Though Ayurveda is widely known as one of the indigenous forms of medicine in India, its literal meaning is ‘knowledge of life’ or ‘knowledge of what promotes and what does not promote life’. It was regarded as a branch of Vedas (upanga) or as the fifth Veda (Panchama Veda) to indicate its sacred origins. All the four Vedas have references to health, long life and diseases, but the fourth—Atharva—abounds in hymns related to health and disease. In Maurice Bloomfield’s collection of hymns from the Atharva Veda, 65 relate to the cure of diseases, 10 to promoting good health and longevity, 25 against demons and sorcery, 33 for inspiring love between men and women, and nine on cosmogonic and philosophical themes (Bloomfield 2000). No wonder, Charaka exhorted the students of Ayurveda to be reverential to Atharvan teachings in their endeavors. An Atharvan hymn referred to ‘hundreds of physicians’ (Bhisak, Atharva Veda II 9.3) who seem to have been roving Vaidyas within easy reach of people. The roving tradition was strong as a branch of Atharva Veda was called ‘Charana Vyuha’ and Charaka, as his name implies, was believed to have been a member of the fraternity.

The practice of healing in the Atharvan period (1500 BC) was based on the belief that diseases were punishments decreed by offended gods such as Indra and Agni for human transgressions, and propitiatory hymns played the primary role in therapy while herbal formulations and rituals were secondary measures. In the absence of hymns, herbal formulations were regarded ineffective. The therapeutic efficacy of herbs was not due to pharmacological action because they were often believed to work when tied around the wrist of a patient as an amulet with an accompanying chant of chosen hymns. The Kaushika Sutra of Atharva Veda gives an outline of what medical treatment was in the remote past, combining holy chants, administration of herbal formulations, and rituals including tying of amulets, presided over by a respected Acharya or Vaidya. The Atharvan treatment of a disease was a far cry from the Ayurvedic treatment of the same disease as described in the Charaka Samhita.

Traditional medicine in Buddhist India

The Vedic phase was followed by another millennium in the history of Indian medicine, which was dominated by the reign of Buddhism. The school of Takshashila was already reputed as a physician's training centre in Buddha’s lifetime because Jivaka was an alumnus of Takshashila, who became the physician of the Buddha and of King Bimbisara in Pataliputra. Though the term Ayurveda was not used, many concepts, procedures and herbal preparations which found mention in Buddhist texts such as Milindapanho, Mahavagga, and Visuddhimagga were forerunners of what appeared in Ayurvedic classics later. Similarly, Jivaka was a pioneer in surgery, and Buddhist literature has several references to his skill in doing trephining of the skull, repair of anal fistula and other procedures. Leaders of healing in Buddhist India, Buddhist physicians transmitted Ayurvedic practice and training all over India even as far as Kerala. While the Buddhist ring is audible in the Charaka Samhita composed in the Kushana period (1st century CE), Vagbhata (6th century CE)—the last of the Great Three of Ayurveda (Brihatrayee)—was a self-proclaimed Buddhist. The most important change brought about by Buddhism in the Atharvan practice of medicine was minimizing, if not eliminating, the role of hymns in therapy.

Classical Period

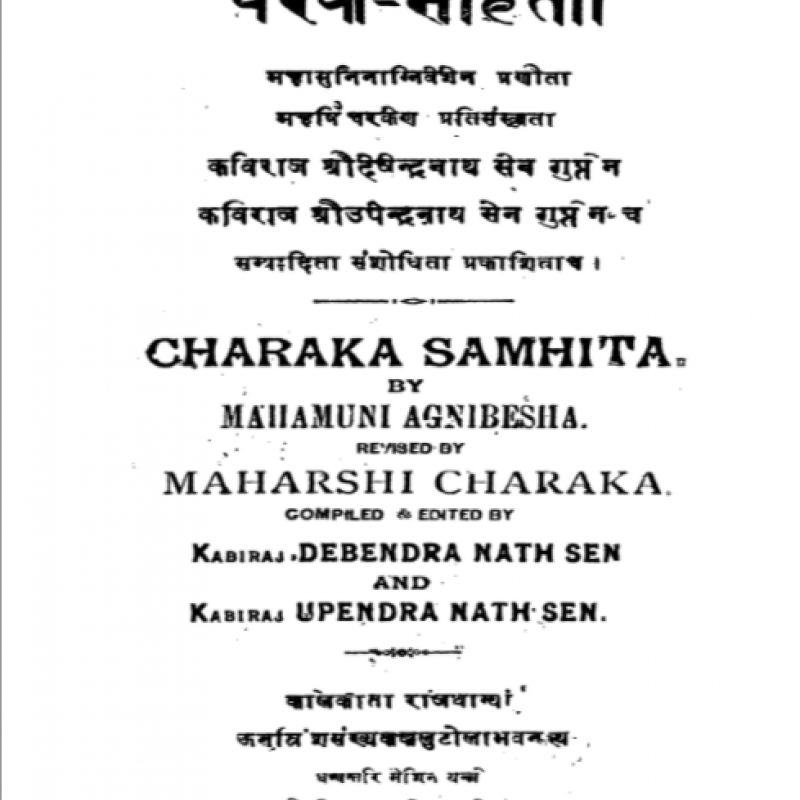

The Buddhist phase was followed by the classical period, marked by the advent of Charaka (1st century CE) who redacted the text of Agnivesha which had been the principal authority of Ayurveda in earlier centuries. Charaka’s redaction was one of the earliest texts to use the term Ayurveda and to present Ayurvedic concepts and practice against a background of philosophy and lofty ideals. As Charaka, in his own words, also sought to shift Ayurveda from faith-based (daiva vyapashraya) to reason-based (yukti vyapashraya) practice, his redaction of Agnivesha’s Tantra soon earned recognition as Charaka Samhita and the foundational text of Ayurveda. Sushruta Samhita was similarly redacted by Nagarjuna from an earlier text in the fourth century, which was more lucid and better structured than Charaka’s and had a markedly surgical orientation. Vagbhata was a native of Sindhudesha, whose classics—Ashtanga Samgraha and Ashtanga Hrdaya—appeared in the sixth century. They were based on the texts of Charaka and Sushruta, but were modified, restructured and simplified to suit the changed times (yuganurupa). Unlike the classics of Charaka and Sushruta which paid scarce attention to literary grace, Ashtanga Hrdaya of Vagbhata excelled as much in the concise restatement of Ayurveda as in the majesty of poetic composition. The classics of the Brihatrayee were never equaled in authority by any of the Ayurvedic texts which appeared in different parts of India in subsequent centuries.

The classical phase when the books of Charaka, Sushruta and Vagbhata appeared bore witness to the full development of the eight branches of Ayurveda and the peak of its achievement. Ayurveda spread throughout India; Charaka and Sushruta’s Samhitas were translated into Arabic for the Caliphate and its influence was felt in Central Asia as shown by the discovery of the Bower manuscript. As a major subject of study in Nalanda, Ayurvedic concepts traveled to Tibet, China, Korea and the rest of East Asia through Buddhist channels. Astanga Hrdaya was translated into Tibetan and taught even in the sunset years at Nalanda in the 10th century. Garcia de Orta’s ‘Colloquies on the Simples and Drugs of India’ based on his long experience in Goa as a physician in the 16th century drew the attention of European scholars and physicians to Ayurveda though the interest was largely focused on herbal remedies.

Stagnation

The classical phase began to fade after Vagbhata, when one hears no longer of masters on par with Brihatrayee, or of Takshashila or Nalanda which were destroyed. The social outlook became regressive as shown by new restrictions on the initiation of ‘non-twice born’ into Ayurvedic studies and the classification of even snakes on the basis of caste! The final blow fell when all those who did manual procedures and ‘dirtied their hands’ such as surgeons, weavers, blacksmiths, and other craftsmen were displaced in the social hierarchy and regarded as ‘lower castes’. As a result, the reduction of fractures, conducting deliveries, doing plastic repair of the nose, and all other surgical procedures were no longer done by Vaidyas but by illiterate men who transmitted their skill from father to son and were denied formal education and social mobility. Untrained and unable to answer the question 'why' in their varied operations, the practitioners became incapable of innovation, and the ancient procedures of Sushruta such as plastic repair of the nose and couching for cataract survived precariously as ancient relics in the fringes of Indian society when the British observers noted them in the 19th century. Ayurveda received little support from the state during the centuries of Islamic rule and faced disparagement by the colonial administration. From Vagbhata to the freedom of India, it was a long phase of stagnation for Ayurveda, when only limited advances were made such as the introduction of mercury and advent of rasashastra, use of pulse in diagnosis, and the description of syphilis, but the springs of originality had run dry.

Branches of Ayurveda

The eight-fold division of Ayurveda was outlined by Sushruta as follows (Sushruta Samhita Sutra 1:8):

1) Surgery (Shalya): Removal of foreign bodies; complicated delivery; use of cautery; setting of fractures; surgical instruments; surgical procedures, etc.

2) Diseases of head and neck (Shalakya): Diseases of eyes, nose and mouth

3) Internal Medicine (Kayachikitsa): Systemic diseases such as fevers, bleeding disorders, diabetes, insanity, seizures etc.

4) Diseases caused by supernatural forces (Bhuta vidya): Illness in children and adults, which do not conform to clinically identifiable patterns

5) Children’s diseases (Kaumarabhrtya): Health care of children; breast feeding, nutrition, diseases caused by evil spirits

6) Poisoning (Agada tantra): Bites by snakes, poisonous insects, rats, countering of poisons

7) Rejuvenant therapy (Rasayana): Promotion of long life, enhancement of physical and intellectual prowess; improvement in complexion

8) Enhancement of sexual potency (Vajikarana): Enhancing erectile function; improvement of fertility; treatment of seminal disorders

Basic Concepts

The eight-fold system of Ayurveda was built on the foundations of basic concepts and doctrines which were most clearly enunciated by Charaka. He was greatly influenced by the vibrant intellectual climate of his time, when the six systems of Indian philosophy—Samkhya, Nyaya, Vaishesika, Yoga, Mimamsa, and Vedanta—were in the process of differentiation and had found themselves locked in vigorous debates with Buddhist doctrines. Charaka was not only influenced by the philosophical currents around him but in turn influenced them to such an extent that S.N. Dasgupta argues the original Samkhya—prior to Isvara Krsna—should be credited to him (Dasgupta 1992:216). He adopted the Vaishesika classification of gunas (qualities) in his description of categories but changed the connotations of certain terms (e.g. samanya/vishesha) to suit the contextual requirements of Ayurveda. It was a tribute to his genius as a philosopher–physician that he could integrate lofty philosophical thoughts with the endeavour of medicine. Ayurveda stands in relation to its fertile philosophical background as the central theme in the foreground of this great painting. Divested of the background, Ayurveda would be reduced to no more than a form of medical treatment. Two doctrines each from the physical and philosophical domains which enliven the background of Ayurvedic medicine are outlined here for illustration.

Five elements (Pancabhuta) (Sushruta Samhita Sutra 1:53): The human body is made of constituents (dhatus) evolved from five elements (bhutas) which also constitute the universe. These elements are space (akasha), air (vayu), fire (agni), water (ap) and earth (prthvi), which are homologous with the substances comprising the body. The homology between substances which constitute the body and the universe implies that they interact constantly and their levels fluctuate within a range between excess and deficiency. Maintenance of body constituents within the range is called equilibrium of constituents (dhatu samya), which is an essential aspect of good health. When the range is breached the result is disequilibrium of elements (dhatu vaisamya) or ill health. Apart from its pathophysiological significance, the panchabhuta doctrine has a bearing on Ayurvedic therapeutics. Food, drinks, and medication consist of substances which belong to the external world but at the same time are homologous with body constituents. When the reduction or augmentation of certain body constituents are called for in a patient during medical treatment, the rules of Ayurvedic therapeutics required a physician to prescribe food, drinks and formulations with properties opposed to those of the target substances in the body. This could not be done unless the substances within and from without the body were homologous and were able to interact.

Ayurveda sought the pancabhuta doctrine to reinforce its grand view of the universe as macrocosm and man as the microcosm. Universe and the individual were a seamless continuum and the individual was no more than a cosmic resonator.

Evolution of the universe (Parinama): Charaka’s analytical mind went beyond the homology between the universe and human body, and focused on the evolution of the universe—a subject which had been studied and debated in India for centuries and was dear to Sankhya philosophers.

Dasgupta argued that the main features of evolution according to the Sankhya interpretation of Charaka were very similar to those of Pancashikha in the Mahabharata (Dasgupta 1992:216). According to him, this was the original doctrine of evolution (mulasankhya) which antedated the scheme of evolution presented by Ishvara Krsna in the Sankhya Karika. It admitted 24 categories in the evolutionary sequence of the universe unlike the later Sankhya (Uttara Sankhya) of the Karika which postulated 25 categories. The process of evolution which began in an undifferentiated state of existence (avyakta) by a perturbation of the latent forces of rajas (firmament, dynamism) and tamas (inactive, entropic), went through sequential steps until it unfolded as the manifold components of the (indriyarthas) universe. Unlike Darwinian evolution which was open-ended, Charaka’s version of Sankhya held that the universe in all its immense diversity would return to the original undifferentiated state, and the cycle of differentiation and dedifferentiation would go on endlessly without the intervention of an external agent.

Destiny (Daiva) (Charaka Samhita Vimana 3:36–38): Confronted by suffering and death among patients, no sensitive physician could turn away from the human condition and the role of destiny. The traditional view in India held that fate (daiva) was supreme and no human effort could make the slightest difference to its inexorable operation. However, another view in ancient India known as pauruseya urged that the heroic endeavour of man could indeed alter the course of human destiny. This view was championed in the Yoga Vāsiṣṭha. Charaka took a middle position in this debate and argued that if predestination was carried to its logical conclusion, human effort including the physician’s endeavour would become futile. While acts of great evil could not admittedly escape karmic consequences, he noted that the bulk of what one does everyday lacked a moral content in so far as it relates to the business of daily living. He pointed out that if an individual chose to remain well by giving attention to hygiene, nutrition and appropriate conduct, it could not be claimed that his consequent well-being had been pre-ordained. Errors in judgment and conduct were amenable to prevention or correction by adherence to a code of proper conduct, which eschewed the overuse, under-use, or misuse of sense organs including the mind. While Ayurveda conceded that the role of medicine was no more than to give a helping hand to one mired in disease, to lift them out of the quagmire (Ashtanga Hrdaya Uttara 40:64), it never encouraged the passive acceptance of destiny. Vagbhata went beyond Charaka and declared, ‘Know ye, human effort can indeed overcome fate’. (Ashtanga Hrdaya Sarira 1:36)

Imprudent conduct (Prajnaparadha) (Charaka Samhita Vimana 3:4–16): Often humans fall victim to temptations even when they are known to be harmful. Smoking, alcohol, tobacco and many other substances are known to be addictive and dangerous but people get drawn to them as if they are pulled by an unseen and powerful force of attraction. This species of behavior arising from temptation and error of judgment was termed imprudent conduct (prajnaparadha) in Ayurveda, which figured prominently as a factor in the causation of diseases. According to Charaka, the human being is engineered by nature to be healthy and happy but imprudent conduct drives them to avoidable and even fatal diseases (Charaka Samhita Sutra 28:34–35). Many of the ‘lifestyle diseases’ of our time would be regarded by Ayurveda as the wages of prajnaparadha. The treatment of such diseases would demand self-control, changes in life style and individual transformation more than medical measures.

These examples illustrate the many basic concepts in Ayurveda, which include dosha-based constitution of human beings, dual approach in the non-suppression and suppression of physical and mental urges, living in accordance with the seasons, human conduct leading to the destruction of habitat and so on. Charaka Samhita concluded with the confident statement, ‘What you find here, you may find elsewhere; what you do not find here, you will find nowhere’ (Charaka Samhita Siddhi 12:52–54).

Physician’s training and ethics

Training of physicians took place in Gurukulas or in established centres of learning such as Takshashila and Nalanda. It is curious that the centres of learning are discussed in Buddhist literature but are not even mentioned in the classics of Brihatrayee! Jivaka’s training in Takshashila gives a vivid picture of institutional training in medicine in Buddha’s lifetime (Hardy 2010:238–249). The Gurukula system was more widespread and resistant to destruction from outside forces unlike major centres such as Takshashila which were vulnerable. The selection of pupils for training was based on physical, intellectual, behavioral, educational and caste criteria; the teachers too were obliged to possess high qualifications in terms of knowledge, skills, experience, and ethical conduct. Training was theoretical and practical because training limited to one segment made the trainee ineffective ‘like a one-winged bird’ (Sushruta Samhita Sutra 3:50). Theoretical training involved learning by rote, discourses and above all, discussions on specific topics by pupils under the supervision of the teacher. Charaka Samhita abounds in such discussions which were free, vigorous and interesting. Practical training involved assistance during domiciliary visits, examination of patients, collecting of herbs and preparation of formulations. Surgical training included cadaveric dissection, experimental surgery in models (Sushruta Samhita Sutra 9:4–6), and apprenticeship under a surgical teacher. Following training, a physician had to obtain a royal license to start practice on their own. (Sushruta Samhita Sutra 10:3)

Professional ethics: In ancient India, a pupil was required to take an elaborate oath administered by the teacher before an academic assembly with fire as witness in an initiation ceremony. This took place at the commencement of training and covered their entire range of conduct including their obligation to the patient, to the teacher, to life-long learning, to learned individuals, old people, ascetics and all living creatures. The oath admirably sets forth what continues to be valuable in a physician’s professional ethics even today (Sushruta Samhita Sutra 1:2, Vimana 8:13).

Diseases and treatment

Diseases: The classics of Charaka, Sushruta and Vagbhata are encyclopedic in listing diseases and indicating their treatment. The descriptions are systematic in so far as they deal with causation, clinical features, diagnosis, clinical course, prognosis and treatment including that of complications. The Charaka Samhita lays greater emphasis on internal medicine while Sushruta Samhita, though a general text, is conspicuous for its surgical orientation. Vagbhata’s Ashtangasamgraha and Ashtangahrdaya, especially Hrdaya, are based on Charaka and Sushruta but revised to suit Vaidyas of a later period when they were more interested in the practice of medicine than in philosophical reflection and basic doctrines! There are specialised texts (tantras) in Ayurveda for eye disease, diseases of animals and trees, and others. Diagnosis received priority in Ayurveda. P. Kutumbiah observes that Charaka’s description of diagnosis was the most comprehensive and complete in any ancient medical literature in the world (Kutumbiah 2003:90). In a preliminary assessment of patients, physicians would look into 10 factors including their own competence to treat the condition, availability of appropriate drugs, derangement of particular doshas (body humours), objective of treatment etc. (Charaka Samhita Vimana 8:68–74). This was followed by a second level examination (Charaka Samhita Vimana 8:96–122), which focused on 10 body features including prakriti, measurement of body parts, mental status, digestive power, exertional capacity, etc.

The third level of examination in establishing a diagnosis consisted of a synthesis of information gained from perception of clinical features employing the physician’s senses except taste, process of inference, and the authoritative teachings of saintly physicians rich in experience. The diagnosis did not stop with the identification of a disease and the underlying perturbation of doshas but also involved the determination of the stage of the disease. Before initiating treatment, a physician was obliged to examine whether the disease was curable, curable with difficulty, or incurable and whether any fatal signs (ristas) were present. Great importance was attached to prognosis.

Treatment: The aim of treatment was the restoration of the state of equilibrium of body constituents (dhatus); of fires (agni) which burn constantly in all constituents and make things happen; and of special products of digestion (doshas) by fires in the stomach and body constituents, without which no diseases could occur. For the treatment to succeed, a medical quartet had to be in place with necessary qualities, composed of a physician, attendant, drugs, and the patient. Treatment had to start in the early stage of a disease lest a late start in the advanced stage become risky or fatal. A basic principle of treatment was the choice of lifestyle, diet, procedures and medications with properties opposed to those of the deranged doshas in the patient. In mild derangements, simple measures (shamana) consisting of rest, fasting and reassurance would suffice.

However, if the disease was serious or advanced and derangement of doshas more severe, treatment would be stepped up to include, besides bed rest and a carefully selected dietary regime, an array of six procedures to be used singly or in combination (shodhana). These were lightening (langhana, reducing the body mass), building (brmhana, adding to the body mass), roughening (ruksana, drying up), lubricating (snehana, softening, smoothing), fomenting (svedana, inducing sweat, relieving stiffness), and arresting (sthambhana, arresting the flow in body channels such as binding bowel movement).

In dealing with certain conditions, the physician would also prescribe five procedures to rid the body of accumulated toxins and doshas (Ashtanga Hrdaya Sutra 17:29). Widely known as pancakarma, they were also employed during change of seasons to help the body adapt to the extremes in weather and as a tonic to enhance the sense of well-being. In pancakarma, the subject would be prepared by the administration of oily substances (snehana) and body fomentation (svedana), which were believed to mobilise accumulated toxins from countless channels in the body (srotas) and release them into the gut. This would be followed by inducing emesis and purgation or enemas to expel the toxins through the mouth or rectum depending on whether the disease had assailed the upper or lower half of the body. If the head was the seat of disease, expulsion of toxins was carried out by nasal purging (nasya). In vogue in Buddha’s period, these procedures continue to be used widely even today.

Materia Medica

The vast formulary of Ayurveda was divided into products of vegetable, animal, and metal/mineral origin. Plant products claimed over 75-80 per cent, animal products 10-15 per cent, and metals/minerals less than 10 per cent of total. The drugs were believed to produce their therapeutic effect through three intrinsic properties and one external factor. The intrinsic properties were taste (rasa) which was the equivalent of a chemical indicator at a time when chemistry was not born; potency (virya) which caused bodily effects such as emesis and purgation; and the taste of the drug after the initial phase of digestion was over (vipaka, Charaka Samhita Sutra 26:48–56). When certain drugs or even external applications produced extraordinary effects, independently of the three properties, it was attributed to prabhava (unique effect above and beyond its qualities). The prescription of appropriate treatment was a task which called for clinical acumen and long experience on the part of the physician.

The herbal formulations of Ayurveda constitute a vast national resource as it grew steadily from the time of Charaka or earlier by the gradual addition of new formulations or modifications of old formulations by later authorities, and the absorption of time-tested products on the basis of local experience from different parts of the country, as Ayurveda extended all over the subcontinent and beyond. Research on herbal products has claimed priority in investigative Ayurveda.

Whenever a patient’s condition required surgery such as fracture, abscess, ulcer, foreign body, lumps, etc., the standard practice was to refer him to the Dhanvantari division for treatment. The division of practice into surgery (Dhanvantari) and medicine (Atreya) existed even in the remote past of Ayurveda.

Ayurvedic view of life

Those who regarded Indians as a fatalistic, world–renouncing and passive lot of people dismissive of affluence and the good life would be surprised on reading the classics of Ayurveda. Listen to Charaka:

A person with a normal share of strength and combativeness, who is of sound mind and concern for things here and hereafter, is moved by three desires. These are the desire for life, for wealth and for life hereafter. The desire for life comes first, because the loss of life amounts to the loss of everything. To ensure good life and health, the observance of a code of conduct is necessary, just as careful attention needs to be paid for the proper care of illness. The pursuit of wealth comes next, because wealth takes second place only to life. There is scarcely anything more miserable than a long life without the means to live. One should therefore work hard to make a living by engaging in farming, animal care, trade, service and similar occupations. The third desire concerns life in another world after death, which does indeed raise many doubts. (Charaka Samhita Sutra 11:3–8)

The code prescribed by him for a long and healthy life was a far-cry from asceticism. It laid great stress on personal hygiene, nutrition and diet, elegant attire and ornaments, warm social relations, physical activity, pleasant walks in agreeable company, sexual enjoyment and all other aspects of a joyous and happy living. While he upheld the virtues of truthfulness, fearlessness, diligence, modesty, courage, forgiveness, and kinship toward all living beings, he placed no bar on the celebration of life and the use of rejuvenating drugs to enable one to live for a hundred years. Indeed, separate chapters were devoted in Ayurvedic texts to rejuvenating therapies (rasayana) and enhancement of sexual prowess (vajikarana). Vagbhata had a section on the erotic to embellish his chapter on vajikarana! (Ashtanga Hrdaya Uttara 40:35–47)

The detailed account of food and drinks, protocol for dining, lifestyle suited to different seasons, enjoyment of wines and a wine party which are found in Ayurvedic classics give the reader a flavour of the average Indian’s social life in ancient India. In seeking to live for a hundred years in good health and affluence, they were harking back to the Indian sages whose fervent prayer was to live ‘sound in limb and body to enjoy the divinely ordained term of life’. While Ayurvedic sages displayed unalloyed zest for a good and happy life, they never failed to emphasise the pre-eminence of ethics in all forms of human conduct. According to them, a good and happy life was inconceivable in the absence of righteous conduct (Ashtanga Hrdaya Uttara 40:35–47). Therein lies the secret of the uninterrupted practice of Ayurveda for over 25 centuries and its resurgence in recent times.

References

Bloomfield Maurice. 2000. Hymns of Atharva Veda. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Dasgupta, Surendranath. 1992 [1922]. History of Indian Philosophy, vol. 1. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Hardy R.S. 2010 [1860]. Manual of Buddhism. London: Williams and Norgate.

Kutumbiah P. 2003 [1962]. Ancient Indian Medicine. Chennai: Orient Longman.