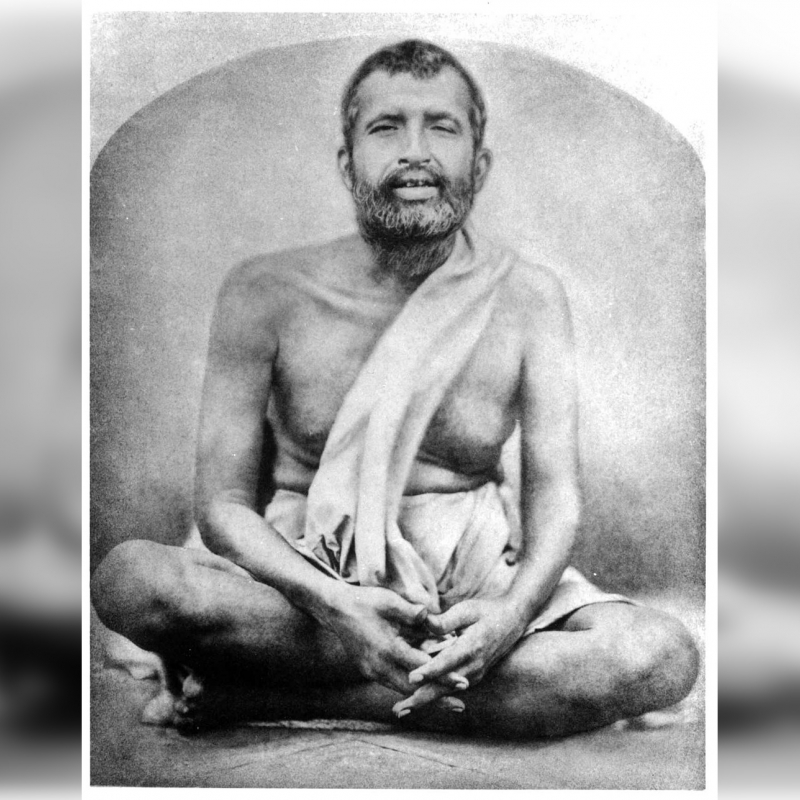

Sri Ramakrishna’s appeal as a religious figure is well known to all Bengali Hindus. Sahapedia attempts to explain this popularity and the enduring appeal of his words. (Photo Courtesy: Author Abinash Chandra Dna. In Wikimedia original uploader was Sray at en.wikipedia [Public domain])

Of the several prominent religious figures in Bengal in recent times, Ramakrishna Paramahamsa (1836–86) has acquired an iconic status. It would not be incorrect to say that during the last century or so, there was scarcely a Hindu home in Bengal without a photograph of the saint alongside those of his wife Saradamani Devi (or Sarada Devi) and his chief disciple, Swami Vivekananda. In the public sphere, the headquarters of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission at Belur (in West Bengal) remains one of the most frequented spots, attracting both the ardent devotee and the itinerant tourist with predictable regularity.

Gaining Popularity

In recent years, Ramakrishna has emerged as a fascinating subject of study for the social and cultural history of his times as well as the inner dynamic of the Hindu spiritual tradition. The first has been the work of social historians, the second, that of scholars of philosophy and religious studies. When seen in the company of comparable contemporary or near-contemporary figures, Ramakrishna appears to have enjoyed three advantages that others, such as Ramprasad Sen (1718–75) or Sadhaka Bamakhepa (1837–1911), did not.

First, there is the matter of his urban location in the colonial metropolis of late nineteenth-century Calcutta, a feature that eluded other prominent figures like Sen and Bamakhepa. This also determined the social face of his numerous devotees and disciples. For some, Ramakrishna’s religion was essentially a ‘religion of urban domesticity’, though this has to be qualified in some respects. For example, though born in an urban milieu, its appeal, eventually, far surpassed this boundary. Second, also vitally connected with this urban life was the success of print media, a development that has contributed substantially to the creation and perpetuation of the Ramakrishna cult over time. Third, with the growth of new ideas about active missionary work and organised religion even within Hinduism, the Ramakrishna Math and Mission was the third successful venture after the Brahmo Samaj and the Arya Samaj. The Ramakrishna order now enjoys a global presence and adopts distinctly modern methods of works—more specifically, publicist networks and proactive social philanthropy—techniques with which Ramakrishna himself would have been quite uncomfortable.

The Iconoclast Swami

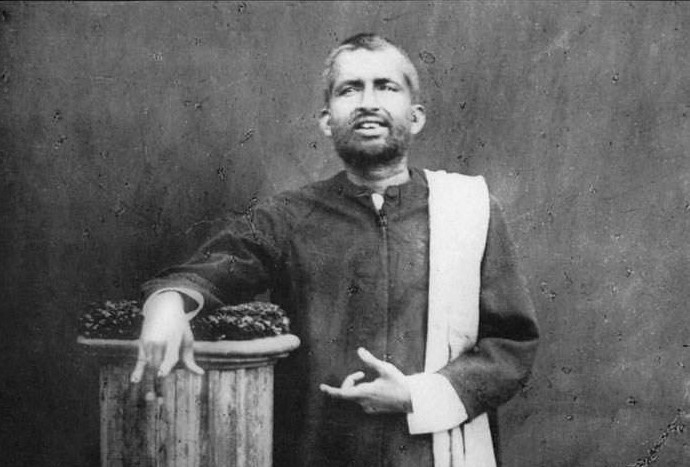

What explains the popularity of Ramakrishna and the enduring appeal of his words? A purely historical explanation—confined to the study of the colonialised social world of the Calcutta middle classes with its typical anxieties—does not suffice. This tends to make Ramakrishna a captive of his middle-class audience, whereas in reality, he was a preacher in his own right; keen to instruct and share his experiences as a sadhaka, or a spiritual practitioner. In his parables and preaching, the essential point of reference was neither man nor woman, the young or the old, the employed or the unemployed, the rich or the poor, but more generally, the samsari—the human being not only located in the material world (the samsara) but deeply implicated in it. In Ramakrishna’s understanding, this took away from God-vision, which was the summum bonum (ultimate goal) of all human life. Ramakrishna once compared routine domestic life to a citadel, within which the moral and material battles of life could be fought most effectively—a training ground, if you will, for ordinary men and women. And yet, he considered detachment and world renunciation to be goals of far greater value. This juxtaposition of social conformism and spiritual transgression is, perhaps, best exemplified by his decision to take a wife but not consummate the marriage.

Sri Ramakrishna’s appeal as a religious figure was considerably enhanced by his recourse to a varied religious praxis, undergoing, by turn, Vaishnava Sakta, Tantric, Christian and Islamic forms of worship, and concluding therefrom that there were as many valid paths to God as there could be opinions. To this he added the claim that religions came from God and were not humanly created. Arguably, this struck at the root of all bigotry, intolerance and zealous self-righteousness. Also important is his avowed rejection of a religious synthesis that randomly fused chosen elements from various religions, as was the case with the contemporary Brahmo preacher, Keshub Chunder Sen (1838–84). All religious traditions, rather than being porous, had to be bound by a given core of beliefs and practices. However, in hindsight, this appears to have strengthened a sense of orthodoxy at a time of sweeping religious experimentation.

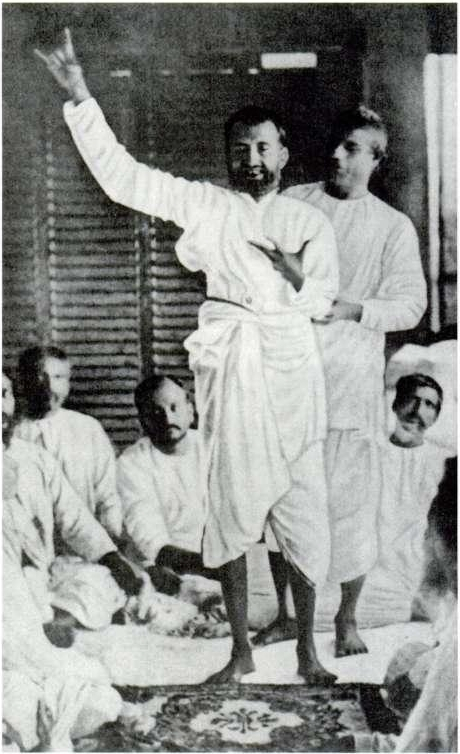

The One-Stop Guru

Ramakrishna also had two other outstanding qualities that made him the figure he was. First, he was a gifted storyteller who communicated profound wisdom in the simplest and most entertaining of languages. Second, he was blessed with acute powers of observation and understood the existential needs of a wide cross-section of people: unemployed youth, aged pensioners, issueless widows, neglected housewives, ill-adjusted couples, people affected by death and bereavement. Quite aptly, he once described himself as a grocer who stocked a variety of goods and merchandise that met the diverse requirements of most. This lies at the root of his continuing appeal.

This article was also published on The Statesman.