In one of his monographs on the Angami Nagas, J.H. Hutton mentions that 'an Angami can move through the jungle as silently as a leopard.' Such descriptions of the prowess of a Naga hunter can be attributed to both the stereotype of Nagas as warriors as well as real instances of the Nagas practising hunting as an aspect of their unique social and cultural life. Although hunting is a sacred and ceremonial practice for the Nagas, it is an equally important part of subsistence.[i] J.P. Mills, in The Rengma Nagas, notes, 'All Nagas love hunting, both for the sport it gives them and for the meat it brings.'[ii]

Nagaland is home to 14 major tribes and sub-tribes[iii], each with their distinct customs, attire, languages and dialects. The Angami Nagas, who inhabit the district of Kohima, form one of the major ethnic communities in the state.

A Brief Background

The Angamis get their name from the word 'Gnamei’, a term used by the Manipuris to address them.[iv] They live in large permanent villages that are divided into smaller settlements, known as khels, separated by stone walls. The Angamis are primarily agriculturalists, and are known for the practice of terrace or wet cultivation as well as shifting or jhum cultivation. This is why the Angamis consider land their most valued property.

In addition to being agriculturalists, the Angamis are expert hunters and depend on hunting as a source of food. Their in-depth knowledge of the terrain around their villages allows them to fully utilise the natural resources available to them. A variety of traps, pitfalls and snares are made to hunt animals, birds and aquatic creatures. These are built out of materials found in the nearby jungles. Today, the Angamis use guns, which are readily available in the market and make hunting comparatively easier.

Hunting is not just an economic activity but plays an important role in the religious life of the tribe. The rites and rituals associated with the hunt highlight their belief in animism and the sacredness of nature. These rituals also play a vital role in establishing the social status of hunters in the community. The activity of hunting is crucial in determining individual and community interests. Despite a decline in its traditional methods, hunting remains a contemporary practice, with its socio-cultural and religious aspects playing an important role in the day-to-day life of the Angamis.

Traditional Hunting Methods

Hunts are usually organised in winter, when there is little agricultural activity taking place. Members of the tribe go hunting in a group or as individuals, and the hunts are male-centric, with women not allowed to take part. There is no particular age criteria that needs to be met to become a hunter. A boy who is capable of keeping up with older hunters can join the group hunt or form a group of his own.

While most animals are hunted and consumed, there are some exceptions. The Angamis refrain from hunting certain animals to avoid bad omens and self-defilement. For example, killing a slow loris (Nycticebus sp.) is considered a taboo. There are no taboos regarding the size of the animal being killed; both small- and big-game hunting are practised. Animals ranging from wildcats to deer are considered small, while gorals, bears, and tigers are said to be big animals. Porcupines of any variety are considered big animals, perhaps because they meet all the criteria of being big animals, except for size.

The rules for hunting are similar for all the villages of the Angami Nagas. They include sexual abstinence the previous night; not conversing with anyone (not even one’s wife) on the morning of the hunt; never allowing women to step over one’s legs; not making sacrilegious comments related to the hunt; abstaining from tobacco and from consuming garlic (this is known as chümeri, meaning ‘making wild animals agitated’); and passing urine or faeces while on ambush duty. Even passing flatus is strictly forbidden.

Group Hunting

Group hunting often takes place to serve a specific purpose. During the festival of Ngonyi (which marks the completion of sowing the jhum fields), members of the tribe participate in community hunts so that the whole village can have a feast. Group hunts are also organised to capture an animal (such as a tiger or a bear) that is destroying the village’s agricultural fields or preying on the cattle. In Khonoma village, even young boys and old men take part in community hunts, though they contribute very little to the success of the venture. The boys and the old men do not actively participate in ‘the hunt’ proper. Instead, they wait at a safe distance in the jungle, away from the hunting ground, and only draw near to collect their portion when the kill is distributed.

Before a community or group hunt is carried out, an elder from the group performs a ritual known as thuphi. This ritual is performed to ascertain the part of the forest where the hunt will be most successful. The elder slices some ciesenyü (a plant from the genus Artemisia), whispers a prayer and drop the ciesenyü in a particular position (no contemporary account of what is whispered for the thuphi has been found. Perhaps it is addressed to Chükhieo, the guardian god of wild animals, to gift the hunters some of his wards). The position of the fallen ciesenyü is observed and, accordingly, the elders interpret the signs and advise the hunters on where they should hunt.

After the direction of the hunt is decided, the group leaves in search of an animal. The hunters are divided into two groups: the riflemen and the men with hunting dogs. The hunting-dog party is comprised of men who know the terrain very well and are familiar with the paths regularly taken by animals. These men, also known as chasers, go to the resting places of the animals and make noises to startle them. The frightened animals respond by running away from the noise along their well-trodden paths, where the riflemen are in position for an ambush.

Individual Hunting

Individuals engaged in big-game hunts keep track of the animals, observe their behaviour and then go for a hunt. Small-game hunting is done by expert hunters. This includes the use of traps and snares of different sizes along with ketsa, a strong glue obtained from plants of the Loranthus genus.

Before participating in a hunt, the hunter’s clothes are smoked to remove his scent. On the eve of a hunt, the hunter sleeps alone in the hopes of having good dreams, believed to determine the following day’s outcome. The next day, he wakes up before dawn and walks out of the village without talking to anyone, as it is believed that talking to another person would defile him.

If he kills an animal, he is thankful and pays obeisance to the godhead by saying, ‘Terha tuo rei n kevi simo, sevo di thenuthenuo sechü tuo we’ (Your usefulness in the wild is far less than to where I’m taking you). If the animal is too big to carry by himself, he makes a sign over the animal with leaves and twigs or a cloth (any item belonging to him), symbolising ownership of the animal, and returns to the village to get more helpers for its transportation.

The kill is announced and heralded by firing shots in the air. The hunter’s friends then proclaim ‘Yalielo, [so and so], Tholieu has successfully slain [such and such] a game, come on over and relieve him of his burden’ (In Tenyidie, Yalielo means ‘relieve us of our burden’, while Tholieu literally means the man with the retracted prepuce.) On hearing the glad tidings, people respond with ‘Keta kezo’ (May there be plenty more such bounties).

When the kill is given to the hunter’s family to feast on, the menfolk are invited to partake in the chütsücü (head-meat feast), while the womenfolk partake in the chümelucü” (heart-meat feast). Each partaker pronounces the solemn blessing of ‘Tuokeprachie geicie!’ (May your every venture be thus rewarded). Another frequently used expression is ‘Tsathorüe, cüsümoe, cüsalievitie’ (Much too less, not sufficient, could eat more), meaning that plenty more feasts are wished for and that the present one is not satisfying enough.

Distribution of Meat

Chütsü: The head of the animal always goes to the person who shoots the animal first. Even if the first shooter does not kill the animal, he receives the head of the game when the animal is eventually hunted down. When a person claims this reward undeservingly, it is believed to be a bad omen. To determine exactly where the head is chopped off, the ear of the animal is pulled back, without bending the neck itself, to the point where it can stretch no more; this is where the machete strikes.

Chümei: The second person to shoot the animal, or the first person to lay their hands on the hunted animal, is awarded the chümei, a portion cut from the tail.

Meitsa: The second person to lay their hands on the hunted animal is given the meitsa. In butchery terms, the meitsa is the lower part of what is called the ‘rump’.

Meiya: This is given to the third person who claims his share over the hunted animal. The meiya is taken from the ‘round portion’ of the animal.

Misibou: Misibou is the portion given to the owner of the gun with which the animal is hunted. The right forelimb along with the first two ribs comprise the misibou. This is usually given to the same person who receives the chütsü, as Angamis hunt with their own guns. However, the chütsü recipient will not receive the misibou if he kills the animal with another person’s gun. In such cases, the misibou will invariably go to the rightful gun owner, even if he did not participate in the hunt.

The hunting dogs are given the lower portions of the limbs of the animal. In community hunts, the innards are shared between three parties: the hunting-dog party or chasers receive one-third, the riflemen receive one-third, and the butchers receive the final third. The rest of the meat is shared equally among all those who participate in the hunt. Although these rules for distributing meat are generally followed by the Angamis, they vary slightly from village to village.

Hunting Equipments

The technology for hunting is simple, and only easily available raw materials are used. Traps and snares are made using bamboo, cane and rope, while iron implements have been in use since the colonial period. Before the introduction of guns, the Angami Nagas used spears and machetes to chase big game. Guns, predominantly tower muskets, were introduced to the Nagas after the Manipur rebellion of 1891 (also known as the Anglo-Manipur war). Despite numerous confiscations, many of the guns found their way to the Naga Hills.[v] Since then, guns have become important tools for hunting. However, the traditional methods of using traps and snares still remain crucial to small-game hunting. The different types of traps and snares used are:

Kerü

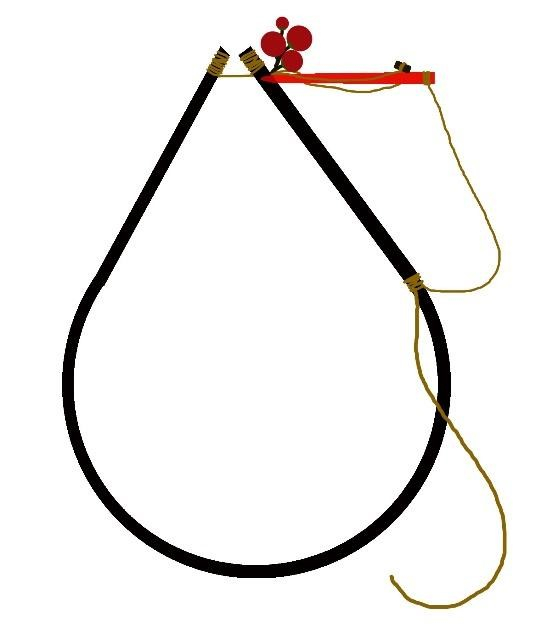

A bird trap is made out of a flat piece of bamboo with a small hole on one end. This is then bent into a ‘U’ shape, with the ends held together by a strong thread. To set the trap, the ends are tied together to form a teardrop shape to increase tension on the bamboo and to decrease tension on the thread. The thread forms a loop and is pulled out from the hole. A pencil-like stick is also wedged into the hole, upon which the loop rests. The stick serves as a platform for the bird to sit on. The bait, usually berries or larvae, is tied above the hole. When a bird lands on the trap, its weight dislodges the pencil-like stick. This releases the looped thread and traps the bird’s legs, while the bamboo’s tension pulls the loop back to its original state.

Fig 1: Kerü is a traditional trap made of bamboo and thread used to catch small birds

Misi Shüphi

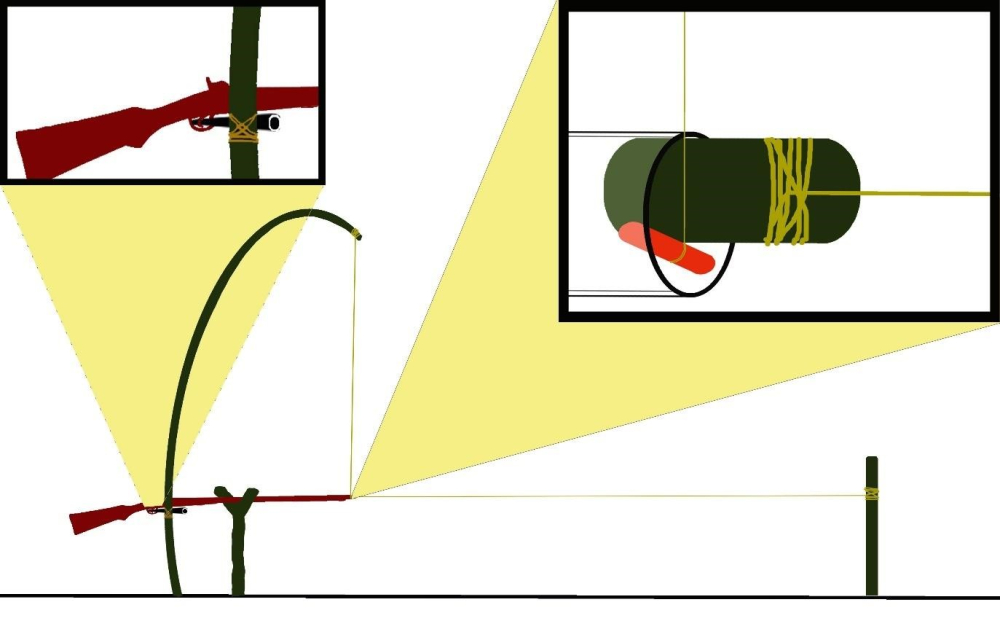

This is a land trap used mostly for big game. The trap involves the use of a rifle, cocked and pointed across the path the animal frequents. The rifle rests on two points: at the front, the barrel rests on a Y-shaped stick, and at the back, a stick goes through the trigger guard, which bears the weight of the gun. This stick protrudes horizontally from a larger branch that is bent above the gun. This is held in place by a string with a piece of wood tied to it, which is shoved into the gun barrel. A second piece of wood, tied with string, is also inserted into the barrel. The other end of this string is tied down on the opposite side of the path. This acts as the trigger or trip wire for the trap.

When the animal trips the wire, both pieces of wood wedged in the barrel come out, and the bent branch springs back and pushes the trigger, setting off the gun.

Fig 2: Misi Shüphi is a traditional trap used to hunt big game. A rifle is used in combination with pieces of wood and a string

Tsiekraba

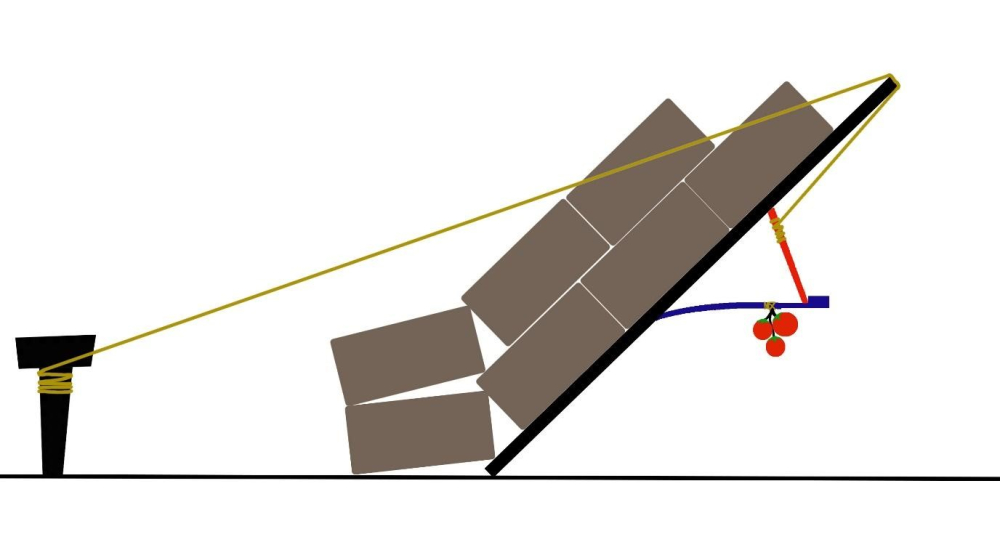

This is a land trap that varies in size according to the animal being caught. The trap involves large weights (or rocks) placed on an inclined plank. The plank holds its inclination with the help of a rope that, on one end, is tied to a short post on the ground. The rope goes over the weights and is tied to a small stick in a notch on the plank. The other end of the stick is held in place by a flexible piece of wood that is protrudes out horizontally. This also holds the bait. When an animal reaches for the bait, it releases the stick with the rope tied to it. As the rope comes off, the weighted plank falls on the animal.

Fig 3: Tsiekraba is a traditional trap that employs weights placed on an inclined plank

Seika

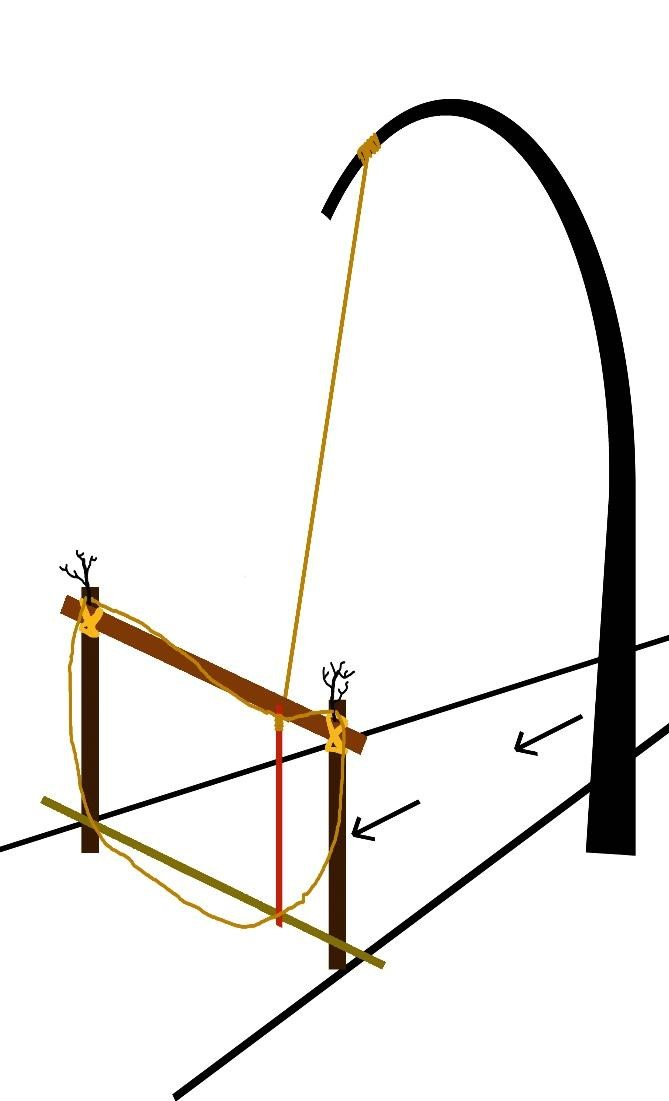

This is a land trap for medium to big game. A rope with a noose at one end and a stick tied in the middle is attached to the top of a lean but sturdy tree. The tree is bent and the noose is placed around a rectangular frame, held in place by the stick. This stick sits in a notch on the top piece of the frame. The other end of the stick is held behind the detachable bottom piece of the frame.

When an animal walks through the frame and knocks down the bottom piece, the stick is released from its notch, allowing the bent tree to straighten. This, in turn, pulls the rope, tightening the noose around the animal and trapping it.

Fig 4: Seika is a traditional trap that uses a noose to catch medium to big game

Kebie or Pitfalls

Pitfalls, made according to the size of the animal to be caught, are dug around the pathways that the animal frequents. Hardened bamboo spikes are placed vertically inside the pit and camouflaged with leaves and loose soil. Unsuspecting animals walk into the pitfall and are killed on the spikes. In order to catch the animal alive, some pitfalls are prepared without the bamboo spikes.

Socio-cultural Beliefs Associated with the Hunt

Many Angami Nagas follow an animistic faith. This is loosely defined as the belief in the presence of supernatural powers that inhabit the natural world. Due to these beliefs, a number of taboos and rituals are followed while hunting wild animals. Squirrels and rodents are considered pests who destroy agricultural products, and are not cooked inside the house or shared with women and children. As women tend to the granary, it is believed that consuming such animals will hamper the economic conditions of the village. Women also abstain from consuming most carnivores, but the reason for this is not known.

The person who hunts the animal abstains from consuming the meat. A hunter is allowed to eat the animal he kills only after he has hunted a hundred creatures. This is possibly because the Angamis believe that animals have souls and therefore hunters are forbidden from eating their game as they have killed a soul. In some villages, where hunters are allowed to partake in the meat they have hunted, it is cooked outdoors in a temporary hearth.

Hunting Beliefs and Superstitions

The Angamis consider certain events to be bad omens; when they occur, those days are considered unsuccessful. It is not considered a taboo to hunt when there is a funeral in the village, but it is believed that any expedition on that day will be fruitless. If a hunter encounters a snake on his way to the expedition, it is considered a bad omen and the day is rendered futile. Swearing is forbidden among hunters; if a man swears during a hunt, he is sent back to the village. It is also considered bad luck if a person joins the hunting group after attending a wedding. A bird named Tsieünuo sings in two forms; its melodious singing is believed to bring good luck and its other chattering form, bad luck. Pointing a gun at anything except an animal is believed to decrease the accuracy of the gun, rendering it useless and defiling the shooter’s soul. This can make him an unsuccessful hunter.

Before a hunt commences, the hunters take the blessings of the elders of the tribe. If the hunt is successful, a portion of the meat is given to the elders. The village elders bless the hunters by saying, ‘Nbu nmhi kezhie-u chülie cie’, which literally means ‘May your eyes get brighter’. This can be loosely translated to, ‘May you spot animals better’ or ‘May you have sharper eyesight’.

Dreams play a vital role in the beliefs of a hunter, despite their varied interpretations. One hunter’s account states that if he dreams of a guest visiting him from a different village, or dreams of a newlywed bride, he will have good fortune the following day. Another hunter says that if he dreams of a newborn child, his hunt is always successful. However, some dreams point to a futile hunt, such as dreaming of a person with ‘khrie’ or ‘nei’ in his/her name.

When a hunt is successful, hunters thank the spirits by exclaiming ‘Keta kezo, Terhuomia pezhie’. It is also believed that if a hunter, in his prime, is too successful, then he will not live long enough to see his old age, as he has taken too many lives.

During festivals, successful hunters adorn themselves with rami (hornbill or eagle feathers). The heads of hunted animals are used to decorate houses, and people gather to admire the hunter’s success(es). Some houses are adorned with the skulls of animals hunted by different generations of the family.

Rituals for the Hunting Dogs

There is no specific criteria for choosing hunting dogs. While most dogs are trained to hunt from an early age by their owners, some hunters have rituals performed on their dogs to make them more competent for hunting. Hunting dogs are generally treated better than regular dogs. When a hunter dies, his dog is buried along with him as his companion in the afterlife. Hunting dogs are buried and not consumed.

Rituals for a Tiger Hunt

The Angamis consider tigers to be the brothers of humankind. When a tiger is killed out of compulsion, the shooter quickly blames the gun for the kill. The corpse is kept outside the village gates, and the men re-enact hunting the tiger. The tiger is then beheaded and its head is taken to the river. The head is placed in the river and its mouth is propped open with a stick. It is believed that if another tiger wants revenge and questions the dead tiger, the latter will not be able to speak as its mouth will be full of river water. The shooter does not consume the tiger meat. For seven nights the youth of the village guard the shooter at night and sleep in his house. The shooter lies on uneven pieces of wood to ensure he does not fall asleep, as the spirit of the tiger could come at night to avenge its death.

The mortuary ritual of a tiger hunter is also performed in a slightly different manner. Some villages consider it a taboo to bury a tiger hunter within the village premises. However, other villages may not have any such restrictions. While burying the corpse, a small live puppy is buried along with it, as a sign of companionship to the soul. After the burial, a wooden sculpture of a tiger is made and placed on the grave.

Conclusion

The old practice of hunters sharing their kill with members of the tribe has slowly been eclipsed by the practice of selling the meat for monetary gain. Today, traditional hunting practices are seen as a thing of the past and do not hold much value among most Angamis. The sense of proving one’s manhood through bravery, agility, stealth and overall prowess in leading successful hunts does not have much currency anymore. Hunting methods have also changed with the arrival of modern technology.

At the same time, increasing ecological awareness and the indiscriminate killing of wildlife has led the educated class to encourage conservation and discourage hunting as a whole. In some villages, a ban on the practice has been officially imposed. In this way, the traditional hunting practices of the Angami tribe have been dying out and losing their original meaning in recent decades.

Acknowledgements

Dr David Tetso of the Department of Anthropology, Kohima Science College, and Ms Ruokuonuo Yhome, a doctoral student of archaeology in Deccan College, have been of great help in the fieldwork for and the writing of this article.

Notes

[i] Ghosh, Nagaland District Gazeteers: Mokukchung District.

[ii] Mills, The Rengma Nagas.

[iii] Vasa, ‘Traditional Ceramics among the Nagas: An Ethnoarchaeological Perspective.’

[iv] Hutton, The Angami Nagas, 14.

[v] Ibid, 84.

Bibliography

Aiyadurai, Ambika. ‘Wildlife hunting and conservation in Northeast India: A need for an interdisciplinary understanding.’ International Journal of Galliformes Conservation 2 (2011): 61–73.

Fürer-Haimendorf, Christoph von. The Naked Nagas. London: Methuen and Co, 1939.

Ghosh, B.B. Nagaland District Gazeteers: Mokokchung District. Kohima: Government of Nagaland, 1979.

Hayden, Brian. ‘Subsistence and Ecological Adaptations of Modern Hunter-Gatherers.’ In Omnivorous Primates: Gathering and Hunting in Human Evolution, edited by Robert S.O. Harding and Geza Teleki, 344–421. New York: Columbia University Press, 1981.

Hutton, J.H. The Angami Nagas. London: Macmillan and Co., 1921.

Hutton, J.H. The Sema Nagas. London: Macmillan and Co., 1921.

Jamir, W. ‘Megalithic Tradition in Nagaland: An Ethno-archaeological Study.’ PhD thesis, Department of Anthropology, Gauhati University, 1997.

Mills, J.P. The Lotha Nagas. London: Macmillan and Co., 1922.

Mills, J.P. ‘Certain Aspects of Naga Culture.’ The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 56 (1926): 27–35.

Mills, J.P. The Rengma Nagas. London: Macmillan and Co., 1937.

Sharma, T.C. ‘Prehistoric Archaeology in North-East India: A Review of Progress.’ In Eastern Himalayas: A Study on Anthropology and Tribalism, edited by T.C. Sharma and D.N. Majumdar, 102–35. New Delhi: Cosmo Publications, 1980.

Vasa, D. ‘Traditional Ceramics among the Nagas: An Ethnoarchaeological Perspective.’ PhD thesis, Department of AIHC and Archaeology, Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, 2011.