The Partition of India in 1947 was the largest human migration in recorded history. Around 15 million people were uprooted as a consequence, and the Punjab region—a part of which was incorporated into Pakistan—was one of the worst-affected areas in the subcontinent along with Bengal. Prof. B.N. Goswamy brings forth some voices of people from both sides of the border that shed light on the memories of home and the sense of loss following the Partition. (Photo Courtesy: The Tribune)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh, and is reproduced here with permission.

All that I am going to do in this piece is to reproduce some voices, almost exactly as they were recorded. I have accessed them via my artist-friend, Manisha Gera Baswani, who lives in Delhi, and has long been interested in photographing and interviewing artists at work. She was recently in Lahore, attending the Lahore Biennale, and there she set up an engaging installation in the Shahi Masjid, with ‘packages’ of these voices and photographs stuck in locally purchased jute bags filled with wheat.

This is obviously an imperfect and partial selection, for there were many, many more. But even this will convey, I hope, something of the flavour of nostalgia, of memories, of affection, and, above all, of the sense of loss on both sides of the border.

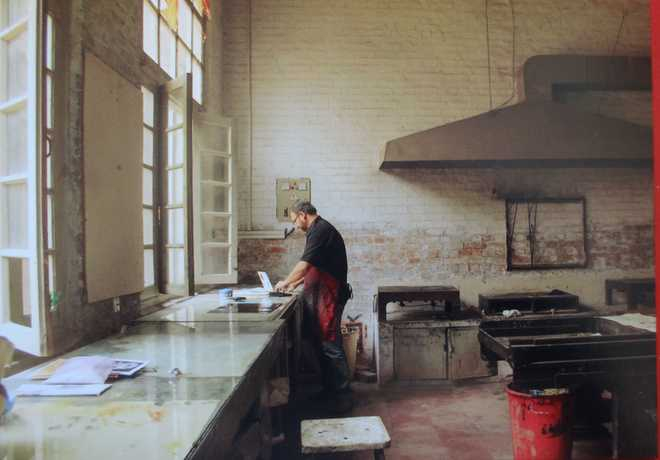

The voices of these artists convey the flavour of nostalgia, of memories, of affection, and, above all, of the sense of loss on both sides of the border (In pic: Imran Qureshi; Courtesy: The Tribune)

“Dad says it’s all very vivid,” said Rashmi Kaleka from Delhi. “When the slaughter started, the sky was empty of all birds, the skies carried no bird sound. (A memory…) In the midst of the cruel violence of 1947, Shankar Ohri, my mama (mother’s brother) is agonising over his ‘door’. He is missing it. He can resist no longer and pays fifty rupees to two Gurkhas to accompany him. Armed with a screwdriver, he makes his way from Jalandhar to Lahore. Warily, he enters his Lahore home and unscrews the door. No one remembers how he got back. He built a house in Shahdara, Delhi, and fitted his door in it.

Reminds me of ‘Door’, Makhmalbaf’s film. A man left with only a door of his house roams on barren land on the island carrying it on his back.”

Muhammad Atif Khan, from Lahore, recalled: “Both of my parents, father, Muhammad Idris Khan, and mother, Rabya Kihwar, were born in a small town named Gudiyani (90 km towards west from New Delhi). They spent their childhood and teenage there until they got married and moved to New Delhi for my father’s job. They lived over there for a few years until the Partition of British India. Then they migrated to the newly formed state, Pakistan, where they spent the rest of their lives.

My mother always talked about a Sufi saint Mian Munna Sahib whose shrine was equally respected among local Muslims and Hindus of Gudiyani. Since her childhood, my mother used to visit and pray there. She believed that lost things will be found if one prays a ‘mannat’ to Allah on behalf of his beloved saint, Mian Munna Sahib.”

Rashmi Kaleka remembers her uncle brought the door of his house from Pakistan to India after the Partition and fitted it into his new house in Delhi (In pic: Rashmi Kaleka; Courtesy: The Tribune)

Nilima Sheikh lives in Baroda. “Most people of my generation,” she recalled once, “from northern post-independence India would have stories to recall of their loss of familial home: stories about the wrench of displacement that have got distilled into family lore. My story is indeed quite different, about coming to find home in Lahore, and dates to the late 1920s. My maternal grandparents lived in Burnley in the north of England where my grandfather, Naunidh Rai Dharamvir, was a practising doctor. Their home was often a resting point for visiting nationalist Congress leaders and they were increasingly drawn into the fervour of nationalist aspirations. They were persuaded by Lala Lajpat Rai, who had just lost his mother to tuberculosis, which was rampant in South Asia, to come and set up a hospital in Lahore. So they came and started afresh in Lahore (founding a hospital). It is heartening to know that the Gulab Devi Memorial Hospital for women, named after Lala Lajpat Rai’s mother, continues to be a landmark institution in Lahore, and still bears the same name.”

Gargi Raina from Delhi related this experience: “In 2001, I was invited by Salima Hashmi for a Women’s Peace Workshop in Lahore and was able to trace my father, Satyendra Kumar’s, footsteps after 54 years to his childhood home, Fairfields (now Fatima Jinnah hostel]. When I got to Ajudhyapur, the village from where a group of Muslim men in 1947 had come to save Fairfields (with my 17-year-old father and family inside) from being burnt to the ground by a huge mob, the entire village turned out to meet me as it did for my father a year before. Shaukat Kang, a village elder placed his hand on my head and gave me a joda, an unstitched garment given to a daughter on her first trip back home after marriage.”

Imran Qureshi from Lahore has a recollection. “(Some years ago, I was in Jaipur.) While my friends were captivated by the magic of Bollywood on the silver screen, I suddenly found myself torn between the spectacle of the film and my father’s telephone call from Hyderabad, Sindh, to me in Lahore, before I was to travel to India on a study trip of the National College of Arts. In 1992, I was a 3rd-year student at that time. My father Inam Ullah Qureshi’s wish was for me to visit his family house in Jaipur, which they had left behind, during the time of Partition. My father’s voice pulled at my heart and I decided to leave my friends… as they watched a Bollywood film, searching for the ‘home’ that he had nostalgically mapped out to me on the telephone as if it were yesterday.

Numerous people left their homes on the other side of the border but can still map out the way to their houses as if they had left yesterday (In pic: Muhammad Atif Khan; Courtesy: The Tribune)

As I walked the narrow lanes of the Pink City of Jaipur, every landmark lovingly described by my father appeared almost magically before me — the signs, the turns. My heart started beating faster as I saw myself nearing my destination. I remember being overwhelmed with emotion. And then, I stood quietly in the street where once stood ‘Abba’s home’.

An old man sat outside a house, perhaps with his grandchildren. I felt the urge to start a conversation with him, ask him about my father’s home, and many more questions that were coming to my heart and yet I just could not bring myself to…

I walked away — without identifying the house.”

I find some of this very moving.

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.