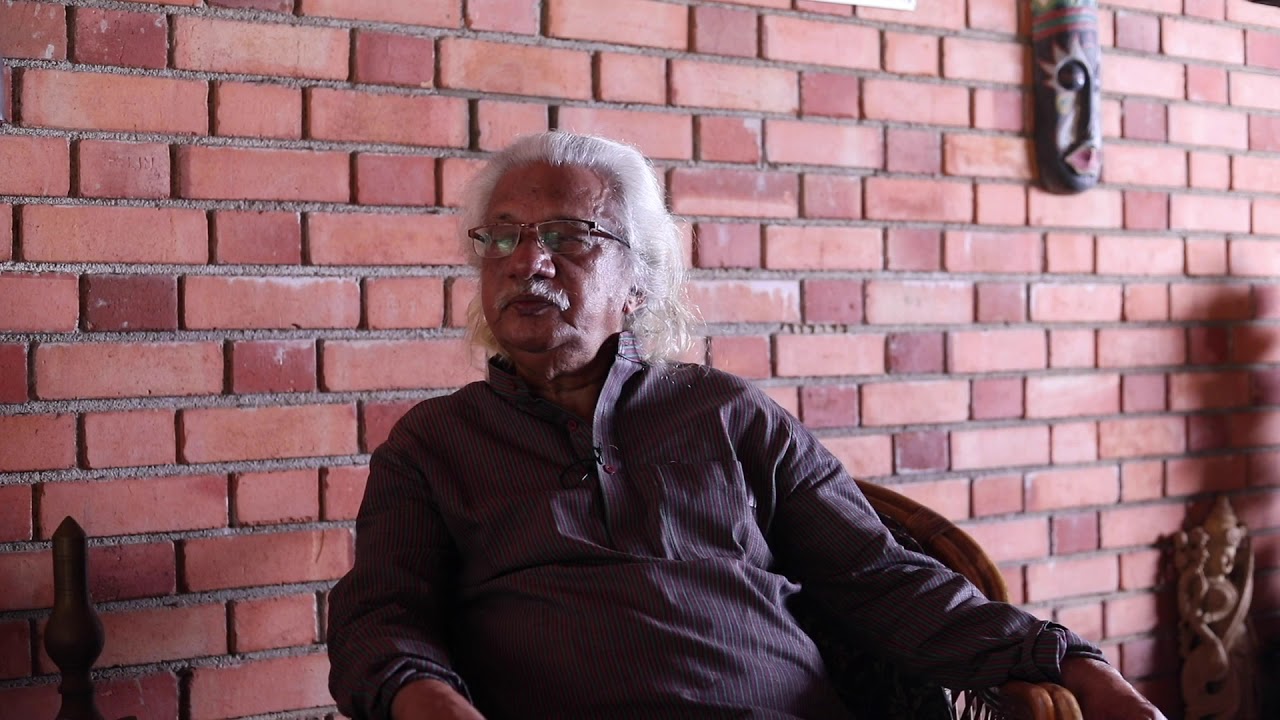

Adoor Gopalakrishnan is one of the most prominent auteurs of Indian cinema, and in a filmmaking career spanning almost half a century, he has created a body of cinematic work of great aesthetic quality and narrative vigour. His oeuvre comprises of 12 full-length feature films and a number of documentaries on arts and culture. He has also penned several scholarly articles and analytical books on cinema. He is one of the most internationally acclaimed contemporary Indian filmmakers, as is evident from the critical attention his films and retrospectives generate in film festivals across the world.

Adoor made his entry into films in the early ‘70s when the ‘new wave’ was lapping the shores of the country. A frisson nouveau was in the air, and various filmmakers in different languages were making films that were to change the very look and feel of Indian cinema. His films challenged the existing cinematic idiom and language to create a new visual sensibility and intense narrative style.

Born in 1941 in Pallickal, near Adoor in South Kerala, his early interests were literature and theatre. He wrote and directed plays, and was employed with National Sample Survey before he joined the Film & Television Institute of India, Pune. After graduating from the institute, Adoor came back to Kerala, and along with other cineastes in Thiruvananthapuram, formed the first film society in the state. The Chithralekha Film Society organised regular film screenings and discussions about films. He was also the driving force behind organising the first international film festival in Kerala, as part of a literary event.

His made his debut film Swayamvaram (One’s Own Choice) in 1972, which received critical acclaim and won several awards at the national level. Swayamvaram was about a couple, Viswanathan and Sita, migrating to the city in search of a new life of their own choice and liking, whose dreams are shattered by the harsh reality of life. His next film Kodiyettam (The Ascent) was about a village drifter’s coming to terms with life and its responsibilities. His next film Elippathayam (Rat Trap, 1981), also his first film in colour, was about the inexorable decay of the feudal system, and the exploitative relationships that it forces upon people. Mukhamukham (Face to Face, 1984) was one of the most controversial among his films as it was a searing critique about the decline of Communist movement in Kerala. It was about a peoples’ movement turning into a mere political party of power mongers, and the leadership betraying the hopes and dreams of its followers.

His next two films were based on literary works. Mathilukal (Walls, 1989) is based on the story of celebrated writer Vaikom Muhammed Basheer, and is an exploration into the mind of a writer. It is also an extraordinary love story, where the man and the woman never meet. Imprisoned in the male and female wards of the prison they are separated by a huge wall between them. Vidheyan (The Servile, 1993) was based on a Paul Zachariah novella, and was a dark, clinical examination of master–slave relationship in all its visceral complexity. It is about Patelar, the authoritarian landlord, and Thommi, his servile vassal, who form the inevitable dyad that makes any kind of slavery possible.

Kathapurushan (The Man of the Story, 1995) is the most autobiographical of Adoor’s films, and it takes a panoramic look at the various turning points in the history of Kerala through the eyes of the protagonist, who is an aspiring writer and thinker. Other films like Anantaram (1987) and Nizhalkkuthu (2002) look at life and society from various angles, probing deeper and extensively into the various conditions in which human beings find themselves.

His next two films were again drew from literature. They include Nalu Pennungal and Oru Pennum Randanum (2007), both anthology films based on the stories of Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai that looked at different aspects of femininity and female sexuality. Set in the middle decades of the last century, these stories delineate womanhood in all its avatars: you find here the sacrificing, self-effacing women, the belligerent and vivacious ones, and also the erotic and enticing enchantresses. His next work Pinneyum is a chilling film on the economy of greed that is swallowing contemporary society, where one is ready to sell even one’s identity to earn money.

Another remarkable character that distinguishes Adoor Gopalakrishnan as a filmmaker is his relentless efforts to promote serious, art cinema in Kerala and India, against all odds.

An auteur par excellence, his films are marked by their thematic variety, aesthetic charm and distinct narrative style. Adoor’s films chronicle and map the history of Kerala from the inside. In a way, all his films are autobiographical and deal with different periods in the history of Kerala and about different aspects of Kerala society, politics and life. They deal with human conditions at the most elemental level, and coupled with keen observation and intense sensibility about the ‘local’, his films have always had a universal appeal.

C.S. Venkiteswaran

Following is a translated and edited version of the video conversation with Adoor Gopalakrishnan conducted by C.S. Venkiteswaran on March 07, 2020 in Thiruvananthapuram.

C.S. Venkiteswaran (CSV): At that time, when you were studying at the Pune Film Institute, the institute was quite young, and its graduates were just entering the industry. Also, there were not many options before them then. The only two choices were either opt to become an assistant director or get into some government establishment, like the Films Division. This being the case, how did your decision to stand independently come about? What were the options you had then?

Adoor Gopalakrishnan (AG): When I reached my final year, I decided that come what may, I would not go to Bombay. I felt that there was no one from the industry I wanted to assist because then it meant I would have to unlearn whatever I knew and had learned by then.

So, together with a few of my batchmates from various departments I formed a unit. Devadas for sound, Latheef for the camera (later he left the field altogether), Melattoor Ravi Varma for editing, Bhaskaran Nair for PR work and I, for direction and scripting.

CSV: This was in Pune or Kerala?

AG: This happened when I was in my second year in Pune. The idea was that after completing our third year, we would go back to Thiruvananthapuram and work together as a technical unit. We prepared an elaborate manifesto. The first point was that we would start film societies, starting from Thiruvananthapuram and then spreading all over Kerala, as a movement itself. Secondly, publish good literature on cinema to disseminate knowledge about it among people. And lastly, we would get into production and distribution. So, it was sort of a three-pronged approach that we prepared.

So, with this manifesto we landed in Thiruvananthapuram. Firstly, we started the film society. We didn’t have money to produce films. But if you registered your organisation as an industrial cooperative, the government would give you ten times the share of the money you invested. This might sound like a huge amount, but our share was only ₹100 back then! We were about 20 or 25 members, having pulled in our friends and relatives as well.

CSV: Chitralekha…

AG: Yes, there were two things that we started. One was the film society and the other was a cooperative.

CSV: Both in 1965?

AG: Yes, both were started in ’65. Those days I worked day and night with the film society—sourcing films, bringing them here and screening them. I was the operator too; we had a 60mm projector. After some time, we got permission to install a 35mm projector at the Tagore Theatre. I used to operate that too!

We did all our productions in the name of our film cooperative. It was hard to make documentaries back then as there were no funds or grants for them. With extreme difficulty, exercising Bhaskaran Nair’s influence with the government offices, we got funds for making a documentary—And Man created—on handicrafts. Our budget was like ₹ 6000–7000. There are many stories behind the making of this documentary, and it was well appreciated.

Around this time, Jean (Jehangir) Bhownagary happened to see my film Great Day. He was an Indo-French officer who made historic contributions to the Films Division. He saw the film. I was the first one from the institute who caught his eye. I didn’t know this had happened. He instructed his officers to make me part of the panel and get me to make films for the Films Division. That’s how I made the documentary Towards National STD. Afterwards there were other documentaries. They all came out under the banner of Chitralekha.

After we passed out of the institute in ’65 and came here, the only thing that was happening was these documentaries. We didn’t get anything here in Thiruvananthapuram. Once in blue moon, some departments, like the Family Planning department, would float the idea of making films (documentaries). For that there would be several competitors, most of whom would have no idea of the topic. Anyone can make a documentary, right! No need of any specialised knowledge or anything!

I made this 20-minute-long film called Mantharikal. After that, I made an hour-long documentary called Pratisandhi on family planning. It had all the elements of a commercial cinema, like songs and everything.

Ultimately, the cooperative became a liability for me. We had so many expenses—from rent to salaries of its staff. To keep it going, one needed to get work constantly. So, we were occupied with making documentaries or other things that came our way, regardless of the topic.

CSV: The film societies mushroomed all over Kerala. At the same time, you also initiated film festivals. Could you share your film festival experiences?

AG: The fifth All India Writers Conference happened between December 1965 and January 1966. The main people behind it were M. Govindan, M.K.K. Nair and C.N. Sreekanthan Nair. Being the first ever All India Writers’ Conference held in Kerala, they wanted to scale it up. Thus they planned for the conference enthusiastically. When I would come home for vacations, I usually met Sreekanthan Nair, Govindan and others. During such meetings, I would speak to them about cinema. One day, Govindan asked me—why not hold a film festival too in parallel with the writers’ conference? Without any thought, I readily said yes. At that point, the Chitralekha film society was about six months old, and by then I knew where to source films from. It was certainly an unwanted confidence, but I agreed anyway.

Only two Indian filmmakers participated—Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak. The rest of the films were important films like Mikhail Kalatozov’s The Cranes are Flying. Its distribution rights in India was with Guru Dutt. I wrote to him and he gave permission readily and for free. Thus, I sourced 21 films like that. The important fact was that these films were screened simultaneously across 10 centres in Kerala during the one-week-long festival. This was a huge deal! A film festival in all of Kerala! Also, such films, outstanding films that were never seen before here, were screened.

CSV: How did Swayamvaram (Adoor’s first feature film) come about?

AG: Before I did Swayamvaram, a lot of time passed without doing any meaningful work. Even my own people were getting frustrated, and were asking me to do something. Frustration was growing within me too.

I had given myself five years when I returned from the institute. Not that I was doing nothing, I was doing something or the other. During this period, I did all kinds of technical work related to cinema—from camera work, sound recording, editing to even projection! I gained a thorough working knowledge about the technical side of cinema.

Before Swayamvaram, we approached C.N. Sreekandan Nair for an NFDC (National Film Development Cooperation of India) project. He was an established writer, and had also written a few film scripts. So we asked him to write a script for us, and he did. It was titled Kamuki (Sweetheart). We sent it to NFDC for a loan. No, no, it was FFC (Film Finance Corporation) back then. They rejected it; they didn’t sanction the loan. I did meet its MD in Bombay and asked why the script got rejected. His response was, ‘India faces so many issues now, and you want to make a love story? Cinema has to contribute towards India’s reconstruction.’ I said, ‘How can I alone do any reconstruction…?’

Then I decided to write a script myself. That’s Swayamvaram. The FFC gave us a loan of ₹1.5 lakh. Together with the money we had earned through our documentaries, we made Swayamvaram. So ₹1.5 lakh from the loan (the interest was 18%), and we put in ₹1 lakh—so it was a total budget of ₹2.5 lakh.

CSV: So how did you manage such a huge cast with this budget? Because they were all superstars of the time.

AG: Our budget allowed us to give around ₹10,000 for an artist. Sharada (the heroine) was a top star in those days. When we contacted her, she agreed but demanded a sum of 25,000. From where would we find 25,000? Finally, we managed it, cutting down my own remuneration.

But performance-wise, the presence of Sharada and Madhu took it to another level. In the beginning I wanted to cast some fresh faces. I did a lot of searching for that. But girls from good families would not come to work in films. Even if they were willing, their families would not allow them. Because generally the film industry was not seen in a good light then. That’s why we had to look for actors from other states. While for Madhu, I had known him from the time he was in School of Drama, and I don’t even remember if we paid him at all. So meagre was our budget!

CSV: This film deviated from the standard template of films at the time. There were no songs. Also, this film was different in the way the shots were taken, the length of the shots, the way it handled the premise, etc.

AG: Yes, everything was different. When Swayamvaram was released in theatres, we had managers from several theatres calling up and saying, ‘Very good story, why didn’t you add some songs too?’ A film distributor had agreed to distribute it initially, but he backed out at the last minute. Then, we set up a distribution company, recruited and trained people and sent them for distribution.

For me, Swayamvaram is all about one’s own choice. It is the choice of which way one should go. It is a crucial choice. The film has so many layers. It is not mere storytelling. One, it’s about an intense love between a woman and a man. According to the norms of our land, they have to get married to live together. One advantage of a marriage is, in our society, marriage is not just happening between two individuals but rather two families. The families are there for the couple—for support, advice and help. In the film, there is no hint of the couple’s background. A man and a woman. No clue about where they’re from, where they studied or how they met. Such details are not relevant. Such a couple is coming to an unfamiliar, small city—Thiruvananthapuram. What does the society prevalent then, or maybe the present society even, has to offer them? This is what the film’s about. For them, it’s a journey from their dreams to a reality, a journey from hopes to shattering of those hopes… Their love for each other is important because both of them are scared of losing each other. There’s this episode which is repeated thrice in the beginning of the film—of them playing around, the sort you would see in a typical commercial movie, lovers prancing around. This episode is an imitation of that, even the posters of movies are used.

CSV: Yes, also a scene from Chemmeen is imitated.

AG: Yes, those images are what we see as the symbols of a happy life. Then the descent starts and the soil underneath the feet starts to slip away. And they wake up to the reality.

The man believes in his ideals but even he has to compromise under the circumstances. After he loses his tutorial job, he has to work in a sawmill. He gets that job because the previous worker was thrown out. Our man could not react against the injustice because he needs that job. He avoids the ex-worker who follows him constantly. He is haunted by him. It is actually his own conscience—guilty conscience—that is haunting him.

One explanation I’ve given for the film is—the moral crisis of the middle class. In 1973, this film was the Indian entry at the Moscow Film Festival. One criticism of the film that appeared in their official bulletin was that the male lead is only passively watching political processions, why is he not joining them? But that is what is the film is about. They were unable to grasp it.

CSV: In the film, we see the couple (Viswanathan and Sita) coming to the city. First, they take a room in a hotel, and then they rent a house. So, it is a fall into reality. The man is an aspiring writer. He tries to make a career in that, but fails. Then he takes up different jobs, each job is like one step downwards in life. But Viswanathan and Sita face this crisis that emerges in their lives after they came to the city in their own different ways. It seems like Sita gradually gains strength while the man becomes weak. This theme is repeated in many of your films. But I think it started in Swayamvaram—the way man and woman face the challenges of life.

AG: Women are certainly stronger than men. Look at how things are in Kerala now. There are many households where men just don’t work but return home in the evening inebriated. The women work hard to run the house and raise the kids. All the man does is to create a ruckus and even beat up the wife. There are such families! Then there are men who desert their women, there are widows… These women don’t just sit around and sob. They face life with courage. That’s an important thing about Kerala. We don’t need to talk about women empowerment and all. Women here are strong. I grew up seeing that. So yeah, I certainly think men are weak.

CSV: The ending of Swayamvaram is quite enigmatic and widely discussed too.

AG: In the beginning Sita exerts her own choice when she comes to the city with Viswanathan. At the end again, she is faced with three choices. Maybe live like her neighbour Janaki Amma, who earns her living by pounding rice grains and selling it in the market. Or choose an easy life, maybe with someone like the smuggler who keeps a mistress in her neighbouring home. The final choice is to go back to her own home, and this is what most people advise her to do. When she goes for an interview, she is asked to pay up a deposit. Where will she find the money for that? She thinks of her choices. She is determined that she won’t go back to her home. How is she going to live? It is with this question that we end the film, with a closing shot of the woman’s face.

That is why the ending has disturbed people. That was the intention. We haven’t given a solution to the woman’s crisis. The open ending has left people asking about it even after so many years. What happened to her? Well, the film is throwing that question at you. What has the society kept in store for her? The film reflects our living conditions.

CSV: While Swayamvaram is about making choices, the next film Kodiyettam is entirely different. The protagonist, Shankarankutti, has no choices in front of him. He just floats in life! How did this theme come up?

AG: There are many such laidback characters in our villages. At the same time, they do have a lot of goodness in them. They expect nothing from life, and have nothing to prove. They are comfortably wedged in the easy flow of life. The character in Kodiyettam gets along very well with children. When they need him, they turn to him, but ignore him at other times. One time, after they had food, his friends leave him at a hotel alone to deal with the bill. ‘They’re good people. They only asked me for my shirt,’ this is what he says about the hotel management.

Many people think of him as a fool. But no, he is not a fool. He’s just an ordinary man who hasn’t even thought about his identity. For the woman he marries, there is no change in life when she comes to his place. For her it is just a shift from one kitchen to another. She cooks food for him, and he eats away happily. Once, after he finishes his plate, he goes on scraping it. Then the woman picks up the rice pot, scrapes at the bottom and says the rice is over. Then it hits him. He asks his wife, ‘Shantamma, you haven’t eaten, have you?’ It is his duty to feed her and take care of her. He is a simpleton, hence the question.

The film is conceived as a kind of spiral movement. First, he roams around on foot, then he goes around snuggled at the back of bullock cart, and then he is on a motor vehicle. He has always been obsessed with motor vehicles. So, when a car speeds past, splashing dirt on him, he can only say in amazement: ‘What speed!’ His wife says, ‘Your shirt is ruined, how will we go to the ceremony now?’ He dismisses her concern saying, ‘Oh, it is nothing, it can be washed off.’ People said—What a great philosophy! This isn’t philosophy or anything. He is just naturally reacting to a situation.

Later, he becomes an assistant to a lorry driver. Shankarankutti realises that whereas the driver is a big taskmaster, he has a secret life with a mistress from over the mountain pass whose chastity he constantly questions. Shankarankutti is not able to grasp and connect the happenings in his life, and, through his confusions, he evolves into a mature person.

CSV: One specialty of Kodiyettam is that you haven’t used any kind of background music. You have used only ambient sounds. What was behind this decision?

AG: The hero is someone who roams around with no aim or purpose. The problem with background music is that it accentuates emotions. I didn’t want that in this film, so, I decided not to use music.

Actually, while watching the film, most viewers were oblivious of the lack of a background score. For over three months, I travelled all over central Travancore with a voice recorder and captured several kinds of sounds. There are so many subtle sounds that we generally don’t notice. For example, noise that birds make early morning is different. At noon, even the crow cries in a different way. Once I saw a crow trying hard to imitate the singing of a cuckoo. I tried to record it but it flew away before I could. One afternoon, I was walking on a road, there were so many trees around, I saw a crow sitting on a branch. It was trying to imitate the singing of the cuckoo. The moment I took the mic, it flew away. It understood it was trapped! So yes, only when you take a keen interest in nature, you will understand that its sounds are different at different times of the day. The night birds—the sounds they make are different in different hours of the night. I have used their sounds for scenes that depict sleepless nights.

These sounds and songs of nature, they are a part of our life. We can use them to portray different states of life. People generally think music can be used in a film very easily. It is used to thrust emotions on a scene where there is none. For example, take a tragic scene, you play four violins and build the sadness. With overuse, using the same kind of music for the same kind of scenes, background score has become so predictable now.

CSV: In all your films, music is used very sparingly. Its use is very minimal. Why is it so?

AG: The music has meaning only when it’s used minimally. Mainly, I use theme music, like in Elippathayam. The music in that film is very special. My brief to M. B. Sreenivasan was that an impression should be created that it’s falling and falling and is never completed. After he composed it, Sreenivasan said, no one’s going to hum our background score! That is its uniqueness. But the score gets completed in the final scene when the man emerges from the pond. It is like a sentence that has begun in the first scene is being concluded in the final scene.

CSV: Your next film Elippathayam is special in so many ways. It was your first colour film, and is also a globally acclaimed film. It also marked the beginning of your association with General Pictures. A new, enlightened producer like Vinayachandran Nair entered the scene. Tell us something about this new association, and also about the theme of the film.

AG: In our life we encounter many situations to which we should naturally react. But most times we do not. Why? This was a question that haunted me for a long time then. Finally, when the answer came to me, it was a very simple answer. We don’t react because reactions often make matters inconvenient for us. The easier route is not to acknowledge the situation that warrants our response.

I wanted to take the example of one such extreme case. Where do I place the story? I chose the time period when our society was positioned right after the joint family setup, which was a part of the feudal system itself, had ended. Why wasn’t the land partitioned in the joint family system? Everyone in the family lives together under one roof. The property is not shared, it is taken care of by the family elder, the patriarch. His own children not important, as in the matrilineal system, the sister’s children are given prominence. The women don’t leave their house after marriage, the husbands come and live with them. This was the system which in time started slowly degenerating. Because many patriarchs started caring for their own children instead of their nephews. Legislations were brought about and the system started to change. One such feudal family at a time when feudalism had ended. The main support of feudalism was land and the agricultural revenue. The land got partitioned and each family became separate, a nuclear family. The film is about such a family, and about a person who was used to living in the feudalistic set up where he didn’t need to work, as others worked and the landowners reaped. Of course, feudalism had some good points too. The human relationships, bond with the land, bond between the landowners and the tenants— feudalism was full of special, complicated relationships. Anyway, when the system changed, it left behind only its burdens. The land and the revenue sources that helped feudalism flourish slowly started depleting.

In this particular family, Unni, the elder brother, is the family patriarch. He has an older sister, but she got married and moved out. Unni has two more sisters younger to him. Unni has all the flaws embedded in the feudal system. One particular thing is that, from the beginning to the end, at any time we never see Unni share his fears or joys or memories with anyone. Not even a little bit.

CSV: He is always engrossed in his own body.

AG: Yes, we always see him tending to his own body—be it cutting his nails, or applying oil, or plucking out grey hair. He is absorbed in himself. He is not concerned about the society, not even his own family members. He needs them only to take care of his needs. His sister tends to him day and night like a slave. When she is taken ill suddenly, the wheel stops turning for him. Thus emerges a terrible situation. I used that time period, such a character and such social circumstances for this film.

CSV: The use of colours in the film is also very interesting. The colours that you have used for each sister, I feel, are very important.

AG: Since it was my first colour film, I was determined that colours be used carefully. A wide variation in colour is not possible for women, especially in Kerala of those times. We could bring colour only in their upper clothing. Women wore white mundu in those times. Sari was slowly picking up with the new generation. Like the youngest sister wears a sari. So, for her, I chose different variations of red. The middle sister gets a blue colour. Blue denotes sublimity and also submissiveness at the same time. It is a cool colour. As for the eldest sister who lives separately, I chose a green colour, which symbolises earthiness and practicability. Thus, I gave each of these siblings a different colour. If you combine these three colours, you get white. In this white colour, I gave vertical lines. Vertical lines generate a sort of restlessness in our minds. Since they are siblings, they’re not totally different from each other. They do share common traits. So, these colours play out against the grey of the house—the grey that has lost its colour due to age. This is the backdrop against which the colour scheme works.

The script of Elippathayam was something that I finished very quickly because the story was brimming in me. It is about me, and about the people around me. All the characters are persons from my family, including my mother. I had a totally unremarkable uncle who did nothing in life. He never got married, and lived in the shade of my oldest uncle. I got the idea for Unni from this uncle. A sort of protopye. But I didn’t make my character just a carbon copy.

CSV: Anantaram has a two-part structure like Mukhamukham. But the difference is, in Mukhamukham, the viewers get only what others are thinking of the lead character. We have no clue what he himself is thinking or about him even. The narrative is pieced together from what others say about him. Anantaram is the polar opposite. We don’t know what others think of the character, but we get to know only what he is talking about himself.

AG: He is someone who is on the brink of a nervous breakdown. The stories that he tells are about how he got to this state. He tells us only two stories but there are many more stories. Each person carries the traits of an introvert and extrovert within him. When situations demand, the introvert emerges and then withdraws afterwards. This man too is the same. It’s about his experiences. It is a film about the process of creation.

CSV: What he experiences is a hallucination.

AG: He is trying to rationalise the irrational.

CSV: He is trying to create a narrative about himself, in different ways.

AG: That is the process of storytelling.

CSV: But he is not a storyteller.

AG: Exactly! He is just a sensitive young man.

CSV: In the film Mathilukal, the protagonist is a storyteller and that’s why he is able to recreate his experiences through imagination. He can transcend those experiences. He is able to detach himself from his own experiences and analyse them. Whereas Ajayan in Anantaram is able to present the world and life around him only from his own perspective. But Basheer in Mathilukal is able to detach himself—that’s what makes him an artist.

AG: He sees himself, his experiences and others around him as his characters. He creates the character of the woman for company. She might be his imagination, or might be real. Basheer (Vaikom Mohammed Basheer on whose story the film Mathilukal is based) had always insisted on the existence of such a female. But I kept her existence as a dual proposition, as a kind of compliment to the writer.

CSV: This is a very widely read story by Basheer. People would have had high expectations from a film based on such a story. How big a challenge was its making? Also, this was the first time you adapted a literary work for your film. So far, all your films were your own stories. How challenging was it and why did you choose this story?

AG: This story was published in the special edition of Kaumudi magazine in 1967. I read the story and called up M.T. Vasudevan Nair. Much later, when the film was done, I got to meet Basheer. He and his wife came early in the morning to the hotel where I was staying. When we met, his wife said that he was so excited that he didn’t sleep at all the previous night. See, how innocent and modest he was! He just laughed and didn’t deny it or anything. We spoke about several things that day.

In between, he asked me, ‘How does the film end? Does the hero come out of the jail holding a rose in his hand?’ I panicked a bit because that was not how the film ended. I replied in a low voice, ‘No.’ He didn’t say anything.

CSV: Coming to Vidheyan, your next film—it is based on a novella by Paul Zachariah. The challenges of this film were very different. One thing was that the terrain was unfamiliar. Also, the milieu was unfamiliar. What prompted you to do this film? Was it the strong story or its distinct theme?

AG: Once my first adaptation worked, it made me lazy to write my own stories. I started looking for other stories. I really liked Zachariah’s story when I read it. The element of cruelty in the story is very extreme. The protagonist is like a psychopath, like a serial killer. Around that time, K.G. George had made the film Irakal. I felt this story would interest him and suggested to him to read it. Some time passed by, and then George told me it was not working out for him. Then I decided to take up the story.

In the film, Thommi (one of the main characters) is very self-effacing character. He can never say no to others, and this makes him a submissive character. The fact that his master shares bed with his wife also becomes a normal affair for him. Though in the beginning he protests and threatens strongly, but gradually he becomes meek and submits to the situation. Thommi even begins to worship his master. Otherwise life would have been impossible for him. The film is about both—the psychology of meek submission and abuse of power.