According to the Hindu calendar, Makar Sankranti marks the sun’s transition from the tropic of cancer to the tropic of capricorn (makara). It signifies the onset of the harvest season, an auspicious time of the year throughout India.[1] In Gujarat, it is celebrated as Uttarayan, also known as the ‘festival of kites’. ‘Uttara’ means north and uttarayan is defined as the day when the sun begins its northward journey marking the end of winter.[2] The celebrations, spread across two days—14th and 15th of January—primarily revolve around kite flying. While January 14 is called Uttarayan, the next day is regarded Vasi (literally, stale).

People start preparing as early as March of the previous year, and the festive fervour is at its peak during the months of November and December. Uttarayan involves three essential elements—patang (kite), firki (spool) and manjha (string coated with rice paste mixed with fine glass powder).

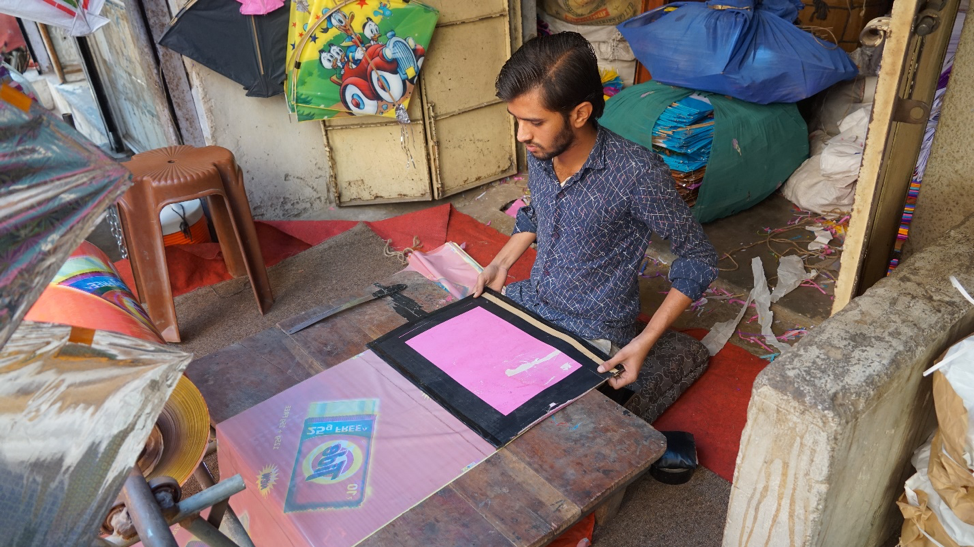

Kite making is a complex process. According to Abdul Wahid Khan Pathan, a local kite maker in Jamalpur area in Ahmedabad, making of a kite involves four to five stages—dyeing kite paper (locally known as triveni), cutting out the shape, stiffening the kite with bamboo sticks, decorating it, and applying the finishing touches such as sticking a small piece of paper (locally known as chippa or patti) on each corner of the kite to strengthen it. (Figs 1 & 2)

The kite industry in Gujarat comprises a chain of master manufacturers, contract manufacturers, retailers and customers.[3] The master manufacturers procure raw materials, design and are also responsible for marketing. Contract manufacturers organise skilled labour and produce kites for the master manufacturers. These kite supplies are then bought by retailers and sold to local customers. In addition to being one of the largest family-based cottage industry models in Gujarat, the kite industry exemplifies communal harmony embedded in spaces like the old city of Ahmedabad. While kite makers are largely Muslims, consumer groups comprise mainly Hindus.

The Historic City of Ahmedabad—Form and Character

The historic old city of Ahmedabad was founded on the eastern bank of the river Sabarmati in 1411 AD, by an early ruler of the Gujarat Sultanate, Ahmed Shah. It is a rich amalgamation of traditional settlement patterns, with a multicultural population comprising mainly Muslim, Hindu and Jain communities, and multiple interdependent occupational practices. These tangible and intangible features were instrumental in Ahmedabad’s recognition as a heritage city by UNESCO.[4]

According to a document released by Amdavad Municipal Corporation (AMC), the old city comprises 2,685 listed heritage buildings, with 2,236 of them residential and the rest institutional.[5] The institutions, public structures and monuments are administered by different official bodies such as AMC, Archeological Survey of India (ASI) and other community trusts. The residences are all privately owned by families or individuals. Jama Masjid, Manek Chowk and Bhadra Fort form the old city’s core, and connect to the 12 gates (darwazas) surrounding the city to districts that are further divided into settlements.

Each settlement in the old city comprises several residential units, traditionally known as pol. (Figs 3 & 4) A pol is a group of houses, typically belonging to a single large family or a group of families from the same community.[6] Accessed through a massive gate, it consists of houses, a religious institution, a chabutra (bird feeder) and a community well. Each house is about two to three storeys high, approximately five to six metres wide and 12 to 18 metres deep. The roofs are usually double pitched with a small adjoining terrace. The central feature of the house is the courtyard which not only breaks the depth to allow in light but also provides climate control, accommodates water and sanitation facilities, and acts as a private gathering space for the family. At a larger scale, these courts along with open community spaces called chowks, formed at street intersections, act as breathing spaces within the otherwise close-knit fabric.[7]

Although the city houses communities with different religious backgrounds, the planning of its settlements is based on the underlying principle of human relationships and communal living—a criterion accepted by all residents, irrespective of their belief systems.[8] The consequent cultural coherence amidst diversity plays a key role in defining the living heritage of the historic city and lends it a unique identity.

Temporary Patterns of Space Usage

Three primary components of the old city that showcase a tangible expression of Uttarayan are the streets, the otla (threshold) and terraces. While most activity on the streets is attributable to seasonal kite markets, the otla of the pol along the streets serve as extensions to kite making workshops and spaces to display kites and other ancillary items used during the festival. A series of thresholds form active edges along the street and function together to establish a dynamic realm of activity. This phenomenon can be observed at the three major kite markets in Jamalpur, Kalupur and Raipur areas in the old city of Ahmedabad. In the case of Jamalpur, the kite market seamlessly merges with the existing local market that sells fruits, vegetables, hot snacks and other everyday items. (Fig. 5) The narrow streets facilitate visual and verbal communication across kite shops and workshops lined on either side, giving a certain liveliness to the area. The home-based workshops add to this vibrancy by acting as ‘living museums’, openly showcasing the art of kite making. It is interesting to note how most of these workshops, despite being housed in small and, sometimes, oddly shaped spaces, are flexible enough to carry out work without compromising on quality. Apart from extending to the street, some workshops also tend to venture into the inner spaces of the house cluster or basements to accommodate stacks of kites and kite-making material and, at times, extra workspaces. (Fig. 6) Lack of space to exhibit their materials often leads vendors to rent shops selling other items and temporarily convert them into kite shops. Thus, the preparatory stages of Uttarayan demonstrate the capacity of optimum space utilisation and adaptability of old city spaces.

The most evident and perhaps the most relatable expression of the festival happens on the terraces. Usually, residents of the pol use terraces for drying spices and pickles, sleeping during summer nights and the occasional social gathering. The celebration of Uttarayan, however, ensures the use of terraces to their maximum potential. During the two days of the festival, they become elevated shopping streets. They are occupied from early mornings until nighttime.

During the day, there is a stark contrast between the level of activity on the inner streets and that on the terraces. Shops, except for those selling kites, remain closed and most of the house residents are on the terraces. The interconnectedness of the terraces allows close and, most of the time, direct access from one building to another, increasing the scope for interaction and multiplication of spaces. Due to the idea of shared communal living in the old city, the connected terraces become barrier-free public spaces.

Heritage as a ‘Backdrop’

The celebration of Uttarayan in the historic city of Ahmedabad is a collective social practice and is, therefore, not limited to its residents and owners. The festival, over the years, has evolved as an inclusive event that involves participation from diverse cultural groups, residents of the new part of Ahmedabad city as well as tourists and visitors from within India and abroad. This creates a fairly large influx of non-residents during Uttarayan, which generates temporary space occupancy patterns across the old city.

Heritage structures in the old city are categorised based on the level of their heritage value—highest, high or moderate. Conservation efforts by government bodies such as the AMC Heritage Department, NGOs such as the City Heritage Centre, and individual owners continue to directly or indirectly aid visitor participation in the festival. Khadia, a ward situated in the heart of the inscribed part of the city, is one of the core areas showcasing the celebration of Uttarayan at its peak. According to a survey by the Centre for Conservation Studies, CEPT University, Ahmedabad, this ward consists of 768 heritage structures, with 21 of them being particularly significant. Major heritage boutique hotels such as French Haveli, Dodhia Haveli, Mangaldas ni Haveli I and II, and numerous homestays and bed and breakfasts housed in listed properties make Khadia one of the highest concentrated heritage as well as tourist zones within the inscribed property. (Figs 8 & 9).

Uttarayan is usually promoted as a unique cultural experience to foreign guests at such places. One such facility is Jagdip Mehta’s Heritage House—a four-bedroom homestay in the Moto Suthar Wado in Khadia. The place is owned and managed by Jagdip Mehta and his family, who live on the ground floor while the upper two floors are dedicated guest bedrooms. At this homestay, Uttarayan is a family affair but it includes international guests as well as local residents. During the two days, the terrace of the house is open to the public, creating an all-inclusive, eventful environment.

Another group of non-residents, typically seen in the old city during the festival, is the kite-flying enthusiasts from the western part of Ahmedabad. While some of them come to the old city as extended family members or friends of pol residents, others obtain access through indirect contacts of houseowners to be able to enjoy the festival in old city area.

However, certain groups of people, despite wanting to use terrace spaces in the old city, do not have either of the aforementioned privileges. Keeping such groups as a target, certain houseowners temporarily rent out their terraces; this not only increases the commercial value of their heritage properties but also funds small-scale repair and maintenance costs. (Fig. 10)

Uttarayan as a Product of Cultural Tourism

Cultural tourism is based on the principle of attaching commercial value to past traditions, whether tangible or intangible, for economic gains in the present.[9] Moreover, historic urban environments have been one of the most valued tourist destinations for the past many years. In this context, the growing popularity of Uttarayan and its experience in Ahmedabad has attracted many tourists from all over the world to visit Gujarat as consumers of culture.

Although the festival has been celebrated in the old city for hundreds of years, the inscription of the walled city of Ahmedabad as a World Heritage City has considerably increased tourist footfall in the past couple of years. Additionally, government initiatives, such as the International Kite Festival, add to the agenda of bringing in more tourists into the state by investing in culture. Thus, Uttarayan has evolved from a traditional festival to a contemporary social one with global participation, and demonstrates the potential to increase economic development through the tourism sector.

The physicality of the city and its interaction with the festival aptly showcase the interdependency between material and non-material forms of cultural heritage. Here, an underlying understanding of the old city of Ahmedabad, its structure and overall social fabric, informs the exploration of Uttarayan from the perspective of space usage patterns, user groups and their corresponding ways of consuming heritage. It is impossible to study one without the other, as cultural heritage exists only in conversation with its environment.

Notes

[1] Morrison, Parkinson, and The Swadeshi Academic Council, Strings of a Timeless Tradition, 2004.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation, Ahmedabad—The First World Heritage City of India.

[5] Centre for Conservation Studies, CEPT University, ‘List of Heritage Buildings within the Historic City of Ahmadabad: Extracted from survey of buildings undertaken for UNESCO World Heritage City Inscription Dossier.’

[6] Agarwal, ‘Residential cluster, Ahmedabad: Housing based on the traditional Pols.’

[7] Ladhha, ‘Creating Breathing Spaces within the existing fabric of old cities.’

[8] Centre for Conservation Studies, CEPT University, ‘Historic city of Ahmadabad, India: Nomination dossier for inscription on the World Heritage List.’

[9] Orbasli,Tourists in Historic Towns.

Bibliography

Amdavad Municipal Corporation. Ahmedabad—The First World Heritage City of India. Ahmedabad: Government of Gujarat, 2017.

Agarwal, Kanika. ‘Residential cluster, Ahmedabad: Housing based on the traditional Pols.’ Paper presented at the 26th PLEA Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture ‘Architecture, Energy and the Occupant's Perspective’, Université Laval, Quebec City, Canada, June 21–24, 2009.

Bouchenaki, Mounir. ‘The interdependency of the tangible and intangible cultural heritage.’ Paper presented at the 14th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium ‘Place, memory, meaning: preserving intangible values in monuments and sites’, Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, October 27–31, 2003.

Centre for Conservation Studies, CEPT University. Historic city of Ahmadabad, India: Nomination dossier for inscription on the World Heritage List. Ahmedabad: Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation, 2016.

———.List of Heritage Buildings within the Historic City of Ahmadabad: Extracted from survey of buildings undertaken for UNESCO World Heritage City Inscription Dossier. Ahmedabad: Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation, 2013.

Hayllar, Bruce, Tony Griffin, and Deborah Edwards, eds. City Spaces – Tourist Places. London: Routledge, 2010.

ICOMOS. ‘A Cultural Heritage Manifesto.’ 2015. Accessed 21 October 2019. http://www.icomos-uk.org/uploads/sidebar/PDF/A%20Cultural%20Heritage%20Manifesto.pdf

Laddha, Sandhya. ‘Creating Breathing Spaces within the existing fabric of old cities.’ Paper presented at the 9th International Conference of Faculty of Architecture Research Unit (FARU) ‘Building the Future: Sustainable and Resilient Environments’, University of Moratuwa, Colombo, Sri Lanka, September 9–10, 2016.

Morrison, Skye, Mark Parkinson, and The Swadeshi Academic Council. Strings of a Timeless Tradition. Ahmedabad: Government of Gujarat, 2004.

Orbasli, Aylin. Tourists in Historic Towns. London: Taylor & Francis, 2000.

UNESCO. ‘Safeguarding communities’ living heritage.’ Accessed 21 October 2019. http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/resources/in-focus-articles/safeguarding-communities-living-heritage/.

———. ‘Social practices, rituals and festive events.’ Accessed 21 October 2019. https://ich.unesco.org/en/social-practices-rituals-and-00055.