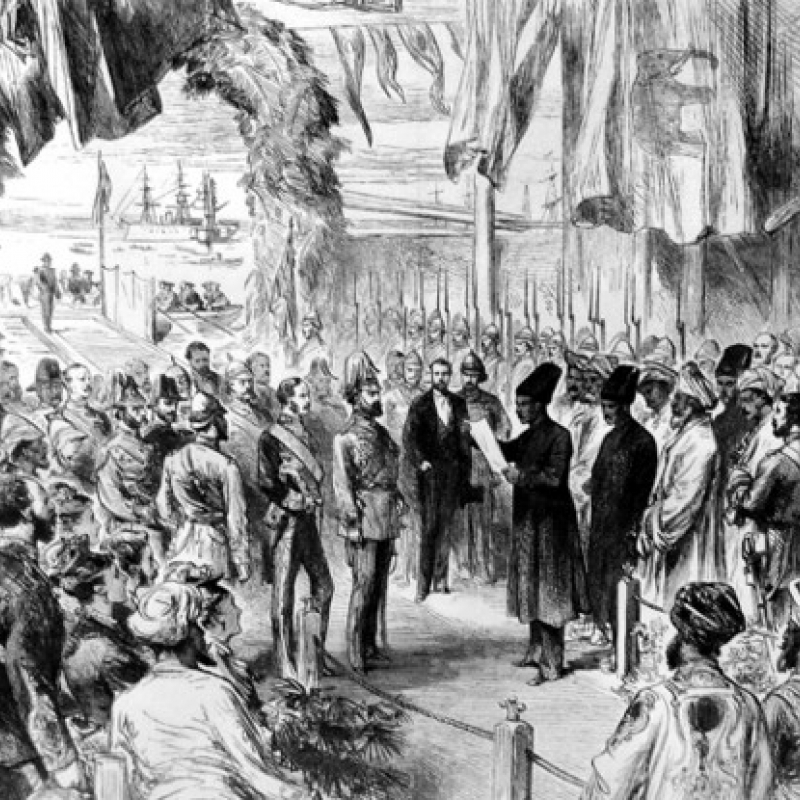

Back in 1875–76, the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII, came on a tour of India. As a preparation, he had begun to learn about India through acquainting himself with Indian artefacts. His extended tour added to that collection with gifts he had received. Prof. B.N. Goswamy writes about the displays looking like ‘a scene from the Arabian Nights' when it was exhibited at the Queen's Gallery in London. (In pic: Dosabhai Framji reading a welcome address to the Prince on behalf of the Bombay Corporation; Photo courtesy: The Tribune)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh, and is reproduced here with permission.

In the glittering Queen’s Gallery in the Buckingham Palace in London, two exhibitions, side by side, were on view—A Prince’s Tour of India, 1875–76; and Eastern Encounters. The former was a visual record, with objects and documents, of the four-month long diplomatic tour of India by the then Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII; and the latter a show essentially of Indian paintings and manuscripts in the Queen’s collection. The opening was strictly by invitation but, having received one, I went and spent quite a lot of time, looking and absorbing, taking things in. Looking back, at least three things I was immediately struck by: the quality of the objects on display which was outstanding; the distinguished crowd which came, consisting almost entirely of Britons of all ages, deep interest written on their faces as they went around, taking things in, like me; and the sharpness of understanding, the crispness and precision, reflected in the information panels, ‘didactics’ as they are called. One does not see this combination of things all too often.

A bit later—courtesy of the events co-ordinator—I received copies of the catalogues of both the shows, and am proceeding to write here of one of them—the other might follow—that covering the Prince’s Tour. In part, I imagine, because suddenly, reading about the Tour, I was reminded of an entertaining Urdu poem that I had heard in childhood, speaking of another princely tour, that of the third son of Queen Victoria, the Duke of Connaught to India in 1921. ‘Dilli darbaar ka jalwa’ [The glory of the Dilli Durbar] is how it was titled, describing a wide-eyed visitor’s observations. 'Hazrat Duke Kannaat (Connaught) ko dekha,' it began I think, and continued; 'Qutub Sahib ki laat ko dekha/ gorey dekhey, kaale dekhey, paltan aur risaaley dekhey, band bajaane waale dekhey, sangeenein aur bhaale dekhey/ sadakein theen har camp sey jaari, paani tha har pump sey jaari,' and so on. [Saw His Highness the Duke of Connaught; saw the great Minar of Qutub Sahib; saw men who were white, and men who were dark; saw platoons and regiments, saw band after band playing music; saw bayonets and spears everywhere; saw the sight of neat roads issuing forth from the (Duke’s) camp; and the sight of water gushing forth from every single pump…]. A sense of wonder and celebration ran through the verses, one can see.

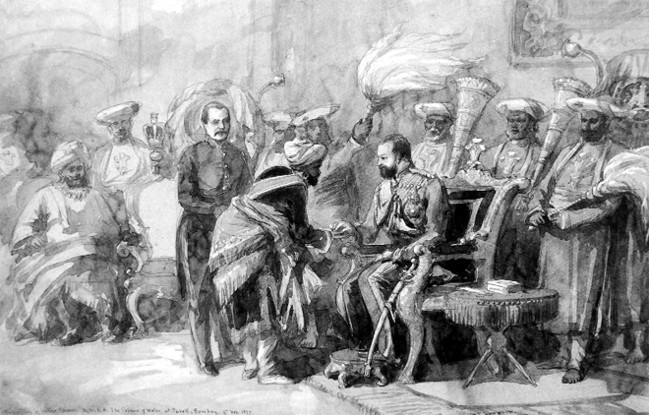

Not that kind of wonder really, but a sense of celebration certainly ran through the exhibition in the Queen’s Gallery, as also through the catalogue thoughtfully put together by Kajal Meghani. The Prince’s was going to be an educational tour, considering how recently the major parts of India had become part of the British Empire and how useful it would be for the future King-Emperor to know the land. The Press in England had also pushed the idea, The Times saying that it was the ‘greatest necessity’ in the government ‘of a vast and various Empire’ to cultivate 'mutual intelligence, mutual respect, a sense of unity, and increasing sympathy' with its outlying parts. But preparations were needed: initial anxieties having been allayed, the Prince began to learn about India through acquainting himself with Indian artefacts which Sir George Birdwood, curator of the South Kensington Museum, introduced to him; discussions were held about the exchange of gifts with Indian princes, a large number of whom were ‘independent’, but had sworn loyalty to the Crown; instructions were issued to British officers in India saying that no ‘ceremonial Durbars’ will be held, and there will be no exchange of presents; all the same, gifts were readied for giving to Indian chiefs and nobles: ‘gold and silver rings, badges, bracelets, watches and lockets’, as also medals and meaningful books. Artists, advisers and journalists who were to accompany the Prince on this grand tour were selected. Finally, the journey began: on October 11, 1875. A month later, his ship arrived in Bombay where, against all expectations, the royal visitor was greeted by crowds ‘glittering with gems’ and ‘swaying to and fro’ in an attempt to catch a glimpse of him.

From that time onwards, it was one roller-coaster tour for the Prince of Wales, for he was everywhere: Ceylon briefly first, but then back to India: Madurai, Trichinopoly, Calcutta, Benares, Lucknow, Lahore, Amritsar, Agra, Gwalior, Jaipur, Nepal, Indore. By the time he left India, he had ‘travelled the length and breadth of the Indian subcontinent and had met more than 90 Indian rulers’. Everywhere, special programmes, special visits, were organised in his honour. Descriptions of his visit were being recorded all along: thus, at Trichonopoly there were fireworks, 'pouring like lava, like floods, now blue, now orange, now green, from some over-swelling fountain'; at Benares, the river Ganga was 'covered with lamps… little earthen vessels, bearing their cargoes of oil and wick' which 'sparkled and glittered …It seemed as though a starry sky were passing between banks of gold'; in front of the Taj at Agra, the Prince 'stood and gazed, almost trembling with admiration'; in Nepal he was able to see 'the range of the Himalayas lighted up by the setting sun' and watch the 'rose hue steal up from the darkening base over the pure white summits'. These visual experiences apart, everywhere the Prince was loaded with gifts presented to him by his ‘loyal subjects’, many of them rulers and princes of great states: the choicest arms and armour, pieces of encrusted jewellery studded with ‘vast diamonds, emeralds, rubies and pearls’; delicately wrought artefacts and elaborate caskets containing formal addresses, which were read out to him everywhere, now by the Parsis of Bombay, now by a group of talukdars, now by ‘the people of Punjab’.

Everything that came back with the Prince to England went immediately on display in the Indian Museum at South Kensington in London, and then travelled to countless places in Europe, the displays looking like ‘a scene from the Arabian Nights'. It is these objects that were now on view in the Queen’s Gallery in London: a glittering sight, tinged, at least for me personally, with a touch of heaviness, for these after all were gifts rendered unto a master by the subject people of our land, even if it was close to a century and a half ago.

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.