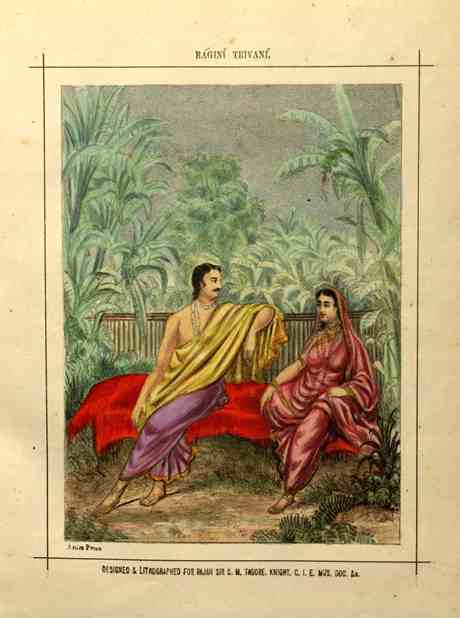

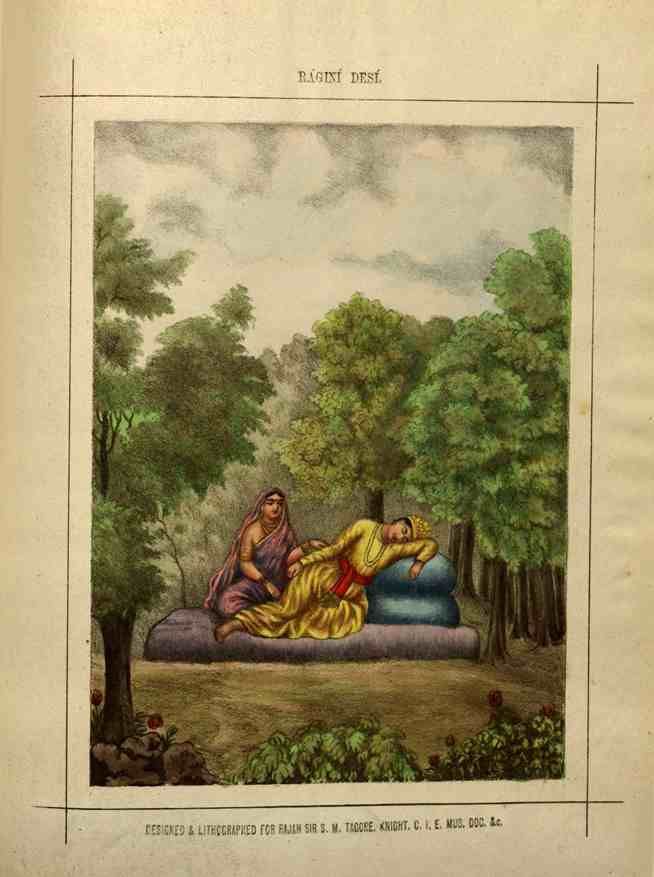

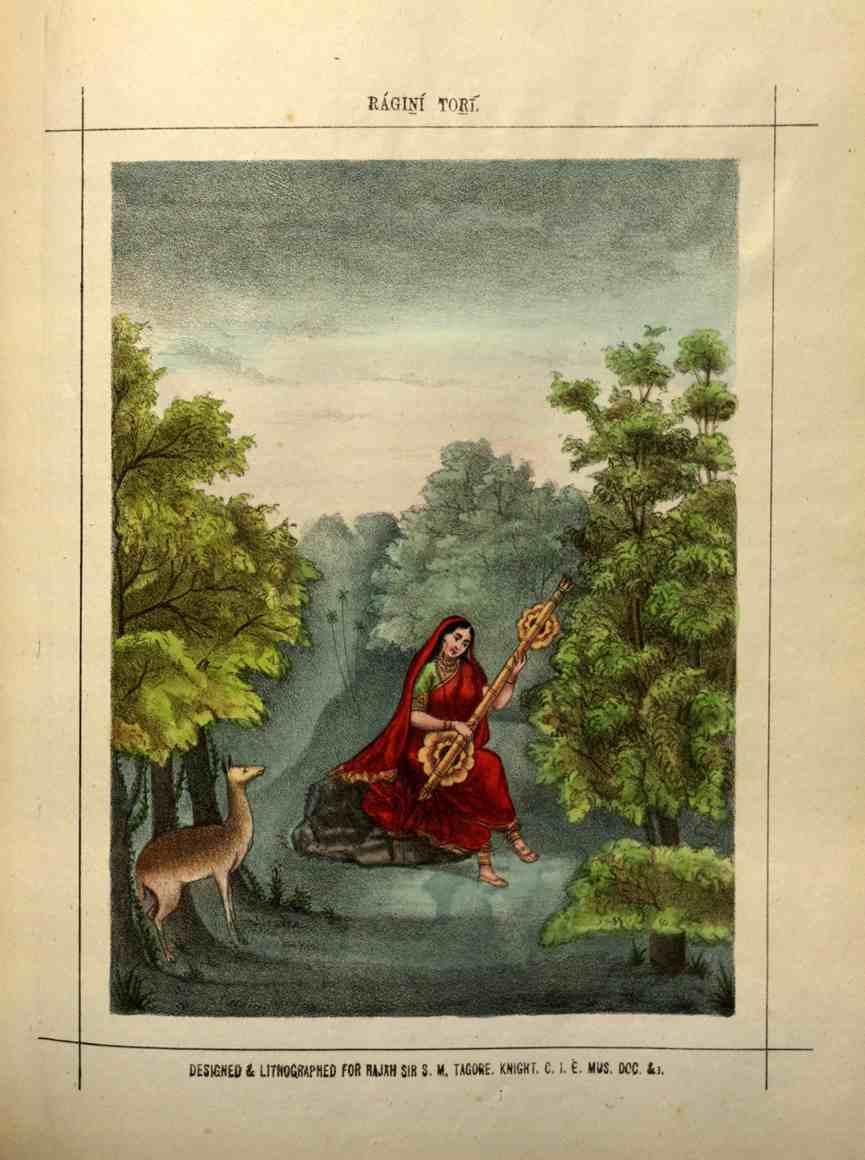

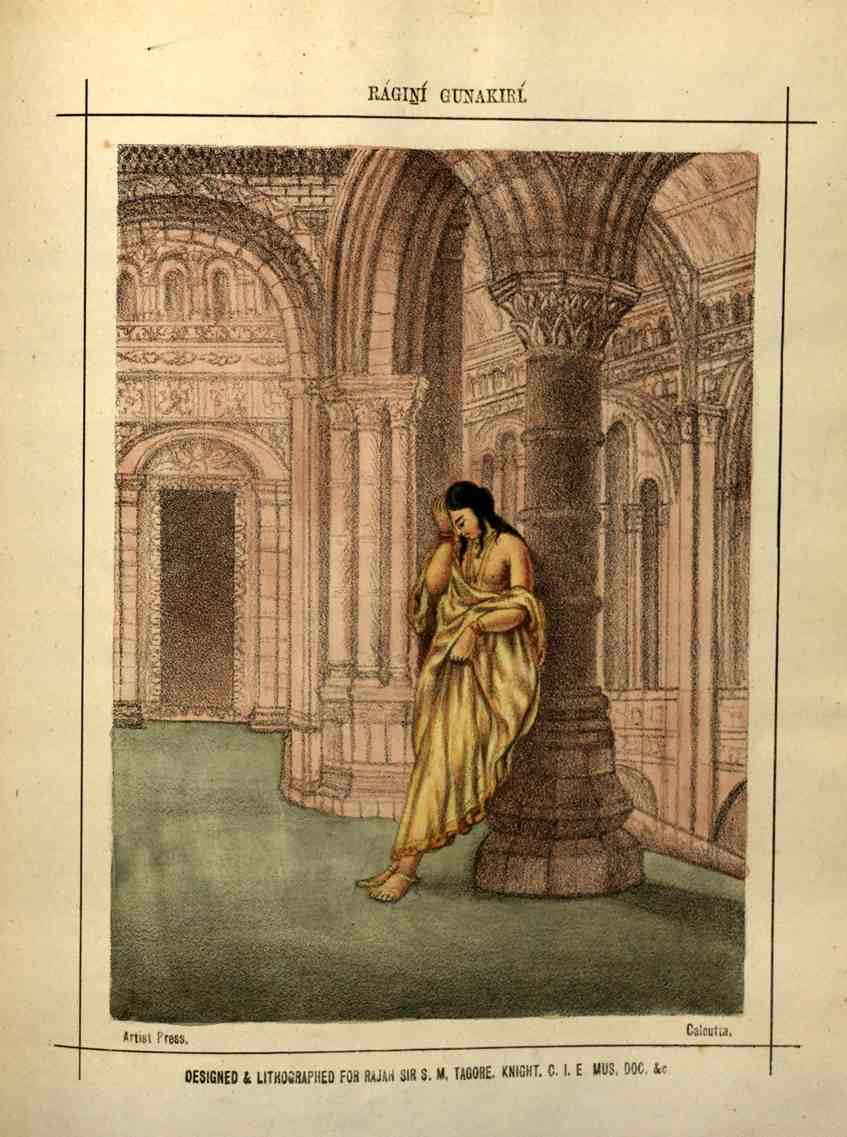

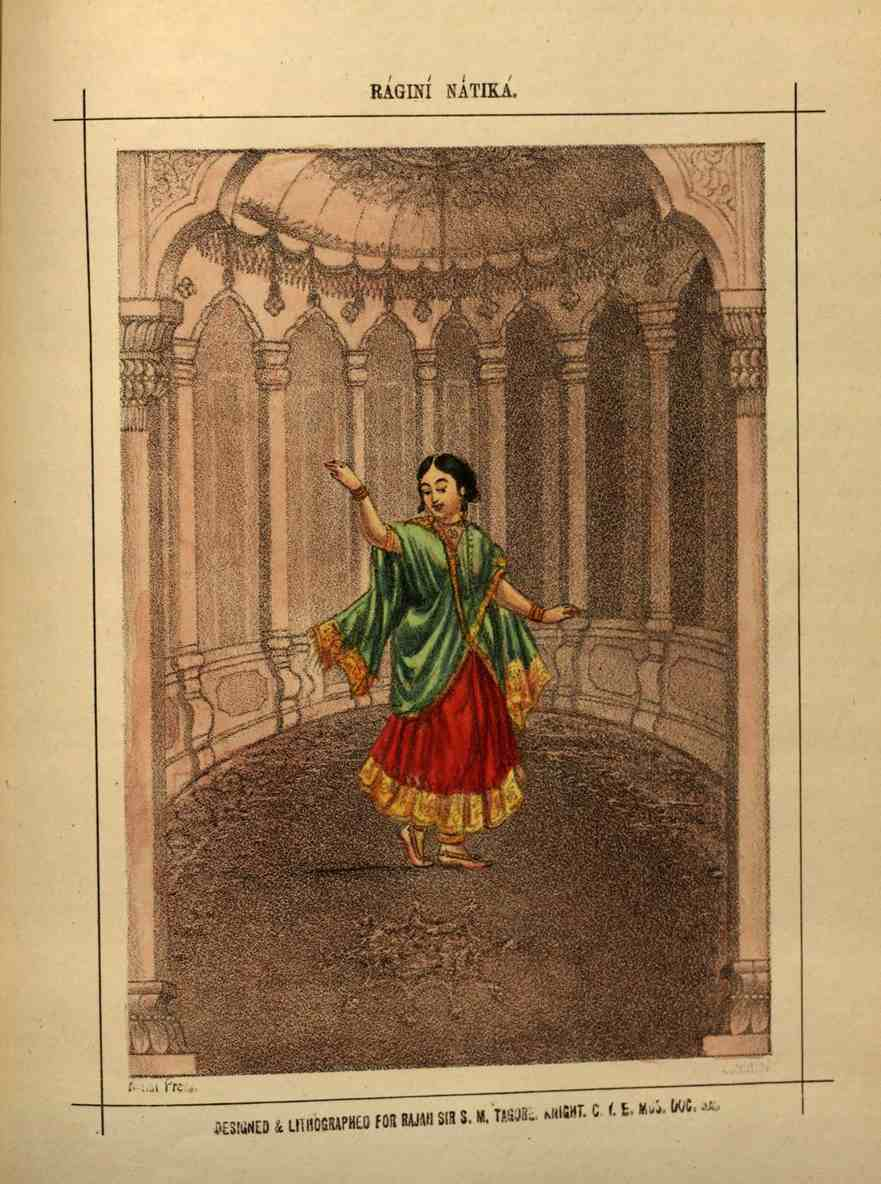

A Ragamala—meaning a ‘garland of ragas’ in Sanskrit—is a set of miniature paintings depicting the ragas, a range of musical modes arranged in specific sequences. We look at this genre of painting which captivated artists and patrons for over 400 years. (Photo courtesy: Six Principal Ragas, With a Brief View of Hindu Music)

Attempts to synthesise the visual and musical worlds of the arts have a longstanding history. Goethe, Walter Pater and Wassily Kandinsky are famous Western scholars who held up the idea that the union of music with art can be seen everywhere. Goethe even said that architecture was but ‘frozen music’. This school of thought has long existed in the Indian subcontinent as well. It dominated an entire genre of Indian miniature paintings for nearly 400 years, making them one of the most popular brackets of miniature paintings in the region.

Related | Sourindro Mohun Tagore

A Ragamala—meaning a ‘garland of ragas’ in Sanskrit—is a set of miniature paintings depicting the ragas, a range of musical modes arranged in specific sequences. The root word ‘raga’ means colour, mood and delight. [1] Each painting, therefore, represents a specific mood—often love—in its different facets and devotion. They are occasionally accompanied by a brief poetic inscription to aid this communication. [2]

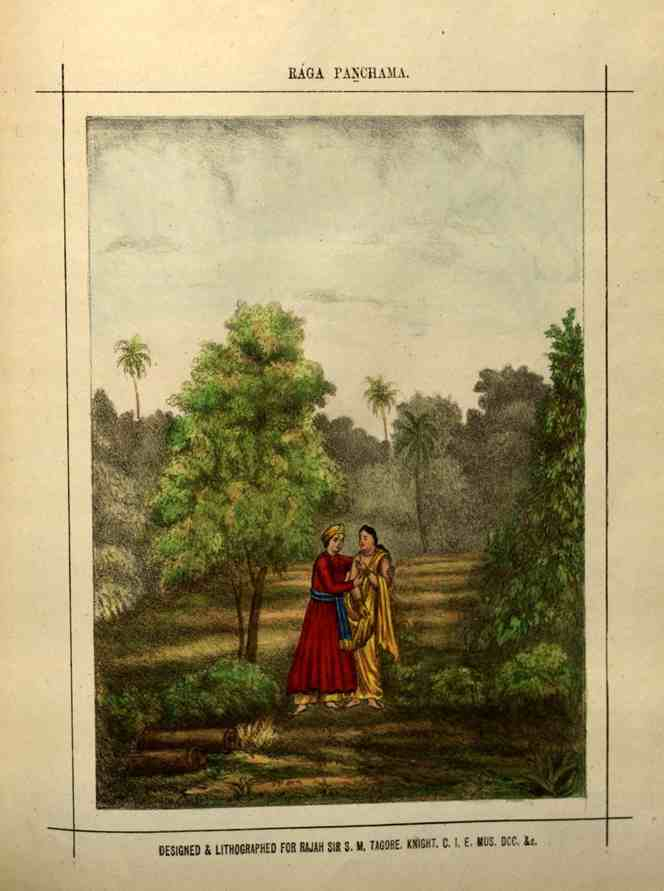

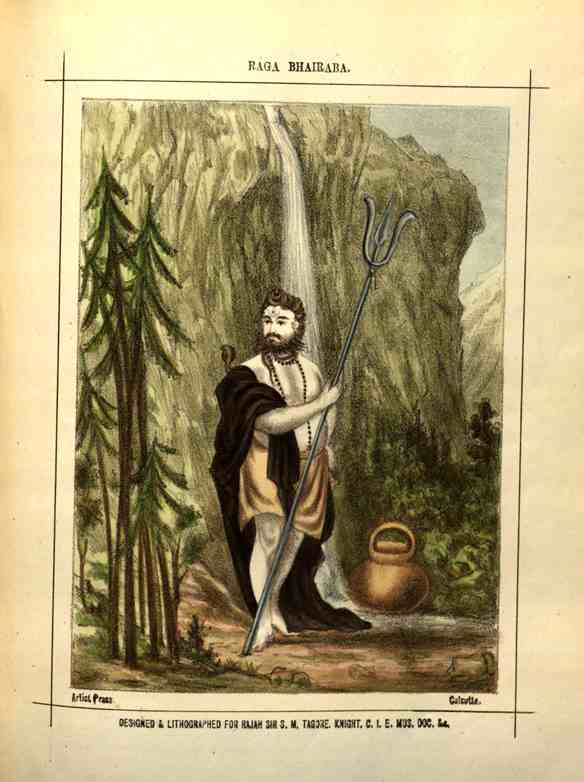

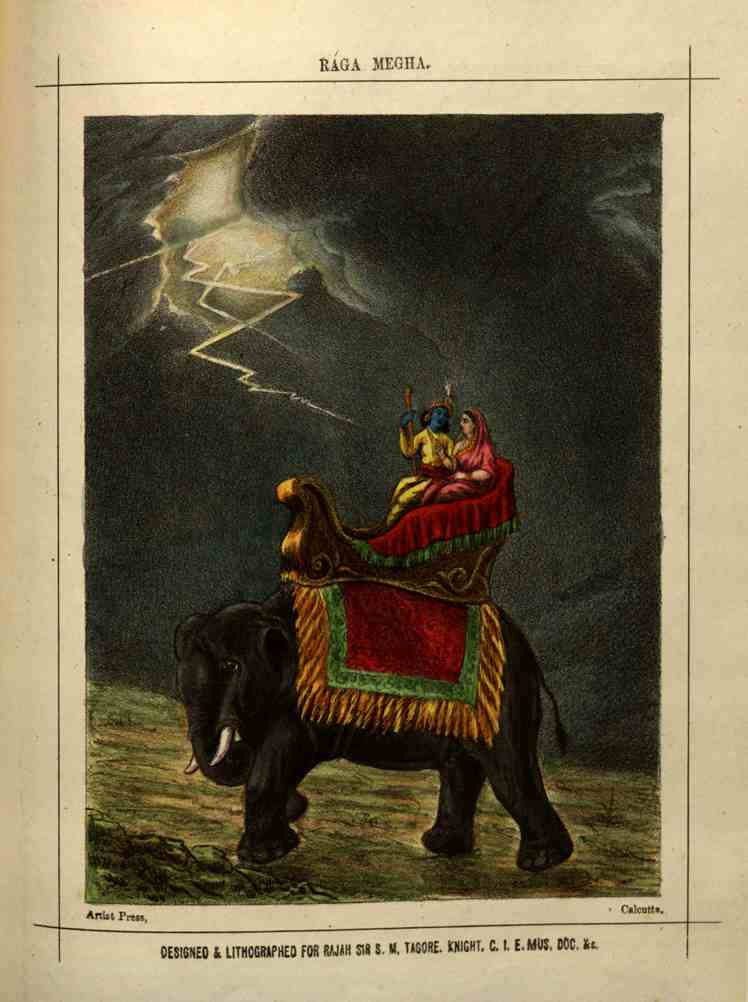

While Ragamalas were first identified as a distinct genre of painting only in the second half of the fifteenth century, their ancestry can be traced back to the first mention of the ‘raga’ in the fifth–eighth-century Brihaddeshi treatise on music, [3] which says: ‘A raga is called by the learned that kind of composition which is adorned with musical notes . . . which have the effect of colouring the hearts of men.’ [4] There are six main ragas—Raga Sri, Raga Vasanta, Raga Bhairava, Raga Panchama, Raga Megha and Raga Natta Narayana—each associated with specific themes on which musicians, painters and poets create variations. Organised as a family, each principal raga then has derivatives/relatives called raginis (imagined as the raga’s consort or wife), ragaputras (sons) and ragaputris (daughters). A Ragamala, therefore, is a series of miniature paintings depicting the moods and variations of not only the main ragas but the derivatives as well. They’re usually a set of 36, but this can go up to 110 parts too. [5] The earliest known Ragamala painting has been found on the margins of a now missing manuscript, dated c. 1475, from western India. [6]

Iconography and Symbolism

Starting from the sixteenth–seventeenth centuries, Ragamala paintings used images of Hindu deities to personify the musical notes in the raga. In that vein, Raga Bhairava became Lord Shiva, with his vaahana (vehicle) Nandi. [7] Raga Megha was pictured as Lord Vishnu wearing a garland of flowers, with a peacock sitting at his feet. [8] The ragas, moreover, are also associated with the six seasons—summer, monsoon, autumn, early winter, winter and spring; and different times of the day—dawn, dusk, night, and so on. [9] Thus, it is no surprise that the music of the ragas/raginis—and their paintings—inspire a connection to a time of day, year, mood or god.

Also see | Ragas and Raginis

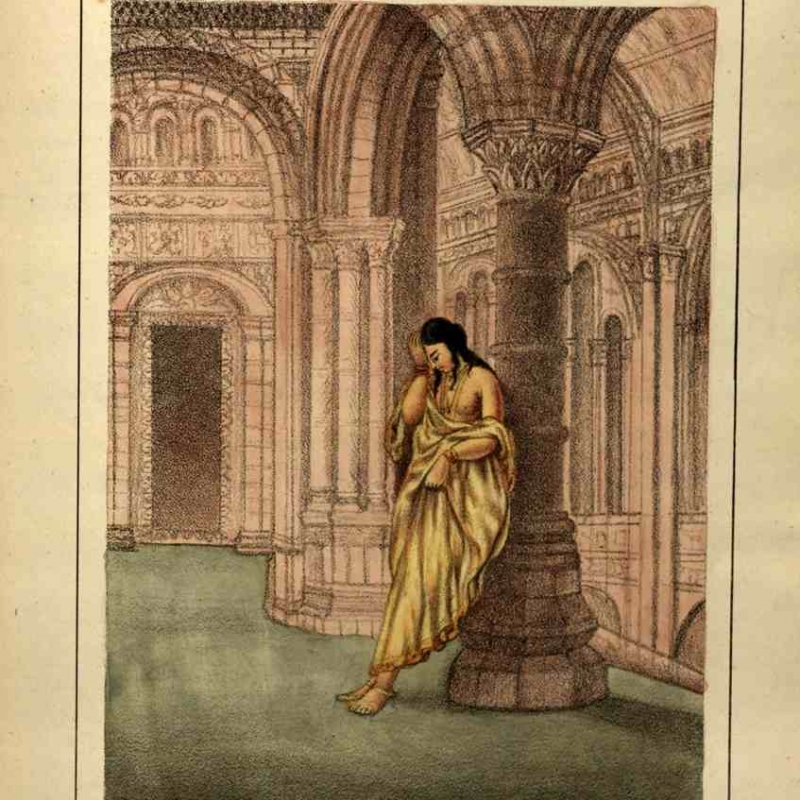

The iconography in Ragamala paintings went through a shift in the mid-sixteenth century, from the depiction of a singular divine icon to chronicling human beings (mostly women) in relation to their environment. Landscapes and architectural settings gained prominence. [10] This change can also be due to the influence of the popular Hindu Bhakti Movement that encouraged the expression of love, longing and devotion for god. [11] There are literary sources, as well, that can attest for the depiction of love as a theme for Ragamala paintings. One such manuscript is Keshava Dasa of Orchha’s Rasikapriya, a treatise on love, c.1591, which shows the various facets of Radha and Krishna’s courtship—the love, quarrels and eventual reconciliations—and contributes to the drama in Ragamalas. [12]

Gaining Ground

During the sixteenth–nineteenth centuries, Ragamala paintings spread across the Mughal empire as painters and scribes accompanied their patrons to various postings. [13] Images erstwhile restricted to the Rajasthani region, now spread towards the south. [14]

It was here in the Deccan that the series became larger and more complex. The theme also changed to depict the heroine in a state of longing and loss—a virahini separated from her soulmate. [15] This was again connected with the Bhakti Movement, as the allegory of ‘love in separation’, akin to the separation of the soul from god was much used.

Watch | Ragamala: Painting from India - Bhaskar Ragaputra of Hindola

In the early nineteenth century, Ragamala miniature paintings also developed a distinct style in the court of Oudh under the patronage of Nawab Shuja’ ud-Daula and his son Asaf ud-Daula. [16] Court artists such as Johan Zoffany and Tilly Kettle (painters of European origin) incorporated Judeo-Christian imagery and devices (such as angels above clouds) [17] into this distinctly Indian genre of miniature painting. (Example here.)

Fading Away

However, soon Ragamala paintings saw a gradual decline. It was only in 1877, writes musician Anirban Bhattacharya in his Sahapedia essay, that the ‘first coherent and complete sequence of the six principal ragas corresponding to the six principal seasons and their corresponding 36 raginis—a theory long prevalent in India, along with their pictorial representation in the form of a Ragamala’ was curated by Raja Sir Sourindro Mohun Tagore, a leading figure in Bengal Renaissance.

The existence of Ragamala paintings across the Indian subcontinent, and even Nepal, attests to its widespread popularity spanning several centuries. The paintings represented a curious confluence of three distinct Indian artistic traditions: poetry, classical music and miniature painting. [18] It is no surprise, therefore, that the imagination of the music that accompanied the imagery of the paintings continues to captivate viewers.

The images in this article have been taken from Sourindro Mohan Tagore’s book, Six Principal Ragas, With a Brief View of Hindu Music. Calcutta: Calcutta Central Press Company, 1875. The digital copies of the images were compiled for Sahapedia by Anirban Bhattacharyya.

This article was also published on Scroll.in

Notes

[1] Exhibition Overview, ‘Ragamala: Picturing Sound’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed April 4, 2020, https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2014/ragamala.

[2] ‘Ragamala, An Introduction’, Dulwich Picture Gallery, accessed April 4, 2020,https://www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk/media/5775/dpg-raga-sbs-6.pdf.

[3] Brihaddeshi is a classical Sanskrit text, dated c. fifth to eighth century CE, on Indian classical music, attributed to Mataṅga Muni. It is the first text to speak directly of the raga and to distinguish marga from desi music.

[4] Exhibition Overview, ‘Ragamala: Picturing Sound’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed April 4, 2020, https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2014/ragamala.

[5] HANCHO, ‘Music to My Eyes: Indian Ragamala Paintings’, Off The Wall, Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar College, Mar 30, 2017, accessed April 4, 2020,

[6] ‘Ragamala, An Introduction’, Dulwich Picture Gallery, accessed April 4, 2020,https://www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk/media/5775/dpg-raga-sbs-6.pdf.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9]Exhibition Overview, ‘Ragamala: Picturing Sound’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed April 4, 2020, https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2014/ragamala.

[10] ‘Ragamala, An Introduction’, Dulwich Picture Gallery, accessed April 4, 2020,https://www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk/media/5775/dpg-raga-sbs-6.pdf.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17]HANCHO, ‘Music to My Eyes: Indian Ragamala Paintings’, Off The Wall, Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar College, Mar 30, 2017, accessed April 4, 2020,

[18] Mr. and Mrs. Edward Wiener, ‘Ragamala Painting of Dhanasri Ragini, c. 1690 Indian’, Kimbell Art Museum, accessed April 7, 2020,