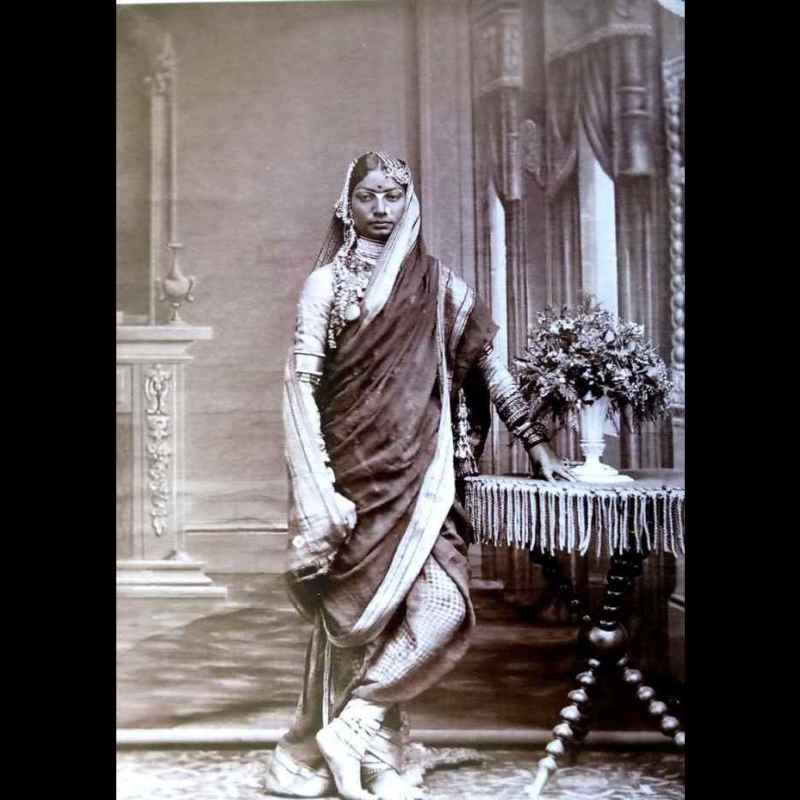

With 6,050 individual photographs, contained in 105 albums and some loose prints, and 1,941 glass plate negatives containing 2,008 images, Sawai Ram Singh II of Jaipur deservedly carries the reputation of having been a ‘Photographer Prince’. Prof. B.N. Goswamy writes about the royal’s passion for photography and his ‘photukhana’. (In pic: Royal eye—Unidentified woman of the zenana at Jaipur, possibly Ram Sukee, photograph by Sawai Ram Singh II, c. 1870; Photo courtesy: The Tribune)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh, published under the title ‘A Photographer Prince’ and is reproduced here with permission.

Saturday, 1 January, 1870. At 11 o’clock photographed the Duke of Edinburgh (and) then returned home.” “Wednesday, 16 February. Went into the photography room. Printed photographs.” “Tuesday, 29 March: Jaipur; took photographs from the corner of the palace.” “Tuesday, 12 April: Jaipur; Did some photography related work. The (photography) chemical compound mixture (which had got) spoiled had to be fixed.” “Friday, 3 June: Jaipur; Took some pictures in the aatish (stables) some of which did not turn out; then in the photography department, took 3 photos of the zenana out of which one was spoilt.”

If one did not know any better, the above scattered notes one would have thought came from a professional photographer’s carefully kept diary. They are, in fact, excerpts from a kind of roznamcha—journal that a Maharaja kept: Sawai Ram Singh II of Jaipur (ruled 1835 to 1880). If one were to relate this to the figures that Mrinalini Venkateswaran, who has been documenting the royal collection of photographs at Jaipur, gives—6,050 individual photographs, contained in 105 albums and some loose prints, and 1,941 glass plate negatives containing 2,008 images—one knows that photography was a royal passion at the Jaipur court. And, deservedly, Sawai Ram Singh, apart from being a reformist and forward-looking ruler, carries the reputation of having been a ‘Photographer Prince’. He ruled with as much flair over his princely state as over the small ‘retreat’ that came to be called his ‘photukhana’ at Jaipur.

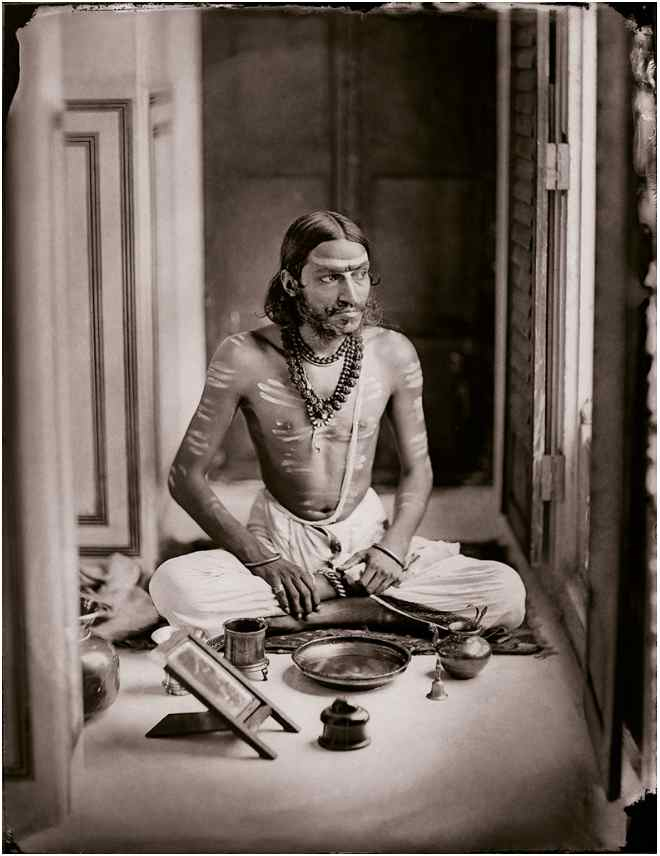

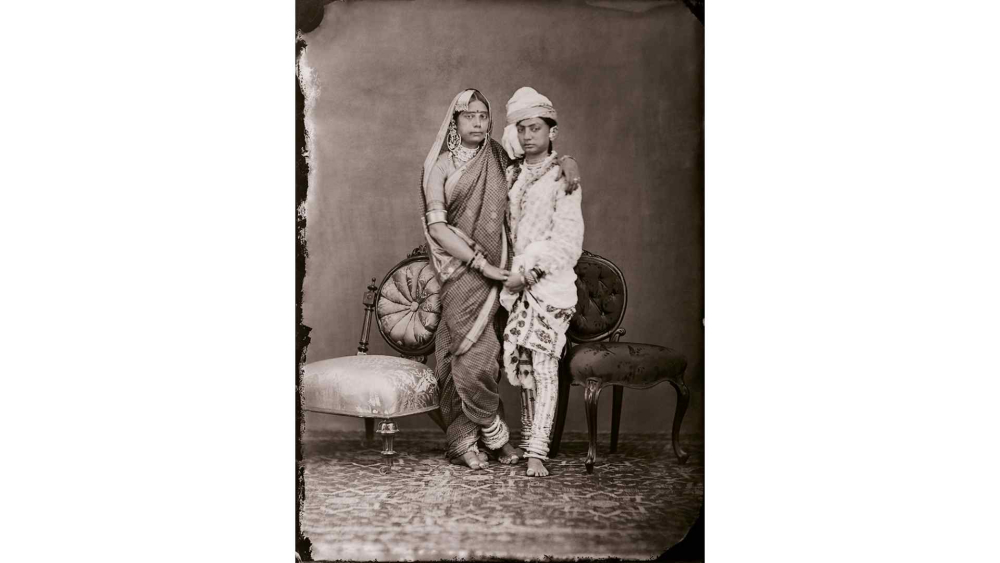

No one knows exactly when the Maharaja first got to know the exciting new device called the camera: there is a suggestion that it was in 1864 when the photographer T. Murray came to Jaipur; at the same time there are surmises that it was as early as the 1850s. But whatever the date, the Maharaja embraced photography from the heart. He acquainted himself with the best available equipment and acquired it, learnt how to photograph, took his camera/s with him on his journeys—whether to Calcutta or Benares or Agra—and began to create what one could term an archive of whatever was around him in Jaipur itself: portraits of people, whether local nobility or distinguished visitors; views of the city taken from carefully chosen angles; landscapes; photographs of himself; also, intriguingly, a record of the women of the royal household.

Also read | The Artefacts of a Dalapathi: A Photo Narrative

When western visitors came to Jaipur, the Maharaja was keen to learn from them all that they knew about photography; whenever he travelled himself, he wanted to record people and places: the Maan Mandir at Benares, the Taj, of course, at Agra, the Garh Palace of Bundi, the ruins of the Residency at Lucknow, and so on. Well-established photographers or photographic firms—among them T. Murray, Bourne & Shepherd, Sache, Lala Deen Dayal—came to visit Jaipur and take photographs. When the French writer and traveller, Louis Rousselet—that ‘prince of the darkroom’—came visiting in 1866, he sat down with the Maharaja and, as he notes, “The conversation then turned on photography (he is not only an admirer of this art, but is himself a skilful photographer), and afterwards on France, of which we talked a long time.” One does not know whether Rousselet got to see the impressive array of cameras and processing equipment that the Maharaja had acquired, but clearly, as can be seen in the royal collection at Jaipur, the most technologically advanced pieces were there: a chemical sensitising box that came from G. Knight & Sons, a big portrait lens by Voigtlander & Sohn, a wet-plate sliding box camera made by J. Spencer, a stereo box camera from J.H. Dallmeyer. The Maharaja evidently took pride in his collection, whether of equipment or photographs, and when he mounted his photographs on cards, he would put his personal seal on the card using a specially made embossing tool.

There are myriad aspects to photography and the Maharaja’s passion for it that Mrinalini, to whose efforts at researching the Jaipur archives one owes a lot, draws attention to in her studies. But among the more absorbing of these is the manner in which the Maharaja documented the women of the royal household—the zenana as it was called—mostly pardayats or concubines, some others who were house-maids and performers. It is a whole series of photographs, some of them of outstanding quality, unlike any that one sees from other courts of those times. The Maharaja seems to have been obsessively drawn to them. Of great interest in this context is a passage that the English artist Val Prinsep, who kept visiting Jaipur, wrote.

Also read | Jyoti Bhatt: A Quest Beyond the Woven Culture and Symbols of Indian Heritage

“We (the Rajah and I) became great friends . . . Among the curiosities of Rajput Courts are the nautch girls, who are a kind of privileged people, and wander through the palaces unveiled and unmolested. I had noticed a number of them here, and, presuming on my intimacy, got the Rajah to order one of the girls, whose photograph (taken by the Rajah?) I saw, to sit. On Tuesday, then, I had a sitting from her. She is not young, but has a remarkably fine head . . . She wears a long flowing robe and winds her drapery around her with the air of a queen . . . Ram Sukee, this nautch girl, is a great friend of the Rajah, and soon he came to see how I was getting on, and pottered around me, arranging drapery and fancying he was of great assistance . . .”

Here we have it, once again: an intimate look at the private world of Sawai Ram Singh II, at the centre of which seems to have stood the ‘photukhana’ of that ‘Photographer Prince’.

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.