There are many books and listings of fantastic architectures around the world, unfortunately, not many mention the Indian Nek Chand, writes Prof B.N. Goswamy. His Rock Garden in Chandigarh is as much a testament of architectural fantasy as Antonio Gaudi or Simon Rodia. (In pic: A display at the Rock Garden in Chandigarh, designed by Nek Chand; Photo courtesy: Ian Brown/Flickr)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh under the title ‘Architects and Fantasies’, and is reproduced here with permission.

The straight line belongs to Man. The curved line belongs to God . . . There are no straight lines or sharp corners in nature. Therefore, buildings must have no straight lines or sharp corners.

— Antoni Gaudi (1852-1926)

His (Antoni Gaudi’s) imagination burnt holes through the musty pattern books. His gift was an amazing capacity to imagine a building and then transform it into reality.

— Gijs van Hensbergen

A long time back, when in the U.S., I had picked up a copy of a book the sheer title of which attracted me. Fantastic Architecture it was named, with the sub-title: Personal and Eccentric Visions. Edited by three scholars from different but related fields, it was published by the prestigious house of Abrams. I naturally anticipated that it would go into elaborate details of the work of Antoni Gaudi, the great Spanish architect, or concentrate on something like the Watts Towers in Los Angeles: things that had over the years acquired iconic status as far as ‘fantastic architecture’ goes; but what I was really looking for in the book was an essay on the work of Nek Chand, our own icon of this field in India. There was nothing: not even one word, not a single photograph. I felt let down, even a bit angered. But I hung on to the book, for it did contain some other, very interesting writing and visuals. And from time to time I would dip into it, without my heart being in it because the absence of Nek Chand always irked me.

This time, a few months back when in was in the U.S. again, I chanced upon the same book in a shop. It looked a bit different: the cover was different, and the size visibly larger: apparently a new edition. But, to my utter amazement, and despair, still not even the barest mention of Nek Chand. I thought that at least by this time, when the revised and expanded edition of the original book was being planned, they would have learnt something about our man here, who had also had his unique ‘personal and eccentric vision’. Why was he not there? What could it have been then? Ignorance? The View of the World according to the West? Who knows? The opening paragraph of the introduction to the book read: “Architectural fantasy manifests itself in many ways. It is often spectacular; but it is not easy to categorize and analyse. Perhaps that is what fantastic means: to be so exciting or strange as to be indescribable.” True, but surely as applicable to Nek Chand’s fantasy as to that of those on whom the book concentrates.

Also read | Visual Landscape of Jainism in Early Modern Bengal

To get back to the theme, however, despite my reservations about the scope of the book. There are extraordinary visions recorded in the collection of images in this book, and one needs to get close to them: fanciful structures and gardens, castles and towers, materials that one would hardly ever associate with architecture. Within its covers, one meets George Plumb from Canada who ‘composed’ bottles of all kinds, shapes and sizes, into structures, and built a whole castle of glass in 1963. One runs into Fred Smith of Wisconsin who constructed a concrete park with 203 glass-covered concrete images, using also bottles and plastic. Juan Gorman, the Mexican, appears, having built his house on a volcanic rock formation, with a grotto in the lava rock turned into a living room covered with mosaics representing jaguars, condors, Mayan serpents and Aztec warriors. As major a figure in modern art as Nike de Saint Phalle of France who constructed countless giant ‘inflated’-looking sculptures comes into reckoning because of the house she built for an industrialist in Belgium, keeping her original ‘Nana’ — large female nude figure — in mind.

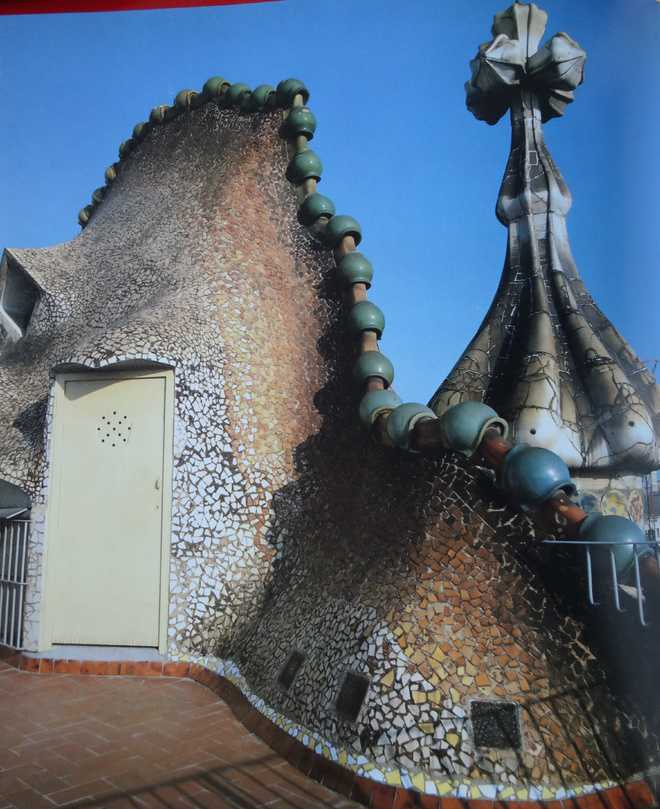

Quite naturally, the name of that Spanish genius, Antonio Gaudi, who is often seen as the High Priest of fantastic architecture, figures prominently here. The great structures that he put up, including of course the Church of the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, are now covered by the patina of time and adulation. The Church, built as an act of piety by the Catholic architect, was, in its own times (the 1880s), and continues to be, awe-inspiring, as much due to its scale as its daring: exuberant, whimsical, devout, amazingly innovative; truly a monument beyond compare. There was magic in his work: he was able to make ‘iridescent tiles recall the foam of a breaking wave’, turn the ‘ironwork of the balconies look like masks’. He also had the courage to make a roof appear like an enormous ceramic dragon with its scaly feet hanging over the eaves. Why? Because it symbolises St George, the patron city of the city of Barcelona.

Finally, but by no means the last in this long and absorbing list of men and women who dreamed different dreams, there is Simon Rodia who one needs to get to know: night guard, construction worker, layer of tiles, but also the man who, having come from Naples, started building, around 1921, on a triangular piece of land he had bought in Los Angeles, what came to be known as the Watts Towers. All an amazing structure made with bent steel rods, covered with cement inlaid with mosaic tiles, small pieces of glass and pottery, shells, and sometimes whole bottles.

Also see | Hafta Bazaars of Delhi

Incidentally, the city of Los Angeles at one time wanted to demolish the Towers but a committee of enlightened citizens fought to save it. Does this remind anyone of anything closer to home? Nek Chand’s Rock Garden which was under threat at one time, for instance?

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.