning kaavad-maker from Rajasthan’s Bassi village, Chittorgarh.[8] Suthars are now customising kaavads (currently available in different colours and sizes, narrating only a single story) as collectors’ items rather than the original shrines. The new ‘altered kaavads’ thinly obscured the 12-inch traditional red kaavads, also called the ‘Madwadi kaavads’, which held the potential to narrate several stories within its limited imagery.

Unfolding Pages

One of the innovations, keeping its essence intact, is the illustrated children’s book Home (published by Tulika).[9] Home is a standing book, which can be accessed from both sides leading to a central panel (like the secret chamber of the kaavad) with a window[10]—mirroring the way one narrates a kaavad. The book cover is lush with illustrative figures which propels storytelling, giving children a chance to weave their own story,[11] each time different, as in case of the traditional kaavadiya bhaats.

From Homes to Exhibition Spaces

While earlier bhaats would go from house to house narrating their stories, now with both the art and the craft nearing disappearance, the communities of suthars and kaavadiya bhaats are struggling to make a livelihood. Kojaram Bhaat from Ramdevra village in Jaisalmer has been preserving his ancestral profession of kaavad baanchana for around 40 years, but from constantly travelling between Diwali and Holi narrating stories across villages, now he only receives a few requests for short two-hour mechanical narrations. Previously, a single panel would deserve a free-flowing narration of one-and-a-half hours. For sustenance, Kojaram and his fellow bhaats have taken to working as farmers, construction workers, etc.

Also read | Learning from Abundance: Many Mahabharatas of Rajasthan and What They Can Tell Us

However, there are a few ongoing projects that are attempting to save fragments of this craft in either the exhibition space or as performances. Thespian Akshay Gandhi’s Kaavad Project is one such example, wherein he has brought kaavad baanchana on to the stage. The project’s site explains: ‘Kaavad Katha – Maya’ is a collaboration between theatre artistes, visual artists and illustrators, musicians, a movement artiste and a mask maker, bringing Rajasthan’s lost form of Kaavad katha to the proscenium stage with life-size paintings, live and original music, original stories in poetry and a solo performer.

In addition, suthars of Bassi village have attempted to retain the (original) structure of the kaavad as miniaturised souvenirs, toys and decorative pieces for tourists and children.[12] Satyanarayan Suthar has held several exhibitions and has sold his work online, both in India and abroad. His kaavads range from six inches to 12 feet.

So, ‘does innovation (necessarily) mean extinction?’[13] Yes and no. That this 400-year-old tradition of storytelling is on its swan song is no secret, but by figuring out different ways to keep the narrative alive, some elements of this unique craft will at least be around for future generations to see and experience. But then, that’s still open to debate.

This content has been created as part of a project partnered with Royal Rajasthan Foundation, the social impact arm of Rajasthan Royals, to document the cultural heritage of the state of Rajasthan.

A version of this article was also published on South Asia Monitor.

Notes

[1] Nina Sabnani, "Prompting Narratives: The Kaavad Tradition," India International Centre Quarterly 39, no. 2 (2012): 13. Accessed July 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/41804036.

[2] Mahendra Sethi and Mohit Dhingra, "A Critical Appraisal of Concepts and Methods in Cultural Revival and Place Making in Cities," Indian Anthropologist 48, no. 2 (2018): 27. Accessed July 6, 2020. doi:10.2307/26757763.

[3] The latter is an annual pilgrimage taken up the devotees of Shiva in the month of shravana.

[4] "The Story of the Kaavad," Ishan Khosla Design, Oct 2012. Assessed on July 5, 2020. https://ishankhosla.com/work/story-kaavad-devotion-decoration

[5] Sabnani, "Prompting Narratives," 13. Accessed July 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/41804036.

[6] Sabnani, "Prompting Narratives," 11. Accessed July 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/41804036.

[7] Sabnani, "Prompting Narratives," 12. Accessed July 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/41804036.

[8] Shared during a telephonic conversation.

[9] Sabnani, "Prompting Narratives," 13–14. Accessed July 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/41804036.

[10] Sabnani, "Prompting Narratives," 15. Accessed July 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/41804036.

[11] Sabnani, "Prompting Narratives," 15–16. Accessed July 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/41804036.

[12] "The Story of the Kaavad". Ishan Khosla Design, Oct 2012. Assessed on July 5, 2020. https://ishankhosla.com/work/story-kaavad-devotion-decoration

Biblography

Aashima. "Nina Retells the Story of Indigenous Art". The Life of Science.com, Dec 2016. Accessed on July 4, 2020. https://thelifeofscience.com/2016/12/06/2407/

Hooja, Rima. "Icons, Artefacts and Interpretations of the Past: Early Hinduism in Rajasthan." World Archaeology 36, no. 3 (2004): 360–77. Accessed July 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/4128337.

Topsfield, Andrew. "Court Painting at Udaipur: Art under the Patronage of the Maharanas of Mewar." Artibus Asiae Supplementum 44 (2002): 3–327. Accessed July 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/1522717.