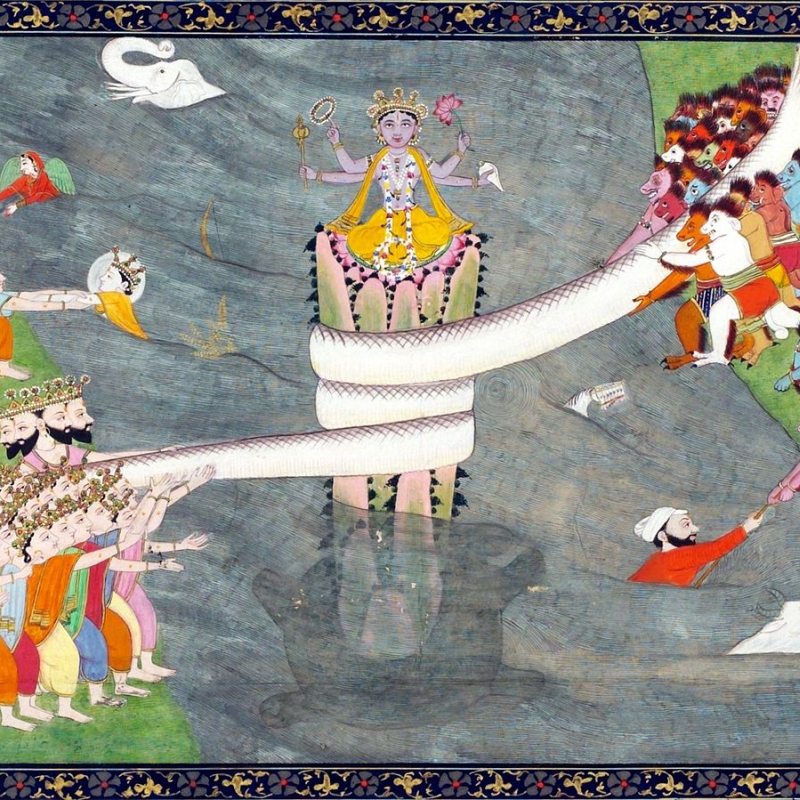

The ocean as a source of wealth—known and unknown—is a message that is strongly ingrained in our cultural memory. We look at how the mythological ‘churning of the ocean’ is an invitation to reflect on the vastness of the ocean, its unlimited potential, its beauty and the possibility of its existence within us as an untapped unconscious. (Photo Courtesy: Unknown (production) [Public domain])

The churning of the ocean (Samudra Manthan in Sanskrit) is perhaps one of the best-known episodes in Indian mythology, appearing in several texts such as the Mahabharata, Vishnu Purana and Bhagavata Purana. Mythologists such as Georges Dumézil and Jarich Oosten compared the churning of the ocean to obtain nectar (amrita) with European myths about ambrosia. The myth has also been the subject of many traditional paintings that visualise and etch the act of ‘churning the ocean’ into the cultural memory of Indians.

While it is easy to read the myth as a tale of universal aspiration to achieve immortality, the symbols and metaphors contained in it are rather profound. The rich and complex symbolism of the ‘churning of the ocean’ myth is deciphered and interpreted in terms of yoga and its analogical ways of thinking about the body and the cosmos.

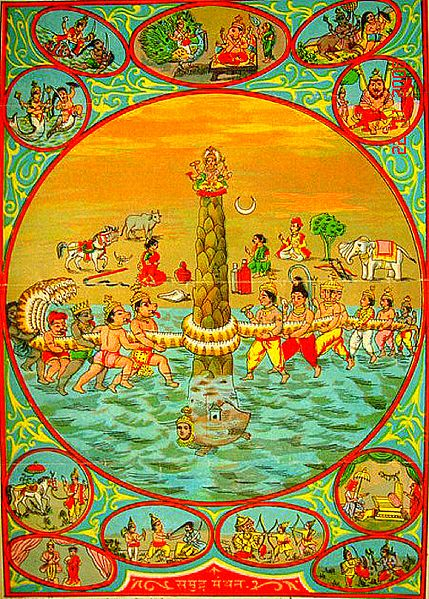

The churning requires both the Devas and the Asuras, and signifies that one needs to come to terms with both the demonic and divine qualities within oneself (Courtesy: Bazaar Art Print [Public domain])

In a retelling of the myth in Roberto Calasso’s Ka: Stories of the Mind and Gods of India, Vinata narrates the story to her son Garuda:

In the beginning, not even the gods had the soma. Being gods wasn’t enough. Life was dull, there was no enchantment. The Devas looked with hatred on the other gods, the Asuras, the antigods, the first born, who likewise felt keenly the absence of the soma. Why fight at all, if the desirable substance wasn’t there to fight for? The gods meditated and sharpened their senses, but there would come a day when they wanted just to live. Gloomily, they met together on Mount Meru where the peak passes through the vault of the heavens to become the only part of the world that belongs to the other. The gods were waiting for something new—anything. Vishnu whispered to Brahma, then Brahma explained to the others. They had to stir and churn the ocean until the soma floated up as butter floats up from milk.

The Churning and Chakras

Using Mount Meru as the rod and Vasuki—the king of snakes who adorns the neck of Shiva—as the rope, the Devas and the Asuras churned the milky ocean. Since the Asuras were holding Vasuki’s head, they had to deal with his poisonous fumes. To stop Mount Meru from sinking, Vishnu took the form of a tortoise and supported the base of the mountain. The description in the myth says that Vasuki wrapped himself around the mountain three-and-a-half times, pressing the mountain at seven critical points. Many interpretations of the myth see this as an analogy of the seven chakras of the human body mentioned in yogic literature and of a snake (kundalini energy) binding them. The myth of churning the ocean corresponds to a yogi practising his art (including meditation) to stir his vast ocean-like unconscious in order to find the nectar (soma) in his mind and merge with eternity. The churning requires both the Devas and the Asuras—this means that one needs to come to terms with both the demonic and divine qualities within oneself. It is commonly believed that both the ocean and the unconscious are vast reservoirs of unknown wealth. Carl Gustav Jung once wrote, ‘The sea is the favourite symbol for the unconscious, the mother of all that lives.’

Also read | Kumbh Mela: Do Our Vedic Texts Mention this Unique Pilgrimage?

The Removal of Poison

When the gods and demons stirred the milky ocean, what first appeared was Halahala—a highly pernicious poison that threatened to destroy the entirety of creation. The king of yogis, Shiva, swallowed the poison, which turned his neck blue. In some versions of the myth, his consort Parvati catches him by the neck to stop the poison from advancing further. As the blue-necked-one, Shiva acquired the name ‘Neelakanta’ after the incident. Yoga practitioners explain the event as a demonstration of the unconditional protective power and grace of Shiva. For them, Halahala symbolises the eternal maya (illusory world) and its conditioning; its psychic poison has to be encountered and overcome at the Vishuddhi chakra, believed to be at the centre of the throat.

While in some versions of the myth, the amrita (or soma) finally appears in the hands of a physician called Dhanvantari; in others, the nectar appears in an earthen pot held by Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth (Courtesy: [Public domain])

The Treasures from the Ocean

After the poison, gems (ratnas) started appearing from the ocean. The gems stood out in a column of light. Different versions of the myth still argue over how many there were and in what order they appeared. Apart from the gems, a white horse, divine nymphs (Rambha, Menaka, Punjisthala, Varuni), a white elephant (Airavata), a physician (Dhanvantari), the moon, a divine flower (Parijat), a seven-headed horse (Uchchaihshravas), a wish-fulfilling cow (Kamadhenu), a valuable gem (Kaustubha), a powerful bow (Sharanga) and a boon-granting tree (Kalpavriksha) appeared during the churning of the ocean. Calasso writes:

. . . one thing is certain: the amrita could only appear within the procession of gems, within the sequence woven over the epiphanic veil. Nothing that appeared there was new or unheard of. Everything that emerged the depths had emerged before. And, yet, everyone was amazed: because now existence was being formed, composed. With the churning of the ocean, the gems that have ever sparkled along the seams of existence were once again brought into being, as second nature, elaborated, fixed and separate substance. The gods toiled like slaves in smoke-filled workshops to have these emblems, seals of perennial existence, shine forth anew. ‘Elaborate the emblems and existence will follow,’ such was their motto, and so it was. Then they left men to their own devices in the tangle of the existent world.

Also Read | Kamadhenu: The Pleasures of Giving

Yoga practitioners explain the array of gems as forms of knowledge and beauty.

Rahu and Ketu

In some versions of the myth, the amrita (or soma) finally appears in the hands of Dhanvantari. In a few other versions, the nectar appears in an earthen pot held in the hands of Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, who also emerges from the ocean. Though a few boons from the ocean were shared with the demons, the nectar was meant only for the gods. Vishnu had to ensure that none of the demons got a taste of the nectar. He took the form of Mohini, an enchantress, and distracted the demons until the gods had consumed the nectar. However, one of the asuras, Rahuketu, disguised himself as a god and managed to consume some of the amrita. Vishnu cut off his head before the nectar could reach his throat. Afterwards, the head and body were individually known as Rahu and Ketu—two separate entities that became shadow planets in the astrological systems of India. Regaining their strength after consuming the nectar, the Devas defeated the Asuras.

The ‘churning of the ocean’ myth is an invitation to reflect on the vastness of the ocean, its unlimited potential, its beauty and the possibility of it existing within us (Courtesy: English: thesandiegomuseumofartcollection [Public domain])

Origins from a Myth

Many of the gems and boons that appeared from the ocean have mythologies of their own, with the ‘churning of the ocean’ considered to be the original myth. The origins of certain art forms and festivals further extend this ocean myth, giving it a life of its own. For instance, it is believed that Kerala’s Mohiniyattam dance form originated when Vishnu took the form of Mohini and danced to prevent the Asuras from consuming the nectar. It is also believed that a few drops of nectar fell on four different spots on earth: Haridwar, Prayagraj, Nashik, and Ujjain. The Kumbh Mela is celebrated in these towns every 12 years. However, this association came about as late as the 18th or 19th century.

Also Read | How did the World, and its Many Stories, Begin?

The ocean as a source of wealth—known and unknown—is a message that is strongly ingrained in our cultural memory. The ‘churning of the ocean’ myth is an invitation to reflect on the vastness of the ocean, its unlimited potential, its beauty, and the possibility of it existing within us as an untapped unconscious.

Views expressed are personal.