The geographical setting of Kerala being a narrow strip of coastal land between the Western Ghats to its east and the Arabian Sea to its west not only ensured the relative political and cultural isolation of the region, but also made it conducive for the growth of spices, which were in high demand throughout the ancient world, thus leading to the establishment of trade with large parts of the world.

It is the lure of the flourishing spice trade in the region that is believed to have brought the first Jews to the ports of Kerala. While the exact year of their arrival remains unknown, it is believed that they were traders from the kingdom of King Solomon (970–931 BC). Other speculations speak of Jews arriving from the region of present-day Israel between sixth century BC and first century AD, or from Majorca in the fifth century AD.[1] However, the first physical evidence of the presence of Jews in Kerala is from much later, between ninth to eleventh centuries AD, in the form of copper-plate inscriptions issued by local kings that granted certain rights to the local Jewish community.[2] The Kollam copper-plate inscriptions of AD 849 and the Kodungallur copper plates of AD 1000 are confirmation of the presence of West Asian trade guilds, consisting of Jews, Persians, Christians, Arabs and Zoroastrians, in Kerala.[3]

Several versions exist regarding the origins of the Cochin Jews, with sources pointing to different waves of migration occurring from different parts of the world to Kerala throughout centuries. While Yemenite and Middle-Eastern Jews are thought to have been the earliest settlers, with their arrival being a continuous flow that was not associated with any particular event in history, the arrival of the Sephardi Jews (Jews from Iberian Peninsula, i.e. Spain and Portugal), who came much later (end of fifteenth to sixteenth centuries), is connected with the policies of religious cleansing enacted in Spain and Portugal in AD 1492 and AD 1497, respectively.[4] Furthermore, a study analysing the genetic history of Cochin Jews showed evidence of Cochin Jews having both Jewish and Indian ancestry. Genetic tests discovered that the Jewish gene flow into the community came from Yemenite, Middle-Eastern and Sephardi Jews.[5]

Kodungallur (Cranganore or Shingly), which was a major Indian port in the ancient times, is believed to have been the initial settlement of the Cochin Jewish community until a blend of geographic, economic and political developments in the subsequent centuries led the community to spread out and relocate to, primarily, Kochi and its adjoining areas of Paravur, Chendamangalam and Mala. The Cochin Jewish community thrived in Kerala, coexisting alongside Hindu, Muslim and Christian communities. However, a majority of the community chose to emigrate to Israel in the 1950s, following the formation of the state of Israel in AD 1948.

India is home to five congregations of Jews of which the Cochin Jews have the distinction of being the oldest as well as one of the smallest in terms of member strength, with less than thirty-five members still residing in Kerala. Prior to its downsizing, the Jewish community had made considerable contributions in developing the cityscape over the centuries. Their settlements remain standards around which trade and local markets flourished. Kochi and its adjoining areas continue to house some of the oldest synagogues in India, although in various stages of decay.

The Cochin Jewish Synagogues

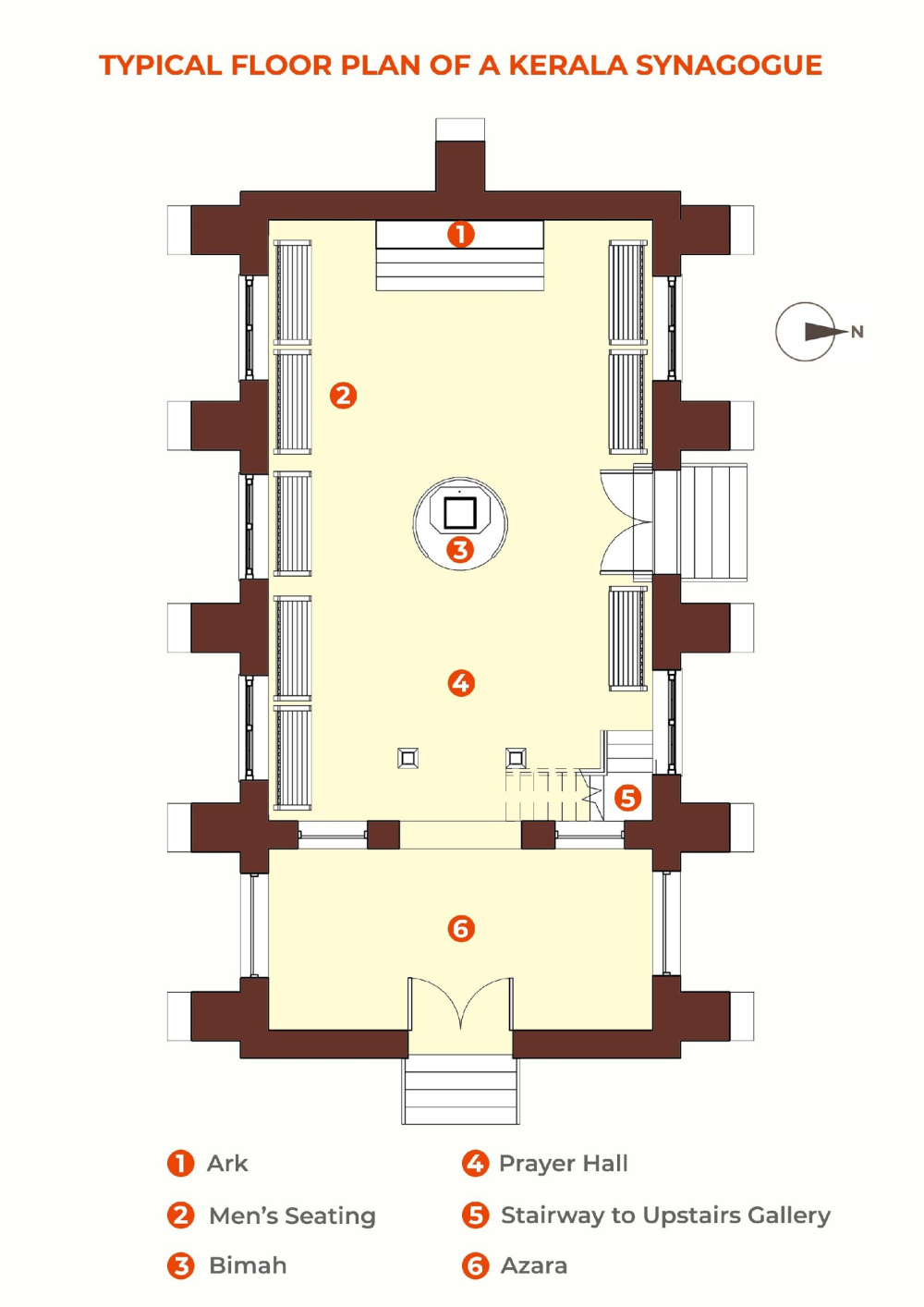

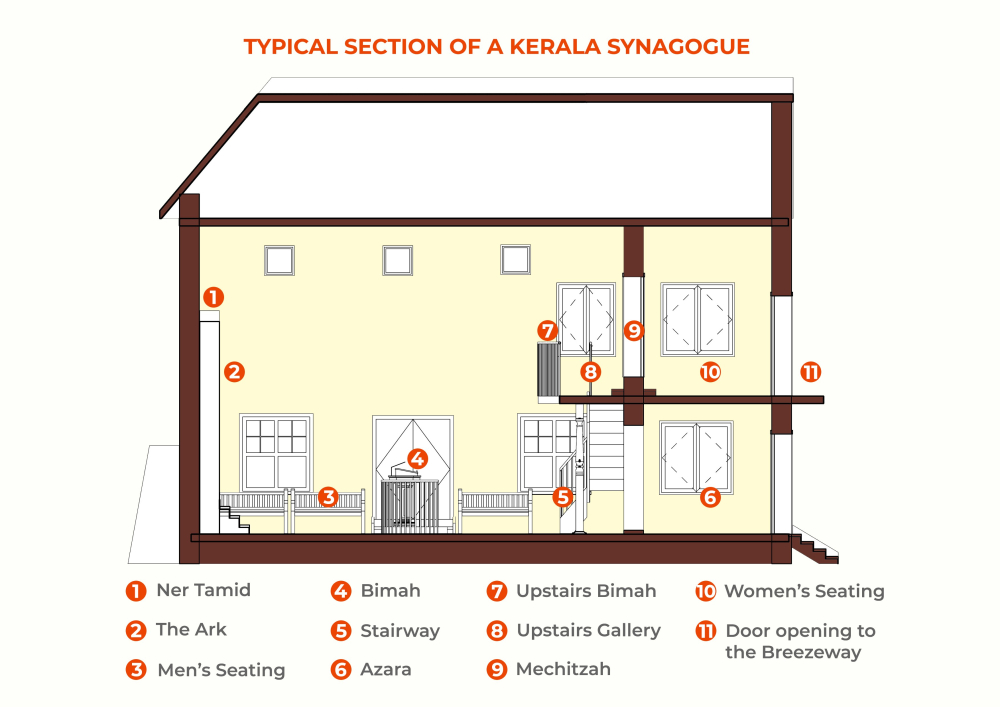

The Cochin Jewish synagogues are unique in that they form a distinct cohesion of architectural styles, illustrating features that are a blend of local and Jewish architectural elements (Fig. 1). While some of these elements were a direct response to the climate of the region and the availability of building materials, some other elements, such as the presence of a second bimah or tebah (podium) in the gallery, evolved to be a feature unique to the Cochin synagogues.

Historically, the Jews as a people were seldom the majority population in any of the regions where they had settled in, and, that, along with the lack of any concrete rules on synagogue design, led to vibrant results in different parts of the world. Apart from certain religious spatial requirements, such as the ark (cabinet containing the Torah scrolls) facing Jerusalem or the central bimah (Fig. 2) for reading the Torah scrolls, the buildings took in features from existing local architectural styles. It may be noted here that there are stark differences in the synagogue designs of the different congregations within India itself. To illustrate, the synagogues of the congregations in urban areas around Mumbai, which were constructed at a much later period than the Cochin synagogues, are larger structures which have taken influence from the architecture of that time found in that city, and are noticeably different from the synagogues in Kerala.

Some of the architectural components of Kerala synagogues are listed below (Figs 3 and 4):

Gatehouse (padippura): The rectangular gatehouse with a compound wall surrounding the synagogue is predominantly a Kerala feature. It functioned as a transition space where meetings were held, and houses the staircase leading to the women’s seating area in the gallery of the synagogue.

Breezeway: A covered breezeway connects the gatehouse to the gallery of the sanctuary, which was the path used by women to gain access to their seating area. The passageway is often adorned with Kerala-style wooden struts.

Azara: Azara is an anteroom inside the sanctuary which serves as a buffer space.

Sanctuary: It is the space where all religious rituals are performed. The sanctuary in Kerala synagogues is usually a double-height rectangular hall. Only men were allowed to occupy the ground floor of the sanctuary.

Ark: The ark is an ornate cabinet which holds the Torah scroll. It is placed on the wall of the sanctuary facing Jerusalem.

Torah Scroll: The Torah scroll is the holy book of Judaism. It comprises the five books of Moses which are rolled up around two heavily ornamented wooden shafts. It is kept inside the ark.

Ner Tamid (Eternal Flame): Ner Tamid is usually located above the ark. It is a lamp that is constantly lit, used as a reminder of the lamp of Menorah in Jerusalem. It is usually powered by electricity, and remains lit even when the synagogue is not in use.

Bimah: The bimah is a raised podium at the centre of the sanctuary, adorned with brass balustrades, facing the ark. The Torah scrolls are read from the bimah by the Rabbi. Men sit on benches placed on either side of the bimah.

Upstairs Bimah: It is an exclusive feature found only in Kerala synagogues. The gallery with the second bimah was used for conducting services on special occasions. It is connected by steps leading up from the sanctuary, which was used by the rabbis, and by the breezeway from the gatehouse, which was used by the women to gain access to the seating area designated for them.

Mechitza (Partition): The women’s seating area has a wooden screen or partition behind the upstairs bimah, and was meant for segregation.

It can be observed here that these synagogues maintained many of the religious and functional space requirements and religious components exactly as it would be observed in synagogues across the world, while having evolved certain features, over the centuries, which are unique to this group only, such as the upstairs bimah and the gatehouse. The extent of elements taken from local Kerala architecture remains high as the buildings were shaped to withstand the extreme monsoons of Kerala (as seen from the hipped roof), while the construction materials used by the community to build these synagogues were locally available. It is to be noted here that vernacular features had permeated the design of the interior of the synagogues as well, for example, the commonly used Indian-style lotus motifs as a decorative element in the interiors of many of these synagogues. Furthermore, the arrangement of spaces that make the synagogue has also been inspired from the architecture of places of worship of other religions which had already existed in Kerala. The axial arrangement of spaces from the gatehouse to the ark of the synagogue is similar to what we might observe in the old temples in the region.

The Seven Synagogues of Kochi

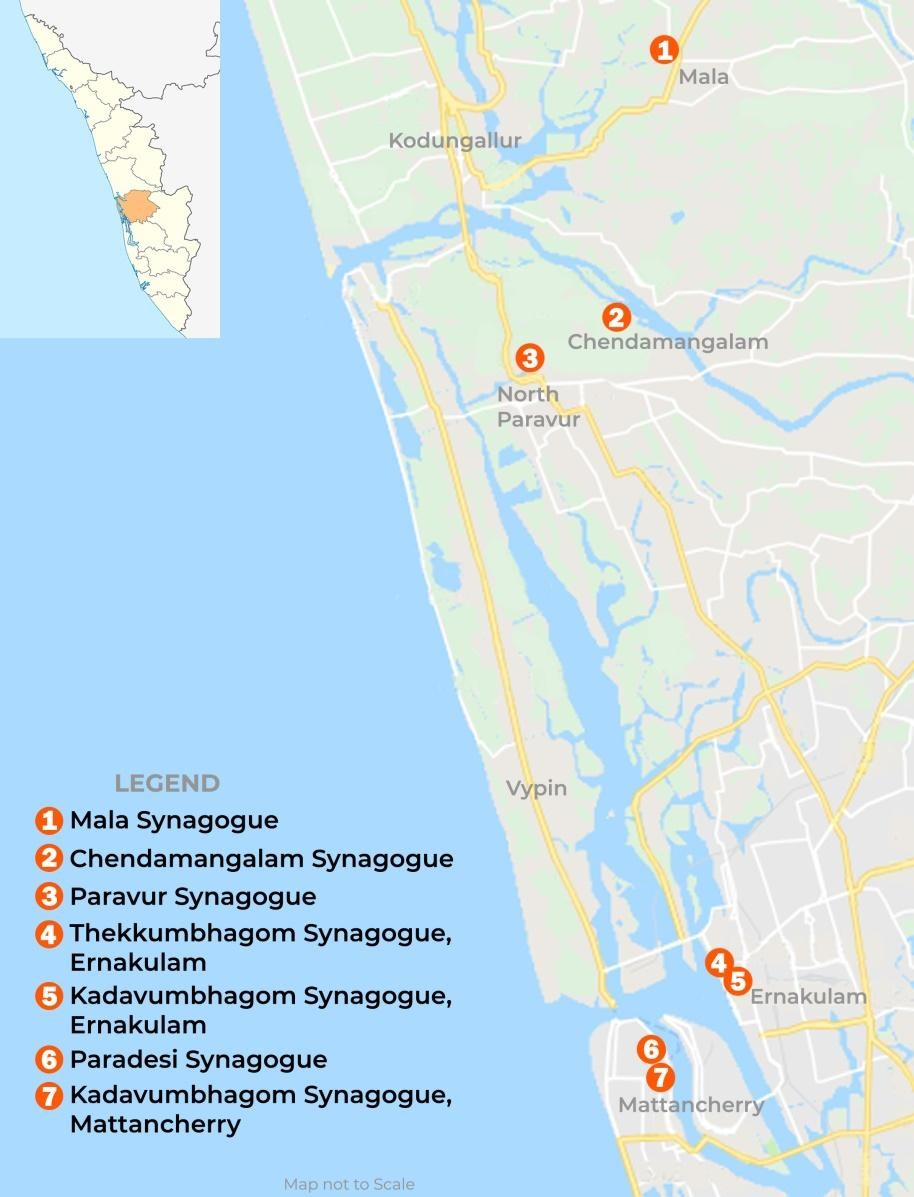

All seven synagogues of the Cochin Jews share certain common characteristics making it part of a distinct group, but no two synagogues are identical. At the outset, it is interesting to note the location of the settlements where the synagogues were built. The early Jewish settlements are believed to have been concentrated in Kodungallur, which used to be the major port city in the region before the emergence of Kochi as a major port. The decline of Kodungallur led to Jewish settlements emerging in the nearby regions of Mala, Paravur and Chendamangalam, each of which has a synagogue of its own. A major shift to Kochi is believed to have occurred later on. Four of the seven synagogues can be found in Kochi, with two in Market Road in Ernakulam city and the other two located in Mattancherry. All the synagogues, with the exception of the Paradesi Synagogue, fell into disuse in the 1950s and 1960s when a vast majority of the congregation immigrated to Israel. Since then many of the synagogues in disuse were subject to alterations or encroachments. However, prudent efforts were able to transform some of the previously abandoned synagogues into museums, active houses of prayer or even tourist destinations, while others continue to be locked and face disintegration. The synagogues are listed below in the order followed in the map (Fig. 5).

Mala Synagogue, Thrissur: The Mala Synagogue is believed to have been constructed in AD 1400, with the building being renovated in AD 1792. It was severely damaged during the 1780s by the army of Tipu Sultan during the Anglo-Mysore Wars.[6] The inscriptions on the frieze in the synagogue’s gallery engraved in Hebrew and Malayalam put the year as AD 1909 when a major refurbishment occurred. The Jewish populace of Mala, as in the case of a majority of the Cochin Jewish community, left for Israel in 1955. Subsequently, the synagogue passed on to the Panchayat. Initially repurposed as a school, the building subsequently fell into disuse. Originally, the synagogue had a gatehouse and breezeway connecting the sanctuary, which was demolished recently after being cut off from the building by land encroachments and constructions.

Chendamangalam Synagogue, North Paravur: The synagogue was built near the Periyar River with local narratives citing AD 1420 as the year of construction, and various accounts citing it as being rebuilt in AD 1614. It currently functions as the Kerala Jews Lifestyle Museum.

Paravur Synagogue, North Paravur: The current structure of the Paravur Synagogue was constructed in AD 1616 on the same site which is believed to have housed another synagogue since AD 1164.[7] It is composed of different spaces arranged axially, starting from the padippura and ending at the ark inside the sanctuary, making it the longest among the Kerala synagogues. This axial arrangement is believed to have been influenced by the spaces of other religious buildings in Kerala at that time which followed a similar pattern. It underwent restoration between 2010 and 2013, and currently functions as the Kerala Jews History Museum.

Thekkumbhagom Synagogue, Ernakulam: Thekkumbhagom means ‘on the south side’. It is believed to have been constructed in AD 1580 and was demolished in the 1930s due to deterioration. The current structure was constructed between mid to late 1930s, and it followed the architectural style prevalent in Kerala at that time, making it notably different from the other synagogues which were constructed a few centuries ago. The lavish use of stained glass windows can be observed here. The synagogue currently remains non-operational.

Kadavumbhagom Synagogue, Ernakulam: Kadavumbhagom translates as ‘the side on the landing place (for boats)’. It is believed to have been built in the early eighteenth century. The synagogue is unique in appearance from the other Kerala synagogues as its front facade has chamfered edges. The synagogue was closed down by AD 1972 when a majority of the members emigrated to Israel, leaving behind not enough men to form a minyan (quorum of ten Jewish adults). The synagogue was eventually vandalised, with all the glass lamps, brass pillars and even the bimah stolen. It has since then been under the care of Mr Elias Josephai who runs a plant and aquarium business, Cochin Blossoms, in the big hall outside the synagogue sanctuary. The synagogue was reopened in December 2018 after renovation.

Paradesi Synagogue, Mattancherry: The synagogue has its roots intertwined with the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal), which, towards the end of the fifteenth century, witnessed concentrated efforts to expel Jews. Spain decreed in AD 1492 and Portugal in AD 1497 to eradicate Judaism from their lands, resulting in the forced exile of the community to other areas. Kochi welcomed these Sephardi Jews, whose growing numbers led to the establishment of the Paradesi (foreigner) Synagogue in 1568. The synagogue was expanded during the Dutch period and a clock tower was added in the 1760s, which is a feature unique to the Paradesi Synagogue among the Kerala synagogues. In addition to the Kadavumbhagom Synagogue in Ernakulam, it is one of the two active synagogues among the Cochin Jewish synagogues at present and remains open to tourists on non-Jewish holidays.

Kadavumbhagom Synagogue, Mattancherry: The Kadavumbhagom Synagogue in Mattancherry was built by the Malabari Jews in AD 1549. Although this synagogue is located close to the Paradesi Synagogue, it underwent constant neglect and much alteration over the decades after the Jewish congregation left for Israel in AD 1955. Like in the Paradesi Synagogue, a gatehouse and an attached breezeway were part of the original structure, which were demolished over the years, and the synagogue ended up being a warehouse for a while. Today, only a shell of the sanctuary remains as the building continues to decay. The interior of the synagogue followed a similar pattern as that of the Paradesi Synagogue. It contained intricate wood work on the ceiling and a gallery with a second bimah, which were dismantled and taken to Israel in 1991, and is currently housed in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

[1] Katz and Goldberg, The last Jews of Cochin; Segal, The History of the Jews of Cochin.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Gamliel, Back from Shingly: Revisiting the Premodern History of Jews in Kerala.

[4] Katz and Goldberg, The last Jews of Cochin; Segal, The History of the Jews of Cochin.

[5] Waldman, The genetic history of Cochin Jews from India.

[6] Waronker, The Synagogues of Kerala, India, 57.

[7] Waronker, 64.

Bibliography

Gamliel, Ophira. 'Back from Shingly: Revisiting the Premodern History of Jews in Kerala.' Indian Economic and Social History Review 55:1. 53–76.

Katz, Nathan and E S Goldberg. The last Jews of Cochin: Jewish identity in Hindu India. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1993.

Segal, J. B. The History of the Jews of Cochin. London: Vallentine Mitchell, 1993.

Waldman, Y. Y., Biddanda A., Dubrovsky M., Campbell C. L., Oddoux C., et al. ‘The genetic history of Cochin Jews from India.’ Human Genetics 135: 1127–43.

Waronker, Jay A. The Synagogues of Kerala, India: Their Architecture, History, Context, and Meaning. Master’s Thesis, Cornell University, 2010.