The art of photography has come a long, long way from those early days when photography was first introduced to the world. Prof. B.N. Goswamy recaptures the debate that developed in the art world, and the fissure that appeared. (Photo courtesy: Libreshot)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh and is reproduced here with permission.

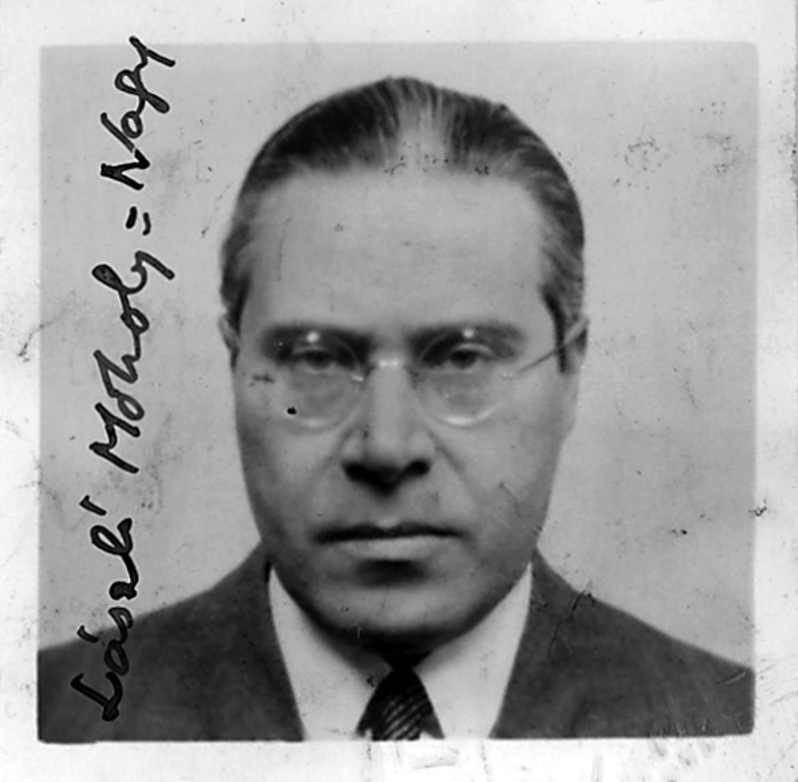

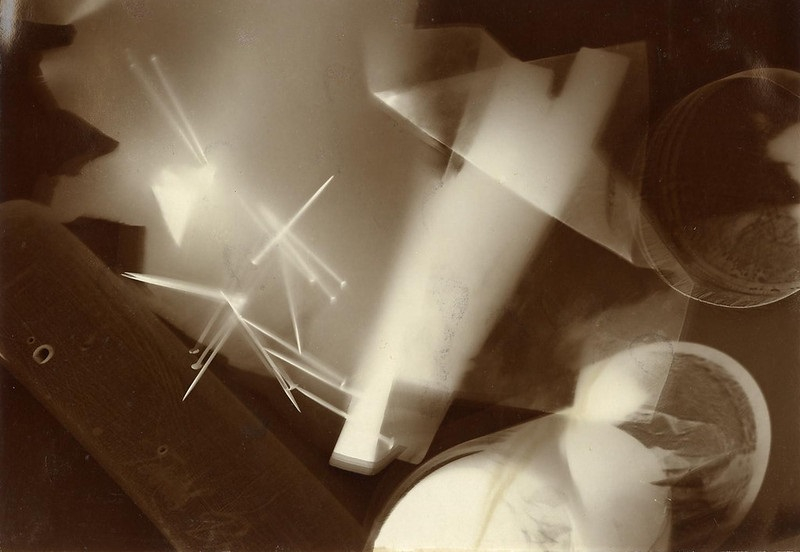

Over the years, one has stopped being surprised by the level of prices which works of art, especially in the fiercely competitive, and curiously whimsical, market in the West fetch. But even I was not prepared for the price someone mentioned to me recently of a photograph—not a painting, not some classical sculpture, but a photograph—according to an estimate given in a catalogue of a New York-based auction house. The work was by the celebrated twentieth century Hungarian painter, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, who was also a visionary photographer. And the price? Between 90,000 and 120,000 American dollars, which translates into something between Rs 35 lakh and Rs 45 lakh. This passes my comprehension. Completely.

Obviously—and one says this with some relief—this is not what every photograph fetches. But the art has come a long, long way from those early days when photography was first introduced to the world. In fact, it had to struggle long and hard even to gain recognition as an art form.

The society in which it appeared—France of the 1930s of the twentieth century—was especially conservative, with its Academy and Salon structures wielding such power in the world of art. Everyone was excited, for the significance of the new development was apparent, but everyone was also a little nervous, a little unsure as to where this new-fangled invention was going to lead the world.

Divisions appeared rather quickly. There were those among the artists who saw it as a tool, invaluable because of the incredibly accurate ‘sketches’ from nature it could supply them with; but there were also others—those with the literal reproduction of the visible world as their chief aim—who perceived it as a threat, for it could render them completely obsolete, even redundant.

Also read | The Artefacts of a Dalapathi: A Photo Narrative

The debate that developed, and the fissure that appeared in the art world, are fascinating to follow. The highly respected Romantic painter, Delacroix, signed himself up as a charter member of the first Photographic Society to be founded in France in 1851, commending the use of the new invention to the favour of fellow artists. Daguerreotypes—this, as one knows, is how early photographs were designated, after the name of the inventor, Louis Daguerre—were interpretations of nature, he wrote: they revealed her secrets. There was a note of caution in his words, but also great enthusiasm: “If a man of genius uses the Daguerrotype as it should be used, he will elevate (his art) to a height hitherto unknown.”

But others were less convinced, and very uneasy. When photographers—who had begun to organise themselves rapidly and were refusing to be treated simply as merely ‘factotums to art’—succeeded in getting a small section of the French Salon of 1859 devoted to photography, the step aroused much ire.

Seeing it as ‘an impertinence’ the greatly influential Baudelaire, a literary icon of his times, railed against these developments. Photography, he said, was “the mortal enemy of art”. His attack was directed as much against the French Academy, as against the public, which looks “only for truth” in Art.

There was anger in his words, and irony. “Since photography gives us every guarantee of exactitude that we could wish, then photography and Art are the same thing . . . If photography is allowed to stand in for Art in some of its functions it will soon supplant or corrupt it completely.” Like a pontiff, he held forth: “Photography must return to its real task, which is to be the servant of the sciences, and of the Arts, but a very humble servant.”

Some people took the matter to court. When, after long arguments, the French court announced its decision in which photography was declared to be an Art, the issue was by no means settled. At least in the minds of many artists.

There were angry protests, and the judgement met with a hostile response, a large number of artists, including that brilliant Classicist, Ingres, sending up a petition. Never, they stated, could photography “be compared with those works which are the fruits of intelligence and a study of Art.”

Also see | Pashmina Wool, Freezing Winters and Nomadic Life: The Changpas of Rupshu

To many, doomsday appeared to be close. “I greatly fear”, wrote Flandrin in 1863, “that photography has dealt a death blow to Art.” In all these utterances, one does not fail to notice of course that Art is always spelt with a capital “A”, while photography has to remain content with a small, lower-case “P”.

But there was no stopping photography. The story of French painting in the nineteenth century is well known, and the manner in which photography influenced the work of so many of the greatest artists of that century—Courbet, Monet, Degas, among them—is well documented. The “humble servant” of Baudelaire’s description was to rise many notches upwards as the century progressed and melted into the next one, in which it emerged triumphant: a noble and lively art in its own right.

According to calculations based on the sale of materials, the journal “Photography News” estimated in the year 1863—this is less than a quarter of a century after the camera was invented—that 105 million photographs were produced in the previous year in Great Britain alone. This I find to be a stunning statistic.

Other Cameras

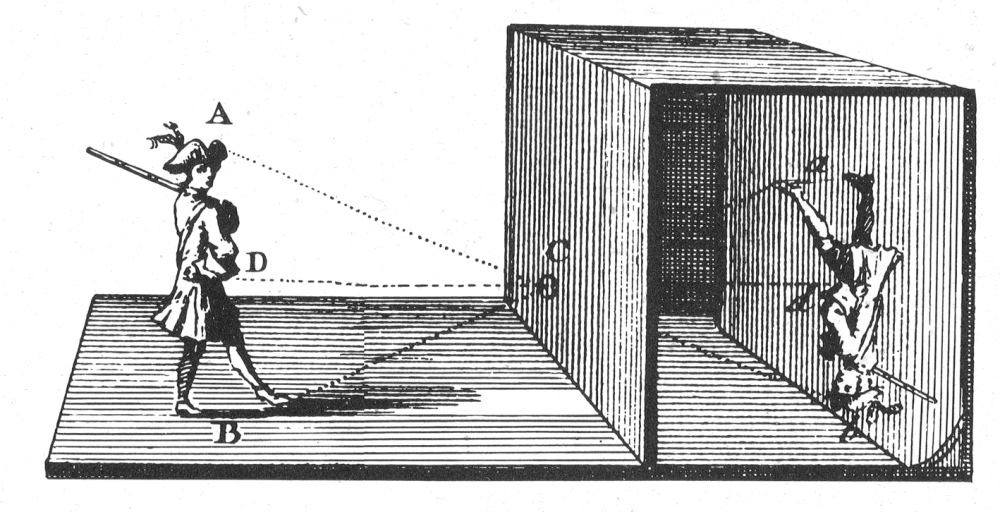

The fact may be little known to many, but artists in Europe knew another device, well before the invention of the “photographic camera”, which they put to their own use. Called the camera obscura—literally, the “dark chamber”—this was an apparatus “which projects the image of an object or scene on to a sheet of paper or ground glass so that the outlines can be traced”. The device has a long history, and many names of scientists and artists—those of Roger Bacon, Leonardo da Vinci, Vasari, Johann Kepler, among them—come up whenever an understanding of the device is spoken of. Topographical paintings and drawings were widely made with its assistance in the eighteenth century, and one reads about an apparatus, “somewhat like a sedan chair”, in which the artist could sit and draw, actuating at the same time bellows with his feet to improve the ventilation!

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.