One finds a great deal of natural history drawings in Mughal paintings. Here, Prof B.N. Goswamy writes about Botanicum, a book that reminds us how plants appeared on Earth, and how we, in India, have lost the tradition of natural history paintings. (Photo courtesy: The Tribune)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh and is reproduced here with permission.

Nobody knows for certain how many species of plants there are. So far, scientists have counted about 4,25,000, but more are being discovered every day….Understanding these patterns of plant diversity is crucial to preserving all other forms of life on Earth, including us. Because without plants there would be no humans. Plants create and regulate the air we breathe … [While studying them, there are questions to be asked.] How did Earth reach the diversity and variety of plant life we see around us today? What did the first plants look like? When did the first forests form? When did plants first produce flowers?

— Prof. Kathy Willis, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Even though they are everywhere—plants, that is—living on almost every surface on Earth, “from the highest mountains to the lowest valleys”, as we read, “from the coldest and driest environments to some of the hottest and wettest places on our planet”, I have never been the one for botany. The only brief brush I had with the subject was at school when we had, as a part of our syllabus, the ‘ilm-e-nibaataat’, as the science of botany was called in Urdu. But, this said, I have always been drawn to natural history drawings, especially those of plants. Everyone, or nearly everyone, knows about the interest of the great Mughals in natural history studies, including, of course, those of flowers, of the kind which that wonderful painter, Ustad Mansur, produced for his royal patrons. Again, possibly everyone knows of the superb botanical studies that ‘Company painters’ like Sheikh Zayn-al Din and Bhawani Das turned out for discerning East India Company patrons towards the end of the 18th century. These works I know, of course, but I also know that the tradition of natural history paintings, at least in our own land, has been all but lost.

My interest in images of this kind was kindled again recently, however, when I came upon a volume that someone kindly brought as a gift for my little grandson. Botanicum is how the volume was titled, and its superbly designed cover I—even though it was not intended for me—found hard to resist. I sat down, almost ahead of my grandson, to dip into the book and found in it, apart from the highly informative text it contained, some exquisitely done illustrations by Katie Scott: created with pen and ink and coloured digitally. Not surprisingly, the book was a production of the Kew Gardens—that famous botanical garden in southwest London, which houses the “largest and most diverse botanical and mycological collections in the world”—and is now a World Heritage Site. I had visited the place years ago, but did not, for want of proper attention I am sure, realise that on these premises were preserved seven million plant specimens, and that in its illustration collection were more than 1,75,000 prints and drawings of plants. From the Kew—a part of the officially designated Royal Botanic Gardens—have also been emerging a whole slew of publications. Botanicum, which I was looking at—a virtual museum in itself—was just one of them.

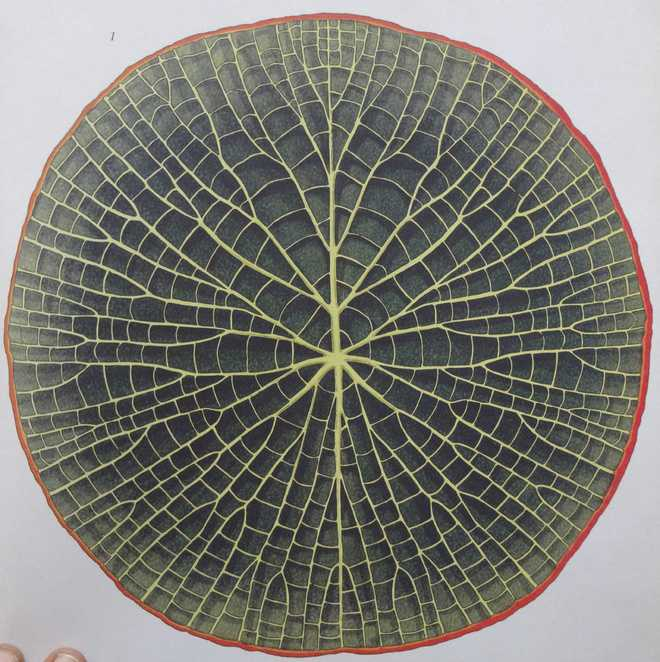

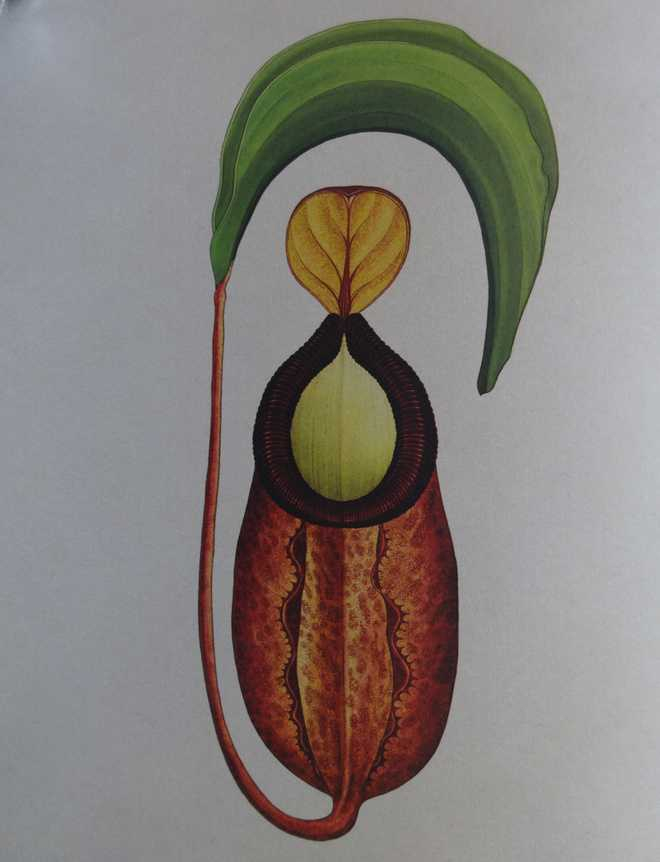

The book is most imaginatively organised, for the reader is taken in hand and led, step after step, ‘gallery after gallery’ as it were, through the world of plants. Brief but chiselled introductions take us through sections: ‘The First Plants’, followed by ‘Trees’, which are succeeded by ‘Palms and Cycads’, ‘Herbaceous Plants’, ‘Grasses, Sedges and Rushes’, ‘Orchids and Bromeliads’, and so on. Each section is densely populated. In the ‘First Plants’, one is introduced to things like algae, fungi, lichens, mosses and ferns, for instance; in ‘Herbaceous Plants’, figure the structure of flowers, bulbs, below-ground edible plants, vines and creepers. This is the way one proceeds, walking slowly through the book, but all the time, on practically every page, getting arrested by the sight of visuals: objects seen from the angle of maximum visibility, crisply drawn, precisely coloured. Completely consciously, the reader’s excitement is kept up. When we get to the section dealing with aquatic plants, to take an example, we are brought close to the amazing ‘Amazon Water Lily’, a waterborne plant with huge leaves that grow to over eight feet across and are so buoyant they can easily support the weight of a small child of up to 45 kg! Even a brief history of how Europeans discovered this ‘vegetable wonder’ in South America in 1837 is given. We are told of how the discoverer, Robert Schomburgk, managed to bring a specimen back to England, packing a bud and a small piece of the leaf in a barrel full of salt water. The section on ‘carnivorous plants’ focuses mainly on how plants catch and eat live prey—mostly insects, mites and spiders—in their need for nitrogen, but, in this very list, we also come upon the ‘Rajah Pitcher plant’, found on the tallest mountain in Borneo, which grows to a height of 10 feet, has a pitcher the size of a rugby ball, and is reputed to trap rats.

With clear intent, we are taken in the book both forwards and backwards. We are, as we need to be, reminded of how the earliest plants appeared on the Earth around 3.8 billion years ago. But we are also told, in no uncertain terms, that “the journey goes on”. For not only are scientists “continuing to discover new plant species every year (almost every day)”, but all this while “plants are continuing to evolve in response to changing conditions and new challenges”.

“The story has just begun”, a section concludes.

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.