The meaning of Bhakti: etymology and history

Etymologically, the Sanskrit word bhakti is derived from the root bhaj, which would mean, 'to revere', 'to share', 'to partake', and 'to worship'. While the dominant denotation of the word bhakti would be 'devotion', it would encompass a range of meanings from attachment to love, faith and spiritual knowledge. The earliest occurrence of the word bhakti appears in the Śvetāśvataropaniṣad, which Paul Muller-Ortega dates between the 6th and 5th century BCE (Muller-Ortega 1989:27). The idea of bhakti in the sense of 'devotion to a personal god' develops entirely in the 12th chapter of Bhagavad Gītā named 'Bhakti Yoga'. The first millennium CE saw the consolidation of the ritual context of bhakti in temple worship and at homes in the rituals of pūjā. While scholars do make a distinction between the Vedic sacrificial rituals and the personal devotional worship that need not necessarily have a rulebook to adhere to, the consolidation of Vedic chanting and rituals in the temples established continuity between the Vedic hymns and emotional practices of devotion. If the Bhagavad Gītā through its bhakti yoga opened the path of liberation to all regardless of their caste or creed, it is the emotional and devotional Tamil bhakti that propelled a movement all over the subcontinent and beyond in the last two millennia. A.K. Ramanujan would place the origin of the Tamil bhakti sensibility in the later Caṅkam Tamil classical poetry Paripāṭal and the practice of pilgrimage in Tirumurukāṛṛuppaṭai (Ramanujan 1993:109a). The late Caṅkam and post-Caṅkam works of the fourth-sixth centuries (like the Paripāṭal and Tirumurukāṛṛuppaṭai) usher in a new era in Tamil culture and a new setting to Tamil religion and worship. They mark a change from the nature landscape (tiṇai) of the Caṅkam works to the temple or sacred landscape of the bhakti hymns, a different genre of poetry.

Champakalakshmi views the formative centuries of Tamil bhakti poetry as the unique and watershed era for the entire subcontinent. Arguing that the South Indian regions show a remarkable difference in the socio-political and religious configurations in the period of transition, Champakalakshmi writes:

For the Deccan and Andhra regions, it marks a clear change towards Brāhmanical dominance, but for Tamiḻakam, it was a period of the ascendancy of the Śramaṇas, that is the Buddhists and, more particularly, the Jains. This period is often described as the 'dark age', presumably for the Brāhmaṇical tradition, which seems to have remained in relative obscurity. A conspicuous lack of Brāhmaṇical sources may be seen till the beginnings of the bhakti poetry and bilingual inscriptions which look back at the 'dark age' as the Kali age, undoubtedly due to the ascendancy of the Śramaṇas, especially, the Jains. The Kaḷabhras of this period, who are believed to have subverted the socio-political domination of the Sangam ruler (the Cēra, Cōḷa, and Pānḍya) are also described as Kali araśar (evil kings). Two post-Sangam works focusing on the Purāṇic religion and the first stone inscription referring to Brāhmiṇical institutions dated to AD 500 may be interpreted as marking this transition. (Champakalakshmi 2011:15a)

The historical development of bhakti is complex both in the Tamil country and its subsequent spread throughout the subcontinent. While the first transformation from the Caṅkam period brought in a new regional synthesis of Purāṇic forms with the northern Sanskritic elements assuming a dominant position, in the subsequent early medieval period (400–600 CE and 600–1300 CE) Tamil bhakti developed into an ethical and moral principle against the caste system. This progression might not surprise us if we were to place bhakti in the social-political contexts of its time. Having unseated the Śramaṇic religions (Jains and Buddhists) from their imperial political power and having revived the popularity of Śaivism and Vaiṣṇavism, the political role of bhakti expanded to assign a central role to Vedic brāhmaṇas or Caturvedis along with temple administrators of the brahmadeya sabhā in the social and religious spheres. The Cōḷa kings consciously built and promoted grand temples, provided land grants to Caturvedis along with special privileges, and bhakti served as their ideology to consolidate the state-religion/temple nexus. Expressing a strong criticism of Varṇa hierarchy, the bhakti saints/poets placed bhakti above caste hierarchy, denouncing the Dharmaśastras that accorded superiority based on Kula and Gotra (Champakalaksmi 2011:1-50b).

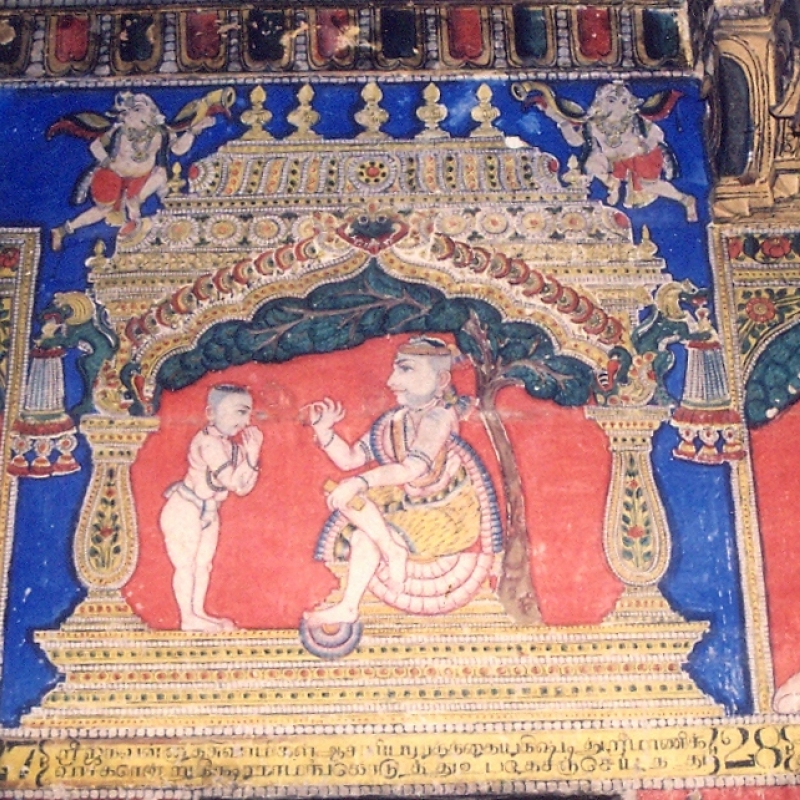

The Cōḷa kings shared the notion of the divine origin of royalty and their birthright to rule from their predecessors, the Pallava dynasty rulers of the sixth century. The age of the epics in the North Indian landscape under the aegis of dynasties such as the Śakas, Kuṣanas and the Guptas (3rd century BCE to 5th century CE) saw the alliance of state and religion through the uses of propagation of theism, temple construction and iconography that would cast gods and kings in identical images of power and glory. This paradigm of authority as a practice in vogue shifted to the Pallavas with the passing of the Guptas and their immediate successors in North India. According to one of the early inscriptions, the Pallava king performed various Vedic sacrifices. These ceremonies relatively new to the local population were probably seen as largely symbolic, emphasising the power associated with ritual in Sanskritic culture. The Pallava royal temple carried assertions of royal authority in various ways, such as lengthy inscriptions narrating the history of the king or sculpted panels depicting the mythology of the deities drawn from the Purāṇas, the Mahābhārata and Rāmāyaṇa (Thapar 2002:360). A.K. Ramanujan describes the Pallava period as the historical time when the two 'classicisms' of India, that of the Guptas and that of Tamil classical poetry seem to have met (Ramanujan 1993:105b). For 300 years (6th century CE to 9th century CE), the Pallavas and the Pāṇṭiyas dominated the Tamil region and waged war against each other and other kingdoms in the Deccan. In the midst of wars, arts and culture thrived, and chief among them were temple architecture and bhakti poetry.

Up to the 12th century, with the Cōḷa and Pāṇṭiya kings embracing Śaivism and the Cēra kings adopting Vaiṣṇavism, the temple became the centre of social and religious power in South India. Both the Śaivite and Vaiṣnavite bhakti poets wandered from one temple to another singing the praises of the presiding god and extolling the virtues of Śiva and Viṣṇu, especially their grace (aruḷ) and love (aṉpu) (Peterson 1991). The Śaiva saints celebrate 274 holy temples; the Vaiṣṇavas, 108, of which 106 are terrestrial, and two are celestial, that is, Viṣṇu's paradise Vaikuntam, and the Ocean of Milk where he sleeps. The 274 Śaivite temples consecrated by the bhakti poets were called pāṭalpeṛṛa sthalaṅkaḷ and the 108 Vaiṣṇavite temples were considered to be made auspicious, divyadeśams, by the hymns of Aḻvārs. Because of the hymns of the Vaiṣṇavite bhakti saints, the 108 divyadeśams came to be known as the maṅkaḷa sāsanam peṛṛa sthalaṅkaḷ. With the expanded networks of temples, the Tamil landscape became the sacred geography of Hindu culture completely wiping out the Śramaṇic religions, Jainism and Buddhism. The concept of bhakti came to refer to those forms of worship associated with a temple, in which ritual is performed to an icon (deva-pūja) and viewing (darṣan) of the God's representative icon is supreme. In this form, bhakti can include pilgrimage to holy temples and places (tīrtha), the practice of vows and observances (vrata), devotional singing (bhajan), participation in the festivities, and performing dramas, dances, musical recitals, storytellings (kathākālaśepam) and other forms of worship in the congregational settings of the temples. Bhakti is believed to enable the devotee to gain communion with God, to be eternally in God's presence as an attendant, or even to obtain complete union with God (sājujyal). Expressions ranging from 'wordless bliss' to 'descendence into madness' or 'intoxication' and 'climbing the mountain' (malai ēruṭal) to 'height of anger' (āvecam) describe the experience of the devotee's communion with the God in the bhakti poetic tradition. Trance or possession came to be the expressive public behaviour of the devotees, and it signifies the inner psychological experience of the communion (Shulman 2002, Muthukumaraswamy 2012).

Hart distinguishes the passionate devotion of the Tamil bhakti from that of the Bhagavad Gītā where the emphasis is on discipline and control. The Tamil bhakti verses express and idealise violent and intense emotional involvement with a personal God, accompanied by a sense of despair and helplessness (Hart 1976:343). Tiruviḷaiyāṭārpurāṇam, an 18th-century compilation of 64 divine exploits of Lord Śiva, narrates extreme forms of devotional lives led by his devotees. Kaṇṇappa Nāyaṉar would pluck out his eyes and place them on the bleeding eyes of the Śiva linga he was worshipping. Siṛuthoṇṭa Nāyaṉar would cook his child as food for Lord Śiva, who visits his home in the disguise of a Śaivite devotee. While such extreme acts are plentiful in the bhakti literature, the emphasis is always on bhakti being the supreme liberator, and that is to be achieved through devotion and faith in the truest sense of the terms. Bhakti, in this sense, connotes a devotee's intensely intimate experience with the personal deity (iṣṭa devata). Over the centuries, bhakti has thus come to occupy both the personal sphere of home and the public arena of the temple, arts and even the marketplace.

The collection and the canonisation of the Śaiva and the Vaiṣṇava bhakti poetry in the 10th century led to the spread of bhakti as a mass movement. Cuntarar's (between 780–830 CE) work, Ārūr Tiruttoṇṭattokai, originated the Śaiva canon. In his poem, Cuntarar mentioned 62 nāyaṉmārs (saints of Tamil Śaivism). He was added as the Cuntaramūrtttināyaṉar, and a total of 63 nāyaṉmārs decorated as the saints of Śaivism. Nampi Āṇṭār Nampi (1080–100 CE) arranged and anthologised the hymns of Campantar, Appar, and Cuntarar as the first seven holy books and added Māṇikkavācakar's Tirukkōvaiyār and Tiruvācakam as the eighth book. Tirumūlar's Tirumantiram, 40 hymns by two other poets, Tiruttoṇdar tiruvantāti and Nampi's hymns constitute the ninth to eleventh books of the Śaivite canon respectively. Cēkkiḷār's Periya Purāṇaṃ (1135 CE) became the twelfth Tirumuṛai and completed the Tamil Śaivite bhakti canonical literature. This body of works represents a huge corpus of heterogeneous literature covering nearly 600 years of religious, literary and philosophical developments. Kāraikkāl Ammaiyār's songs (500 CE) and the compositions of the Pallava King Aiyaṭikal Kāṭavar Kōn (670–700 CE) were the earliest in the Śaivite canon and Cēkkiḷār's Periyapurāṇam (early 12th century) would be the latest.

Nātamuṉi (10th century), who is considered to be in the line of the very first Vaiṣṇavite ācāryas (teachers), compiled the Vaiṣṇavite bhakti poetry into a huge compendium called Nālāyirativyaprapantam, 'The Four Thousand Divine Works'. The earliest of Vaiṣṇavite poet-saints, Poykaiāḷvār, Pūtatāḷvār and Pēyāḷvār, belong to 650 to 700 CE. The Vaiṣṇavite canon consists of the works of 14 poets, out of which 12 are considered as āḷvārs.

The twelve books of Śaivite Tirumuṛai

|

Number of the book |

Poet-Saint |

Name of the Work |

|

1 |

Campantar |

Tēvāram I |

|

2 |

Campantar |

Tēvāram II |

|

3 |

Campantar |

Tevāram III |

|

4 |

Tirunāvukkaracar |

Tevāram IV |

|

5 |

Tirunāvukkaracar |

Tevāram V |

|

6 |

Tirunāvukkaracar |

Tevāram VI |

|

7 |

Cuntarar |

Tevāram VII |

|

8 a |

Maṇīkkavācakar |

Tiruvācakam |

|

8 b |

Maṇīkkavācakar |

Tirukkōvaiyar |

|

9 a |

Tirumāḷikaitetēvar |

Tiruvicaippā 4 patikam |

|

9 b |

Cēntnar |

Tiruvicaippā 3 patikam |

|

9 c |

Karuvūrttēvar |

Tiruvicaippā 10 patikam |

|

9 d |

Pūntuurutti Nampi |

Tiruvicaippā 2 patikam |

|

9 e |

Kāṇṭarātittar |

Tiruvicaippā 1 patikam |

|

9 f |

Vēṇāṭṭaṭikal |

Tiruvicaippā 1 patikam |

|

9 g |

Tiruvāliyamuntaṉar |

Tiruvicaippā 4 patikam |

|

9 h |

Puruṭōṭṭama Nampi |

Tiruvicaippā 2 patikam |

|

9 i |

Cētiriyar |

Tiruvicaippā 1 patikam Tiruppallāṇṭu |

|

10 |

Tirumūlar |

Tirumantiram |

|

11 a |

Tiruvālavāyuṭaiyar |

Tirumukappācuram |

|

11 b |

Kāraikkālammaiyār |

3 works (Aṛputtatiruvantāti) |

|

11 c |

Aiyaṭikal Kāṭavar Kōn |

Kṣēttriratiruveṇpa |

|

11 d |

Cēramaṉ Perumāl |

3 works |

|

11 e |

Nakkīratēvar |

9 works (Tirumurukāṛṛupaṭai etc) |

|

11 f |

Kallāṭatēvar |

Kaṇṇappatēvartirumaṛam |

|

11 g |

Kapilatēvar |

3 Works |

|

11 h |

Paraṇatēvar |

Civapermaṉ tiruvantāti |

|

11 i |

Iḷamperumāṉ Aṭikaḷ |

Ciperumavaṉ tirumummaṇikkōvai |

|

11 j |

Atirāvaṭikaḷ |

Mūttappiḷḷaiyar tirumummaṇikkōvai |

|

11 k |

Paṭṭiṉattaṭikaḷ |

4 works |

|

11 |

Nampi Āṇṭār Nampi |

10 works Tirttoṇṭatiiruvantāti etc. |

|

12 |

Cēkkiḻār |

Periyapurāṇam |

Vaiṣṇavite bhakti hymns Nālāyirativyaprapantam

| Number of the book | Poet Saint | Name of the Work |

|

|

Mutalāyiram ‘The First Thousand’ |

|

|

1 |

Periyāḻvār |

Tiruppallāṇtu |

|

2 |

Periyāḻvār |

Tirumoḻi

|

|

3 |

Āṇṭāḷ |

Tiruppāvai |

|

4 |

Āṇṭāḷ |

Nāycciyārtirumoḻi |

|

5 |

Kulackarap Perumāḷ |

Tirumoḻi |

|

6 |

Tirumaḻicai Āḻvār |

Tiruccantaviruttam |

|

7 |

Toṇṭaraṭippoṭi Āḻvār |

Tirumālai |

|

8 |

Toṇṭaraṭippoṭi Āḻvār |

Tiruppaḷḷiyeḻuci |

|

9 |

Tiruppāṇāḻvār |

Amalaṉatipirāṉ |

|

10 |

Maturakavi |

Kaṇṇinṉun ciṛuttāmpu |

|

|

Iraṇṭāṃ āyiram ‘The Second Thousand’ |

|

|

1 |

Tirumaṅkai Āḻvār

|

Periya Tirumoḻi |

|

2 |

Tirumaṅkai Āḻvār |

Tirukuṛuntāṇṭakam |

|

3 |

Tirumaṅkai Āḻvār |

Tiruneṭuntāṇṭakam |

|

|

Mūṉṛām āyiram Iyaṛpā ('The Third thousand') |

|

|

1 |

Poykai Āḻvār |

Mutal Tiruvantāti |

|

2 |

Pūtam Āḻvār |

Iraṇṭāṃ Tiruvantāti |

|

3 |

Pēy Āḻvār |

Mūṉṛām Tiruvantāti |

|

4 |

Tirumalicai Āḻvār |

Nāṉkām Tiruvantāti |

|

5 |

Nammāḻvār |

Tiruviruttam |

|

6 |

Nammāḻvār |

Tiruvāciriyam |

|

7 |

Nammāḻvār |

Periya Tiruvantāti |

|

8 |

Tirumaṅkai Ālvār

|

Tiruveḻukkūṛṛirukkai |

|

9 |

Tirumaṅkai Āḻvār

|

Ciṛiya Tirumaṭal |

|

10 |

Tirumaṅkai Āḻvār

|

Periya Tirumaṭal |

|

|

Nāṉkām āyiram 'The Fourth Thousand' |

|

|

11 |

Nammālvār |

Tiruvāymoḻi |

|

|

Appendix |

|

|

12 |

Tiruvaraṅkamutaṉār |

Irāmāṉucaṉūṛṛantāti |

It is important to note here that each of the hymns of the āḻvārs has a prefatory stanza called taṉiyaṉ, and these compositions are partly in Sanskrit.

The canonization of the Tamil Vaiṣṇavite hymns influenced the Bhagavatha Purāṇa, a tenth-century text storytellers predominantly used in their religious discourses throughout the region (Thakkar 1966). In a self-reflexive way, Bhāgavatha Purāṇa mythologised the birth and dissemination of bhakti in a succinct story:

Bhakti, a Devī born in Drāviḍa deśa, along with her two sons, Jñāna and Vairāgya, started on a walking tour to Gokula and Vṛndāvana, and she meets sage Nārada on the way. She says that she was born in the Drāviḍa deśa, came of age in Karnataka and she was well respected in Maharashtra but coming into Gujarat, she became old and feeble. On reaching Vṛndāvana (the childhood home of Kṛṣṇa) she became young again and filled with beauty. However, her sons continued to remain old. She requested Nārada to turn them young again. Nārada read out the Vedas, Upaniṣads and Bhagavad Gītā, but they had no effect. Nārada soothes Bhakti and assures her that this evil age has at least one advantage: that it is only in this worst of all possible times, the Kali Yuga, that a person can attain the supreme goal by reciting the name and speaking about the glory of Viṣṇu. Most important, he says, one cannot get even with austerities (tapas), yoga, or meditation. Then he read the Bhagavatha Purāṇa to them and the sons of Bhakti Devī became young again. (Puranic Encyclopaedia: 115)

Analysing the much-quoted bhakti's story in contemporary scholarship, Vasudha Narayanan suggests that the story is indicative of how bhakti has come to occupy a distinguished place among the many Hindu traditions in preference to the other paths to liberation. Elucidating further, Narayanan cites the extensive use of vernacular languages by the bhakti poet-saints and the fact they came from all social classes as the reasons for the immense popularity and the spreading of bhakti as the mass movement (Narayanan 2012). Texts like Bhāgavatha Purāṇa and religious teachers like Rāmānanda, Jñāndev (13th century), Tukārām (1598–1649), Mīrābāī (1450?–1547) became the famous proponents of bhakti in North India. The timeline of bhakti's prominence in different in Indian languages would look like this: Tamil: 6th to 9th century; Kannada: 10th century; Gujarati: 12th century; Kashmiri: 14th century; Maithili: 14th century; Assamese: 14th to 15th century; Bengali: 14th to 15th century; Oriya: 15th century; Maharashtra: 16th century; and Braj and Avadhi: 16th century.

About the 12th century, Vaiṣṇavism divided itself into four major schools of thought or Saṃpradāyas. They are Śri-, Brahma-, Rudra-, and Sanakādi- Saṃpradāyas, led by philosopher-theologians Rāmānuja, Madhva, Viṣṇusvāmin (Vallabhācārya) and Nimbārka. Against the monistic teaching of non-duality (Advaida-vāda) of Śaṅkara and its intellectual way of seeking eternal knowledge (jñāna) and liberation, all these schools agreed in exalting bhakti as the sole religious attitude of love and service towards a personal God. Rāmānuja (1017–1137 CE) in his Gītābhāsya famously argues that bhakti yoga as advocated by the Bhagavad Gītā is a way that builds on jñāna yoga and bhakti's path leads to meditation and knowledge. Rāmānuja's highly influential teachings and his Śri Saṃpradāya school of thought provided bhakti with an intellectual basis. Though Rāmānuja established a number of Viṣṇu-Lakṣmi temples, theoretically his doctrine and that of the other schools did not single out any particular incarnation for worship, but, as the faith was personal in ardour, the followers of Śri Vaiṣṇava Saṃpradāya preferred Viṣṇu and Rāmā. In North India, the other three schools of Madhva, Vallabha and Nimbārka adored Kṛṣṇa. The Bhāgavatha Purāṇa popularly established the supremacy of Krṣṇa against the exuberant and luscious background of epic, myth, theology, and mystical eroticism. The Krṣṇa-Gopi legend blooms in its full splendour in the Bhāgavatha Purāṇa with the glorification of bhakti and Kṛṣṇa-līlā. The Kṛṣṇa of Śrīmad Bhāgavatham is so different from the Kṛṣṇa of the Bhagavad Gītā. Regarded as the supreme scripture of the mediaeval Vaiṣṇavism, Śrīmad Bhāgavatham presents a youthful Kṛṣṇa utterly abandoned to the romantic love of the gopis and a vivid picturization of the eternal sports of Kṛṣṇa in Vṛndāvana. Of the mediaeval schools, Vallabhācāris and Nimbārkas recognise Rādhā as Kṛṣṇa's divine power and spouse in the divine sport. The perfect couple of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa and Rādhā's prema bhakti came to characterise Indian performing arts ranging from Rāsa Līlā to Bharatanatyam and Manipuri dance.

The parallel development in the Śaivite bhakti movement was two-fold. One was the proliferation of Śaiva Āgama literature that integrated temple worship, architecture and rules for daily pūja and festivities. Recent scholarship (Sanderson 2009, Davis 2009) dates the integration of Sanskrit and Tamil, Āgamas and Vedas, temple worship and householder's practice in Tamilnadu to the 12th century when (the proverbial author of the authoritative Āgama text Kriyakramadyotikā) Aghoraśiva took up the task of amalgamating Sanskrit and Tamil Siddhānta. Strongly refuting Śaṅkara's heritage of monist interpretations of Siddhānta, Aghoraśiva brought a change in the understanding of the Godhood by reclassifying the first five principles of Śaiva Siddhānta namely Nāda (sound), Bindu (the bodily mystical point where fluid of immortality flows), Sadāśiva (the ever-revealing grace of the primal soul), Èsvara (Supreme God) and Suddhavidya (pure knowledge), into the category of pācam (bondage), stating they were effects of a cause and inherently unconscious substances, a departure from the traditional Vedantic teaching in which these five were part of the divine nature of God.

Aghoraśiva was successful in preserving the Sanskrit rituals of the ancient Āgamic tradition. To this day, Aghoraśiva’s Siddhānta philosophy is followed by almost all of the hereditary temple priests (Śivācāryas), and his texts on the Āgamas have become the standard ritual manuals. His Kriyakramadyotikā is a large work covering nearly all aspects of Śaiva Siddhānta ritual, including initiation, worldly duties, householder's meditation and worship, and installation of deities. In the 13th century, Meykaṇṭatēvar and his student Aruḷnandi Śivācārya further spread Tamil Śaiva Siddhānta. Meykaṇṭatēvar wrote Civa-ñāṉa-pōtam ('Understanding of the Knowledge of Śiva') and Aruḷnandi Śivācārya wrote Śiva-jñāna-siddhiyār ('Attainment of the Knowledge of Śiva'). Umāpati's Śivaprakāśam ('Lights on Śiva') in the 14th century, Śrīkaṇṭha's commentary on the Vedānta-sūtras (14th century), and Appaya Dīkṣita's commentary thereon established the continuity of the tradition. Meykaṇṭatēvar's Civa-ñāṉa-pōtam and subsequent works by other writers laid the foundation of the Meykaṇṭatēvar's Tamil tradition, which propounds a pluralistic realism wherein God, souls and the world are coexistent and without beginning. Śiva is an efficient but not material cause. They view the soul’s merging in Śiva as salt would dissolve in water, an eternal oneness that is also twoness (Muthukumaraswamy 2015:188).

The Āgamas prescribed for the installation of the icons of Śaivite bhakti saints in the Śiva temples and the celebration of the bhaktōṛsavam focusing on the nāyaṉmārs. The first of the 63 nāyaṉmārs, Candikēsvara was the one who found a place of sculptural honour on the outer walls of the sanctum sanctorum of the Śiva temples. Gradually stone and bronze statues of all the 63 nāyaṉmārs found places of honour in the inner corridor of the Śiva temples (Lakshmi 1994).

The second development within the Śaivite bhakti movement was the protest against the establishment of public religion with grand temples, sacred texts, performances and hierarchical social organisation as evidenced by the Vīra Śaiva sect in 12th-century Karnataka. Between the 10th and the 12th century Karnataka witnessed an explosive growth of religious lyrical free verse called vacanas. In Kannada, vacana would mean 'saying or an utterance'. The impassioned vacanas of the Vīra Śaiva poet-saints established a tradition of vacanakāras in Kannada, and nearly 300 poets continued this tradition of religious poetry. Basavaṇṇa, Dāsimayya, Allama, and Mahādēviyakka were the chief exponents of the vacana tradition. A.K. Ramanujan wrote, 'Vacanas are literature, but not merely literary. They are a literature in spite of itself, scorning artifice, ornament, learning, privilege; a religious literature, literary because religious; great voices of a sweeping movement of protest and reform in Hindu society; witnesses to conflict and ecstasy in gifted mystical men. Vacanas are our wisdom literature. They have been called the Kannada Upaniṣads. Some hear the tone and voice of Old Testament prophets or the Chaung Tzu here. Vacanas are also our psalms and hymns. Analogues may be multiplied. The vacanas may be seen as still another version of the Perennial Philosophy' (Ramanujan 1973:12). Vacana poets strived towards an unmediated vision of the self which is a refinement of the bhakti poetic form, language, and thought. They were against all forms of hegemonies including casteist and sexist oppressions. Their devotion to their personal Gods endowed them with power to speak freely against scriptures, Brahminism, Jainism and even other Śaivite practices. The movement reached its peak under the leadership of Basavaṇṇa, a Brahmin rebel who was a minister in the regime of Kālacūryas. After a huge gathering of vacanakāras from diverse caste backgrounds under the leadership of Basavaṇṇa, violence broke out between the state and the poets. Subsequently, the Kālacūrya King was assassinated, and Basavaṇṇa passed away mysteriously. The movement went underground nearly for a century, only to receive royal patronage under the Vijayanagara empire in the 14th century (Shivaprakash 1999).

Researchers have identified similarities between the style and contents of two women bhakti poets, Āṇṭāḷ of Tamil Vaiṣṇavite poetry and Mahādēviyakka of Kannada Śaivite vacana tradition (Tyagi 2008, Jagannathan 2009). The Vaiṣṇavaite poems of the Āḻvārs continued to impact the bhakti poets of the Northern India (Mohammada 1975). In the late classical period, from the 12th through the 17th centuries, major bhakti poet-saints emerged in languages such as Bengali, Hindi, Telugu, and Marathi. The major difference between the South Indian bhakti poets and their counterparts in North India is that while the Southerners sang their devotions to a deity of a particular place concerning the general divinities of Śiva or Viṣṇu, the Northerners sang in praise of a particular avatār of Viṣṇu such as Rāmā or Kṛṣṇa. The devotees of Śri Vaiṣṇava Sampradāya consider the deity in the temple a manifestation of Viṣṇu in absolute terms. So the Āḻvārs sang the praise of Viṣṇu who is indistinguishable from his many avatārs and also the icon in the temple, whereas for Sūrdās it is the avatār of Kṛṣṇa and for Tulsidās it is the avatār of Rāmā who is the focus of bhakti.

The Bhāgavatha Purāṇa further defined nine categories of bhakti behaviour that would characterise the life and works of a bhakti poet-saint and a commoner devotee in North India. These categories are 1. śravaṇa (hearing about the divine being); 2. kīrtana (singing about the deity); 3. smaraṇa (remembering the stories and activities of the divine one); 4. pādasevana (serving the divine feet of the deity); 5. arcana (worshipping an iconic incarnation of the deity); 6. vandana (prayer; reverence); 7. dāsya (the desire to serve); 8. sākhya (friendship); and 9. ātmanivedana (surrendering oneself). In the Swaminarayan movement in Gujarat, the highest form of bhakti is attributed to a chaste wife who practises her devotion to her husband along with the nine kinds of bhakti to God.

As bhakti progressed from being a religious doctrine to a life-guiding principle, it lost some of its original characteristic of being intoxicated and mad in experiencing God. Even when the 12th century Sanskrit poem the Gītagovinda extolled the love of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa and contributed hugely to the bhajan singing traditions across North India, the passionate love embedded in bhakti became subdued and sublime. The madhura bhava, the sweet love between Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa in the conceptualisations of Caitanya and others became romantic love devoid of trance. Vallabhācārya (about 1500 CE) in his Subodhinī, his commentary on the Bhāgavatha Purāṇa theorised that all ordinary/worldly (laukika) desires are extinguished in the one transcendent/extraordinary (alaukika) desire, bhakti, the desire that is unconditional love for the Supreme Self (ātmakāma) (Redington 1992). In 15th-century Assam, Śaṅkardev (1449–1568) created new forms of music (Borgeet), theatrical performances (Ankia Naat and Bhaona), dance (Sattariya) and a new literary language, Brajavali. His philosophy of Ekasarana Dharma (surrender to One God) privileges dāsya bhava, an attitude of a slave to God as the bhakti and completely shuns romantic love. Unlike the Gaudia Vaiṣṇavism of Bengal, in Śaṅkardev's neo-Vaiṣṇavite bhakti movement Rādhā is not worshipped at all. In Vallabhācārya's elaboration, bhakti, the love of God is transformed into an end in itself and not as a means to something else. His philosophy of pure monism (Suddha Advaita) obliterated the difference between the creator and the created, and introduced selfless service to Kṛṣṇa, Sevā, as the main practice of bhakti. His followers in the Puṣti mārg expanded the idea of Sevā as a practice of ritual worship to service to worthy causes.

Historians of the bhakti movement credit its practices for the ability to merge and evolve concepts of love and God from other religions and local conventions. From the 15th century onwards, if the bhakti practices changed from elaborate temple worship and the ability to compose striking aphorisms to the simple chanting of the names of God, they also accommodated concepts of God from other religions. Bhakti's cultic theism developed with the selective syncretism of Buddhism and Jainism in the early phase and offered a popular alternative to them. The universality of God crossing the boundaries of religions and eschewing blind faith were two other themes that dominated the syncretic poetry and teachings of Lal Ded (1320–1392), Kabīr (15th century) and Guru Nanak (1469–1539). Along with Hindu thoughts, Islamic Sufi poetry influenced their ideas and teaching. Lal Ded's vastun or Vachs were the earliest mystical verses in the Kashmiri language, and they revealed influences of Kashmir Śaivism and Sufi mystical poetry. Kabīr's poetry has much in common with the teachings of Sufi Muslim teacher Dādū Dayāl (1544–1603) and with Guru Nānak, revered by the Sikhs as their founding teacher. While the bhakti of Kabīr is towards the formless and abstract God (Nirguṇa Brahman) other poets of the same period Sūrdās (1483–1563) and Tulsīdās (1543?–1623) express their devotion to a personal deity (Saguṇa Brahman). Tulsīdās' Rāmacaritmānas revels in its beautiful poetry, and it has influenced millions of Rāma devotees in the Hindi heartland. What should be the devotee's choice between the Nirguṇa Brahman and Saguṇa Brahman is a crucial debate in the history of bhakti movement and it has led to critical philosophical discourses and formation of sectarian practices within Hinduism. Similarly, another key debate within the history of bhakti movement is the perceived tension between intellection (Jñāna Mārga) and emotion (Bhakti Mārga) in knowing the ultimate nature and reality of God. While many theologian-philosophers of Hinduism had resolved this tension by offering sophisticated arguments to prove Jñāna is Bhakti and Bhakti is Jñāna, many Vedāntins and Śaiva Śiddhantins persisted with their preference for Jñāṇa Mārga and deplored bhakti's emotional path as an impediment to the realisation of God.

Despite the critical debates and the sectarian tendencies, bhakti continues to be a unifying force among Hindus, providing a social fabric that crosses over castes and languages. Bhakti's social structure kept Hindu communities together during periods of tumult. Mahatma Gandhi effectively invoked the Rāmarājya to signify free and independent India and used the congregational settings of the bhakti bhajans to steer the nationalist movement. Balagangadhar Tilak infused Hindu festivities such as Ganesh Chaturthi with nationalist fervour. Rabindranath Tagore and Subramanya Bharathi wrote poems of intense nationalism inheriting the idiom and aesthetics of bhakti. During the independence struggle, all the folk performing arts of India transferred their inherent bhakti aesthetics into forms of resistance against the British. It is no exaggeration to say that independent India was born on the bedrock built by the culture and heritage of bhakti.

Post-Independence India witnessed another resurgence of Hindu bhakti characterised by the renovation of temples, renewed interest in pilgrimages, festivals and temple rituals. The growth of electronic media such as audio video cassettes, television channels and the Internet made Sanskrit texts and mantras, and various devotional materials accessible and available to audiences across languages and regions. Epics such as Mahābhārata and Rāmāyaṇa were available as television serials in all Indian languages.

Internationally, the most prominent bhakti organisation is the International Society of Kṛṣṇa Consciousness (ISKCON) known as the Hare Kṛṣṇa movement. Launched in 1966 in New York by Bhaktivedanta Prabhupada, ISKCON derives its emotional and devotional chanting from the teachings of Caitanya Mahāprabhu.

The dissemination of the figure of bhakti poet-saints and their texts

The bhakti poet-saints are quite lively and interesting historical figures in the cultural and religious landscape of India. The bhakti poets are not saints in the strictest sense of the term. They are poets, wanderers, mystics, renouncers, sages, philosophers, godmen and godwomen, but they are not saints. The bhakti poets who had respectful epithets such as Nāyaṉmār (chieftains of Śiva), Āḻvāṛ (one who is immersed in the bhakti of Viṣṇu) and Das (devotee). The early translators of bhakti poetry translated these Indian terms to 'Saints', and the use continues with an Indian connotation of the bhakti poets being equated with Ṛiṣi (sage or seer). The reason we need to make this distinction is to clarify the cultural meanings we invest in the figure of bhakti poets. Although Śaivite and Vaiṣnavite traditions recognised the authority of the bhakti poets and inducted them into the pantheon of teachers, it was never an institutional process. Their canonization was always through literary processes of compilation, hagiographies, commentaries and sculptural representations of their images in the temples and public squares. Oral traditions helped to spread the mythologies of their lives and deeds. Their authority is based on religious experience, and they composed songs of love in people's languages for God in manifest forms (Saguṇa) such as Kṛṣṇa, Rāma, Śiva or the Devī as well as God beyond the form (Nirguṇa). Among the bhakti poet-saints were women and members of the so-called low castes. Their biographies are filled with suffering since their lives invariably ran a course against authority and power.

The diversity of social classes bhakti poets hailed from is breathtakingly large. While Sūrdās was a blind Kṛṣṇa devotee, Kabīr was an iconoclastic weaver devotee of the formless God. While Raidās was a leather worker, Mīrābāi was a Rajasthani princess. Tirumṅkai Āḻvār was a thief, Kaṇṇappa Nāyaṉar was a hunter, and Māṇikkavācakar was a minister in the Pāṇṭiya court. A.K. Ramanujan wrote:

But, unlike the Buddha, the Hindu saints do not appear alone, they seem to appear in droves, in interacting groups of three or four in these early times. They often form a composite saint, each taking on a different face of the religious experience. For instance, among the Vīraśaivas, if Basava is the struggling reformer-saint, Allama is metaphysical, imperious, the Master (prabhu); Mahādevī, the woman-saint, is in love with god, and god to her is a sensual and aesthetic experience; still another saint Dāsimayya, is fierce, even crude at times, and hates those who do not see what he sees; Cennabasava is the theologian, aptly the nephew/ son-in-law of Basava. (Ramanujan 1999:281a)

That is probably why the compilations and hagiographies tried to present the bhakti poets in a holistic manner, so that it is a position of aspiration that one can achieve by leading a dedicated religious life. The appearance of the figure of a bhakti poet-saint in the history of Indian culture is an aspirational one signifying investment of values of a group of people in a particular societal context. A.K. Ramanujan mapped a structural pattern in the lives of women poets, explaining different choices available to women poets at various crucial stages of life. His map consisted of denial of marriage, defiance of social norms, initiation into bhakti, and marriage with the God as life stages to compose poetry and to earn a respectable position within the small-scale societies they functioned (Ramanujan 1999:271–276b). Ramanujan's analysis makes it clear that, whether it is a male or female bhakti poet, the crucial stage in their lives is a liminal state by which they escape the rigidities of their society and culture.

Hawley's ethnographic exposition of reading and singing of the verses of Mīrābai, Sūrdās and Kabīr in the small-scale societies is illustrative of how communities accorded authority and authorship to the verses of bhakti poets. Citing that the 17th-century compilation, the Bhaktamāl of Nabhadas was the first compendium of the lives of the bhakti poet-saints of North India, Hawley shows how many poems display the biographical motifs found in the compendium. It is as if the life of the poet infuses sacredness into the poetry and the poetry justifies the life. The Caurāsi Vaiṣṇava ki Vārtā, another 17th -century text that details the life of Surdās, adapts the core pattern of Kṛṣṇa's life to Sur's. Hawley observes, 'It appears that the poet's life follows the god's, but the Vārtā's true preoccupation is not the tie between life and life but between art and life. Sur's life is retroactively fashioned to follow the order that was given to the poet's collected opus. Once the bond is established, it cancels any suggestion that Sur's poems could have been composed on a purely random, occasional basis, each one appropriate to an event in which the poet participated or to a mood that welled up within him at a given time. Instead, we get a picture of Sur as the author of a whole, sequentially ordered corpus. He becomes the author of the Sūrsāgar in the form that it was known at the Vārtā was composed' (Hawley 2005:37–38). Thus the biography of the poet, poetry, the mythology of the God, and sacred geography mix with one another to establish authorship and religious authority for the poets. Folk songs and folk dramas reinforced the authorship and authority of bhakti poet-saints. Often the performers claimed and superimposed the saints over their own lives, struggles, and religiosity. The names of saints have become household names in their respective regions so pervasively that blind singers are called 'Sūrdās' and women perceived to be independent are called 'Mīrā'.

Having established that the biography of the bhakti saint is inseparable from the texts of the bhakti poetry, if we were to focus on how the bhakti texts established the conventions of their reception, performance and reading, it brings about the vital semantic plane the bhakti poets and their texts occupy in the everyday life of Indians. The transcreations of Rāmāyaṇa in Indian languages clearly thrived on the bhakti traditions of poetry. Kampan's Irāmāvatāram of the 11th century was the first rendition of Rāmāyaṇa in a language other than Sanskrit. Kampan's epic was followed by the 13th century Telugu Rāmāyaṇa of Buddharaja and by the 14th-century Bengali epic of Krittibasa. Tulsīdās's Hindi Rāmāyaṇa, Rāmcaritmānas appeared only in the 16th century. With the spreading of the Rāmāyaṇa, the image of an anti-establishment bhakti saint and his or her loving devotion for Śiva or Viṣṇu gave way to the ideal persona epitomised in the avatār of Rām. Kampan and Tulsīdās extolled the virtues of Sītā as the perfect woman, and they took poetic departures from Vālmīki's version of the story. Tulsīdās's most striking deviation from the traditional story is his introduction of an 'illusory Sītā' who alone suffers the indignity of abduction and incarceration in Rāvan's Lanka while the real Sītā, Rām's inviolable śakti or feminine energy remains safely concealed in the element of fire (Lutgendorf 1991:7a). Tulsīdās's phenomenal achievement is reconciliation and synthesis between tensions of nirguṇa and saguṇa traditions within the bhakti movement. His Rām is at once Vālmīki's exemplary prince, the cosmic Viṣṇu of the Purāṇas and the transcendent Brahman of the Advaidins. What holds different strands of the Hindu philosophical and theological thinking in Rāmcaritmānas is the overwhelming bhakti mood of Tulsīdās' poem, expressed through exquisite musicality. Another text attributed to Tulsīdās, the Hanumān cālīsā ('forty verses to Hanumān'), has attained immense popularity in North India over the centuries. Lutgendorf points out that one of the major themes of Tulsīdās's epic is to bring about the compatibility of the worship of Rām/Viṣṇu with that of Śiva, and Hanumān plays the role of intermediary and bridges the two traditions. Expounders of Rāmcaritmānas support the cause of the connecting of these traditions with their interpretations. Lutgendorf notes that further evidence of the commingling of the worship of Rām, Hanumān and Śiva can be found in the architectural, religious complex of Banaras (Lutgendorf 1991:42–50b). If recitation of Rāmcaritmānas has become the most visible and audible form of religious activity in Banaras and generally in North India, recitation of Suntarakāṇṭam (the beautiful cantos) of Kampan's Irāmāvatāram has become a popular household activity in Tamilnadu. Additionally, Kampan's Rāmāyaṇa is performed as shadow puppet theatre (Tōlpāvaniḻalkūttu) in the Bagavathi Ammaṉ temples of Kerala (Blackburn 1996).

Storytellers, dramatists, singers, dancers, and other performing artists have long recognised the performative quality of bhakti poetry. Scholars reason that the performativity of the bhakti poetry lies in several factors such as the poetry's ability to absorb local folklore forms, lyricism, musicality, adaptation of spoken language and emotional intensity. However, the principal element that contributes to the performative nature of the bhakti poetry is its personal dialogic discourse in which the poet often addresses the self, God and an audience at once. Āṇṭāl and Mahādēviyakka often address fellow women in their poetry. Tulsīdās's Rāmacaritmānas has samvadh (the dialogue between characters addressed to an audience) as part of the narrative structure of the epic. The hymns of Tirunāvukkarasar, Māṇickavācakar, and Tukārām grant different subject positions for their audience, from being an intimate friend to that of a fellow pilgrim. The camaraderie with which the bhakti poetry draws its audience into an intimate space for sharing is unparalleled.

Characterising bhakti as a religion of contact, of close personal communion between devotee and God and among the members of a community of devotees, Cutler points out that the triadic relationship involving the poet, God and the audience is also established in the metapoems called phalaśrutis that explain the benefits of reciting or performing a particular poem (Cutler 1984). Unlike the phalaśrutis of the Sanskrit mantras which list out only the advantages of reciting them, the metapoems of bhakti poetry provide rhetorical devices to register the poet's name, place and thus help them to historicize themselves. Both Lutgendorf and Cutler have demonstrated how the rhetorical structure of the bhakti poetry (Rāmācaritmānas in the case of Lutgendorf and Tamil Śaivite hymns for Cutler) allow ample spaces for their intended audience to participate and identify themselves with the poets while reciting them in the privacy of their homes or attending the congregational performances of the poems in the public places (Lutgendorf 1991, Cutler 1987). The congregational setting and its collectivity were the new social phenomena bhakti poetry ushered into medieval India, inscribed in texts and embodied in drama and life. Participation of the audience in the bhakti poetry is part of expressing bhakti itself. Bhakti, Prentiss says, urges people towards active engagement in the worship of God. She proposes that the term 'devotion' be replaced by 'participation', emphasising bhakti's invitation for involvement in worship and the urgent need of embodiment to fulfil that obligation. Prentiss writes, 'In actively encouraging participation (which is a root meaning of bhakti), the poets represent bhakti as a theology of embodiment. Their thesis is that engagement with (or participation in) God should inform all of one's activities in worldly life. The poets encourage a diversity of activities, not limiting bhakti to established modes of worship—indeed, some poets harshly criticize such modes—but, instead, making it the foundation of human life and activity in the world. As a theology of embodiment, bhakti is embedded in the details of life' (Prentiss 1999:6).

The discourses and critiques of Bhakti

The discourses and critiques of bhakti centre around four topics; 1) modes of bhakti, 2) tensions between intellection and emotion and perceptions of God either as nirguṇa or saguṇa, and 4) the approaches of compendia and the talents of individual poets.

The discourse evoked by a bhāva is yet another trope that makes the devotees participate in the experiencing of the God. There are predominantly four bhāvas (emotional attitude or moods) with which bhakti poets approach their beloved God. Native classification would name the bhāvas of bhakti as 1) Vātsalya-bhāva bhakti (parental love shown to the God); 2) Sakhya-bhāva-bhakti (friendship and love expressed to God); 3). Dāsya-bhāva bhakti (affection and servitude of a slave or a servant shown to God as one's master); and 4) Mādhurya-bhāva bhakti (sweet love of a woman expressed to God as her lover). While this classification applies to Tamil Śaivite and Vaiṣṇavite bhakti poetry, these aesthetic categories can be easily extended to bhakti poetry in other languages, dances and plays. Nārāyaṇa Bhaṭṭathiri (1559–1645), a mathematician, linguist and a poet from Kerala in his celebrated devotional poem in Sanskrit, Nārāyanīyam extended the bhāva to include nindha bhāva (cursing or scolding the God). According to Nārāyaṇa Bhaṭṭathiri, Hiranyakasibu the demonic father of Prahalādh was also an exponent of bhakti because he was constantly thinking of Viṣṇu as an enemy and evoking God's image in his mind. While Nārāyaṇīyam is a 1036-stanza summary of Bhāgvatha Purāṇa, it is also a bhakti composition in praise of Kṛṣṇa of Guruvāyūr (Rukmani 2014). Nāṛāyaṇa Bhattathiri's inclusion of nindha bhāva in the categories of emotion defining bhakti expressions extends the perception of Kṛṣṇa as a generous and forgiving God.

There are several uses of categorising bhakti poetry according to the bhāva they depict. The fact that Periyāḻvar, Kulacekarāḻvār and Tirumaṅkaiāḻvār excel in expressing Vātsalya bhāva (parental love) help us to group a set of poems and identify the individual styles of the poets. The virtual absence of Vātsalya bhāva in Śaivite bhakti poetry informs us about the nature of the gods worshipped in the poems. How Vaiṣṇava poets such Āṇṭāḷ, Kulacekarāḻvār, Tirumaṅkaiāḻvār and Nammāḻvār differ from Śaivite poets Tirunāvukkarasar, Ñaṉacampantar and Cuntarar in handling mādhurya bhāva (lover and lady love) facilitates us in charting the emotional course of religious sects. While we will be able to discern the inter-semiotic plane of women's expression from analysing the mādhurya bhāva poems of Āṇṭāḷ and Mahādēviyakka and their erotic elements, the complete absence of the mādhurya bhāva in the verses of Śaṅkardev in Assam and the actual shunning of the erotic elements in Assam would inform us about the cultural contexts in which these poems thrived.

A.K. Ramanujan viewed the nirguṇa/saguṇa distinction of the God in bhakti poetry as useless since he saw it as a limitation in the understanding of the bhakti poets' creativity. He observed,'The distinction iconic/aniconic is a useful one, as nirguṇa/saguṇa is not. All devotional poetry plays on the tension between saguṇa and nirguṇa, the lord as person and the lord as principle. If he were entirely a person, he would not be divine, and if he were entirely a principle, a godhead, one could not make poems about him. The former attitude makes dvaita or dualism possible, and the latter makes advaita or monism... It is not either/or, but both/and; myth, bhakti, and poetry would be impossible without the presence of both attitudes' (Ramanujan 1993).

However, most of the scholarly discussions in Indian languages on the bhakti poems revolved around the oscillation between God as the person and God as a principle. The emphasis on the nirguṇa and saguṇa ideological distinction in scholarship is complicated by considerations of how bhakti has been understood over time in the Indian context. Scholarship on bhakti as a movement has explored the nature of the poets' responses through the classification of nirguṇa and saguṇa. Contrary to the populist studies, this line of inquiry is explicitly focused on discerning ideologies within the poets' response to their religious contexts. The devotees of saguṇa had strengthened the existing sects and had supported established religious institutions. The devotees of nirguṇa schools had taken a liberal view of accommodating multiple religions into their fold. The followers of nirguṇa schools had been the reformers within the bhakti movement. The nirguṇa-saguṇa distinction affirms an indigenous classificatory perspective; the Tamil Śaiva and Vaiṣṇava bhakti poets are classified as imagining a saguṇa God, as are the North Indian bhakti saints, Sūrdās, Mīrābaī, and Tulsīdās. The Vīrā Śaivas of Karnataka, and the North Indian saints Ravidās, Kabīr and Nānak, are all held to imagine God as nirguṇa (Barthwal 1978).

A related debate about the bhakti tradition would be the tension between emotion and intellection: emotion to reaffirm the social context and free expression, and intellection to ground the bhakti religious experience in a philosophical premise. The general understanding within the Indian discourses on bhakti is that the Bhakti Yoga of Bhagavad Gītā presents an intellectual approach to bhakti. The GItā identified four types of bhakti salvation, which include, and are not opposed to, jñāna (higherknowledge). These types are related to the condition of the person practising bhakti: arta, one who is in distress; jñāsu, a seeker of knowledge; arthārāthi, a seeker of worldly success; and jñāni, a person of higher knowledge. The Bhagavad Gītā favours the jñāni, who thinks of God single-mindedly: the jñāni is ekabhakta. Continuing the saguṇa–nirguṇa distinction, the poetry of the nirguṇa bhaktas was considered to be rooted in knowledge (jñānāshrayi), whereas the poetry of the saguṇa bhaktas was deemed to be rooted in love (premāshrayi). Although centuries ago, Rāmānuja had philosophically reconciled these tensions, these distinctions continue to play a vital role in the minds of practitioners of bhakti even today.

Another crucial derivative discussion of nirguṇa-–saguṇa nature of God was that it was guṇa (qualities of a person/devotee), not jāti (caste) that should determine a person's place in the society. Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay, a 19th-century intellectual sought to modernise and restore bhakti by guṇa theory. Reflecting over Chattopadhyay's reform, Ranajit Guha observed, 'Bhakti, in other words, is an ideology of subordination par excellence. All the inferior terms in any relationship of power structured as Dominance/Subordination within the Indian tradition can be derived from it.' He further wrote,'But, for all its sophistication, this "modernized" Bhakti was still unable to overcome the older tradition. This was so not only because Western-style education and liberal values were so alien to the subaltern masses that they could hardly be expected to take much notice of such positivist-liberal modifications of their cherished beliefs. The reason, more importantly, was that these modifications did not go far enough to question the premises of traditional Bhakti. ... It is the weight of tradition which undermined Bankimchandra's thesis about gun rather than jati as the determinant of Bhakti. Whatever promise there was in this of a dynamic social mobility breaking down the barrier of caste and birth came to nothing, if only because the necessity of the caste system and the Brahman's spiritual superiority within it was presumed in the argument. It was only by emulating the Brahman that the Sudra could become an object of Bhakti. In other words, Bhakti could do little to abolish the social distance between the high-born and the low-born, although some of the former's spiritual qualities might, under certain conditions, be acquired by the latter, without, however, effecting any change of place' (Guha 1992:259, 262).

The major flaw in Guha's argument is that he dismisses an entire movement that has lasted for centuries while assessing one intellectual's attempt to modernise and reform bhakti. Bhakti movement obviously has not abolished the caste system in India, and it has not produced an egalitarian society, but bhakti movement's aspirations in medieval times were aimed towards those ideals. We need to still clearly unearth and study what was the social structure and the underlying ideas and attitudes that gave rise to the bhakti movement of medieval India. We are also yet to examine the relationship between the phenomenal growth of the movement and the rise and expansion of commodity production and domestic trade in medieval India. These studies would not happen if we were to adopt the hagiographic approach of the compendia on bhakti poet-saints such as Periyapurāṇam. Placing all the bhakti poet-saints in one category would not help us understand the historical processes behind the bhakti movement. We need to study each of the bhakti poet-saints in the contexts of their small-scale societies and their historical settings as if they were Hegelian princes bringing about a change in their societies. Only when we focus on the individual bhakti saints in their inherited settings, we would be able to gain beneficial insights into the bhakti movement.

References

Barthwal, Pitambar D. 1978. Traditions of Indian Mysticism Based upon the Nirguna School of Hindi Poetry. New Delhi: Heritage publishers.

Blackburn, Stuart. 1996. Rama Stories and Shadow Puppets. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Champakalakshmi, R. 2011. Religion, Tradition, and Ideology: Pre-Colonial South India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Cutler, Norman. 1984. 'Poet, God, and Audience in the poetry of the Tamil Saints.' Journal of South Asian Literature 19.2:63–78.

———. 1987. Songs of Experience : The Poetics of Tamil Devotion. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Davis, Richard, 2009: A Priest's Guide for the Great Festival Aghoraśiva's Mahotsavavidhi. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Guha, Ranajit. 1992. 'Dominance without Hegemony and Its Historiography,' in Subaltern Studies VI: Writings on South Asian History and Society, ed. R. Guha. New Delhi: Oxford University Press

Hart, George L. 1976. The Relation between Tamil and Classical Sanskrit Literature. Vol. X Dravidian Literature Fasc.2. A History of Indian Literature. Weisbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

Hawley, John Stratton. 2005. Three Bhakti Voices: Mirabai, Surdas, and Kabir in Their Time and Ours. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Jagannathan, Bharati. 2009. Approaching the Divine: Integrating Alvar Bhakti in Srivaisnavism 6th–14th Centuries CE. New Delhi: Primus Books.

Lakshmi, A. 1994. 'Bhakti Movement and Temple Development in Tamil Country from 6th Century AD to 10th Century AD.' University of Madras. http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in:8080/jspui/handle/10603/79013.

Lutgendorf, Philip. 1991. The Life of a Text: Performing the 'Ramcaritmanas' of Tulsidas. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Mani, Vettam. 1975. Puranic Encyclopaedia : A Comprehensive Dictionary with Special Reference to the Epic and Puranic Literature. Delhi : Motilal Banarsidass.

Muthukumaraswamy, M.D. 2012. Trance in Firewalking rituals of Tiraupati Ammaṉ temples in Tamilnadu in Emotions in Rituals and Performances: South Asian and European Perspectives on Rituals and Performativity, eds. Axel Michaels and Christoph Wulf. New Delhi: Routledge.

———. 2015. Vedic Chanting as a Householder’s Meditation Practice In the Tamil Śaiva Siddhānta Tradition in Meditation and Culture: The Interplay of Practice and Context, ed. Halvor Eifring. London; New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Mohammada, Malika. 1975. 'A Study of the Influence of Alvars on the Hindi Krishna Bhakti Poetry of the 16th century.' Aligarh Muslim University. http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in:8080/jspui/handle/10603/65486.

Muller-Ortega, Paul Eduardo. 1989. The Triadic Heart of Śiva: Kaula Tantricism of Abhinavagupta in the Non-Dual Shaivism of Kashmir. The SUNY Series in the Shaiva Traditions of Kashmir. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Narayanan, Vasudha. 'Bhakti.' Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism, eds. Knut A. Jacobsen, Helene Basu, Angelika Malinar, Vasudha Narayanan. Brill Online, 2016. Reference. Universitaetsbibliothek Würzburg. January 15, 2016 <http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/brill-s-encyclopedia-of-h…- BEHCOM_2050060> First appeared online: 2012

Peterson, Indira Viswanathan. 1991. Poems to Śiva: The Hymns of the Tamil Saints. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers.

Prentiss, Karen Pechilis. 1999. The Embodiment of Bhakti. New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ramanujan A.K. 1973 Speaking of Śiva New York: Penguin Books

———. 1993. Hymns for the Drowning: Poems for Viṣṇu. New Delhi: Penguin.

———. 1999. The Collected Essays. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Redington, James D. 1992. 'Elements of a Vallabhite Bhakti-Synthesis.' Journal of the American Oriental Society 112.2: 287–94.

Rukmini, S. 2014. 'Bhakti through Literature: A Study of Poonthanam and Melpathur Narayana Bhattathiri's Literary Works', IUP Journal of English Studies 9.2.

Sanderson, Alexis. 2009: The Śaiva Age — The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period', in Genesis and Development of Tantrism, ed. Shingo Einoo. University of Tokyo.

Shivaprakash, H.S. 1999. 'HERE AND NOW: Poetics of Kannada Vachanas: An Example of Bhakti Poetics.' Indian Literature 43.6:5–12.

Shulman, David Dean, and Guy G Stroumsa. 2002. Self and Self-Transformation in the History of Religions. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

Thakkar, Muktaben Dasharathbhai. 1966. 'Bhakti Cult of the Bhagavata Purana.' Maharaja Sajirao University of Baroda. http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in:8080/jspui/handle/10603/54383.

Thapar, Romila. 2002. The Penguin History of Early India From the Origins to AD 1300. New Delhi: Penguin Books.

Tyagi, Alka. 2008. 'Inter semiotic Transformations: A Study of Works of Two Medieval Indian Bhakti Poets, Akka Mahadevi and Andal.' Jawaharlal Nehru University. http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in:8080/jspui/handle/10603/14673.