Cinema is a collective achievement arising out of the negotiated interactions between the producer, consumer and the filmic text. The understanding of the filmic text is headed in two ways. On the one hand, cinema can be understood as a sequence of events and spectacles that form the narrative. On the other hand, it is a monitor to our personal life and its meaning is free to be shaped and warped by individual experiences. But every action performed by the actor is manipulated and his actions are completely controlled by the director. Its effect upon the spectator may be hidden, partially revealed, or, fully revealed by the performer. The subjective camera allows the spectator to experience this manipulation by the performer, which, in fact, is the input, and the effects that the spectator envisages is the output of these manipulations which enrich the spectators and force them to engage with the film as a medium. Through an in-depth study of P. Bharathiraja’s Bommalattam (2008), the article explores how popular cinema, a vehicle of entertainment, creates and deconstructs the spectator’s experience of viewing a filmic text as a metacinematic metaphor through which are raised the issues of spectatorship and the problems inherent in the creation of filmmaking.

Introduction

An image is a chain of representations carrying inherent meanings which flow from the producer to the consumer. In the essay titled 'The Film Sense', Sergei Eisenstein claims that the task of the film maker is to ‘transform the image into a few basic partial representations which, in their combination and juxtaposition, shall evoke in the consciousness and feelings of the spectator…that same general image which originally hovered before the creative artist (1957:33).' The image, according to Eisenstein, is not fixed or readymade. It is envisaged by the artist and created by the spectator. The spectator, then, is engaged in the process of construction from the series of representations to derive the meaning of the image. The foundational metaphor of the disembodied eye integrates into the body of the text and erases the distinction between the producer and consumer to arrive at the core of the text.

Tamil film director Bharathiraja’s Bommalattam is a self-reflexive film that centres on the question, ‘How do we know if the things we perceive are real or just an illusion?’ The film is an attack on filmmaking which taunts the eyes of the spectator. It explores the psyche of the actors as well as fabricates a self-consciousness towards film acting and film making. The film also raises the question, ‘How do we know that our thoughts are not being manipulated and our perceptions of reality are accurate?’

The film oscillates between the ideas of whether the cinematic world is real or merely an illusion of the spectator. The cinema audience is taken on a roller-coaster ride into a simulated world filled with mystery, murder and masquerade. A large part of the narrative takes place inside the world created by the meta-cinema Cinema, which is not aware of the audience or of the characters in the movie till the film reaches its climax. This world is something that could be called the interface of the real, a passage where codes are instantiated into streams of information and communication travels at the speed of light. Basically what is visible in this film is not possible to see with the eye alone (Rossak 2008). The special effects and the suspense of the film evoke the feeling of being inside the world of Cinema.

As the title of the movie suggests Bommalattam is a Tamil outdoor entertainment meaning ‘puppet on string’ (Anantha 2013), where bommai means doll and attam means dance. It combines the techniques of both the rod and string puppets where the puppeteer hides behind the screen and manipulates the puppets. Similarly, the spectator and the actors are mere puppets in the hands of the director which is evidenced through the Cinema of Rana. Rana himself says that ‘cinema is a bommalattam and the actors are mere puppets in the hand of the director. We have to show what is not there.' The story revolves around the director Rana (Nana Patekar), the heroine Trishna (Rukmini Vijayakumar) and the CBI officer Vivek (Arjun). The film also dwells on recurring motifs such as the camera’s way of presenting the watchful eyes of the director, his unusual gender construction, the mode of flashback to divert the audience’s attention, as well as the film within the film which creates suspense in the eyes of the spectator. It alludes to the fact that one can never be sure whether what they are experiencing is a dream or reality. This essay attempts to reach a possible conclusion for these questions by deconstructing the spectator theory through meta-cinema.

The spectator in and out of the text: an analysis of Bommalattam

The formal features of a filmic image—the framing of shots, the repetition of set ups, montage, the props, the position of the characters and the direction of their glances can be taken as a complex structure and understood as a characteristic answer to the rhetorical problem of telling a story and showing an action to the spectator. The significant aspect of these features is that they have to do with seeing. The seeing involves both the characters’ way of seeing each other and the way those relations are shown to the spectator because their complexity and coherence can be considered a matter of point of view. The object of this study is to read Bharathiraja’s Bommalattam as the ‘specular text’ (Browne 1996) which is an allegory of creation.

Rana, the protagonist, acts as an alter ego for the director, Bharathiraja himself. This is because a director’s experience of direction forms the basis of his narratives. William Hope in Italian Cinema: New Directions says that ‘the exposure of film-making practice undermines the illusion of any direct contact between the spectator and the extra-filmic life of the director (2005:38).' The film begins with a sequence of shots which leads the spectator to many exegeses. The diegetic sound followed by the image of the director’s chair is usually identified with filmmaking. The history and design of the director’s chair go back to hundreds of years, with its roots being definitely traced to the 1400s. The director is the driving force of a film, who establishes a direct relationship between a written narrative and visual representation. He is responsible for overseeing the creative aspects of a film. His decision seems to be final in the making of the film. This is very much evidenced by the opening scene of Bommalattam when Rana (Nana Patekar) changes his heroine because he finds her to be unprofessional. He has a control over the content and flow of the film’s plot, selecting the locations where the film will be shot and in managing the technical details of the film such as the positioning of the cameras, the use of lighting, timing and the content of the film’s soundtrack. The director’s chair with drops of blood leads to various connotations for the spectator: the implication is that either the director is trying to visualize a thriller or a suspense movie, or the director himself is the killer in the plot.

At the very outset of the film the spectator is exposed to two directors: Bharathiraja and Rana. The film within the film, titled Cinema, is about the mysterious happening in the film industry and the hardships faced by the director in the making of a movie. Even though Rana is eccentric and unpredictable, he is an award-winning director whose films have an aesthetic appeal among the elite audience. He is a perfectionist but his personal life is in shambles as his nagging wife always suspects his fidelity. Rana acts as the spectator inside the film for the audience, as well as the meta-director.

The true identity of the heroine has been a subject of much talk in the media. But why are people curious about a heroine’s face? Why does Rana hide the identity of the heroine? Neither her name, nor the identity of the heroine, finds a place in the media and the movie posters. Is the identity of the heroine a requisite factor for the audience to come to the theatre to watch the film? Does it raise any question regarding to Laura Mulvey’s male gaze that women are the objects of men’s pleasure? Laura Mulvey’s 'Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema' (1975) privileges the male gaze in mainstream cinema which sets up the male protagonist as the active figure in the narrative; It is through this character’s view point that the audience watches the film. In Bommalattam, Rana the male protagonist/filmmaker is responsible for the creation of the male gaze. But his gaze is not directed against the active/male or passive/female. Instead his gaze is the force that drives the narrative. All these questions are raised when one watches the film for the first time.

The day when Rana is going to introduce the heroine in front of the media before the film’s release, his call with the producer is overheard by the media and he is shown to have an illicit relationship with her. Besides his conversation with the heroine —'I created you and I am going to destroy you’—triggers questions in the mind of the audience. It implies that either he might kill the heroine, or it alludes to the authority the director has over his heroine. By the time the media gathers at the hotel, Rana manages to escape with his heroine. He finally kills Trishna by creating an accident-like situation. Rana escapes with minor injuries and Trishna dies. The audience is exposed to the truth that it is Rana who pulls the car over the cliff. But the characters in the film are unaware of it.

The rest of the story is told in flashbacks. Why had he killed his heroine? What was his relationship with her? Is Rana behind the mysterious murders on his sets? Will Vivek be able to nab him with conclusive proof? All these questions create in the mind of the audience the belief that Rana is the suspect. When the film opens, the audience is active with the spectator but as the film progresses he becomes passive and this passivity is what turns the spectator into a mere object of the cinematic gaze.

The film spectator constitutes a resonating body and the illusion-forming medium of the cinema. The formation of illusion versus reality in the spectator body, emphasizes the relevance and interpretation of the spectator experience of the filmic text. The events on the screen and the spectator are considered individually or as isolated entities; if one needs to enlarge the frame of description, the relationship between the spectator, the events on the primary screen and the characters become more visible. Only this will enhance the aesthetic experience of the film. The triangular relationship— spectator-Rana-Arjun will become theoretically envisioned through the spectator theory of filmic experience. Keeping this in mind, if one analyses the film Bommalattam through the spectator theory of cinematic experience, all these questions will find tenable resolutions.

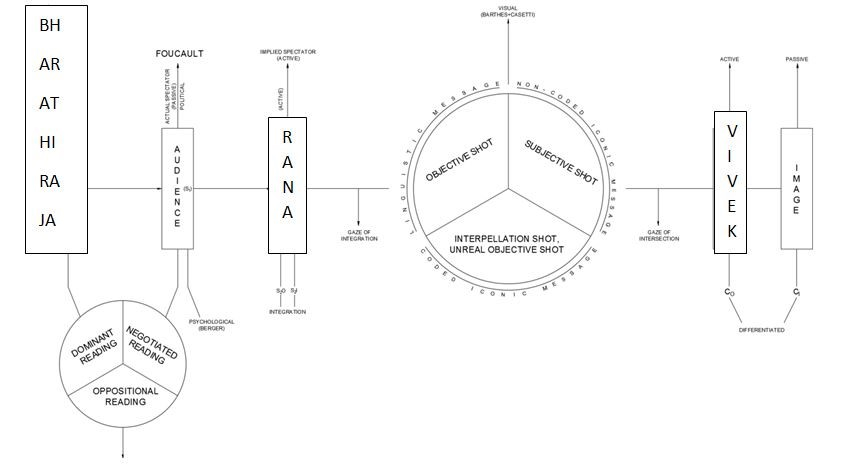

From the above model, Bharathiraja is the director Rana (Director), the (implied) spectator as insider, and Vivek, the co-star of Rana. When the film begins, we, the audience, are controlled by Bharathiraja. But as the plot progresses the audience is completely controlled by Rana the director, who is the spectator inside the film; the audience visualizes the meta-cinema Cinema through the eyes of Rana. The gaze of the spectator is the gaze of Rana. The method of analysis used in this paper conjoins the audience theory with a semiotic analysis of filmic text, where the spectator’s eye becomes the gaze of the camera or the ‘I’ of the camera as William Rothman (2004) puts it. In order to make more explicit what the model precisely means, the entire process is described in a linear scheme.

Bommalattam opens with the shooting of Rana’s new film Cinema. The audience reception exerts a Foucauldian power over the director-audience. He is active and his understanding of the story can be configured using Stuart Hall’s three types of reading a filmic text, where he places the audience at the centre of the image (1980). The audiences are free to decode the meaning of Bommalattam. For the audience, the sequences of Rana and the co-stars are easily comprehensible because they visualise the filmic text without any mediators and create a hermeneutic space that empowers them to accept or reject the producer’s message.

According to Hall, the audience is active because they interpret and respond to media texts differently and actively engage with the messages. They are free in decoding the media text. Hence, the reading of Hall falls under three major categories depending on the relationship between the text and the audience. In preferred reading, the receiver accepts the producer’s text fully. Hence, the code seems natural and transparent. The negotiated reading is the point where the reader partly believes and accepts the code. He then modifies the code based on his/her experiences and interests. In the oppositional reading a compromise occurs between the preferred and negotiated reading and the reader completely rejects the message that the sender wishes to convey. As the model progresses, we reach the spectator’s cognitive process of understanding the image and the different ways of seeing an image through the medium of gaze, which acts both as an integration and intersection. The whole process could be understood by citing examples from the film. How the spectator reaches the meaning is explained through the theories of Barthes (1977) and Casetti (1999). In order to understand the process first, we have to get know how both the theories complement each other.

The establishing scene is a long shot where the sequence of images viewed by the spectator teaches him that it is a film set. The audience is only a witness in this shot, and the linguistic message provided by the director’s chair with the caption ‘DIRECTOR’ points to the fact that Bommalattam is about the making of a film. This is an objective shot where the spectator is placed in the position of a witness and s/he derives the meaning from the linguistic message conveyed in the film. In this way, the subjective shot and the linguistic message are linked together. The unreal objective shot can be linked with the flashback modes which are full of suspense.

The spectator is aware that there are unforeseen scenes in the film. For instance, the two murders during the shooting of his film, puts the finger of suspicion on Rana. Here the camera acts as the signifier for the spectator. The audience does not derive the message directly from the film but from the thoughts of Rana. Thus, the unreal objective shot and the coded iconic are linked together. In the interpellation shot the voice over of Rana is directed towards the audience. The audience interpellates with Rana to form the coded message of the film. When the village chief (Manivannan) constantly lusts over Trishna, Rana states in a rage that he would kill the village chief because he suspects that the chief would cause him more inconvenience. The next day the chief is murdered and the audience comes to the conclusion that Rana might be the killer. In the subjective shot, the audience, as well as Rana, learns the truth from Trishna. Here the audience and spectator form a direct link with the other characters and the truth is revealed.

Yet as the film progresses, the lines between reality and illusion begin to blur more and more until we get to the final scene in which truth and fiction are completely indistinguishable. It seems to be both real and an illusion at the same time. This distinction creates a difference in the perception of gaze as well. The areas where the gaze becomes integration and intersection, change the spectator’s experience of the distinction between illusion and reality. The audience experiences the gaze of integration when it provides a smooth insertion into the field of the visible. This is because the gaze of the audience is inserted within the filmic text and neither Rana nor Vivek is aware of this. This gaze is paradoxically an absence. But this gaze becomes visible when the spectator identifies with the characters. Hence the audience is not just an objective onlooker but is always involved in what he or she sees. For instance, the scene in which Rana pulls the car over the cliff, the audience’s gaze is absent in front of him. But in reality, he is viewing the events as a living presence.

The gaze becomes the gaze of the intersection when the spectators’ gaze merges with and intersects each other. Here, Rana experiences the gaze of intersection when a collision occurs between the gaze of the audience and that of Rana’s. This would provide the audience a complete experience of the film. At this point, the presence and absence of the gaze merge into the same film. They then separate in order to reveal what occurred while they collided with each other and hence the resultant becomes the real gaze. An instance for this is the final scene of the movie where the audience comes to know the truth that Trishna is not female, but male. When Rana’s truth is revealed by Vivek to the audience (whose gaze is absent) it collides with the spectator’s gaze and thereby forces the spectator to experience what is hidden in Trishna. Yet another example of this is the scene in which Babu (Trishna) reveals the secret that he was the murderer. Hence the object (Trishna) and the image get differentiated in the cinematic experience and the spectator receives the constructed or real image of the film.

Deconstructing the spectator theory through the metacinema Cinema

In Film Spectatorship and the Institution of Fiction (1995), Murray-Smith mounts an argument against the influential theories of cinema that characterize the spectator ‘as a dreamer or the dupe of an illusion’. (Allen 1998a). Allen replies to Murray in his article Film Spectatorship: A Reply to Murray where he quotes from his essay Representation, Illusion and Cinema (1993) that the spectator entertains mistaken beliefs about the image. He further states that the film spectator is not duped by the cinematic apparatus or forms of narration in the cinema; the spectator is fully aware that what is seen is only a film (21). But director Bharathiraja’s Bommalattam is different from this argument because the spectator sees the film through the eyes of the meta-director Rana without holding a mistaken belief about what he sees. The film, in which Rana plays the role of a director, examines the illusory realism of cinema and the techniques that lead to the formation of identification.

Though the film, Bommalattam, is about the act of filmmaking, the film does not unveil much of the techniques involved. Instead, it employs the meta-cinematic technique to blur the eyes of the spectator by creating an unusual gender construction. But, how far is the film-within-the-film relevant in Bharathiraja’s Bommalattam? How does it deconstruct the spectator theory? Why does the definition of meta-cinema not match with the academic definition? Rana’s Cinema tries to substantiate it. In the article Meta-cinematic Cultism: Between High and Low Culture, William C. Siska claims that ‘meta-cinema is practice that evinces the essence and structure of the film proper and not the subject or the story: the production and the reception of apparatuses are shown in the films in order to break the audience's empathy with the characters and the action’ (Chinita 2016). According to Kiyoshi Takeda (1987), ‘meta-cinema is a radical and experimental filmic category which stresses the materiality of the film rather than an immersion in the story’ (89). Both the theoreticians place the process of enunciation above its narrative result. On the other hand, meta-cinema may also refer to the conservative practice of making films about the industry (Chinita 2016). In the broad scenario, we can say meta-cinema opens a way for the directors to show their artistic proclivities and the nature of their engagement in the activity. It is an authorial discourse that forms the main story of the film and provides the cinematic techniques of film making and film viewing.

Rana’s Cinema is a matrix because it is not about the art of film making nor does it create the illusion in the mind of the spectator that they are watching a work of art. Instead, the audience has been pulled into the world which blinds their eyes from the truth. Even though the film is a meta-cinema, much of the story is unveiled in the prime text. The film Bommalattam is an artificial reality created to thwart the spectator from seeing the actual reality. No matter what we think of the film as a work of art, it brings to mind, countless interpretations about the relation between reality and illusion. Hence, what makes the film more relevant to a discussion is its ability to deceive the spectator. Films are composed of frames of images and actions which run through a machine at a certain speed to create the illusion of actuality. Engrossed in this deception, the spectator forgets that it is a film and comes to accept the fact that it is a reality. The relationship between cinema and experience demonstrates to the spectator that the filmic narrative is constructed as a game on which they are mere puppets in the hands of the director.

The principal metaphor in the film Bommalattam is that reality is not what it seemed to be. We should think of Bommalattam as a cinematic experience capable of demonstrating the relationship between illusion and reality on a sophisticated level such as whether it is possible for a director to deceive the audience by hiding the truth behind the camera. The film creates the belief that what people perceive to be the reality is an illusion or dream world. When Vivek reveals to Anitha (Kajal Agarwal) the complications that exist in the investigation that the burnt body in the car belongs to a man and not a woman, it again surprises the audience that what is seen in front of their eyes is a fake technique used by the cinema.

The spectator and the CBI officer Vivek, are in the same position. Vivek discovers reality not by assuming all is well just like the spectator does. Instead, he finds out the truth by learning that something is inside Rana by listening to the signs given to him by the latter. Thus, by investigating and not just accepting things as they are, Vivek discovers the reality. But the spectator is kept aloof from it till Vivek finds out the truth that Trishna is not a girl, but a boy. Thus the meta-cinema is just an illusion for creating suspense and deceiving the audience. By attempting to break down the viewer's confidence, the director becomes a master narrator of the film because there is always a relationship between the object and what goes on in the mind which the audience forgets.

Conclusion

The spectator theory of film adopts a structuralist approach wherein the meaning is constructed and controlled within the structure of the film. But the centre of this structure, the director, exists both within the structure and without it. The director inside the film text deconstructs the film through the structuralist text of the director outside the filmic text. By making the cinematic process a visible one, the viewer directly involves himself in decoding the signs and becomes aware of the myriads of nuances that they underwent beyond their perception.

Through Bommalattam, the very medium of film problematises the relation between the illusion of image and the reality of the world behind the screens. The film makers are in charge of this illusion and we experience this alternative reality by realizing the truth that we should wake up from a dream world created by cameras because it is this dream world that keeps us in the dark. By deconstructing the spectator through the meta-cinema, the film becomes a critique of the reception theory of Stuart Hall (1980).

Though the audience is free in deciphering the meaning of the film, Bommalattam defends the reception theory by proving that film makers have the power to choose what viewers get to see and what they don’t. Film makers challenge the viewers to question the reality within the film and cause them to redefine the viewed image and their identification with it. In Bommalattam, the author of the text (Rana) is inside the structure of the text itself. Though he is the centre of the text, he is also located outside the structure of the text (Cinema). The text is outside the meta-cinema and the truth of things is hidden from the outside world. By the same logic, the reality of the film remains hidden from the outside, because it is essentially inside the text.

References

Allen, Richard (1993). 'Representation, Illusion and the Cinema'. Cinema Journal, 32(2), 21-48.

Allen, Richard (1995). Projecting Illusion: Film Spectatorship and the Impression of Reality. NY: Cambridge UP. Print.

Allen, Richard. 1998. ‘Film Spectatorship: A Reply to Murray Smith.’ The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 56(1): 61–3. (Online at www.jstor.org/stable/431951)

Anantha, 2013. ‘Bommalattam: Puppet on String.’ Online at https://ananthablahblah.wordpress.com/2013/07/28/bommalattam-puppets-on-string/ (posted on July 28, 2013)

Barthes, Roland and Stephen Heath, 1977. Image, Music, Text. London: Fontana.

Bommalattam, 2008. Dir. Bharathiraja. P. Perf. Nana Patekar, Rukmini, Arjun. Therkathi Kalaikoodam.

Browne, Nicke. 1996. ‘The Spectator-in-the-text: The Rhetoric of Stagecoach.’ In The Communication Theory reader, edited by Paul Cobley. London: Routledge, 1996. pp. 333- 50.

Casetti, Francesco. 1999. Inside the Gaze: The Fiction and its Spectator. Bloomington: Indiana UP, Print.

Chinita, Fatima. 2016. Meta-cinematic Cultism: Between High and Low Culture. Academia. pp 28-40.

Eisenstein, Sergei.1957. The Film Sense. New York: Meridian Books, Print.

Hall, Stuart.1980. ‘Encoding and Decoding’. in The Cultural Studies Reader, edited by Simon During. 128-38 London: Hutchinson.

Hope, William. 2005. Italian Cinema: New Directions. NY: Peter Lang. Print.

McGowan, Todd. 2007. The Real Gaze: Film Theory AfterLacan. Albany: SUNY Press. Print.

Rossak, Eivind. 2008. The Still/Moving Image: Cinema and the Arts. Oslo: Unipub, Pdf.

Rothman, William. 2004. The “I” of the Camera: Essays in Film Criticism, History and Aesthetics. UK: Cambridge.Print. Online at https://showfiredisplays.com/directors-chairs/history-directors-chairs/

Takeda, Kiyoshi. ‘Le Cińema autorefluxif: quelques problems methodologiques’ in Iconics, Nikon University Tokyo, The Japanese Society of Image Arts and Sciences, 1987: 83-97.

Smith, Murray (1995). 'Film Spectatorship and the Institution of Fiction'. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 53(2), 113-127.