Around 34 kilometres from the city of Calcutta, removed from the humdrum of the metropolis and still further from its intellectual cacophony, lies an unpretentious yet fascinating site. This is the site of Chandraketugarh, tucked away near a small village called Berachampa in the North 24 Parganas, West Bengal. Chandraketugarh remains one of the most important early historic urban coastal sites of eastern India. Though seemingly insignificant, it is far from being such in the works of geographer Ptolemy and the Periplus of the Erythrean Sea, two of the most important early non-Indic sources frequently used in historical research, who identify it as the ancient capital of Vanga and possibly of the kingdom of Gangaridae.

Today visitors to the site would hardly encounter the aura of an urban coastal town that once engaged in international trade, seeing rather barely anything more than a green mound. While the mound suggests some archaeological excavation was carried out once, the green suggests negligence thereafter. Chandraketugarh is, however, not entirely unknown, but it is popular for all the wrong reasons. Numerous artefacts collected from the site lie at the heart of a worldwide illegal antiquities market. It is a remarkable irony that while a terracotta rattle recovered at the site is auctioned at one of Christie’s auctions at the Rockefeller Plaza in New York, the site that produced it lapses in abject neglect. This article, emerging from the dire need to bring to light the need to protect and rescue historical sites, intends to address this irony and possibly redress it.

The year was 1905. India was dealing with its more immediate problems under British rule. It was also the year when the partition of Bengal happened, a momentous and scarring event in the history of the subcontinent. It was also at this time that Tarak Nath Ghosh, a doctor by profession, had his curiousity and interest aroused by two mounds, surrounded and covered by forestation, with broken bricks and pottery scattered all around and over them. The names were the same as they are now—Khana Mihirer Dhipi and Chandraketugarh—and so was the story about a mysterious king. But nothing else was known. Ghosh’s curiosity led him to write a letter to the then chief of the eastern circle of the Archaeological Survey of India, A.H. Longhurst. This was the first time that Chandraketugarh saw the light of day as a historical site.

The history of Chandraketugarh goes back to pre-Mauryan times, that is, the 2nd century BCE. Scholars have suggested that the site has seen continuous occupation since, throughout the Sunga-Kushana period (preceding and in the early centuries of the Common Era), followed by the Gupta and the Pala-Sena periods. Apart from being a site with a long period of settlement, several other factors make Chandraketugarh significant historically. The first is its likely position in a network of international trade. The Greek geographer Ptolemy in his famous Geographia gave a detailed account of the lower Ganga and the region it traversed. Among the four towns that he mentioned, the town of Gangaridae has been identified as Chandraketugarh by several historians. While scholars have argued over whether the site had direct trade relations with Rome, it is highly likely that even if there were no direct relation, it was part of a much wider network in metal trade. The abundance of coins unearthed points to that. Archaeologist Dilip Chakrabarti suggests that this was during the second urbanisation, of which coastal Bengal had felt a direct impact even if for a short time.

The other aspect that stands out with regards to Chandraketugarh is the large number of terracotta objects/artefacts unearthed from the site. Ranging from seals, pottery, rattles, toys, figurines to plaques, the plethora of terracotta art sketches a vibrant picture of early urbanism and cosmopolitanism and also gives us a glimpse into the lives of the people. What makes terracotta objects invaluable for studying a region and its history is the fact that they are a form of expression that contain more local elements, and elements that are difficult to depict in other forms of ancient art such as stone sculptures. Of early historic sites from eastern India, Chandraketugarh has yielded the largest number of terracotta artefacts.

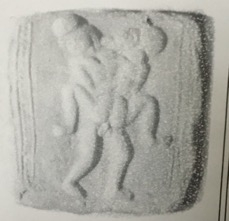

One fascinating element of the terracotta of Chandraketugarh is the erotic art on the plaques. Usually when one thinks about early Indian erotic art the first names that comes to mind is the Khajuraho temple complex belonging to the Chandella dynasty of the 10th‒11th centuries or the Konarak temples belonging to the Eastern Ganga dynasty of the 13th century, both much later than Chandraketugarh chronologically.

Fig. 1: Erotic scenes depicted on terracottas (Several other images of this kind are listed in the work 'Chandraketugarh: A Lost Civilization')

Archaeologically speaking, six periods are distinguishable from the excavations done at Chandraketugarh and the artefacts unearthed. The first period goes as far back as the 4th/3rd century BCE and has yielded specimens of Northern Black Polished Ware and Grey Ware, two characteristic pottery styles of this period, and also punch-marked coins. The early centuries of the Christian era were marked by the presence of terracotta objects, copper coins and stone beads. Terracotta art proliferated in the third period, accompanied by rouletted ware and ceramic vases. Proper structural remains, most likely of a temple, were unearthed during the Gupta period. The fifth and the sixth periods, belonging perhaps to the post-Gupta age, yielded a large number of terracotta objects and most importantly a habitation/temple structure known as the Khana Mihirer Dhipi. Among the structural remains on the site, the ruins of what have been identified as a temple complex is perhaps the most important, as it not only provides concrete material evidence of this otherwise elusive structure but also represents several of the important features of early Indian architecture. Elements such as columns, pavilions, toranas (gates), vedikas (small enclosures around a tree or plant, in most cases for the purpose of worship), indoor architectural patterns, etc., have been located.

But how was this site discovered? As historical discoveries go, India has its fair share of great ones—starting from the identification of Pataliputra by Alexander Cunningham to Rakhaldas Banerji’s stumbling upon the ruins of Mohenjodaro. Chandraketugarh did not have such a momentous discovery; in fact, it was discovered the way many sites are discovered, by accident, during house or road constructions. The artefacts that surfaced then, however, caught the attention of several prominent archaeologists and historians but not before they were practically urged in this direction by local antiquities enthusiasts, such as Tarak Nath Ghosh. One of the first people to visit this site was A.H. Longhurst, the British archaeologist and art historian. The site, however, caught the attention of Rakhaldas Banerji himself, who visited the site in 1909, much before he rose to fame with his discovery of Mohenjodaro. He was of the same opinion as Longhurst, that as far as structural remains go, there is not much to be seen at the site of Chandraketugarh itself; what caught his attention was the outstanding number and variety of artefacts shown to him. The period of his visit was long before any proper excavation had taken place but even without that it didn’t take long for an exceptional archaeologist such as Banerji to recognise the fortification and the fact that the entire site spanned much more than just the fortified area. It wasn’t until a decade later that a report was published by K.N. Dikshit, the then superintendent of the eastern circle of the Archaeological Survey of India. It was mostly due to the initiative of historians and archaeologists such as Kalidas Datta, Deva Prasad Ghosh, Kalyan Kumar Ganguly and Kunja Govinda Goswami that the Ashutosh Museum of Art excavated the site between 1955 and 1967. In 2000, another excavation was undertaken by the ASI, which, however, remained incomplete, its reports unpublished.

Despite its importance, why has Chandraketugarh failed to make it to the front pages of historical research? What makes it less popular than a site such as Tamralipta/Tamluk, which is situated quite close to it but seems to be completely detached from Chandraketugarh? Why the invisibility? The answer to this can be found within the larger problem of archaeological research in this country, particularly in relation to coastal sites. Coastal or marine archaeology is the branch of archeology that specifically deals with the areas around rivers, seas and oceans, and the study of settlements, people and their lives in relation to the waterbody near them. It is an exclusive branch of archaeology as it brings out the specific elements of coastal life that are widely different geographically and, hence, in every other way from land-bound areas. It is also rather difficult because of the volatile nature of the areas in and around the coast, where places and sites get submerged and are difficult to excavate.

The lower half of Bengal, marked mostly by the archipelago of forested and semi-forested islands at the deltaic part and a number of erratic yet powerful rivers, is one of the most complex geographical and socio-cultural regions of the entire Indian subcontinent. The riverine system had much to do with the irregularity that the deltaic region was associated with: the rivers were constantly shifting their courses as a result of which the entire delta was shifting eastwards. The nature of the soil in coastal Bengal makes it even more difficult for sites to continue and for excavations to be carried out. This is one of the major reasons for Chandraketugarh having remained buried and studies remaining inconclusive.

The other crucial limitation on research on Chandraketugarh is the lack of textual and epigraphical material. The sources that mention Gangaridae do not give a specific location that would point clearly to the site of Chandraketugarh. There is also a lack of inscriptions with specific names—of a place, a kingdom or a king. Although multiple inscriptions have been found on the pots, potsherds, plaques and seals excavated, they contain no credible information, and also they are considered by historians to have been written in a script that is a combination of the two major scripts of early India—Brahmi and Kharoshthi.

Coming to the actual place, one finds several legends associated with the name Chandraketugarh. It is said that the area has been named after King Chandraketu, whose historical presence has not been established. Very little is known about this king and several authorities believe him to be fictitious. Two popular claims survive: some scholars have argued that Chandraketu was none other than Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Maurya dynasty, while recent studies have suggested that Sandrocottus, a king mentioned in the Greek accounts (and until recently identified with Chandragupta Maurya), was actually a reference to the king Chandraketu.

The Khana Mihirer Dhipi, a structure belonging to the Gupta period, is named after two popular characters in history. Khana was a learned woman, believed to be the daughter of the astrologer-mathematician Varahamihira. The legend of Khana still resonates in Bengal. Her knowledge and the accuracy of her predictions threatened even the authority of Varahamihira, who eventually conspired to cut her tongue off and silence her. The expression ‘Khanar Vachan’ (the words of Khana) is still popular in Bangla for an occurrence that is inevitable.

Fig. 2: Khana Mihirer Dhipi

The Khana Mihirer Dhipi is one of the two major sub-sites identified at Chandraketugarh. The other, almost a kilometre away, is rather misleading in appearance owing to the state of its preservation. Considered by archaeologists to be a fortification, the site looks no more than an empty ground with a mound covered in green grass extended longitudinally. It could easily pass off as a calm and quiet picnic spot, and it would have were it not for the rusting board put up by the Archaeological Survey of India, warning that any kind of picnic-like activity is forbidden here.

Fig. 3: The site of the fortification at Chandraketugarh

The collection from the site is enormous. The largest consolidated collection is, of course, at the Ashutosh Museum of Calcutta University. The State Archaeological Museum also has a substantial collection of artefacts; however, it doesn’t get many visitors. What makes an even more interesting story is the fact that a large collection of artefacts is in the possession of private collectors. In fact, in all honesty, Chandraketugarh is one of the few sites that have been largely at the mercy of private collectors all over the world. Now more than ever it is important to keep in mind how these collections are acquired.

The politics of plunder

The irony that haunts Chandraketugarh is that it makes more headlines in newspaper reports than in history books, due to the tremendous extent of illegal activities in relation to procuring artefacts and selling them to famous auction houses. The museums that display objects from Chandraketugarh are all over the world. The most popular ones are Musée Guimet in Paris, Linden Museum and the Museum of Indian Art, both in Germany, the Ashmolean Museum in the United Kingdom and probably also the Victoria & Albert Museum and the British Museum. In India, they can be found in several private collections (that of Dilip Maite being one), the State Archaeological Museum of West Bengal and the National Museum of India in Delhi. The last has one figurine from Chandraktugarh on display in the Early Historic Gallery.

So the questions that arise then are: Where are the artefacts going? How are they going out of the country in such large numbers despite the laws in place for their protection? And why is the site itself lying in obscurity?

Chandraketugarh’s popularity is overwhelming in the international antiquities market. Auction houses as big as Sotheby’s and Christie’s auction objects from the site, which are sold at an extremely high rate. It also makes one wonder about the network of smuggling within the country that enables such a thing to happen. The networking, of course, begins at the grassroots where locals collaborate with dealers in getting an excavated object out of the site behind the back of its supposed protectors and into the international market. And this entire process involves the making of large profits.

A conversation with historians, archaeologists and museum authorities sheds light on this highly intricate and circumspect network; a network not just for smuggling an artefact but also for manufacturing fake ones from moulds. Moulds are interesting artefacts themselves. Often, they are originals that help to create fakes; at other times moulds are also manufactured. Fakes are usually made from parent moulds, which make the product undetectable even to expert eyes. Professor Joachim Karl Bautze of the South Asia Institute at Heidelberg University, the author of Early Indian Teracottas, elaborated in an interview how fake objects are created and how all over the world even famous museums often exhibit fake artefacts.

Another intelligent way of making fakes is by joining two artefacts, one original and the other a fake. In several cases the people at the local and regional levels attain expertise in creating these fake objects. Incorporating the locals within this larger network of illegal antiquities trade has great benefits since it is easy to exploit them with the lure of monetary benefits. This also makes way for incredible profits for the dealers, who pay the bare minimum to the locals for the excavated antiquities, which in turn are sold to private collectors or auction houses for a large sum of money. On the other hand, the locals accept whatever they get in preference to handing over the artefact to government officials where there is no likelihood of any remuneration.

Reckless digging is another issue that has troubled the site of Chandraketugarh. This mostly happens during constructions of roads, telephone towers and even residences. There are many newspaper reports, mostly in Bangla, that report the discovery and then subsequent damage to artefacts and objects found while digging for the construction of telephone towers. These instances also point to the gross violation of the law in protection of archaeological sites that forbids any sort of construction within 100 metres of the perimeters of a protected site.

Politics of preservation

What then can be done to ensure the safety of such an invaluable sites such as Chandraketugarh? And who can be entrusted with that task? These two questions are perhaps the two main issues that plague archaeological research in this country. Despite their many guardians, monuments and sites see a different reality on the ground as far as their protection is concerned.

Protected monuments have three demarcated segments in and around them which are specified by legislation: a protected area, a prohibited zone and a regulated zone. The protected area is the monument itself, the prohibited zone is the area within a 100-metre radius around it where no construction is allowed. The regulated zone of some 200 meters beyond the prohibited zone (which can be increased if necessary) requires clearance from the relevant authority before any change takes place within it. The purpose of this zoning is twofold, first, it is supposed to protect sites that can be endangered by human activities. It is similar to the zoning around tiger reserves where a core area is set apart for the animals to live in, where human disturbance is not permitted, while in the surrounding buffer zone limited human activity is allowed. Second, it helps in providing an aesthetic perspective to monuments (Lahiri 2017:79).

These are the most basic guidelines provided to ensure preservation and protection of a site/monument. While there are many instances where this regulation is not followed, the case of Chandraketugarh is even more problematic not only because of encroachment but also abandonment. The photo gallery attached to this project would be a reference point in understanding this. The first site, Khana Mihirer Dhipi, is presently barely anything more than a spot for a lovers’ meet and youngsters looking for a short break. The other site, i.e., the fortification area, is entirely isolated from the main road with nothing to point to its exact location except for the kindness and reliability of a local passer-by. The site itself is entirely empty. One can’t help but look at the warning signs of the ASI that prohibit any kind of picnic-like activity at the spot and wonder that maybe the absence of such prohibitions would have made the site a little more popular than it is.

Fig. 4: The path that leads up to the site

What would be the position of authorities with relation to this particular site? Utopian plans for a glorious museum have been on the minds of several, so they claim. The headquarters of the State Archaeological Department blames a past government for its inaction. The State Archaeological Museum is barely anything more than a godown for antiquities with half its galleries closed for the public. From recent news and newspaper articles, one gets the whiff of the reality of a museum near the site. It is perhaps more of a problem than a remedy as the museum itself has found barely anything more than a location, while on the other hand private collectors such as Dilip Maite are asked to hand over their entire collection, which has been barred from public view (as observed from a recent visit to the site and an attempt to look at his collection). Archaeological reports are not published for public viewing and are to be encountered mostly through the works of historians or archaeologists.

The other problem is the matter of staff. Does the responsibility of archaeologists and institutions that promote archaeology and heritage management end with discovering new sites? If encroachment, smuggling and creation of fakes are problems that are so blatantly visible and providing ready material for newspaper headlines, why is the overwhelming lack of manpower within the Survey not addressed?

In 2010 the ASI stated on record that its staff strength did not permit the deployment of even a single person on a regular/full-time basis at more than 2,500 of its monuments. This means that more than two-thirds of India’s centrally protected monuments are poorly guarded (Lahiri 2017:88)

Chandraketugarh is such a site. In fact, on a busy day one would hardly find a living soul apart from a few cattle and maybe a couple of cattle owners going about their business. And this is important to note because we are talking about a site that has produced artefacts popular and expensive enough to be in important cities all around the world and often in the possession of very important people. Even if one comes to terms with the idea that antiquities’ trading is a problem that cannot be entirely eradicated, how does one come to terms with this sort of callous abandonment?

Thus, individual antiquarianism comes to the rescue of such a site as Chandraketugarh. As has been said before, a large collection of Chandraketugarh artefacts are with individual private collectors who have often collaborated with historians and museums, opened up their own collections for public view and assisted historians and archaeologists to reconstruct this elusive history of Chandraketugarh. But private collectorship also has its drawbacks. While there are many genuinely invested in protecting whatever is unearthed, there are others whose interests might be purely motivated by economic gains and by what is called ‘acquisition of culture’. In fact, the latter is the foremost reason behind antique thefts and smuggling of artefacts to foreign countries. Antiquities are also often considered by many as safe investments like gold, land and art. And if all these fail, it is at least a really absorbing pastime.

Recording the case studies of antiquities’ smuggling is well beyond the scope of this work. But the more pressing question is that how can it be dealt with. Archaeologist Dilip Chakrabarti suggested that the entire blame of looting India’s antiquities cannot be laid only on the unlicensed/licensed antiquity dealer and the general public oblivious of the country’s historical heritage. The blame would be on India’s policymakers as well. He urged looking at this problem in not so complicated and regimented a manner. It would be futile to hope for a day when the looting of antiquities would stop being commercially profitable and the demand for antiques to die out in the international market. In fact, acknowledging this problem would bring out several other solutions to deal with it.

The smartest way to curb this problem would be to eliminate the scope of profit. And this can be achieved with reframing of the laws. The laws need to be more transparent and people-friendly. Chakrabarti termed the act of 1972 as ‘draconian’ since it made possession of artefacts by ‘a god-fearing Indian a criminal offence’. And this term is quite appropriate since in a country where there is limited literacy, the entire exercise of registering the object found with three copies of the photograph and other details within a very short time becomes very tedious. And it becomes even more tedious when there is a chance of making easy money by just handing it over to an antique dealer.

But more than law or regulations or the elimination of a scope of profit, what may be more important, as one can realise looking at Chandraketugarh, is the need for basic historical knowledge of a place. The people at Berachampa, which is the place of the site, barely know anything about its history other than the lore of King Chandraketu. Technical terms of archaeology or the difficult dates of history will not be of interest to a layman. But local schools can start by incorporating bits and pieces of whatever is known of this site. The people who are finding objects and handing them over to antiquities dealers and even helping to make fakes, can be educated about their economic if not its historical value and the fact that they might make a better earning if they hand them over to government authorities. Officials in charge of this site should be more accessible. Because at the end of the day why would people protect something if they don’t know what they are protecting?

Chandraketugarh is a site that has more than what meets the eye, but that should not be the case. This article is not merely an attempt to bring out the historical importance of Chandraketugarh, because that would be falling in the same category of limitations seen in scholars and books of history. Rather, it is meant to suggest, brazenly, that beyond the borders of history lies a world replete with economic possibilities. That is, even if the many years of excavations and artefacts are buried under the jargon of specialists, the archaeological importance of the site is capable of providing the community around the site diversified means of livelihood. And this would only be possible if sites such as Chandraketugarh are given the respect and title of being a heritage site.

References

Lahiri, Nayanjot. 2001. ‘Destruction or Conservation? Some Aspects of Monument Policy in British India.’ In Destruction and Conservation of Cultural Property, edited by Robert Layton, et al. London: Routledge.

Further Readings

Davis, Richard. Lives of Indian Images. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997.

De, Gourisankar, and Subhradip De. Chandraketugarh: A Lost Civilization, vol. II. Kolkata: Sagnik Books,2006.

Chakrabarti, Dilip K. Archaeology in the Third World: A History of Indian Archaeology since 1947. Delhi: D.K Printworld Ltd., 2003.

———. ‘Monumental Follies.’ India International Centre Quarterly 33.

———. Monuments Matter: India’s Archaeological Heritage since Independence. Mumbai: The Mark Foundation, 2017..

Maite, Dilip. Chandraketugarh. Debalay: Chandraketugarh Museum,1984.

Ray, Achintyarup. ‘History on Sale’, Times of India, July 24. Online at https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kolkata/History-On-Sale/articleshow/9340570.cms (viewed on December 27, 2017).

Websites