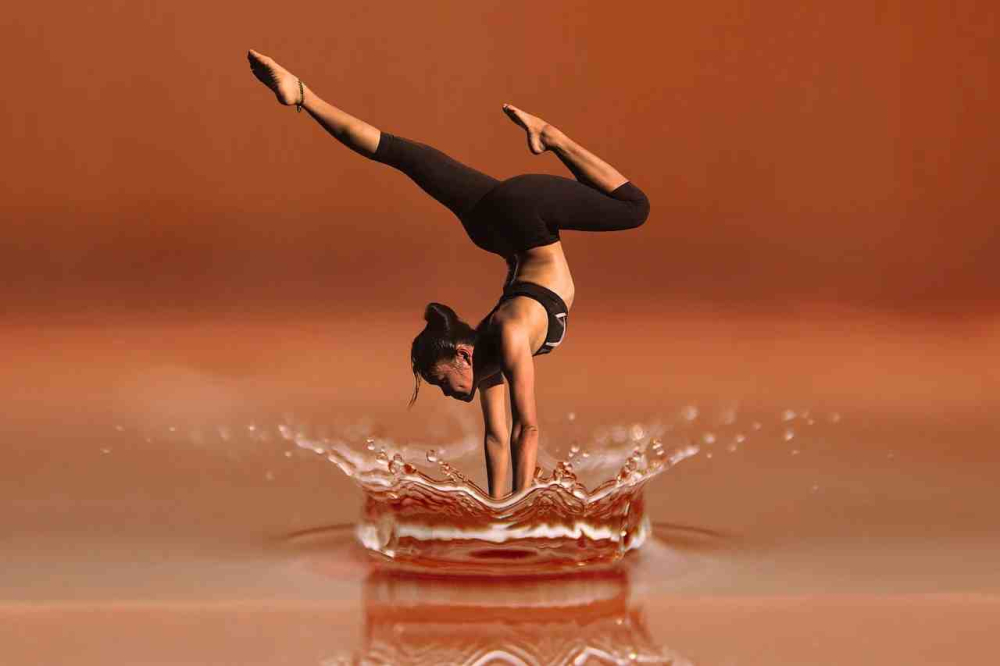

Activities around the International Day of Yoga (June 21) have been repurposing yoga and naturopathy into our lives as the ‘new normal’ in a post-Covid19 world. While heavily laced with Indian ethical and spiritual doctrines, naturopathy as a system is, in fact, a German import. We attempt to trace the overwhelming connection between Naturopathy and a yogic way of life and how it gained ground in India. (Photo courtesy: Pixabay)

As the world adapts itself to the concept of a ‘new normal’, one of the learnings of the Covid-19 pandemic has been the importance of a good immune system and overall health. Globally, the attempt is to explore practices that would boost body’s immunity and encourage an overall healthier lifestyle. This has resulted in an amplified interest in alternative therapies such as yoga and naturopathy. In India, news websites and television programmes have been dedicating prime space and time to such topics. Even the central government has taken proactive measures in COVID-19 pandemic mitigation, prevention and management through Indian systems of medicine.

Interestingly, though, while these Indian systems are rooted in natural cures, ‘naturopathy’ as a discipline in alternative medicine is an import from Germany via the US in the late nineteenth century. However, it was understandably not considered alien by Indians as they could relate with the concepts of the ‘Five Great Elements’ to the Pancha-mahabhutas (mud/earth, water, sunlight, air and ether) of Ayurveda and the principles of ‘fasting and vegetarianism’, which were the founding pillars of European naturopathy. It was readily adopted as practices of fasting (‘lankhanam paramaushadham’, that is, fasting as a panacea for all diseases), exercise, fresh air and other similar principles were already a part of Indian culture.

Also read | The Pātañjalayogaśāstra alias the Yogasūtra and the Yogabhāṣya

The Origins

Naturopathy evolved in post-industrialisation Europe of the 1850s, as a result of the unhygienic, overcrowded conditions people started living in. Poor nutrition and high stress led to rapid spread of communicable diseases through virus, bacteria and germs, and subsequent deaths. Fed up with the inefficacy of modern medicine at the time, a small section of medics focused on protective mechanisms that would help people develop a resistance against these germs and microbes. However, their voices were largely sidelined. Undeterred and inspired by Hippocrates (400 BCE), who stated that ‘Nature is the physician of disease’,[1] this section began to be recognised as ‘naturopaths’, and the European Natural Cure Movement was born.

By the 1890s, this movement had spread to the US. The term ‘naturopathy’ was coined by Dr John Scheel in 1895 there, and was later bought by Dr Benedict Lust. Lust, along with his German colleagues and mentors—Dr Henry Lindlahr, Louis Kuhne and Father Sebastian Kneipp—took on the charge of popularising the practice. It caught the attention of the rich, noble and elites of the time; as it did of Dronamraju Venkata Chalapathi Sharma from Visakhapatnam.[2] Sharma was introduced to naturopathy and Kuhne’s methods through a German contact in the Indian Railways. He was so taken by the concept that he went to Germany, learnt German, became a disciple of Kuhne and Kneipp, and eventually translated Kuhne’s book New Science of Healing into Telugu in 1894.

Across Indian Shores

Upon his return, Sharma tried his best to propagate the system in India—even carrying hip and spinal tubs to patients’ homes to spread the message of Nature Cure and hydrotherapy from door to door. His efforts were fruitful, and soon he gained many followers. From the Andhra province, lawyer-turned-naturopath K. Lakshmana Sharma took up the cause in Tamil Nadu. A Vedic scholar and acharya, he published numerous books in the early 1900s, including the treatise Practical Nature Cure.

Also read | Yoga: A Historical Overview

Interestingly, around the same time, one found an underlying spirit of Oriental sciences and Eastern—such as Prana and Brahman—heavily embedded in Lindlahr’s books like Nature Cure (1914).[3] The ancient Vedic teachings, mentioned in the Varaha Upanishad of Krishna Yajurveda, about sankalpa (thought ideation) were also mentioned, while explaining the relation of thought and feeling to health and disease.[4] The concepts of ‘eternal thought in the eternal mind’ (Bhagavad Gita), the unity of Creator and the Created (Vedic philosophic teachings) and the Kaivalya Upanishad’s dictum of ‘Thou art that’ found mention in Lindlahr’s naturopathy philosophy.

Back in India, Shrotriya Krishna Swaroop’s translation of Kuhne’s New Science of Healing into Hindi and Urdu in 1904 took naturopathy to the north. Many—including those involved in the Indian freedom movement such as Mahatma Gandhi and Morarji Desai—were staunch believers in naturopathy, which added to its mass appeal. From 1901 onwards, Gandhi widely started using Kuhne’s hydrotherapy and Adolf Just’s mud therapy, and even wrote several books on it. A popular example of this is how he treated leper patient Parchure Shastri, a Sanskrit scholar and his co-prisoner from jail, using mud therapy.

The Inclusion of Yoga

Since most of the early naturopaths were either practising vaidyas (traditional physicians) or those in vyayamshalas (traditional gymnasiums), they were very quick to imbibe the yogic ‘physical’ aspects of ‘physicultopathy’ prescribed by European naturopaths. Soon, Indian naturopathy started taking shape. The inherent Indian principles in naturopathy fitted well with Gandhi’s Swadeshi movement, which was gathering momentum at the time.

Yoga’s perception as a pure spiritual pursuit started changing into a practice for health and well-being with the advent of Nature Cure ashrams in the 1920s. Soon, yoga became an integral part of the naturopathic way of life, and in naturopathy centres and colleges that were mushrooming across India. Yoga was incorporated as a subject in the naturopathy curriculum in 1920; the medical degree is now offered as Bachelor of Naturopathy and Yogic Sciences (BNYS) in India. This inclusion of yoga is unique to India, unlike other naturopathy curricula worldwide. Both yoga and naturopathy have a common foundation—relying on internal strength and augmenting resources from within. External support in terms of material goods (like drugs) is a strict no in both the systems. Both lay stress on self-practice and observation. It was a perfect match!

Naturopathy, which may have had originated in Europe, is heavily laced with Indian ethical and spiritual doctrines. Hence, starting from the training to its implementation, it has the aroma of Indian soil. In the light of the ‘new normal’ all over the world, it is not unsurprising that there is a concentrated shift towards incorporating naturopathy and yoga into our lifestyles more vigorously, thus bringing in sustainable healthcare practices.

This article was also published on The Indian Express.

Notes

[1] Louis Kuhne, Wikipedia. Accessed June 17, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Kuhne.

[2] N.V.R. Swamy, ‘The Miracle of Nature Cure’, Social Welfare, edited by Freda Marie Houlston Bedi, Vol XIV, No. 1 (April 1967). Accessed June 18, 2020, https://bit.ly/37CuuRb.

[3] These books later formed a part of the textbooks for the Bachelor’s degree course in naturopathy.

[4] Henry Lindlahr, Nature Cure: Philosophy and Practice Based on the Unity of Disease and Cure (Illinois: Nature Cure Publishing, 1914), pp. 31 and 94.