Over the centuries, art has always been a reflection of our society, whose purpose is to bring compassion and warmth to the harsh human world. Therefore, man wishes to beautify his environment with rich flora and fauna, beautiful clothes, paintings, jewellery, etc. The environment not only includes people and their homes but also animals, which plays an essential role in the lives of human beings. It has been witnessed that animals like bulls, horses, elephants were intensively domesticated and special attention was given to their care in terms of food, living conditions and so on.

Among the many animals, the elephant was one, whose gigantic appearance and mountain-like strength (Abu’l-Fazl 1965) were appreciated by the affluent as well as religious institutions. This combined symbolism of power and divinity may have led to extra care being taken towards the decorating of elephants with a variety of ornaments and embellished caparisons. These caparisoned elephants were civilized for veneration, regal processions, hunting, elephant fighting (a popular court pastime), warfare, and for utilization by castle custodians, as a mark of power, both political and religious.

History of Caparisoned Elephants

The relationship of man with the imperial decorated elephant is well represented in Indian history. The earliest example of this is prominently seen on seals excavated from various sites of the Indus Valley Civilization. Take, for example, the famous Pashupati seal, a steatite seal from Mohenjo-Daro, which was one of the greatest findings from the period and was said to have been worshipped by the people. It represents a horned yogi (some scholars speculate this to be a representation of Shiva) in the centre flanked by two animals on each side, one of which is an elephant. Carved near the top right side of the yogi, the elephant appears to have a line coming from the top, which seems to be some drapery or fabric cover. Another 2700 BCE seal (Figure 1) from the national museum collection, presently preserved in the Harappan gallery of the National Museum, New Delhi, has an impression of a horned elephant which appears to be wearing like a cloth on its back.

Similarly, other excavations of stone sculptures and seals from the same period in different regions indicate the use of caparisoned elephants. The remarkable stone sculpture from the Shunga Dynasty, 2nd century BC, showcases similar elephants with accoutrements mounted by a king and servant as is seen in Figure 2. Also, the volumes of Mohenjodaro and the Indus Civilization discuss the same kind of drapery and trappings on an elephant with a manager sitting in the front (Marshal 1931).

Figure 1: Horned decorated elephant, Harappan seal, 2700 BCE. Source: Harappan Gallery, National Museum, New Delhi

Figure 2: King on a caparisoned elephant, Shunga Dynasty, 2nd century BC. Source - Bharut Stupa Gallery, National Museum, New Delhi

Indian mythology has regarded the elephant as a celestial entity due to its association with many deities like Ganesha, Indra, and Lakshmi (often known as Gajalakshmi or the ‘Goddess who rides an elephant’) and so on. Legend has it that during the churning of the ocean (samudramanthan), many ratnas (gems) the ocean offered up many gems and Airavata, the white elephant, was one of them, who thereafter became the mount of Lord Indra, the chief of the celestial beings.

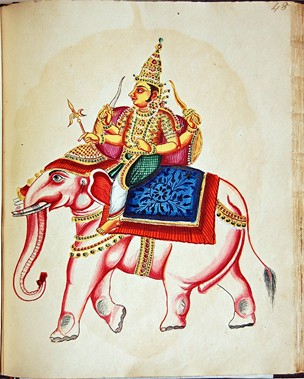

Figure 3: Indra astride the elegantly caparisoned elephant Airavata, circa 1830. Source: ©British Museum - painting/album www.britishmuseum.org

Figure 4: Gajalakshmi, Pala, 8th century AD, Bihar. Source - National Museum, New Delhi

The gouache painting in Figure 3, from the British Museum collection, shows Indra seated on Airavata. As mentioned earlier, the elephant is also associated with Gajalakshmi, the goddess of wealth as it is considered to be a harbinger of fortune and abundance. A remarkable sculpture of Goddess Lakshmi (Figure 4) from the 8th Century AD, Bihar, preserved at the National Museum gallery, depicts the goddess at the centre along with lavishly attired elephants on either side of her.

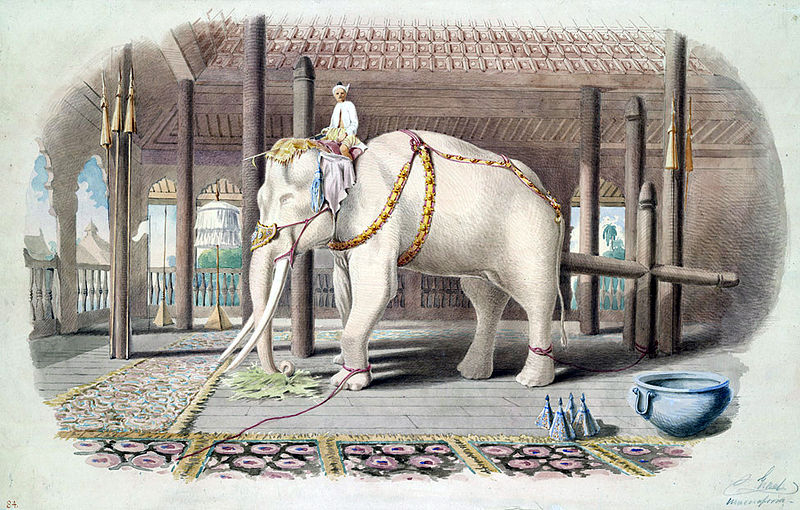

Elephant worship was not restricted to India but was also prevalent in other Southeast Asian countries. According to some European travelogues, in the Siamese tradition too, they venerated white elephants (Figure 5). He was ‘right royally caparisoned in bands of crimson cloth or velvet and gold, studded with large bosses of gold, his ears were decorated with large silver tassels and over his head, he wore an ordinary cloth of gold (Gupta 1983).’

Figure 5: Caparisoned white elephant. Source- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Lord_White_Elephant.jpg

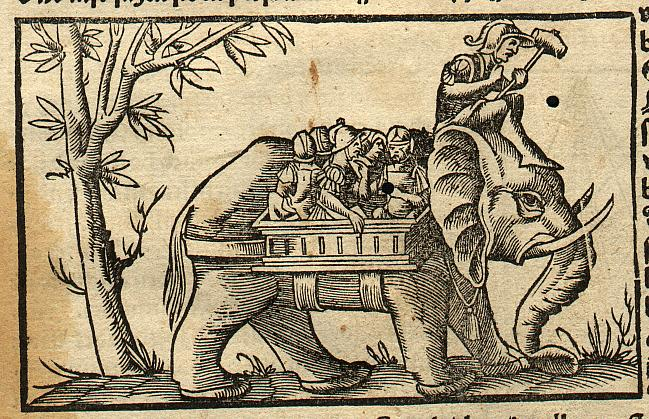

Figure 6: Porus's elephant cavalry, German work, Cosmographia. Source- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Military_elephant.jpg

Likewise, in several Buddhist texts, Buddha as a Chakravartin, or ideal king, possesses seven mythological ratnas including a celestial white elephant decorated in gold trappings, which has been referred as gajakattharaṇā (Davids and William 1921-1925). Numerous stories of Buddha’s former birth mention that the sovereigns as being mounted on the richly caparisoned elephants. They worked with gold and the emperor wore turbans of these gold fabrics whereas the elephants were caparisoned with gold trappings (Mehta 1939). Thus, the practice of decorating an elephant became a prominent means for emperors to exhibit their status and importance by appearing in public on a beautiful colossal being as the animal was associated with the gods.

The use of fully harnessed elephants in warfare was well documented in BC 326 when Alexander the Great invaded India and encountered King Porus’s large army of over the Hydaspes. A major part of this army consisted of fully equipped elephants which created complete havoc among the Macedonian cavalry. Figure 6 shows an image of a harnessed elephant carrying Porus’s cavalry which is illustrated by Sebastian Münster in his 16th century Cosmographia.

The elephant, however, not only captivated the native rulers but also sovereigns such as the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Dynasty. They believed that the value of a good elephant was equal to five hundred horses (Abu’l-Fazl 1965). During these reigns, the employment of richly-festooned elephants for royal processions and warfare was booming. The historian G.N. Pant mentions the war accoutrements of the elephant and describes ‘necklaces as vaijayanti and kshurapramata as litter and housings as the ornaments for an elephant’ (Pant 1978). Abu’l-Fazl, the trusted noble of the Mughal emperor Akbar, details in his Akbarnama the process of selecting and classifying the imperial elephants.

Akbar commenced proper regulations to care for the well-being of his animal subjects. Special karakhanas like pheelkhana and zinkhana were made for them for which accounts were maintained. Pheelkhana was the place where seven different classes of elephants were looked after. Thereafter, two to five and a half servants were appointed to each elephant depending upon its size, gender and class, out of them one to three and a-half servants were known as meths, where a half is a boy and the rest were men who assisted in caparisoning the elephant. The other servants were mahawats, i.e., elephant rider, who sat on the neck of the animal and the second one the Bhoi, who sat upon the rump of the elephant (appointed to only large sized elephants). The zinkhana was the house where the saddles and other belongings of the elephants were kept and provided to the meths when required (Abu’l-Fazl 1965).

Possessing such caparisoned giant animal became a mark of pomp for the emperor and it was an established practice of giving and receiving them as gifts. On December 2, 1528 AD, Babur had presented, among many other items, ten war elephants with accoutrements to Askari, his son (Beveridge 1922). During the coronation of Maharaja Takht Singh in Vikaram Samvat 1901 (1844 AD), ‘one elephant jhul comprised of gold taash fabric, red cotton lining and orange colour fringes’ was recorded along with takiya, howdah and another piece of jhul made with red velvet embellished with zardozi embroidery (Inventory Bahi V.S. 1901).

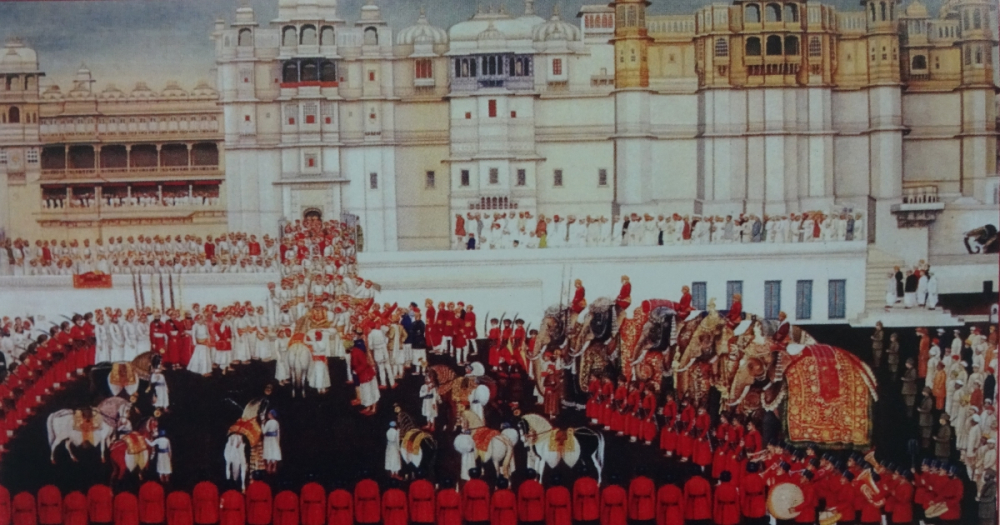

The famous Gangaur festival of the Rajputs is celebrated with great devotion by the womenfolk. The festival includes a huge procession which commences from the palace. Figure 7, a miniature wall painting from the Juna Mahal of Dungarpur portrays a Gangaur procession, where the women carry the goddess Gangaur (Gauri, wife of Lord Shiva) on their heads followed by Maharaja Udai Singh riding on a fully arrayed elephant along with Khuman Singh. Much like the aforementioned festival, the festival of Holi was a time when the king used to appear in public mounted on a caparisoned elephant and watch his subjects enjoy the festivities.

One such instance is depicted in the miniature painting from the Marwar dynasty (Figure 8), where, Maharaja Man Singh (1801-1843 AD) presents himself along with his servants to the public for the Holi celebrations. He appears on a lavish elephant, which has been ornamented with numerous necklaces, bells, earrings, pakhar (head covering), jhul, etc. These elephants were not merely a source of entertainment or a mode of transport, but as mentioned earlier, were also worshipped. The worshipping of an elephant known as gajapuja was celebrated with as much pomp and ceremony as a festival. This miniature painting of the Mewar School depicts Maharana Bhupal Singh of Mewar worshipping fully attired elephants and horses on the occasion of Dussehra in 1939 AD (Figure 9) (Purohit 2005).

Figure 7: Gangaur procession, Vikram Samvat 1943 (1886 AD), Juna Mahal, Dungarpur

Figure 8: Maharaja Man Singh’s Holi procession, 1810 AD. Source: ©Mehrangarh Museum Trust, Jodhpur

Ornamental Trappings of Elephants

Elephants were decorated for various purposes as mentioned above, which later become customary for the crowned heads, as it represented their status and influence. The decoration was as elaborate as that of the emperor. Therefore, they had numerous ornaments for each and every body part, starting from the head and down to the toe. Abu’l-Fazl writes in Ain-I-Akbari that ‘it is impossible to describe all the ornamental trappings of the elephant’, but he still managed to document some of the ornaments used for decorating the various body parts.

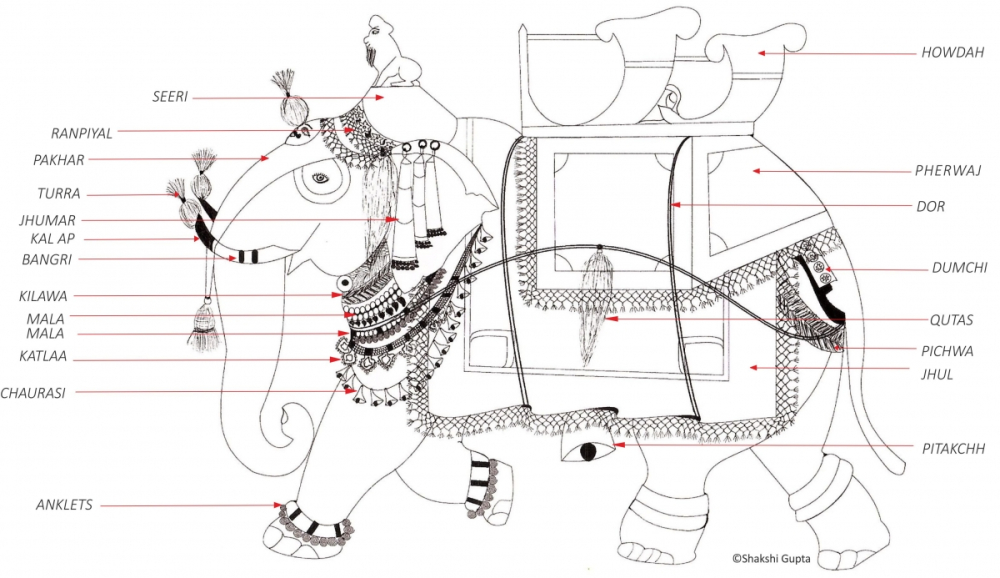

Figure 9 depicts a fully attired elephant with numerous ornaments and clothes for every body part. Starting from the head the elephant was covered in three layers consisting of pakhar, seeri and ranpiyal. Pakhar is armor made out of steel or iron plates, with the sun depicted in the centre, considered to be an eye of the deity. It was mostly worn in wars; otherwise, the second layer, i.e., seeri, depicted in the figure was worn alone. It is a decorative covering made from the rich cloth, embroidered in zardozi and trimmed with loose tassels. Its size and shape vary according to the size of the elephant. Abu’l-Fazl refers to seeri as gaj-jhamp in Ain-I-Akbari and writes that ‘it is made of three folds of canvas, put together and sewn, broad ribbons being attached to the outside’. On top of that was fastened the ranpiyal, which is a decorative band for the forehead, made of brocade or velvet, and from the hem of which ribbons or qutas are hung down. Qutas are the decorative hangings made from the tail of Tibetan Yak. These were hung down to the head, to the belly and sometimes to the tusks as well.

Figure 10: Caparisoned Elephant. Source: Author

Thereafter, the elephant’s back was covered with jhul, a carpet-like large rectangular cloth, which was flung down on both sides of the animal (Gupta 2017). The Hindi Shabdsagar dictionary of Shyamasundara Dasa mentions the word jhul to convey the covering for both elephants and horses which was often made of velvet with karchobi embroidery on it. The embroidery was largely done with slender gold and silver wires all over the span of the fabric. It also helped in reducing the chafing of the elephant’s skin. To further upgrade the lavishness, pitkachh, a bell with a chain was fastened on either side of the elephant, which fell below the belly.

Other than this, gold and silver studded ornaments along with some twisted ropes were worn by them, like jhumar for the ears, while the neck was adorned with different styles of trinkets like mala, katla and chaurasi. Mala and katla are ornamental neck pieces which consist of big gold medallions to which loose dangles are hung, whereas the chaurasi consists of a number of bells attached to a piece of broadcloth and hung down nearly up to the knees of the elephant. It looked ornamental and grand. The twisted ropes were used to control the elephant and bind the trappings. The twisted ropes too have specific names such as kilawa, eight fingers broad, fastened at the throat and pichwa four fingers wide, and tied beneath the tail. Dumchi is another ornament for tail decoration, which was tied over the pichwa. Anklets, perhaps known as kara in Marwar, were also worn by them to enhance the beauty (Bahi Hathiyan ri pheelkhana talake ri bahi. V.S. 1925).

The decoration did not stop here; they had ornaments for the ivory tusks as well. These were adorned with bangri, round rings made from metal-like iron or brass in number, along with a tusk protector called the kalap (Bahi Hathiyan ri pheelkhana talake ri bahi. V.S. 1925). The kalap is similar in shape to the tusk and was worn to strengthen it.

After all, this decoration comes to the seating arrangement for the king, for which the howdah, a carriage, was placed at the top of the jhul made from either metal or wood. The sidebars of the howdah were covered with another cloth, which was referred to as pherwaj, a howdah coverlet. It came in a set of three pieces, where two were square in shape and the third one was rectangular. The square one covered the sidebars and the rectangular one covered the back of the howdah.

Finally, the trappings were secured with another twisted rope referred to as dor in the Ain-I-Akbari and bandhan in the Bahi Hathiyan ri pheelkhana talake ri bahi. V.S. 1925. This would go around the body of the elephant, tying the trappings together, so that it did not move from its place during the movement of the colossal being.

Elephant decoration, therefore, particularly with the imperial ornaments, twisted ropes, and a gold cloth (jhul, seeri, pherwaj) was an evolved, vast and well-defined art.

Present Status

In the 19th century, when the world was getting modernized with rapid technological advances, India was being ruled by the British. It was under them that a massive spectacle is known as the ‘Court of Delhi’ was organized in 1877, 1901 and 1911, which was no less than a festival. The Viceroy along with all the 48 kings from across the country reached the coronation park, mounted on lavishly attired elephants covered with gilded cloths to salute the new Emperor and Empress of India. This was the last time that Delhi witnessed such a magnificent procession.

Thereafter, the royalty began losing their political clout and consequently, the elephant decorators lost the patronage of this affluent group, which gave rise to commercialization. It was the time of the Industrial Revolution, and technology began replacing old systems adversely impacting the art, which was a source of income for many an artisan. The impact of this has been seen in many art sectors such as clothing, jewelry, architecture, transport, etc. The use of motor vehicles became the fashionable and convenient way to commute. It resulted in a decline in the use of animals, particularly harnessed elephants. Also, the skills and cost of maintenance for such giants were become increasingly hard to keep up with.

Yet, customs in India seldom die out completely. Presently bedecked elephants are saved for grand occasions and religious festive processions. The art has been preserved in different ways. For example, there is Hathi Gaon, a village established for elephants, located 12 Km away from the main city of Jaipur, where nearly 150 elephants live with their families and mahavats (elephant riders). Elefantastic is one of those families who reside there along with their 24 elephants and continue the craft of decorating and grooming elephants till today. But the decoration focuses on body art instead of jewellery and clothing. Body art includes body painting, which is one of the major forms of decoration and lasts for several hours and weeks on the elephant’s body. The exquisitely done art work on their skin, starts from the head, down to the lower section of the trunk, followed by the ears and then onto the forelegs and sometimes the back as well.

The artisans who are mahavats also, delineate motifs like leaves, flowers, figurines, animals, birds, etc., inspired by nature and their surroundings. These motifs are drawn with a thin white colour paste, made from a mixture of the rough of white sandstone and water. Then, these motifs are filled with nature’s most vibrant colours, made from the rough of coloured sandstone and water. These paints are applied with the help of a bamboo stick where one end is cut at an angle to carry out both general and detailed art work. Later, these painted elephants are decked up with the traditional jewellery and clothing like jhul, seeri etc., for special occasions.

Through the historical background and archaeological excavations, it seems certain that the practice of caparisoning elephants was germane to India. From being a being to be worshipped, the elephant soon came to be associated with power and became a status symbol for its masters. Later, the use of these beautiful beasts declined and we are now at a juncture when it is hard to imagine let alone relive the traditions associated with these animals. Today, they are used as tourist attractions and in some places continue to be at the heart of ritual worship. Hence, the caparisoned elephant continues to hold a unique position in the lives of human beings, albeit with a slightly dimmed grandeur.

References and further readings

Abu’l-Fazl. 1965. Ain-I-Akbari. Translated into English by Blochman. New Delhi: New Imperial, Book Depot.

Bahi Hathiyan ri pheelkhana talake ri bahi. Vikram Samvat 1925 (1869 AD). Jodhpur: Maharaja Man Singh Pustak Prakash Shodh Kendra, Mehrangarh Fort.

Batuta, Ibn. 1933. Ibnabatuta ki Bharat Yatra. Translated into Hindi by Dinesh Sharma. India: National Book Trust.

Beveridge, A.S. 1922. The Babur Nama in English (Memoirs of Babur). London: Luzac & Co.

David, T.W.Rhys and William Stede. 1921-1925. Pali - English Dictionary. London: The Pali Text Society.

Gupta, Charu Smita. 1986. Zardozi: Glittering gold embroidery. New Delhi: Abhinav Publication.

Gupta, S.K. 1983. Elephant in India Art & Mythology. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications.

Gupta, Shakshi. 2017. Metal Embroidery on Elephant Trappings (Jhul). Textile and Clothing Research Center biannual e-Journal 1 (2).

Inventory Bahi - Physical Verification of objects during the Coronation of Maharaja Takht Singh. Vikram Samvat 1901 (1845 AD). Jodhpur: Maharaja Man Singh Pustak Prakash Shodh Kendra, Mehrangarh Fort.

Mehta, R.N. 1939. Pre-Buddhist India. Bombay: Examiner Press.

Marshall, Sir John. 1931. Mohenjodaro and the Indus Civilization, Volume II. London: Arthur Probsthain

———. 1931. Mohenjodaro and the Indus Civilization, Volume III. London: Arthur Probsthain.

Nossov, Konstantin. 2008. War Elephant. United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing Ltd.

Palmer, Greta Paradine. 2002. Jhools in the Dust. Great Britain: Wilton 65.

Pant, G.N. 1978. Indian Archery. New Delhi: Agam Kala Prakshan.

———. 1989. Mughal Weapons in the Babur Nama. New Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan.

———. 1997. Horse and Elephant Armour. New Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan.

Purohit, Dr. Rajendra Nath. 2005. Mewar Darikhana ke Riti-Riwas Avam Sanaskar. Jodhpur: Rajasthan Granthagar

Saxena, Rajendra Kumar. 2002. Karkhanas of the Mughal zamindars: a study in the economic development of 18th century Rajputana. Jaipur: Publication Scheme.

The Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri. 2006. Translated by Alexander Rogers. New Delhi: Low Price Publication.

Verma, S.P. 1978. Art & Material Culture in Painting of Akbar’s Court. New Delhi.

Verma, Tripta. 1994. Karkhanas under the Mughals, from Akbar to Aurangzeb: a study in economic development. New Delhi: Pragati Publication.

Watt, Sir George. Indian Art at Delhi 1903. India: The Superintendent of Government Printing.