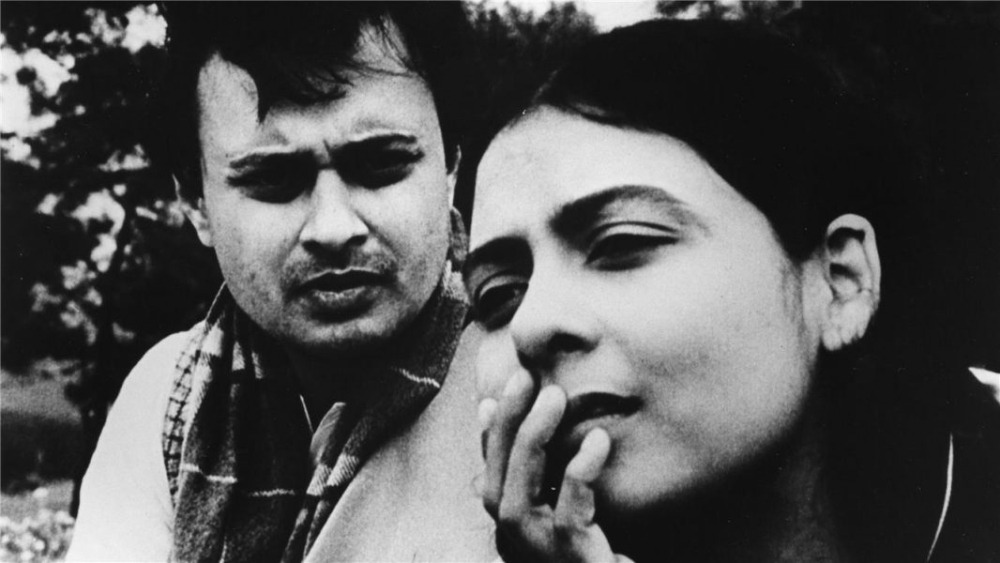

Many say Ritwik Ghatak, often hailed as one of Bengali cinema’s three maestros along with Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen, found the appreciation he deserved only after his death. His genius was not restricted to his films and scripts alone, but went on to influence a generation of film-makers whom he taught at the Pune FTII. We put the spotlight on what his stellar students—now excellent film-makers themselves—remember of him and his work. (Photo courtesy: Scroll)

In 2018, noted filmmakers Kumar Shahani and Saeed Akhtar Mirza met in Delhi for a very special event. They met as students paying homage to a dear departed teacher from the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune. It was the launch of the digitally restored version of Ritwik Ghatak’s iconic Bengali film The Cloud-capped Star, as Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960) is called in English, by The Criterion Collection[1] on their website, which houses the most exclusive of world cinema.

During a conversation between the two at the event, Mirza passionately spoke about The Cloud-capped Star’s ‘enhanced realism’, how it dexterously interweaves elements that are both expressionistic (such as the densely layered soundtrack) and naturalistic (such as Supriya Choudhury’s supremely moving lead performance). Shahani identified a scene shot on the famous College Street in Calcutta (now Kolkata) as a way for Ghatak to draw viewers into the heightened reality of his pathos-filled story.[2]

Also read | The Cinema of Satyajit Ray: In the Prison-house of Humanism

Such glorious tributes to a filmmaker who gained more prominence after his death—Ghatak died in 1976 at the age of 50—goes to show the magnitude of impact the director, scriptwriter, author, and even actor has had on modern Indian filmmaking. Apparently, Shahani was one of Ghatak’s favourite students, and Mirza was bestowed with an additional middle name of ‘Akhtar’ by the Bengali maestro himself, as Ghatak found that the two-word name did not pack enough of a punch. As vice principal of FTII in the 1960s, Ghatak trained many of Bollywood’s mainstream directors, including Subhash Ghai—who was, in fact, an acting student, and his ‘first film’ Fear (as part of the diploma) was directed by none other than Ghatak.

Even though Bengalis might be divided into (Satyajit) Ray and Ghatak camps, Ray himself considered Ghatak as one of Bengal’s finest filmmakers of the 1950s–60s. While he scripted the 1958 blockbuster Madhumati (directed by Bimal Roy, the year’s highest grossing film with Rs 4 crore), Ghatak confined his filmmaking to Bengal. He managed only one commercial hit from his eight feature films, and six films were abandoned due to either funds shortage or his excessive partiality towards alcohol. One such abandoned film includes a documentary on Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in 1972, soon after the Bangladesh liberation. One of his old associates recalls that once Gandhi delayed her flight waiting for Ghatak to arrive for a scheduled interview and shoot at the tarmac of the Kolkata airport, but the filmmaker but never turned up.

How Ghatak’s Influence Lives On

While these incidents might have affected his commercial success, his legacy remains as glorious as ever. Ghatak was a filmmaker’s filmmaker. He even fathered the ‘new wave’ of Indian films of 1970s and 1980s, through his FTII disciples. Shahani and Mani Kaul—the torchbearers of visual and cinematic radicalism in Indian films—were his favourites. So was the rebel of Malayalam films, John Abraham. Together, with other students trained by Ghatak, they created films that broke traditions, excited the discerning audience, thus, heralding a new film culture of visual and narrative aesthetics and technical excellence. These films went on to win national and international awards and acclaim. Shahani is described as the filmmaker who started the ‘formalist’ trend (i.e., staying true to one style of filmmaking) in Indian films and is described as one of India’s finest film scholars. Kaul was deeply influenced by the ‘epic’ format of Ghatak’s films. ‘The epic form is just the opposite (of drama), which means that the narrative is usually very thin, very spread out and at every stage that it develops, it tries to have wider perspectives. Not just concerning the characters but also about nature, history or ideas,’ Kaul once said in an interview with filmmaker Nasreen Munni Kabir ahead of a special cinematic dedication to Ghatak on UK television.[3]

Also read | Cultures of Critical Writing on Film

Abraham, another ardent disciple of Ghatak, talked about learning how to layer ideas or levels in films even while adopting straight narrations. His film Agraharathil Kazhutai (Donkey in a Brahmin Village, 1977) is both in ‘epic’ format as well as an example of layered metaphors. Multilayering of insights and emotions, and social, political and personal dimensions of characters and situations in Ghatak’s films were what attracted most of his students like Abraham.

In a recent interview with this author, filmmaker Aparna Sen talked about the Bengal trio of maestros—Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak—and quipped: ‘Ritwik Ghatak was perhaps not always as consistent in the totality of his films as Ray, but his cinematic frames just took your breath away. His choice of locations and lenses were mesmerising. He also created some beautiful emotional moments in his films.’ An example of this can be when the protagonist Nita of Meghe Dhaka Tara, the lone earning member of the family who sacrificed her life for the welfare of the refugee family in Kolkata, is leaving her house in disgust: we hear the distinctive sounds of the visarjan (immersion) of the Durga idol, as if she had attained divinity in her act of leaving.

Indeed Ghatak, created a gold standard in filmmaking from India, when the country was in search for Indian idioms for films in the 1950s and 1960s. And while mentoring a group of promising students at the FTII, he left a deep imprint on the filmmaking of his students who went on create the ‘New Wave’ in India films. Today, there is a silent cult of Ritwik Ghatak and Satyajit Ray followers in Indian filmmaking, akin to cults of Andrei Tarkovsky and Sergei Eisenstein in the world of Russian filmmaking. Unfortunate that he died early at 50; his films aged like fine wine and over the years spread outside Bengal, film society and film academic circuits across the world. With film bodies and collections digitally restoring his films and archiving them, generation after generation of filmmakers across the world will now have a chance to get inspired in their search for their own contemporary idioms in films.

This article was also published on South Asia Monitor.

Notes

[1] Criterion is an American home video distribution company which focuses on licensing ‘important classic and contemporary films’ across the world. Their website is www.criterion.com.

[2] Ritwik Ghatak’s Pursuit of Truth Beyond Realism, Criterion (September 13, 2019). Accessed January 28, 2021. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/6585-ritwik-ghatak-s-pursuit-of-truth-beyond-realism.

[3] Nasreen Munni Kabir, ‘Ghatak is a lesson in appreciating “Titas Ekti Nadir Naam” and cinema’, Scroll.in, September 15, 2016. Accessed January 31, 2021. https://scroll.in/reel/816540/mani-kaul-interview-on-ritwik-ghatak-is-a-lesson-in-appreciating-titas-ekti-nadir-naam-and-cinema