The state of Telangana counts itself home to 676 libraries, with Hyderabad city accounting for 90 of these.[1] In fact, this is a count of public libraries that fall under either the Directorate of Public Libraries—such as the State Central Library located in Afzalganj (Fig. 1.), or specific to the city, the Hyderabad City Grandhalaya Samstha (HCGS; Hyderabad City Library Association) (Fig. 2.). The HCGS is headquartered at the City Central Library in the neighbourhood of Chikkadpally in Hyderabad and dates from 1960.

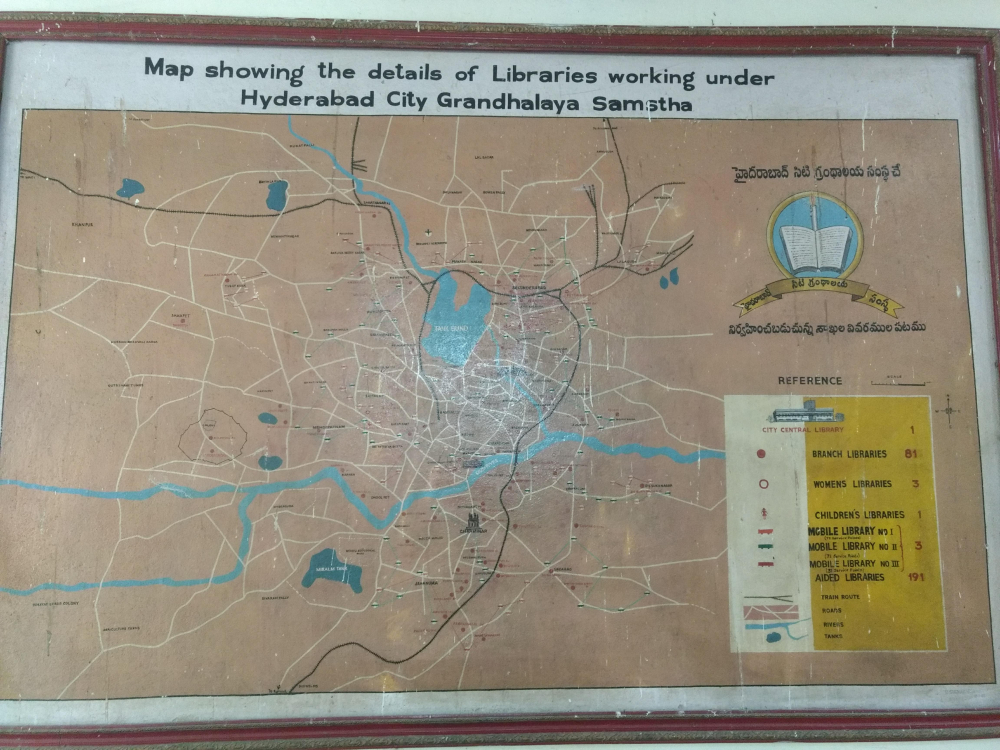

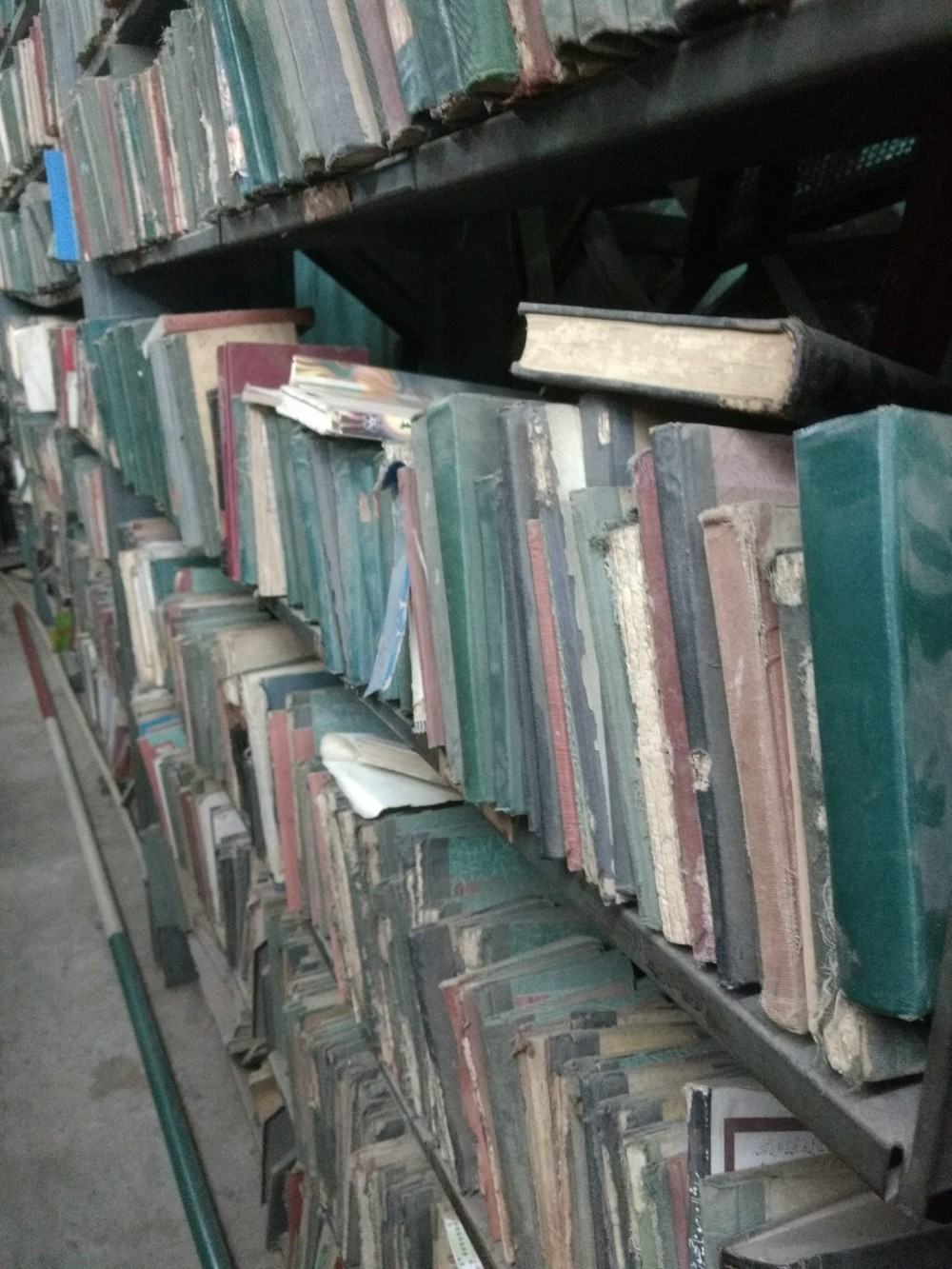

It is supposed to be funded by the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation, which includes a library cess in its revenue stream, and it is supposed to use these funds to maintain all the libraries within its jurisdiction. Maintenance includes the upkeep of buildings, the purchase of books and the availability of adequate facilities for the public to use the library. The system is beset with problems, not least of which is the shortfall of the payments owed to the HCGS. This has resulted in the widespread neglect of the institution of the public library in Hyderabad. (Figs 3 and 4)

Aside from the problems mentioned, however, these numbers also exclude private libraries of different kinds, including informally administered neighbourhood libraries. These will form the core of this module, along with the state-run Afzalganj Library that dates back to the 1890s, for purposes of comparison.

Actual figures about numbers, the histories and present state of libraries in the city can be found in newspaper articles, dissertations submitted to local universities, online resources as well as memories of individuals conveyed through interviews and personal conversation. This module will draw on these to sketch a profile of the range of institutions profiled here. A brief history of the social and political importance of libraries in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries follows, after which the importance and brief profile of personal collections of books in Hyderabad city is discussed and finally, in conclusion, recent initiatives to digitise or fund e-libraries for a new generation of readers are considered in the context of this history. These eight libraries are chosen as examples of the different ways in which this heritage of Hyderabad city is nurtured and preserved against formidable odds.

History: Libraries and Library Movements

The history of the oldest libraries of Hyderabad city goes back to the late nineteenth century, and these ranged from institutions serving a larger social purpose to those attached to educational institutions and what we might call research libraries. A list compiled recently to celebrate old libraries in Telangana records the Prajahita Granthalayam (Public Service Library) as the oldest library in the city; this was founded in Secunderabad in 1870. It is important to remember that jurisdiction over what is Hyderabad city today was split between the British and the Nizam’s government, and many of these libraries were started in areas under British jurisdiction, like Secunderabad—the cantonment area—and Sultan Bazaar (then Residency Bazaar), close to the Old City and the area surrounding the British Residency. An example of the latter is the library of the Young Men’s Improvement Society, established in 1879 by the scientist and educator Aghorenath Chattopadhyay at Residency Bazaar.

The Bharat Gunavardhak Samstha library, still operational in the Lal Darwaza area of the Old City, was founded in 1895 by a group of Marathi-speaking Hyderabadi men inspired by Tilak. (Fig. 5.) Similarly, 1901 saw the founding of the Sri Krishnadevaraya Andhra Bhasha Nilayam, once again in Sultan Bazaar, with patronage from the Zamindar of Munagala (near Suryapet in Nalgonda district), Nayani Venkat Ranga Rao. The founding of these two libraries demonstrates a shift towards the library as a medium to assert and promote vernacular languages and linguistic identity.

Other types of libraries included those attached to elite clubs like the Nizam Club (1884) and to educational institutions like the English-medium Nizam College (1887). Finally, research libraries were started to deal in particular types of books and manuscripts: the Dairat’ul Ma’arif (1888) that is located today on the Osmania University campus, was founded to preserve and publish anew old Arabic manuscripts[2], while the Asafia Library (1891) began with a core donation from the library of Syed Hussain Bilgrami (titled Imad-ul-Mulk, and Director of the Department of Public Instruction in the Nizam’s government). Bilgrami was also instrumental in founding the Daira.

The establishment of libraries formed a major part of the activities of nationalist intelligentsia in the Andhra-Telangana region. Conceived as social reform initiative to spread literacy and contribute to forming a modern public, initiatives to start libraries and encourage reading in villages, small towns and cities were taken up during the nineteenth century in many parts of India, and were, in fact, pioneered in princely states like Travancore and Baroda.[3] The princely state of Hyderabad, of which the city of Hyderabad was the capital, was home to a linguistically diverse population. While a large majority was Telugu-speaking, significant numbers of Marathi, Kannada and Urdu speakers were subjects of the Nizam (the title of the rulers of the Asaf Jah dynasty). As a result of the spread of ideals of education and linguistic assertion, demands emerged to promote languages other than Urdu, the official language of the state and the main beneficiary of state patronage.

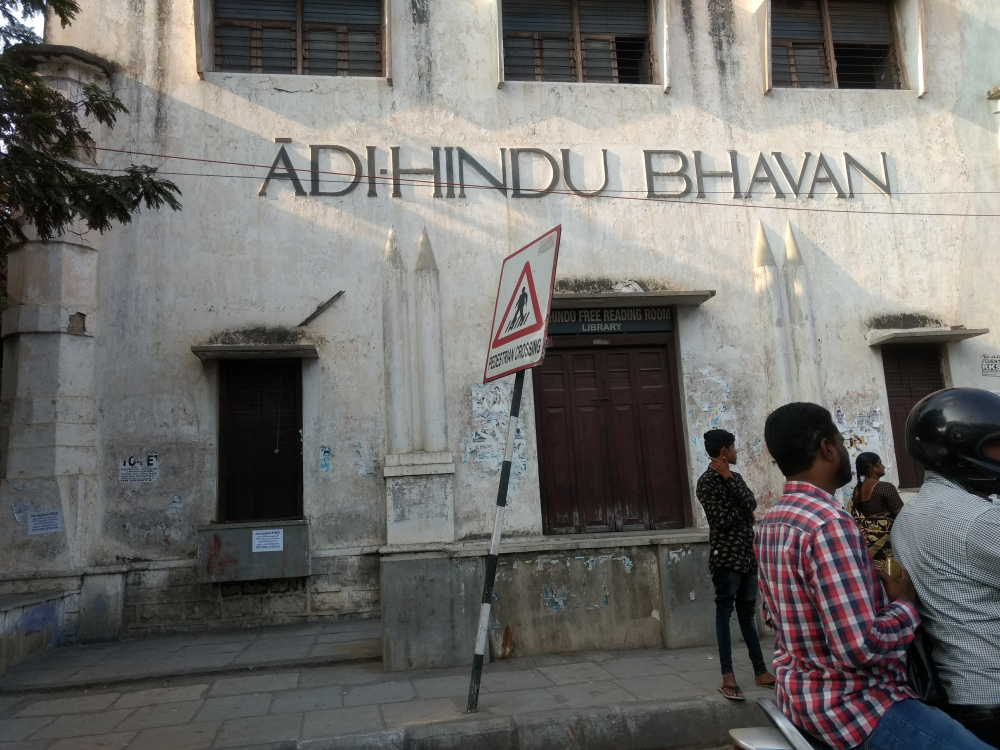

By the early twentieth century, libraries and reading rooms had become full-fledged forms of political expression of different types. In 1911, for example, the Hyderabad Dalit leader and reformer Bhagyareddy Verma started an institution as part of his Adi-Hindu movement with a meeting hall and a library and reading room, in the Chaderghat area just north of the river Musi. (Fig. 6.) In history books, the first public platform to advocate the establishment of libraries and reading rooms in Hyderabad is usually considered to be the Andhra Jana Sangham. This body was founded in 1921 by leading Telugu-speaking intellectuals like M. Hanumantha Rao, and grew into a larger body called the Andhra Jana Kendra Sangham, covering many areas of Telangana by 1922. This explicitly stated its goals as being to ‘establish libraries and reading rooms’ and to ‘collect manuscripts and conduct research’.[4] This ‘library movement’ was seen as a safe non-political route—in the eyes of the government—to political organising.[5]

Personal Collections made Public: Brief Profile of Libraries

In addition to political mobilisation, the well-stocked library continued to be a mark of distinction in the urban milieu of Hyderabad city throughout its life as a princely capital city. Oral accounts and reminiscences suggest that at one time the number of private libraries may have exceeded 15,000. During the late 1930s, for example, the Urdu writer and critic Sibte Hasan visited Hyderabad city and noted in his later memoir titled Shahar-e-Nigaran or ‘The City Beautiful’:

Hyderabadis were crazy about reading books and newspapers (akhbār-bīnī aur kutb-bīnī kā junūn). The city had several bookstores, where you could get books and journals from Lahore, Delhi, Lucknow…basically, everywhere—and people bought and read them with great interest (shauq). There was a shop called Hyderabad Book Depot for English books […] I was amazed to see them sell the writings of Marx, Engels, Lenin and other Communist writers quite openly, without anyone objecting, though these books were banned in Hindustan at the time.[6]

Many of the libraries owe their collections to precisely these practices of book-collecting. The Asafia library, as noted, came from Imad’ul Mulk’s collection; the Urdu Hall library in the Himayatnagar neighbourhood of the new city owes its core collection to yet another aristocrat, Nawab Mehdi Nawaz Jang. It is said that each book contains handwritten notes by the nawab, indicating that he read all of them. This collection is currently being digitised and the catalogue updated.

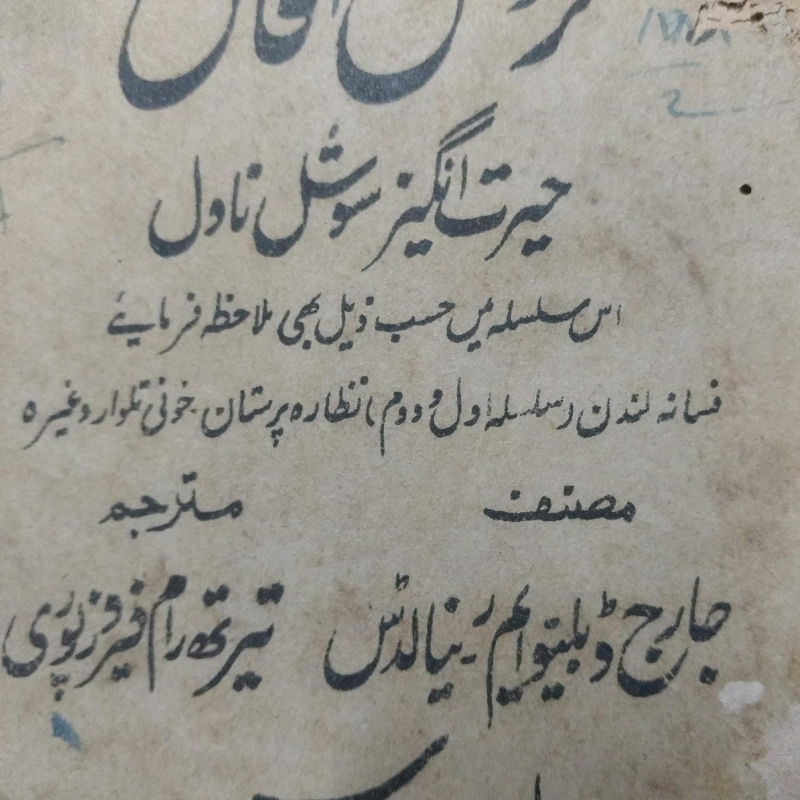

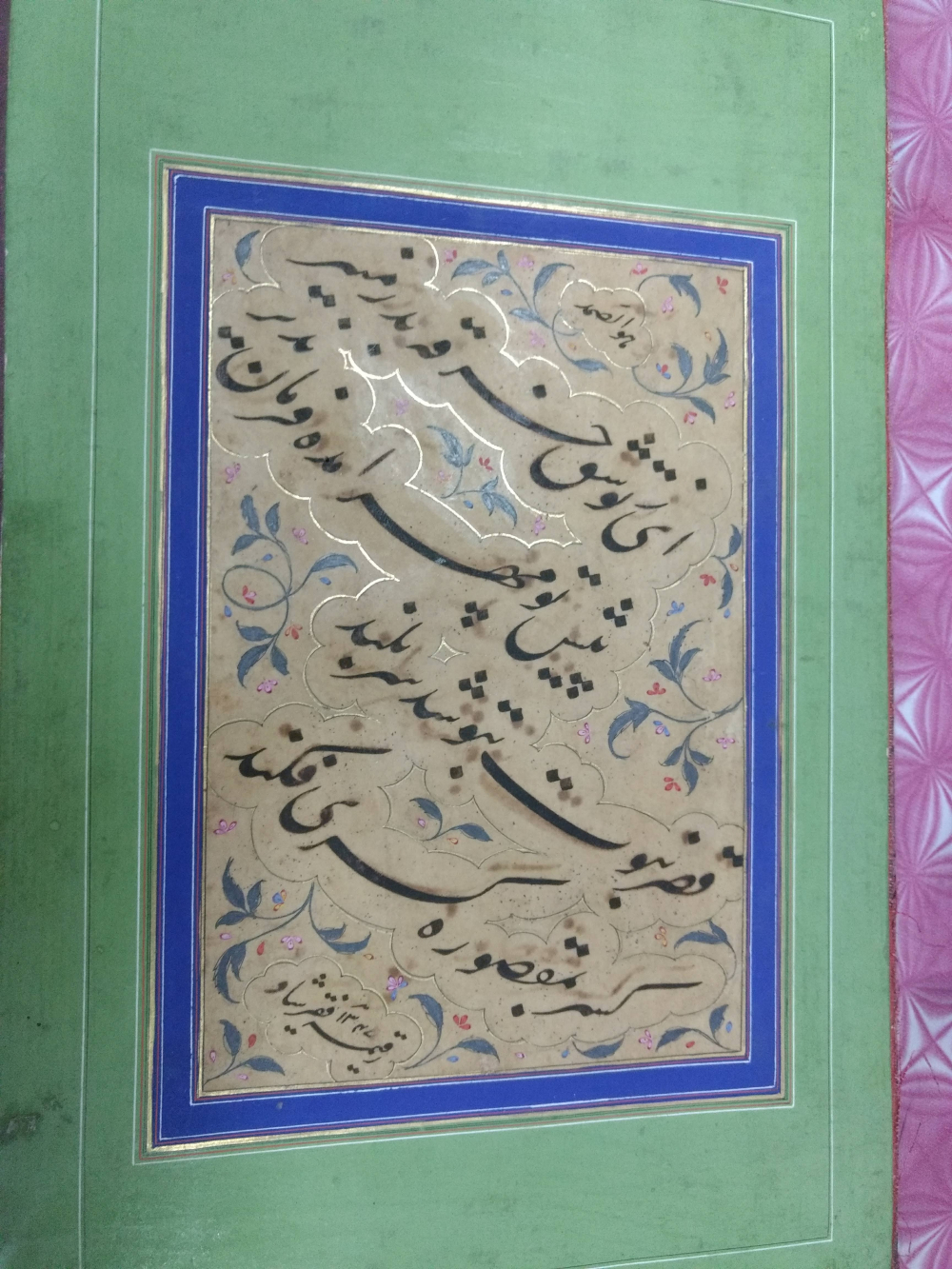

According to the current caretakers, the young men who started the Gunavardhak Sanstha library simply pooled together their personal collections as well as the newspapers they subscribed to in order to get the library going. (Fig. 7.) It contains books in six languages: Marathi, Hindi, Sanskrit, English, Urdu and Telugu, and also the odd volume or framed couplet in Persian which date back from its founding years. (Fig. 8.) Marathi books—children’s books, novels, poetry, autobiographies and biographies, as well as books on music and traditions of religious movements—form the bulk of the collection, and cover the most recent acquisitions. By their own admission, the Urdu collection remains largely unread and uncatalogued because of the absence of Urdu readers among them. It still benefits from voluntary donations from publishers and booksellers based in Maharashtra, as well as old Hyderabadis who want to give away long-nurtured book collections. Because of the community management of the library as a voluntary service, there is no lending or borrowing of books, and cataloguing has just begun as an initiative taken up by the dedicated group of people who see to its day-to-day functioning.

After 1948, increasingly personal libraries were given away or sold off for a pittance as elite Muslim nobility fell on hard times and either migrated[7] or moved into smaller homes where extensive libraries could not be accommodated. An institution like the Idara-e-Adabiyat-e-Urdu (Institution of Urdu literature; founded in 1930 and also known as the Aiwan-e-Urdu), whose distinctive mid-twentieth century building shares the skyline with the new Metro station at Iram Manzil, has found it hard to keep its collection together and flourishing. It was built on the personal property of its founder, the Dakkani litterateur and literary historian Muhiuddin Qadri ‘Zore’, and languishes today in the absence of funds and proper staff. However, the old Urdu, Arabic and Persian manuscripts and books in its collection, as well as its collection of old Urdu newspapers, brings researchers from various universities here fairly regularly. The literary journal Sabras is published by the Idara, which also used to run Urdu classes and certifying exams in the language, but no longer does.

The Anjuman-e-Mahdavia library in Chanchalguda, also in Malakpet, is run by the eponymous organisation Markazi Anjuman-e-Mahdavia (MAM; Central Mahdavi Association), and caters primarily to this community of Muslims who have lived in the neighbourhood for three centuries at least.[8] Much of the private collection of Nawab Bahadur Yar Jang—who was the most significant Muslim leader in Hyderabad state between 1930‑1945—was donated to this library. The nawab was known to have an extensive collection of books in Urdu and English as well as Arabic.[9] While it does not see too many visitors, occasional ones may include school-children accompanied by parents intent on gathering material on the nawab’s life, to participate in the elocution competitions held on that subject by the MAM and other organisations that commemorate his life and achievements.

Possibly the best example of the widespread culture of book-collecting is the library assembled by Mohammad Abdus Samad Khan.[10] The Urdu Research Centre, as his collection was known, is ‘widely considered one of the world’s finest for early Urdu periodicals and printed books.’ Today it lies at the Sundarayya Vignan Kendram (SVK) library, purchased by the University of Chicago in order to catalogue, preserve, and help circulate information about this invaluable personal collection. This also demonstrates one of the fates of these small collections as they enter global regimes of circulation. From a personally nurtured community library the URC may be said to have become an international institution of research, at least formally, to which access is more restricted. After the flood damage to the books in 2000 and a long salvaging process, the collection is housed, uncatalogued, at the SVK’s new spacious building in Gachibowli, near the Financial District, and between the campuses of the Maulana Azad National Urdu University and the University of Hyderabad.

Another route taken is that of the private trust. The Nizam’s Trust Urdu Library at Malakpet, started in 1968, is possibly the best-managed Urdu library in the city. Not only does it cater to the neighbourhood as well as to students and professors of Urdu as a quiet space of reading, it also lends books out through memberships. The collection continues to be updated with new purchases, and the older collection includes manuscripts and fiction, poetry, social science literature, literary criticism as well as newspapers from the early twentieth century. Here, too, initiatives are on to digitise and update the catalogue online. In addition, the Trust has commissioned a survey of existing Urdu libraries in the city, as an update of a previous survey carried out in the 1980s. The updated list of libraries is yet to be made publicly available, but from personal accounts it appears that of the 150 odd libraries that were listed in the previous survey, about a hundred or less are still—and barely—functioning.

Possibly one such library is the General Library and Reading Room in the Red Hills neighbourhood near the Hyderabad railway station in the new city. The personal collection of a locally well-known doctor of medicine, it is today the sole responsibility of an old Muslim woman to whom he entrusted its well-being. It functions in one room on the ground floor of a two-storey residential building. An ironing table abuts the room, with freshly-washed and freshly-ironed stacks of clothes dwarfed by the stacks of books on the dusty shelves. In this space Rukhsana Begum tutors young children in Arabic and Quran-reading for a few hours every day, including weekends. She is supported by the neighbourhood in both her livelihood and vocation—while the library sees few readers now, the space to house the collection of old Urdu novels, journals, memoirs, biographies and autobiographies as well as literary histories and religious commentary is also made available thanks to her local repute. She no longer reads any of the books, but considers it her duty to keep the collection and the library alive for the sake of its founder and his legacy. She welcomes interested visitors as much as the managers of the Gunavardhak Sanstha library, and in the same spirit, though they are unknown to each other and separated by the gulf of written (not spoken) language, community and the physical distance between the Old City and the new.

Digitisation and Heritage

After many years of effort and some sporadic attempts at digitising (scanning material and uploading onto databases like archive.org) collections from the more prominent libraries like the Asafia Library, there is now some discussion of carrying this forward and funding such initiatives in other libraries.[11] Today many of these libraries function as reading rooms for older people and as a space for exam preparation on the part of college and university students, especially those applying to various government posts. As such, the demand for infrastructure and the latest textbooks is high, and the concern for reading, accessing rare genres, or new types of books is neither encouraged nor evident. But all of these libraries bear witness to a long history of promoting just such a curiosity and demand. In most cases they are staffed by dedicated individuals who, with a little financial and organisational help, can recreate a much-needed space for reading and reflection for generations of readers, whether children or adult. The demand exists and manifests occasionally in different places, but in the absence of a sustained effort to recognise and encourage it, the custodians of these old places embodying the material cultural heritage of ‘the city beautiful’ continue to care for them, sometimes mustering support from their communities of readers and neighbours.[12]

Notes

[1] Rohith, ‘Old City Libraries.’

[2] Roosa, ‘Quandary of the Qaum’, 172.

[3] Nair, People’s Library Movement, 35-76.

[4] Bawa, The Last Nizam,124; Roosa, ‘Quandary of the Qaum’, 434.

[5] Innaiah, Political History, 51.

[6] Hasan, Shahar-e-Nigaran, 63-64.

[7] Nanisetti, ‘A Quiet Athenaeum’.

[8] For details, see Ahmad, Studies in Islamic Culture, 167-168; Moin, The Millenial Sovereign, 108‑109.

[9] Ahmad, Savanih, 2006.

[10] Abidi, ‘The Mechanic’.

[11] The Hans India, ‘Efforts on to Develop’.

[12] Koshy, ‘Open Books’.

Bibliography

Abidi, Raza Ali. ‘Voh Mekainik Sahab [The Mechanic].’ Translated by Omar Qureshi. British Broadcasting Corporation, 1975. Accessed February 24, 2020. http://dsal.uchicago.edu/bibliographic/urlc/urc.html.

Ahmad, Aziz. Studies in Islamic Culture in the Indian Environment. Oxford: Clarendon, 1964.

Ahmad, Naziruddin. Savānih-e-Bahadur Yar Jang, Volumes I-III. 2nd ed. Hyderabad: Bahadur Yar Jang Academy, 2006-2007. Accessed February 24, 2020. http://bahaduryarjung.org/biographies.php .

Azam, Kousar J., ed. Languages and Literary Cultures in Hyderabad. New Delhi: Routledge & Manohar Publishers, 2018.

Bawa, V.K. The Last Nizam: The Life and Times of Mir Osman Ali Khan. Hyderabad: Centre for Deccan Studies, 2010.

Hasan, Sibte. Shahar-e-nigārān. Hyderabad: Hussami Book Depot, 1994 (1967).

Innaiah, N. Political History of Andhra Pradesh. Hyderabad: Akshara, 2009.

Koshy, Mridula. ‘Open Books: Why India Needs a Library Movement’. The Caravan, June 1, 2017. Accessed February 24, 2020. http://www.caravanmagazine.in/reviews-essays/india-needs-library-movement/2.

Mantena, Rama Sundari. ‘Vernacular Publics and Political Modernity: Language and Progress in Colonial South India.’ Modern Asian Studies 47, no. 5 (2013): 1678-1705.

Moin, A. Azfar. The Millenial Sovereign. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Nanisetti, Serish. ‘A quiet athenaeum in a noisy neighbourhood.’ The Hindu, Hyderabad, June 17, 2018. Accessed February 24, 2020. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/telangana/a-quiet-athenaeum-in-a-noisy-neighbourhood/article24187718.ece.

Nair, R. Raman. People’s Library Movement. New Delhi: Concept Publishing, 2000.

Raju A.A.N. History of Library Movement in Andhra Pradesh (1902-1956). New Delhi: Ajanta Publications, 1988.

Rohith P.S. ‘Old City Libraries Cry Out for Attention.’ The Times of India, Hyderabad, February 24, 2012. Accessed February 24, 2020. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/hyderabad/Old-City-libraries-in-Hyderabad-cry-for-attention/articleshow/12011506.cms.

Roosa, John. ‘The Quandary of the Qaum: Indian Nationalism in a Muslim State, Hyderabad 1850- 1948.’ PhD diss., University of Wisconsin, 1998.

The Hans India, ‘Efforts on to develop’. The Hans India, October 19, 2017. Accessed February 24, 2020. http://www.thehansindia.com/posts/index/Warangal-Tab/2017-10-19/Efforts-on-to-develop-all-676-public-libraries-in-Telangana-Kadiyam-Srihari/334038.