The spiritual journey I wish to consider here is, in fact, a story of several journeys, spanning a vast historical time. It is the story of an ancient sage, Bodhidharma, who travelled across the seas from his native Kanchipuram in the sixth century to China, preaching the word of Lord Buddha, like many other well-known Indian masters. It is the journey of an idea, ‘dhyana’ or contemplation, which points to another kind of journey, a journey to the inner recesses within one’s own self. Dhyana itself has this sense of travel. Its roots are ‘dhi’ or mind and ‘yana’ or movement. So dhyana is the journey of the mind. In its travels through China, the idea of dhyana blended well with the already well-established doctrine of ‘Tao’ or ‘The Way’ associated with the philosopher Zhuang Zi. This, too, taught the value of contemplation, the virtue of silence, of stillness, becoming aware of the essence and nature of things. What emerged out of this blend was ‘Chan’, a Chinese alliteration of the word ‘Dhyana’, which represents an Indian concept layered with a Chinese sensibility. And when ‘Chan’ crossed the seas into Japan, it became Zen, enriched by yet another layer of refinement and spiritual content.

It is, however, important to realise that all forms of Buddhist thought, including Chan and Zen, take the experience of enlightenment of Lord Buddha as the central narrative. Zen understands itself, just as Chan does, as a part of the tradition that is rooted in this great experience. Thus, in the Zen tradition, Gautam Buddha is considered the seventh patriarch, with earlier incarnations before him. Bodhidharma is the first patriarch of Zen in China, but also the 28th in a direct line of descent from Buddha himself. In the Zen tradition, there is a direct transmission of the enlightenment experience from one generation to the next, but only when a successor is deemed ready, working through his own practice of dhyana and awareness of existential reality.

The practice of dhyana associated with Buddhism is, of course, rooted in the much older yogic tradition, which was later codified by Patanjali in his Yoga Sutra, composed sometime around the second or first century BC. Its key elements include asana, or sitting in particular postures, pranayama, or modes of breathing, and dharana or fixing the mind to an idea before achieving Samadhi or an abiding stillness of the mind. These elements remain in the Buddhist tradition as well as in the manifestations of this tradition in Chan and Zen. In all these versions, dhyana involves the observation of one’s own thoughts and must be done in silence (maunam), stability (dhiram) and detachment (vairagyam). It is these fundamental elements which Bodhidharma took to China probably in the sixth century AD, and they took root and flourished first in China and then in Japan in the subsequent centuries.

Little is known about Bodhidharma in India itself, though he is revered in China, where he is known as Damo, and in Japan, where he is known as Daruma. From the sparse records that are available, we know that Bodhidharma was the third son of a Tamil Pallava king in Kanchipuram. He sailed to China to propagate Buddhism at the instance of his teacher, Prajnatara. He finally settled down at a monastery in Shaolin, where he sat deep in meditation for 13 years in front of a wall. At the end of that period, he is said to have lost the use of his limbs. That is how he is depicted in Japan—without hands and feet.

Image 1: Bodhidharma (Japanese: Daruma) was a Buddhist monk who travelled from India to China to propagate Zen Buddhist teachings there. Executed in cast-iron during the Ming period (1368–1644) in China, the sculpture (dimensions: H. 36 in; W. 17 in; D. 11 1/4 in) shows Bodhidharma seated in meditation. Photo credit: The Met collection https://www.metmuseum.org/

The patriarchs who succeeded Bodhidharma introduced two new elements. One was the idea of ‘sudden enlightenment’ associated with Shen Hsiu and further developed by Hui Neng. It corresponds to the concept of ‘Satori’ in Japan. This contrasts with the theory of incremental progression which eventually leads to enlightenment. However, even in the case of Satori, it is only when the mind has been stilled and made ready through rigorous discipline and the practice of dhyana that it may experience enlightenment. This may occur even while performing the most ordinary tasks, like catching fish, drawing water from the well or splitting bamboo to use as firewood. In Japan, these two schools became known as the Soto and the Rinzai, with the latter stressing the Satori experience.

The Rinzai school is also associated with another unique feature of Zen that is the use of koans, or cases. Koans are paradoxical sayings or sometimes baffling questions and answers between a master and disciple. They are riddles that have no rational solution. They can only be realised not resolved. The purpose is to make a seeker after truth become aware of the limits of rational thought and analysis. Self-awareness or the experience of existential reality can only be achieved by transcending rational thought. A koan is meant to drive the mind into a corner, into a dead end, so that there is no escape but to make that dangerous leap over the wall we ourselves construct through rational thinking.

This brings to mind what the great poet T.S. Eliot alluded to in The Wasteland:

My friend, blood shaking my heart,

The awful daring of a moment’s surrender

Which an age of prudence can never retract

By this, and this only, we have existed.

While it is Rinzai which is associated with the use of koans, they are part of the Zen tradition practised by other schools as well. There are koans that are ascribed to Lord Buddha himself. In one episode, Lord Buddha held up a stick in his hand before the assembled congregation. After some time, one of the disciples walked up to him, took away the stick and broke it into two. The Buddha smiled. Now there may be many interpretations of this story and we may struggle to find a meaning embodied in it. But the reality is that there is no answer to this strange encounter. Zen masters give their students one of the many koans to meditate on once they have reached a certain level in Zen Practice. How they ‘solve’ each koan gives the master a means of measuring spiritual progress but also to create a mental state which is ripe enough to receive enlightenment.

Both in China and Japan, Zen had a significant impact on art and culture. In China, it led to the popularity of monochrome painting, new styles of calligraphy and poetry. What distinguished these forms were their impressionistic expression as opposed to a faithful and meticulous representation of objects. There is a certain spontaneity and free spirit that seems to underlie these art forms. The subjects are often commonplace and ordinary but are suffused with a heightened perception that Zen brings. In this context, it is worth narrating the words of the Chinese Zen master, Ching Yuan of the Tang dynasty:

Thirty years ago, I began the study of Zen, I said, Mountains are mountains, waters are waters. After I got insight into the truth of Zen through the instructions of a good Master, I said, Mountains are not mountains, waters are not waters. But now having attained the abode of final rest, I say, Mountains are really mountains, waters are really waters.

And this encapsulates what Zen is all about.

These characteristic features of Zen art find their finest expression in Japan, whether it is in monochrome painting, running hand calligraphy, the minimalist Zen garden, the haiku form in poetry or the ‘No’ theatrical form. For example, a haiku composed by Basho reads thus:

Moonless night . . .

a powerful wind embraces

the ancient cedars

Japanese music for the traditional Shakuhachi flute incorporates the same principle of seeking the essence of a natural phenomenon, such as sound, and through it becoming aware of its ultimate reality which is silence. There is a saying in Japan that sounds take their being from silence and return to it; the lines in a painting or the strokes in calligraphy take their being from emptiness and return to it.

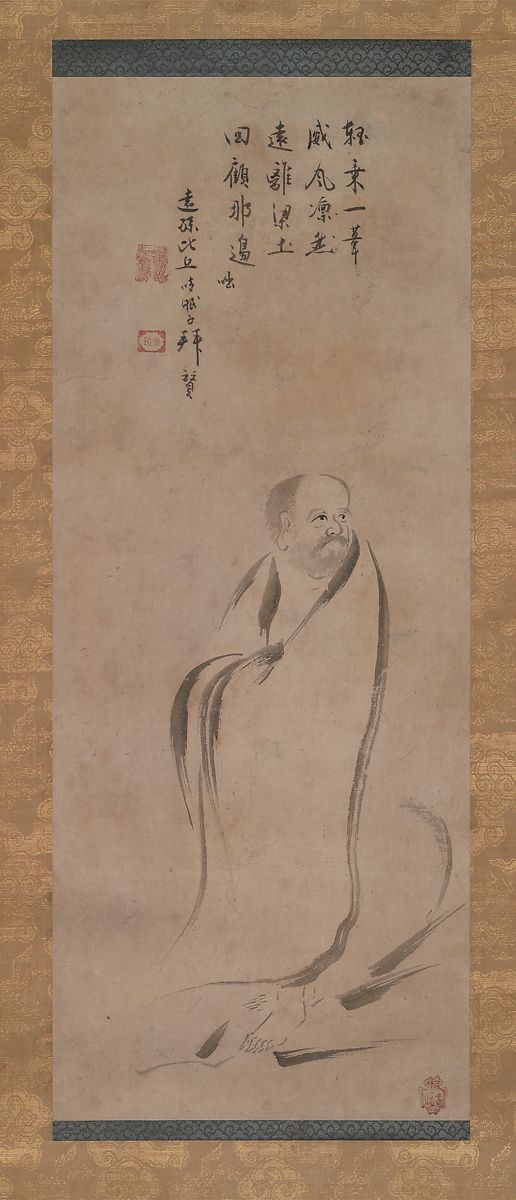

Image 2: Executed using long, flowing strokes of ink on a hanging scroll, this work by Kano Sōshū (Japanese, 1551–1601) depicts Bodhidharma sailing up the Yangtze River on a reed to propagate his teachings across China. The painting can be dated back to the Momoyama period (1573–1615) and the calligrapher was Gyokushitsu Sōhaku (Japanese, 1572–1641). Photo credit: the Met collection https://www.metmuseum.org/

What we witness here, therefore, is a fascinating journey, where a revolutionary idea of seeking truth from within oneself, which germinated in India, wound its way to China and Japan, gathering local colour, fragrance and sensibility. In this long journey through time and space, the Indian beginnings continue to shine through the later, more local accretions. An encounter with Chan in China or Zen in Japan brings to an Indian an intuitive awareness of ideas and images that lie embedded in the deep recesses of his own mind.

And this brings me to my own encounter with Zen as I travelled, in my diplomatic assignments, to China and then to Japan, picking up pieces of a story, still dimly perceived, but which attained a certain clarity during the days I spent at the San-Un-Zendo, a Zen meditation hall in Kamakura on the outskirts of Tokyo, during the years 1987 to 1989.

In 1987 in Tokyo, I had a chance encounter with a Zen master, Yamada Roshi (Roshi in Japanese stands for someone who is an adept or a guru). How I came to meet him is a story of coincidences. Our Embassy was hosting an audit team from India to look into our not too efficiently managed finances. The team was led by an extremely devout Tamil Brahmin, complete with sandalwood paste smeared on his broad forehead. When he came to see me, I asked him if there was anything we could do to make his stay in Tokyo pleasant and worthwhile, beyond his auditing activities. The idea was to deflect him, if possible, from too intrusive a scrutiny into our somewhat shaky accounts. My guest had a simple request. Could I arrange for him to receive the blessings of an accomplished Zen master? For the reasons I mentioned, it was imperative that I deliver on the request. But where would I find a Zen master? Several attempts to locate one through our helpful Japanese staff and some Japanese friends we knew drew a blank. I was getting quite desperate when I suddenly remembered that I knew a Japanese Buddhist monk, Nakamura-san, whom I had met in Geneva some years back when I was an Alternate Representative to the UN Conference on Disarmament. Nakamura-san was part of the entourage of the well-known Fuji Guru of the Japanese Nichi-ren sect, who worked and prayed tirelessly for a nuclear-weapon free and peaceful world. In his monk robes, and followed by his devoted disciples, he would take out processions in cities around the world, beating a round drum, chanting Buddhist hymns and praying in front of parliaments, the UN premises in Geneva and New York, and other government offices. It was in Geneva that I became familiar with Fuji Guru who had a special affection for India. Nakamura-San was almost always present and we became acquaintances, if not friends. In my state of panic, I managed to find his visiting card, and was relieved when he responded to my call. I put my problem before him and asked for his help. He laughed, saying that the Nichi-ren sect he belonged to had very little to do with Zen, but, in any case, he would make some enquiries and get back to me.

A few hours later, he called back to say that, through his network, he had been able to locate and contact a true-blood Zen master in Kamakura just outside Tokyo, but since the master also ran a charity hospital almost across the street from our Embassy, he had agreed to meet our audit team leader at his offices in the hospital itself. That very evening, I took our important guest to meet the master in his chambers. Imagine our surprise, when we were ushered into a large but modest office room, to be received by a distinguished looking Japanese gentleman, dressed in a dapper Western suit. He was accompanied by his wife, an elegant lady also dressed in Western clothes. I thought, perhaps, these were the advance guard and that the Roshi himself would appear later. But then the gentleman extended his hand to welcome us in fluent English and identified himself as Yamada Roshi, the very object of our mission.

Yamada Roshi and his wife were extremely warm and welcoming. The master had an animated conversation with our audit team leader, explaining to him some finer points of the Zen tradition. I hardly remember anything of that conversation. I was not paying attention, happy that I had delivered on my promise and that this may deliver a more benign report on our Embassy’s finances. But soon the meeting came to an end. My companion bent low to receive the blessings of the Roshi. I maintained an amused distance from this scene. But what stuck in my memory was what the Roshi said to us, that he was honoured that a son of the land that gave birth to Lord Buddha had come to him to seek wisdom.

Yamada Roshi then turned to me and gave me a copy of his book in English on Zen: The Gateless Gate. He said I might find it interesting. He added that he had a traditional zendo or meditation hall in Kamakura, whose address he gave me, where I was welcome any second Saturday of the month, to see for myself what Zen meditation was all about. I made some polite noises about availing of his kind invitation and then promptly forgot about it. The audit team was kind, the danger was past and all was well with the world.

It was a couple of months later that I chanced upon the book Yamada Roshi had gifted to me while looking for something to read on a lazy weekend. And what I read was both familiar as well as novel, and my curiosity was fully aroused. Next weekend, in the middle of the month, I took a train early in the morning to Kamakura, and after a few wrong turns, found the Zen hall, called San-un-Zendo, in one of the narrow lanes in the old part of town. It was a quaint old Japanese style wooden building with a small pebble-strewn garden in front.

As I opened the gate and went in, I was face to face with a smallish hall, open to the outside, where some 10 people were sitting in two rows on the floor, on cushions, cross-legged, deep in meditation. There was an old gentleman, dressed in traditional Japanese clothes, holding a small stick like a ruler in his hand, quietly walking up and down between the two rows of Zen practitioners. When he saw me, he motioned to me that I should take my shoes off and enter. When I did, he pointed to an empty cushion and asked me to sit down and join the others in meditation. He thought I was one of the pupils and had come late. Since silence had to be maintained, I was unable to explain that I had come not to meditate but to meet Yamada Roshi.

Image 3: In the typical style of pre-modern Japanese portraiture, this set of three hanging scrolls depicts a Zen master holding an ‘admonition staff’ (sheppei) set against a backdrop of a Chinese-style landscape. The painting was made by Unkoku Tōeki, between the late 1620s–1644, using ink on paper; the calligraphy has been credited to Ten'yū Jōkō (Japanese, 1586–1660). Photo credit: the Met collection https://www.metmuseum.org/

The next ten minutes, until the session ended for a short break, I was in a state of panic. I tried to imitate my neighbour next to me and keep my eyes closed. I soon felt a gentle tap on my shoulder when the teacher used his short stick as if to prod me. This seems to have disturbed some of fellow practitioners who looked somewhat quizzically at me. When the session was over and we all stood up, the teacher came up to me and asked if I was a newcomer. I said I had come to meet Yamada Roshi. He then realised what had happened and laughed. ‘I hope I did not make you too nervous!’ He then took me upstairs to another room, with tatami mats, but otherwise bare, where Yamada Roshi sat cross-legged on a cushion on the floor, but this time in a traditional Japanese loose-fitting kimono. He welcomed me with a smile and asked me to sit down on another cushion, facing him. When we were alone, he asked why I had decided to come. I answered that I just happened to read the book he had given me and became curious and interested and, therefore, decided to pay a visit. I also related my recent embarrassing experience in the zendo below, apologising for disturbing the very solemn proceedings.

Yamada Roshi seemed amused. He again welcomed me and added that he had been expecting me. I found this intriguing and even somewhat far-fetched. I then narrated to him the series of coincidences that had brought me to his zendo.

Yamada Roshi dismissed the idea that our encounter had been only a coincidence. He said that in Buddhism nothing was chance, every happening is the result of one’s karma and one’s sanskar or inborn traits. He then proceeded to explain that unlike in other systems where spiritual evolution is seen as a progressive abstraction or withdrawal from the phenomenal world, Zen enables its practitioners to incorporate spirituality in everyday life, benefiting oneself as also those around us. He took me back to Lord Buddha’s various experiments with different schools preaching ‘nirvana’ or enlightenment before he came up with a philosophy that brought salvation within the reach of the laity. After attaining nirvana, the Roshi said, Lord Buddha looked at the world around him and exclaimed, ‘Subarashi! Subarashi!’ or ‘What a marvel and a wonder this world is!’ The point that Buddha wished to convey was that in order cultivate spirituality and eventually gain enlightenment, the path to be taken was not withdrawal from this wonderful world but rather to learn to live within it, to find joy, a sense of harmony and a continual sense of peace within ourselves. It is this experience that Zen practitioners seek to recreate, each for himself.

The Roshi asked me whether, having briefly experienced the practice of Zen at the zendo, I would wish to be initiated and continue the practice. I nodded and soon found myself back at the zendo below, where the teacher instructed me in some of the basic exercises, and later in future sessions took me through six initiatory lectures as well as more complex breathing and meditation exercises.

In Zen meditation exercises, one sits in a lotus (padmasan) or a half-lotus position, but facing a blank wall, the left hand placed over the right in one’s lap with the thumbs touching each other gently. This recreates the tradition of Zen’s first patriarch, Bodhidharma, who also sat in meditation opposite a blank brick wall.

Image 4: Fashioned as a sentoku tsuba (sword guard), this work of art shows Bodhidharma facing a cave wall in meditation; the motif is called Menpeki Daruma (面壁達磨) in art history. The artist Tsuneshige, who was originally a lacquer artist, used copper alloy (sentoku), copper-gold alloy (shakudō), and gold to make this tsuba; dated to ca. 1615–1868. Photo credit: the Met collection https://www.metmuseum.org/

Zen meditation requires the practitioner to keep his eyes open, focused on a point on the wall, roughly in line with one’s navel. This may appear strained at first, but then it becomes, fairly soon, within a couple of weeks, quite natural and comfortable. Keeping one’s eyes open is important. It ensures that one remains aware of the world around us even while seeking a calmness of spirit.

The breathing exercises are simple. One begins with breathing in and out in cycles of 10, consciously slowing down the count. Keeping the count is the first exercise in concentration. The mind inevitably wanders off in the middle of the count. One needs to gently bring it back and start again. One should accept it as natural that the mind will wander. After a period of practice, it will wander less and less. Yamada Roshi would warn against straining too much to concentrate the mind. The mind is like a fistful of sand. The more one tries and holds it, the quicker it will slip through your fingers. So, hold it gently.

The counts have some variations. Once you are able to count your inhalation and exhalation in cycles of 10, without too frequent a wavering of attention, the master directs you to count only your inhalation (builds up concentration) and then only the exhalation (to dissolve the ‘knots of tension’). Eventually, you should be able to just observe your breath, which has by now acquired a much slower, gentler rhythm, without the scaffolding of the count.

Reaching this stage of practice begins to give one a sense of how a thought arises in the mind and then flows through, sometimes in quite a random manner, to other related thoughts, memories or associations. While sitting at meditation, you may be distracted by the bark of a dog, which may lead your mind to think of your own pet dog which died a few years back. This, in turn, may lead you to think of your child who dearly loved the dog, and this, in turn, may remind you that the child’s school fees need to be paid, and this may make you think of your bank balance and so on. What Zen practice does is to enable you, as if you were sitting on your own shoulder and watching as a witness, this stream of consciousness, of being able to trace the current train of thought to its origin, before you resume watching your breath again.

Yamada Roshi taught that most problems, particularly in interpersonal relations, arise precisely because we get caught in a chain of cause and effect. A person abuses us in anger. Our reflexive reaction may be to abuse him back, perhaps in a more derogatory manner. Each feeds on the other’s anger. This may set up a rising crescendo of abuse which may end in violence. What Zen will do is to give you a few seconds of reflection before you react to any stimulus. In most cases, on second thoughts, you may not react because you realise it is not worth your while. And thereby you avoid an entire cumulative chain of action/reaction that may end up in a crisis, in a break-up of human relationships and sometimes even in crime. Knowing your mind, being able to watch the process through which thoughts arise, gives you the ability to control it. This is of critical importance because you cannot control your environment and those around you, but you can control your own reaction to them.

Another key benefit comes from being able to regulate one’s breathing. Here Zen is not much different from Yoga. Breathing is an involuntary activity, but it can be made into a voluntary, controllable activity through breathing exercises. Yamada Roshi would describe breathing as the ‘master valve’ or the ‘master regulator’ of the human mind-body complex. Through control over one’s breath, by making breathing a much slower rhythmic activity, one can slow down the body’s metabolism. The human body has inherited from its hunter’s past, the ability to respond to danger or to hunt for prey by pumping adrenaline into the bloodstream. This quickens one’s breathing, makes the heart pump blood into the system at an accelerated rate and this pump-primes the body to be prepared to face any emergency or crisis. This may be in order to run as fast as possible to escape danger or to pursue a fast-moving prey to ensure the next meal. However, to keep pumping adrenaline into the system when no physical risk looms over a person merely raises the metabolic rate, attacks the body’s tissues and results in a host of psychosomatic problems. This is stress. The mind responds to psychological challenges such as observing deadlines, competing with others to move ahead or emotional crises such as marital discord, by reacting as if there was physical danger. The resultant physical changes in the body, instead of helping cope with what are essentially emotional or psychological challenges makes them worse by heightening the sense of crisis and even danger. The way to deal with such challenges is through calm reflection, by locating the issues in the larger canvas of life, and in refusing to be drawn into an action-reaction process.

Yamada Roshi would describe stress in his own uniquely contemporary fashion. One’s body and its resources are like a motor vehicle. You engage the gears, press the accelerator and the car moves forward. If you need to overtake another car or have to speed up to get to your destination quicker, you press the accelerator. This is the equivalent of pumping adrenaline into your system. However, in a modern, urban setting, the pattern of our living is like a stationary car; it is not going anywhere, but instead of idling the engine, we still keep pressing the accelerator, sometimes right down to the floor. The car is all revved up, its RPM counter is rising, but it has nowhere to go. This causes undue wear and tear on the engine and quite unproductively because the car remains where it is. We need to learn to keep our mind-body system in ‘idling mode’, and this we can achieve precisely through the meditation and breathing techniques prescribed by Zen.

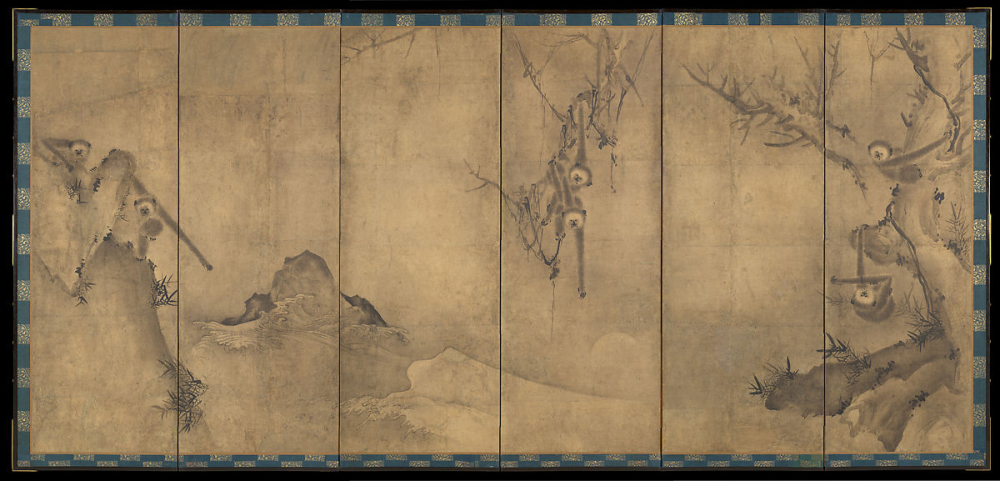

Image 5: Sesson Shūkei (ca. 1504–ca. 1589), a Zen monk-artist, painted a six-panel screen with gibbons reaching for a reflection of the moon to reveal a popular Zen paradox: when you wantonly or over-anxiously reach for enlightenment, it usually eludes you. The ink painting can be dated back to ca.1570, the Muromachi period (1392-1573). Photo credit: the Met collection https://www.metmuseum.org/

What does increased concentration achieve? Again, Yamada Roshi would compare the human mind to a receiving and transmitting communication system. With better concentration, the mind is able to ‘tune in’ to more and more subtle wave patterns around us and make us more sensitive to any environment. Similarly, with better concentration, our minds, perhaps our entire being, emit more subtle, more refined wave patterns which create a sense of comfort and harmony among those around us. Our comprehension increases, we become more articulate and effective interlocutors, we become more sympathetic and considerate to those around us. We become more humane.

In another aspect, Zen teaching is remarkably close to the Bhagavad Gita. Zen teaches that we cannot control the environment around us, but we can control and regulate our response to that environment. Success is not location-specific. It is temperament-specific. Knowing that we cannot control the environment also enables us to look at success and failure more dispassionately and with equanimity. It is quite likely that we may do everything right and still fail for reasons beyond our control. On the other hand, chances of success may be enhanced for external reasons that we cannot take credit for. Knowing this has a great liberating effect, since we are longer attached to the results of our actions. We can afford to look upon the consequences of our decisions with calm, analytical reflection and strategise to avoid missteps in the future. However, if we are deeply attached to the consequences of our decisions, then we almost inevitably become inhibited about taking decisions in the first place. The paralysing fear of failure or equally the breathless anticipation of success begins to cloud our judgement. It is far more likely that in any given situation one is able to take the most appropriate decision, if the process could be detached from such inhibitions or expectations. This is the message of the Bhagavad Gita as well.

Zen goes further and accords a very high value to intuitive and inspirational factors. While enhanced concentration improves the chances of effective decision-making, it is that sudden intuitive leap of imagination which may deliver inspirational success. We catch a glimmer of this in several success stories. Zen trains the human mind to go beyond rationality, beyond logical reasoning, that often misses and sometimes even distorts the total picture. It arouses the innate power of the human mind to transcend limitations of thought and leap into a sudden and complete awareness. This is what Zen practitioners refer to as ‘satori.’

We all have sudden flashes of brilliance, a momentary and blinding dispelling of ignorance, an unexpected bolt-from-the blue awareness of things as they really are. We sometimes discern such insights in poets and philosophers and not necessarily from the mystical East. Here is my favourite part from Wordsworth’s ‘Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey’ which have a distinct flavour of Zen:

And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man;

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things.

The culmination of rigorous Zen practice seeks to make this fleeting awareness a permanent condition, an enduring perspective.

Yamada Roshi lived his own teachings, by running a very successful healthcare institution even while being a preceptor to hundreds of disciples who came to be educated at his quaint little zendo at Kamakura outside Tokyo. He died not long after I returned from Tokyo in 1989, leaving behind many grateful disciples. I still cherish my encounter with him which he insisted was no coincidence. I would hope that our encounter today, here and now, is also not a coincidence, but something deeper bringing us together. That is what he would have said, with a confident smile on his gentle face.

___

This was a talk delivered at the India Habitat Centre on July 27, 2013.