Sindhu or River Indus emerges from the Himalayas, and flows through the Punjab into Sindh, dividing it lengthwise, as it flows towards the delta into the Arabian Sea. Going back in history to 2500 BCE, the period of the Indus Valley Civilization, indigo, Indigoferra Tinctoria grew abundantly on the banks of Indus. When the British annexed the Province of Sindh in 1843, indigo was one of the chief exports of the Province. The cultivation and production of indigo dwindled by the late 19th and early 20th century.

One of the greatest accomplishments of the subcontinent was the development of the technology of dyeing and patterning of fabric.The celebrated stone statue of the ‘Priest-King’, discovered at Mohenjodaro, has trefoil motifs and circles on the draped shawl. It is believed that the ‘Priest-King’ is wearing an ajrak—the traditional textile of Sindh that is resist–printed, mordanted and dyed, in madder and indigo, a printed cloth whose legacy continues till today.

(top) ‘Priest King’ (front view) discovered at Mohenjodaro He is wearing what is believed to be an ajrak; (below) ‘Priest King’ (reverse)

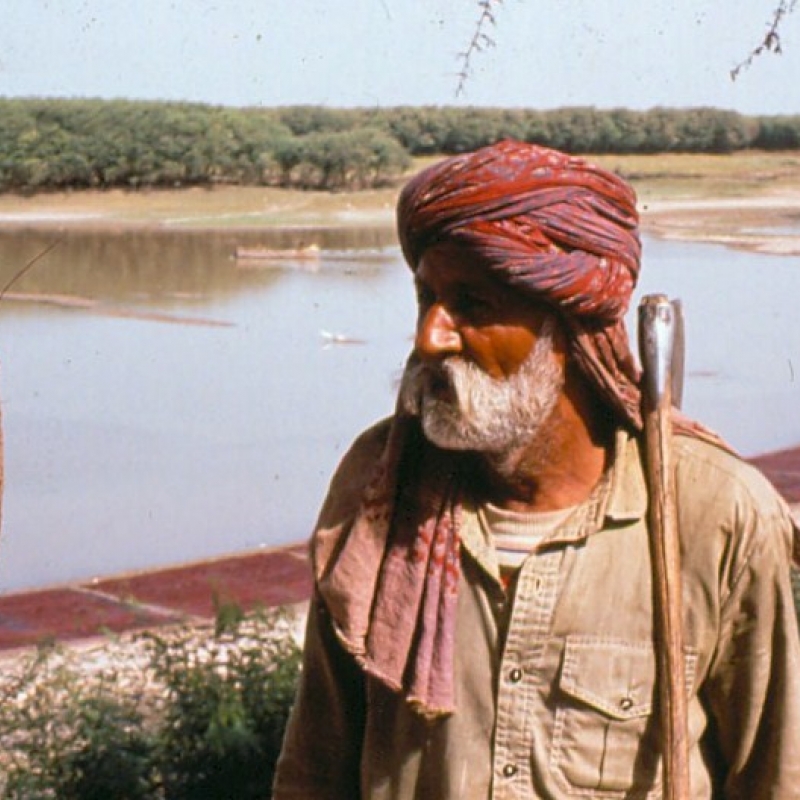

From the 9th to the 14th century, Arab merchants traded spices and textiles between Sindh and Egypt. The name ajrak, in all probability, is derived from azrak, which means blue in the Arabic language. The people in Sindh hold this textile in great reverence—they regard it as almost sacred. It is common to see men, women and children all wearing it. There is no association with class or status; ajrak has the same significance for the rich and poor. No colour or pattern distinguishes its value; the only difference would be the use of an expensive or cheaper base cloth. This cloth is not only used on special occasions, but also has multifarious usage in everyday living. From birth to marriage, until death, ajrak commemorates all significant events of the life cycle. It is used and reused till threadbare.

(top) It is common to see men, women as well as children wearing ajrak in Sindh. (below) The back of a quilt (ralli), made with recycled ajrak. This design is very common for traditional ajraks. The end panels (pallus) feature a pattern called paland and the pattern on top is called chakki (wheels). One can also see the tepchi—running stitch in madder-coloured cotton thread. The other side has cutwork appliqué.

A young boy draped in ajrak

Ajrak as a canopy for this bullock cart

The artisan works in total harmony with his environment, using indigenous materials except for the dyes. The process is highly complex, comprising 21 stages. It takes the craftsmen almost a month to complete a traditional teli (oily) ajrak.The cloth is washed thoroughly in the river or lake at every stage of the process. Early in the morning the washers are seen at the banks of the river, or lakes with twisted bales of cloth at different stages of production. The cut fabric, base cloth (kora latha) is coiled and steamed on a copper vat, khumbh through the night. The cloth is brought back to the workshop and soaked in Eruca Sativa seed oil to give it an oil treatment that distinguishes it as the superior teli ajrak. The ajraks are then tied in a bundle for 15 days so that the oil saturates each fibre.

The cloth is then ready to receive the first printing of the white outline of the pattern (kiryana)—the resist paste of lime and Acacia gum—dollowed by printing of the black areas by ferrous (kut). The cloth is further printed by a resist and mordant paste (kharrh) comprising of gum, flour, Fuller’s earth, alum, molasses and a number of herbs and spices. This helps protect the printed areas against the indigo dye and simultaneously the other areas turn red when dipped in the alizarin dye. The master dyer dips the cloth in the vat (kun) for the first indigo (nir) dye.

(top) Steaming of the cloth (khumbh) and (below) Preparing the mud resist (kharrh)

Resist printing (kharrh). This helps protect the printed areas against the indigo dye and simultaneously, the other areas turn red when dipped in the alizarin dye

The dyed fabric is taken to a river and submerged in water early in the morning (vicharrh), before it is dipped in alizarin in a copper vat till the red becomes deep. Camel dung is used to remove excess tanning from the ground and make the white clear and brilliant. Ajraks are spread on the riverbank where the artisans sprinkle water intermittently as the cloth dries. Alternate drenching and drying (tapai) helps to bleach the fabric. This facilitates the maturing of the colours and the sun bleaches out the white areas.

Printed again with the mud-resist mixture (kharrh) it is sprinkled with dry, sifted cow dung, the ajraks then go through another indigo dip before taken to the river for a final wash. The result is the precious, jewel-like ajrak. This is printed on both sides (bi puri). There has been a steady decline in number of ajrak karkhanas, from the thousands in the last century to a few dozen at present, but the labour intensive process has persisted for well over a millennium. There are cheap imitations of ajrak through screen-printing, but the discerning eye of the user in the rural areas has ensured the continuity of good quality hand-blocked ajrak.

(top and below) 'Trey hashe wali' (with three borders) ajrak

I was a consultant for a Pilot Project initiated by AHAN, Ek Hunar Ek Nagar, by Government of Pakistan in four ajrak centers in Sindh last year, with the mandate to develop a model that can be replicated in other ajrak centers. The objective was to revert to the traditional use of indigo and madder and introduce variations that could help enlarge its market beyond the traditional usage.

I began my intervention by asking the master craftsmen, what is it that is the identity of an ajrak, is it distinguished by its colours, the patterns, or the process? What is essential to preserve in its making, otherwise intervention by the designers can bring more harm in losing the essence, the purity or the sacredness of the textile to the domestic wearer and would make the textile irrelevant to the community.

(top) Ismail Khatri with his brothers in Ajrakpur, Gujarat and (below) Indigo and madder-dyed ajrak at KOEL, Karachi

I had met Ismail Bhai’s family in conferences and in Delhi, and saw their, beautifully printed, inspiring ajraks. When I visited Ajrakhpur and other centers in Bhuj, I was disappointed to see that despite producing the stunning ajraks that are popular in the western markets and the cities, the use of ajrak in their own environment had gone. A few wore ajrak turbans as a ceremonial mark to identify themselves as craftsmen but ajraks were missing in their homes or in the local market. We subsequently invited Mohammed Aziz to teach our khattris ajrak on silk, there was a fair exchange of skills and he went back enriched with the traditional method of printing continuing on this side of the border.