Introduction

Grey-green in the background, the lofty Sihyachal ranges (part of the Deccan plateau) embrace the Queen’s Memorial in their protective arms. The elegant and graceful monument, draped in white, can be viewed from a distance on the road between Daulatabad and Aurangabad. This structure, more popularly known as Bibi-Ka-Maqbara, is the most conspicuous landmark of the city, underlining its historicity.

Maqbaras are Muslim qabars or graves and were more popular during the Mughal period. They were monuments erected to entomb bodies and preserve the name and memory of the dead. Over time maqbaras came to be associated more with the graves of religious figures or waliyullah who dedicated their life to religion. But in the later medieval period, especially during the times of the Mughals, they began to be constructed as tombs for members of the royal family.

Dilras Banu Begum

Bibi-Ka-Maqbara was erected in memory of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb’s wife, Dilras Banu Begum, popularly known as Begum or Bibi (often misinterpreted as Bibi or wife). In Urdu, the term Bibi is used for a woman of nobility, while Begum is a more reverential term for a gentle or generous woman. Dilras Banu Begum was given the title of Rabia-ud-Daurraini ('the modern-day Rabia'). The title refers to Rabia Basra (in Iraq), a generous lady who was known for her pious and kindhearted nature.

Bibi-Ka-Maqbara is situated in the historical city of Aurangabad in Maharashtra. As the Mughals had their capitals in Agra and later in Delhi, most of their notably grandiose and opulent memorials are found in the north. Bibi-Ka-Maqbara was one of the isolated Mughal monuments built in Maharashtra due to Aurangzeb’s long-term governorship of Aurangabad. Probably due to its unjustified comparison with the more celebrated Taj Mahal, it began to be referred to by some historians, travel writers and scholars as ‘Deccan ka Taj’, the ‘Poor Man’s Taj’, ‘Mini Taj Mahal’, etc. However, such comparisons denigrate this exquisite and picturesque shrine.

Controversy over the ownership of the Maqbara

The issue of the ownership of this refined memorial has been fraught with controversy. Historians and scholars as well as travel writers seem divided on this. Some have credited Aurangzeb with its creation while others have identified Mohammed Azam Shah, son of Aurangzeb, as being the one who commissioned the structure in memory of his beloved mother.

The Archaeological Survey of India’s information board displayed at the entrance to the site credits Mohammed Azam Shah with the building of this tomb. The Aurangabad Gazeteer (1997) as well as the book, Glimpses of the Nizam’s Dominion (Campbell 1898) attribute the monument’s creation to Azam Shah. Their contention is that Aurangzeb was averse to the building of monuments and hence there are very few significant structures belonging to his time. The few that Aurangzeb commissioned as per historical records are the white marble mosque in the Red Fort precincts in Delhi, the Badshah Mosque at Lahore and a mosque in Benaras (Srivastava 1964). However, Srivastava credits Aurangzeb with the building of the Maqbara for his favourite wife Rabi-ud-Daurrani. While Naseem supports this contention, she criticizes the monument’s inferior workmanship and execution, which she says is ‘half the size of the Taj Mahal and a mediocre production’ (Naseem 1993).

However, now with the support of factual historical data it is easier to arrive at some sort of consensus. As per historical records, Aurangzeb was married to Dilras Banu Begum, the daughter of Shahnawaz Safavi in May 1637 at the Agra Fort. This was during his first governorship of the Deccan which spanned 1636 to 1644. He came to the Deccan with his wife in 1637. In 1644 Aurangzeb’s sister Jahanara Begum met with an accident. When Aurangzeb and his wife heard about the mishap they immediately travelled to Agra without Emperor Shah Jahan’s permission. Shah Jahan punished his son for this delinquency by sending him to Kabul and Kandahar, considered in those days difficult and challenging regions (Kagal 1994). They were finally permitted to return to Agra in 1652, the same year that the Taj Mahal was completed. Both Aurangzeb and Dilras Banu saw the Taj and were impressed to such an extent that Dilras persuaded her husband to construct a similar edifice for her in Aurangabad with the Emperor’s permission. In the Mughal Raj a parwana or license was required from the Emperor for the transport of building materials such as marble or red stone from Makrana and Agra (Qureshi 2005).

The construction of the Maqbara was initiated in 1653 as confirmed by the accounts of the foreign traveler Jean Baptiste Tavernier. He writes that once during his journey from Surat to Golconda, in Aurangabad he saw more than 300 wagons laden with marble, the smallest drawn by 12 oxen and the largest by 20 oxen, from the maqbara built in the city in 1653 (Zaka-ul-lah 2013). As per most references, the Maqbara was completed between 1653 and 1660. When Monsieur de Thevenot, a French traveler, visited Aurangabad in 1667 he described the monument thus, ‘King Aurangzeb built a lovely mosque for his first wife whom he dearly loved and who died in this town. The mosque was covered with domes and minarets.’ This provides ample evidence that by 1667 the monument had been completed.

Again, as per recorded history, Dilras Banu had five children, Zeb-un-nisa, Zinat-un-nisa, Zabt-un-nisa, Mohammed Azam Shah and Mohammed Akbar. Mohammed Azam Shah, the fourth child, was born in 1653. The last son, Mohammed Akbar, was born in 1657 and Dilras Banu died during childbirth. Mughal records too confirm these dates. It is thus hard to imagine that a child of four could have commissioned the Maqbara. So why do so many scholars and historians continue to give credence to this theory? Perhaps, these claims may have arisen due to the fact that when Mohammed Azam was the governor of Deccan in 1680 he undertook intensive renovation work of the Maqbara (Srivastava 1964). This could be the reason that some travelers or scholars visiting the site mistakenly assumed that he had commissioned the monument. Be that as it may, it is definitely a major error that needs urgent correction. Surprisingly, despite being aware of the facts even the Archaeological Survey of India has not taken any action and rectified this blunder.

The designers and engineers of the Maqbara

Despite all these arguments and contentions, what is indisputable is the elegance and grace of Bibi-Ka-Maqbara. It is undoubtedly modeled on the Taj Mahal. It has simulated the Taj Mahal's style, pattern and design as it was conceived by Attaullah Rashidi, one of the three sons of Ustad Ahmed Lahori, the chief architect of the Taj Mahal, who had been given the title of Nadir-ul-Asar ('a rare gem of the period') by Shah Jahan (Naseem 1993). Attaulah gathered valuable experience while working under his father on the Taj Mahal. He was an expert in metal designing and also knew Sankrit and Persian. In fact, he translated Bhaskaracharya’s book on mathematics from Sanskrit to Persian (Rath 1970). Another person related to the construction of the tomb was Hanspat Rai whose name is engraved behind the metal door at the site. He was an engineer with technical expertise and was responsible for overseeing the construction of the entire structure. He also took decisions regarding the construction material and its use (Srivastava 1964). In all probability it was these two people along with Aurangzeb and his wife who selected the site for the mausoleum. This was a crucial decision as the site contributes immensely to the aesthetic elements of the architecture (Srivastava 1964).

Fig.1. View of the Maqbara with a hilly backdrop

The building needed to be constructed in a place with beautiful surroundings. The Mughals laid great emphasis on this aspect. The Taj Mahal’s grace can to some extent be attributed to its location on the banks of the Yamuna River. The same holds true of the Maqbara, whose beauty is enhanced by the velvety green hills that form a picturesque backdrop (Fig.1). In fact, the Kham River once flowed right behind the Maqbara. In later times the course of the river was diverted and it now flows through the city. Another major advantage of this Mughal structure was its setting on the most elevated part of the city, making it visible from a distance, which added greatly to its splendour.

The Gardens

Gardens were an integral part of the Mughal aesthetics. These were mostly geometric in design with layouts that had been developed in Persia and Turkistan (Naseem 1993). The first Mughal garden in India was commissioned by Babur at Agra and was named Hasht-Bihisht or Nur-o-Afshan. Most of the Mughal gardens are based on the Char bagh design. In this creation the garden is a four-fold plot consisting of a huge enclosure with four gardens. The chambers and water courses are paved with fine ceramic ware and are lined with cypress, pine and palm trees and also many beautiful flowering plants.

Fig.2. Garden around the Maqbara

The gardens of Bibi-Ka-Maqbara too are set out on the Char bagh design. In the Maqbara the specified land area is divided into four equal parts with the main building in the central portion of the garden (Kagal 1994) (Fig. 2). The complex is divided into four gardens with one building on each side (Fig. 3a and 3b). All four buildings are equidistant from each other. On the east is the Jamait khana or Aina khana (so called due to the mirrors fixed on its doorway) and on the west a mosque. On the north side is a Baradari (with 12 doors), while on the south is the main entrance which is a huge two-floored building (Fig. 4a and 4b).

Fig. 3a. Building on one of the side walls

Fig. 3b. Building on one of the side walls

The gardens once had lush green lawns and trees such as cypress, pine, palm, mango and Ashoka. Besides trees, beds of seasonal flowers and colourful roses too are planted. On either side of the pathways seasonal flowers and Ashoka trees have been planted.

At the centre of the pathways on four sides are oblong reservoirs, which are 488 feet long, 96 feet wide and 3 feet deep, with a total of 61 fountains (Fig. 5). The water comes through the slanting red stone or marble carved sheets connected to internal wells on all four sides of the central building (Kagal 1994) (Fig.6).

Fig. 4a. Main entrance, view from inside

Fig. 4b. One of the balconies of the main entrance building

At the entrance, on the south side, is a water pool, 18 feet x 28 feet. It is there on the other three sides of the complex as well, that is, in front of the Aina Khana, the Masjid and the Barradari. Besides this, the Maqbara also has several octagonal cisterns with 32 shafted pillar decorations in red stone. These are some of the most unique cisterns to be found in India.

Water sources

The water required for this huge garden complex, with its several water channels, was provided by various sources. It was supplied via underground water channels from Nahar-e-Begumpura, which is in close proximity to the Maqbara. Additionally, on the premises is a separate tank, which is called the Haathi Hauz on account of its huge size. This tank also distributed water to the oblong reservoirs, the tanks, etc. Water was also taken from the famous Nahar-e-Ambari, a water distribution system created by Malik Amber in 1617. In fact, a visit to many of the Mughal mausoleums makes one conclude that the Maqbara has a significantly high number of water devices like water chutes, tanks, cisterns and reservoirs, and can be compared to the beautiful Shalimar garden in Srinagar in this regard.

Fig. 5. Oblong reservoir at the centre of the pathway

Fig. 6. Slanting marble carved sheets for water to flow down

Unfortunately, over time the condition of these water devices has gone from bad to worse due to a number of reasons. For instance, the lime pipes that once provided water to the Maqbara are broken at many places due to uncontrolled construction work near the site. Consequently, the water that once flowed through uninterrupted now comes in spurts. Another cause for this is that for the past several years the entire region has been facing a water shortage due to scanty rainfall. Despite these problems, the ASI authorities have kept alive the gardens. However, due to insufficiency of water they have been unable to fill the tanks and reservoirs, hence, the fountains have all dried up.

Area of the Maqbara

The complete area within which the Maqbara is built is 15,000 square feet with each bagh measuring 500 yards by 300 yards. The entire area is fortified with high walls. There is a pavilion (chhatri) on each of the four corners of the wall. The cupolas are octagonal with eight pillars and the cupola roofs are supported on brackets and lintels. These were created by the Mughals not only for aesthetic effect but also to station security guards. The walls around are connected to each other via a wall walk, a common feature in most Mughal structures. Royal tombs were always protected by high walls and security guards and therefore the enclosure wall too is crenellated.

The main mausoleum

The principal building of the Maqbara, in which lies the Queen’s tomb, is at an elevation of 19 feet. Much of the Maqbara’s beauty and exceptional grace is attributable to this factor, as a majestic elevation creates an immediate impact on the beholder, just as it does in the case of the Taj Mahal. The main platform is 72 feet x 72 feet and the main mausoleum area 24 feet x 24 feet. The dome of this plinth, main chabutra and the octagonal minars on all four sides are made of marble (Fig. 7). The minars are 72 feet high and have 144 stairs leading to the top. They are three-storeyed and after each floor a gallery opens out with railings of red sandstone carved in jali design.

Fig. 7. Front view of the main mausoleum

In the main mausoleum, on the upper floor are marble jalis on all four sides, with a height of 7 feet and width of 6-7 feet. From here we can see the tomb of Rabia-ud-Daurrani (Fig. 8). There are staircases leading to the tomb, which is surrounded by exquisite marble screens with beautiful floral designs, which are octagonally shaped.

Fig. 8. View of the queen's tomb from the top

The symmetry of this elevated platform with its four minars was perfect till 1803, the year that the Nizam Sikandar Jah decided to transfer his capital from Aurangabad to Hyderabad. He was so captivated by the Maqbara that he planned to dismantle it and shift the structure to Hyderabad. The dismantling was actually initiated on the left side of the central structure. Fortunately, he seemed to have had some premonition of the damage that the structure was soon to face. He not only stopped the work and refurbished the demolished portion but also built a mosque as atonement on the left side of the Maqbara (Nath 1960).

Above the entire structure is a huge white dome with a brass pot finial and four smaller domes. Four lofty minarets with red sandstone pavilions stand freely at the corners of the terrace (Fig.9).

Fig. 9. The dome and the minarets

Decorative and ornamental elements at the Maqbara

From the entrance to the interiors various decorative elements are employed. Besides architectural and aesthetic elements like arches, domes, minarets, kiosks and architraves, these ornamental devices were used to add to the beauty and elegance of the Mughal structures. Even if at the Maqbara very rich elements like mosaic, inlay, glass mosaic, inlaid marble screens and pietra dura were not used, a few simpler and some highly ornamental decorative devices were used. Here we find that stucco painting, stucco plaster with relief ornamentation, stucco lustro and dado were used, besides glazed tiles and lattice work. Below are brief descriptions of some of these decorative devices.

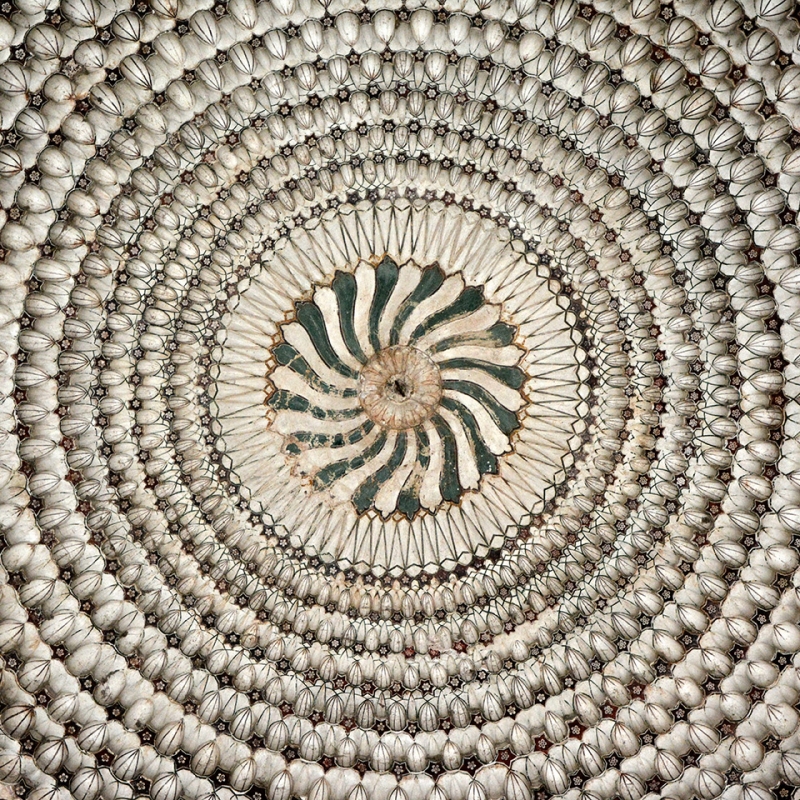

Stucco painting and relief ornamentation: Stucco is a slow-setting hydraulic lime plaster used on walls and vaults as a ground for relief ornamentation and fresco painting. At the Maqbara, as soon as you enter the main entrance gate you find instances of stucco painting. The patterns in stucco paintings are mostly geometric, floral, inscriptional and conventional. At the Maqbara geometric, floral and leaf designs are used. The main entrance ceiling has exquisite paintings of geometric designs that look as if they have been woven with intricate threads into a complicated design (Fig. 10).

Fig.10. Design on the ceiling of the main entrance building

Besides stucco painting, relief ornamentation is found in the main mausoleum on the exterior as well as the interiors (Fig.11). Designs of diaper (a pattern repeated continuously over the wall surface), lotus medallions, rosettes, and mehrab with floral and leaf patterns have been used inside.

Fig. 11. Relief ornamentation on the mausoleum

The relief designs are mostly of vase-foliage, depicting a Hindu kalash (pot) with a plant and floral patterns emerging out of it (Nath 1960). These can be seen on the exterior of the main wall of the Maqbara. At a few places the kalash and flowers are in high relief. These are bordered with floral patterns inside geometric designs. Similar floral designs can also be seen above the engrailed arch of the main Maqbara gate.

Stucco Lustro: Some of the paintings have been done with the help of hot iron tools. These are overlaid with wax or other similar material and polished. It is no wonder that a great number of polished surfaces with intricate designs are found here. Right from the entrance building to the main tomb, the dado design is frequently seen, where the lower portion of the wall is painted separately or as a separate compartment.

Jaliwork or Lattice Work: The lattice work here is mostly done on black or red stone except inside the main mausoleum where the tomb lies. Lattice work refers to intricate floral, leaf or geometric patterns that are carved out on screens (Fig.12a and 12b). At the Maqbara these screens are visible as you enter the main building and walk towards the tomb, with the oblong reservoir in the centre and tall cypress trees on either side, behind which are stone screens decorated with different designs. Inside the main tomb area is a marble screen with floral decoration.

Fig.12a. Jali work on the mausoleum

Fig. 12b. Jali work on the mausoleum

Glazed Design: At a few places glazed tiles too have been used to add to the beauty of the monument. Glazed tiling was an ancient technique used in Egypt and Mesopotamia, which the Mughals too used extensively. While painted colours fade after sometime, glazed tiles are more durable, and are dazzling in appearance. Though glazed tiles are found in abundance at Akbar’s Tomb, Jahangir’s Mahal and Itmad-ud-Daulah’s tomb, they have been used sparingly at Bibi-Ka-Maqbara with a few also being used inside the tanks, cisterns and the reservoir (Kagal 1994).

Metal Door of the Maqbara: The metal door at the entrance of Bibi-Ka-Maqbara is made of wood with a metal-plate cover. As the architect, Attaullah Rashidi, was an expert in metallurgy, he crafted a metal plate with geometric designs. There are star-shaped motifs with smaller stars within them interspersed with tiny rosette designs (Fig. 13). On either side of the central space are designs of creepers interspersed with ornamental leaves and rosettes. The central knob of the door is surrounded by a floral pattern within which are carved geometric designs with flowers, leaves and creepers. Around the knob, above the central flower, trellis work has been used. There is an inscription on the door mentioning that the Maqbara was designed and erected by Attaullah the architect and Hanspat Rai the engineer. Metal doorways are also carved on the main tomb with four smaller doors on all four sides, which have similar geometric and floral designs on metal plates.

Fig. 13

Brick designs on the footpaths: Even though the Maqbara has been referred to as a poor man’s Taj, the painstaking attention to detail on the part of its designers belies such criticism. Efforts were taken to beautify even the footpaths, especially in the interior areas, with decorations in various patterns. These have been crafted out of medieval bricks that due to the use of lime are still strong and in a good state of preservation.

Although at the Bibi-Ka-Maqbara calligraphy has not been used as extensively as at the Taj Mahal, one of the walls of the mosque on the west has the 99 names of Allah written in calligraphy. The decorative handwriting is a classic example of superior penmanship. The mosque also has an inlaid floor which resembles individual prayer mats laid alongside each other.

A comparative study of Bibi-Ka-Maqbara and the Taj Mahal

In practically every article on Bibi-Ka-Maqbara, whether in magazines, books, newspapers or various websites, there are inevitable comparisons made with the richer and more flamboyant Taj Mahal. While comparing these two monuments it is necessary to understand the difference in status, position, access to the royal treasury, supreme power and other advantages enjoyed by Shah Jahan while constructing the Taj, in contrast to the status, financial circumstances and political position of Aurangzeb.

Aurangzeb during this period was the governor of the Deccan and was required to raise his own revenue in his subedari, fight wars, confront enemies, maintain his large army as well as indulge any cultural passions that he had. Aurangzeb, in all historical records, was a dutiful and conscientious ruler who continuously contributed to strengthening the Mughal position and status through expansion. By waging relentless wars against the rulers in the Deccan he was adding to the glory of the Mughal dynasty. At the same time he had to face an internal antagonist in the form of his own brother Dara Shukoh, Shah Jahan’s favourite son, who not only despised Aurangzeb but was also jealous of his superiority as a powerful strategist with political acumen and decision-making skills. Dara Shukoh also had the advantage of residing with his father in the capital thereby influencing his father to take decisions against Aurangzeb. Against all these odds Aurangzeb and his wife Dilras Bano Begum built the Maqbara which despite the lack of ample finances is one of the finest and most imposing monuments in the Deccan region. Its grace, delicacy and finesse cannot be denied. Even from a distance the Maqbara does not fail to impress even the most sceptical visitor. But as acknowledged earlier, comparisons are unavoidable and hence will be dealt with point by point.

The following are the differences between the monuments:

The Taj Mahal is a capacious complex without direct access to the main structure. A visitor enters the Taj through the long row of arcaded red stone buildings flanking the double-arched gateway. In the inner enclosure is a rectangular space with courtyards, lawn apartments, out-houses, bazaars and stables for horses. There is a gateway towards the north with an entrance to the main mausoleum. The Maqbara though has direct access to the main mausoleum.

The Maqbara is 30 per cent smaller in size than the Taj Mahal.

An important departure from the Taj is the location of the Maqbara at the centre of the char bagh, while the Taj is located at the extreme end of the char bagh. Also, the Taj is at the centre of two structures, the mosque and a sarai, which serves to balance the main structure perfectly.

The Taj is constructed completely in marble, right from its entrance structure, which is a red stone entrance gate interspersed with marble. At the Bibi-Ka-Maqbara, except for the small central portion of the main mausoleum, the rest of the building is constructed in stone, red stone, lime and stucco plaster.

The dome of the Taj Mahal is more bulbous and rounded with four small kiosks around it, while the Maqbara’s dome is a little more vertical. The dome of the Taj is the crowning glory of the entire structure. In comparison, the Bibi-Ka-Maqbara’s dome seems a little crowded with four smaller domes and the four minarets.

The creators of the Taj used a tremendous variety of rich decorative ornamentation that lends it additional beauty and grace. This is visible in the quality of the finishing of the pietra dura work, the decorative effect of the bold scroll work, in the spandrels above the great arches, the perforated marble above the great arches, the perforated marble screens and the enrichment of each scroll with inlaid precious stones. This is surpassed by the pietra dura in the cenotaph. Diapers and borders of pendant flowers, decorative lilies, inlay work in gold on the marble screens, glass mosaic tiles, exquisite painting and relief work in stucco plaster and perfect calligraphy are some of its outstanding features. The Maqbara has less ornamental decoration. Its creators employed the dado design, intricate geometric patterns on the ceilings, stucco paintings and relief work, stone, red stone and marble screens, metal ornamentation, etc. Overall, it is far simpler and more austere in comparison to the Taj.

The main platform of the Taj is at a height of 22 feet while the Maqbara stands on a 19-foot plinth.

The Taj Mahal took around 22 years to complete while Bibi-Ka-Maqbara was completed in 7 years.

The main structure of the Taj is a square mausoleum 108 feet high with a cupola at each corner and a bulbous dome of exquisite grace and proportion at the centre rising to a height of 187 feet and towering above the surrounding cupolas. The minaret in each corner rises to a height of 137 feet. By way of comparison, the height of the minaret at each corner of the Bibi-Ka-Maqbara is just 72 feet and the height of the dome is 137 feet.

The following are the similarities between the monuments: both were built on the banks of a river, both were built on the char bagh design, and both were built in the memory of two gracious ladies who were known for their generosity, kindness and charitable nature.

Whatever their differences and similarities, in the final analysis, it is unjust to compare these two monuments. The Bibi-Ka-Maqbara has its own grace and dignity. It is the only monument erected by the Mughals in the Deccan and hence is referred to as the Taj of the Deccan. In the midst of a persistently dry climate, the Maqbara is like a balm to the eyes with its tall cypress trees, lush dark green lawns, huge mango trees and colourful rose bushes and seasonal flowers planted all around.

References

Campbell, Claude A. 1898. Glimpses of the Nizam’s Dominions. Bombay: C.P. Burrows.

Gazetteers Department, Government of Maharashtra. 1977 [1884]. The Aurangabad Gazetteer, ed. Munir Nawaz Jang (revised edition). Mumbai: Government Publication. Online here (viewed on April 3, 2017).

Kagal, Carmen.1994. ‘On Masjids and Maqbaras’. The Taj Magazine 23. 2.

Nath, R. 1970. Colour Decoration in Mughal Architecture. Bombay: Taraporevala Sons and Co.

Naseem, Waheeda. 1993. Malik Ambar Se Alamgir Tak. Aurangabad.

Qureshi, Rafat. 2005. Mulk-e-Khuda Tangneest. Delhi: Bharatiya Kala Prakashan.

———. 2016. Aurangabad Nama. Delhi: MR Publications.

Srivastava, A.L. 1964. Medieval Indian Culture. Agra: Shiva Lal Agarwala.

Zaka-ul-lah, Maulvi. 2013. Aurangzeb Alamgir. Delhi: Areeb Publications.