The following is a chronological study of the history of Bidri:

1422–1600 AD

The history of bidriware is said to have begun with the reign of Ahmed Shah Al Wali Baihmani. The city of Bidar became the production centre for bidri since then. Ahmed Shah Al Wali Baihmani (1422–1436), the ninth king of the Baihmani dynasty ruled for a period of 13 years and was a great patron of the arts. Sultan Ahmed Shah Baihmani and his son Allauddin Baihmani II took interest in promoting and encouraging the arts. During his period “the settlement of Bidar grew into a reputed city and became a ‘Mecca’ for artisans from all over the civilized world” (Census of India 1961, Vol II:3).

After the demise of Humayun, who was the successor of Allauddin Baihmani II, Nizam Shah and Muhammad Shah III ascended the throne of Bidar. Khawaja Mahmud Gawan was appointed the prime minister during Nizam Shah’s and Muhamad Shah III’s reigns. Mahmud Gawan was perhaps the greatest statesman and general to be known in the history of the Deccan (Yazdani 1947:10). Devoted to learning, he also built the Mahmud Gawan Madrasa which functioned like a residential university in the 15th century where various art practices were taught, bidri being one of them.

A conspiracy that led to the killing of Mahmud Gawan deeply affected the state of the kingdom and marked the downfall of Baihmani dynasty. Bidar was then ruled by Barid Shahi's empire until the mid-17th century.

Rangeen Mahal, a palace which has mother-of-pearl inlay was built by Ali Barid (1542–80), and is said to be the artistic inspiration for bidri.

Although bidri is said to have been established during Ahmed Shah's reign, no specific time period of its origin has been estimated yet. No examples of bidri dating to the 15th or 16th centuries have been found in paintings or literature, thus making one sceptical if bidri should still be related to the 15th century or not. However, in that case, the mother-of-pearl inlay could not have been the inspiration for bidri but could have only been a possible representation of it as the time periods do not follow one another.

1600–1650 AD

The first ever known appearance of bidri is said to be in a miniature painting. Jagdish Mittal, a famous painter and collector of Indian art, refers to a miniature dated 1625 in the State Museum of Hyderabad as the first occurrence of bidri in paintings. This painting apparently shows a huqqa (a tobacco smoking contraption) inlaid with silver and brass. Bidri huqqas are the most prominent articles in painting and help us differentiate between various periods.

Tobacco was introduced into Mughal India in 1604 from the Deccan, with the Portuguese having the doubtful privilege of taking the credit for its introduction (Stronge 1985:33). The appearance of bidri huqqas/hookahs in paintings in the early 17th century attests to the fact that bidri was made way before the tradition of smoking huqqas started in the Deccan. Adding local flavour to the tradition in vogue of smoking a huqqa was when the bidri huqqa came into production. The use of gold, silver or brass inlay made it exclusive for the royalties.

Early huqqas were globular with a short and squat neck. They often had a supporting ring at the bottom to prevent it from toppling, these with time were discarded as the base of the huqqa was made flatter for it to stand on its own.

Jagdish Mittal in an interview says, “because my interest is in miniature paintings, I can date a painting whether it is 1610 or 1620 to that precision. Given that sort of approach, early bidris of two metals were never made after 1725, the reason being that brass is a hard metal and it took more time to work on. Prices were rising, to bring down the prices, the craftsmen started doing it only in silver”.

Through bidri represented in paintings, it is evident that objects like pandaan, ugaldaan (spittoon) and the huqqa were a necessity in everyone's lives, yet the use of bidri was fashionable for the upper crust. The various shapes and designs in bidri work seems to have changed with time and usage, yet each piece was crafted gently with great intricacy and detail by each craftsman.

1650–1750 AD

On 18th April, 1656 Aurangzeb laid siege to the city of Bidar and captured the fort. Bidar since then remained under Mughal dominance till the middle of the 18th century. During this period, the art and architecture around the city changed according to Mughal tastes. Mughal designs were based on the Shah Jahan period of decorative arts. A motif seen most often were flowering plants with their petals curled over (Mittal 2011: 24). Mughal designs were very distinctive compared to the Deccani designs. The most beautiful and best known pattern, the ‘Mughal poppy flower motif’ is said to be introduced around 1740 and has since been used in bidri extensively.

Bidri huqqas of variation in shapes were produced during this period. Although Mughal courts did not approve of smoking, yet the habit of smoking huqqa had spread and remained endemic in society. Globular huqqas that were made after 1700 had long necks. The bell-shaped huqqas were first seen in paintings before 1700. Small mango-shaped huqqas were also made in the 1700s. These could be hand-held and were convenient during travel.

1750–1850 AD

By mid-18th century, the rule of the Mughals in Bidar came to an end and Bidar then fell into the hands of the Asaf Jahi Dynasty which continued until the mid of the 19th century.

“The earliest reference of bidri ware is in Chahar Gulshan, a history of India written in Persian in 1759, which in turn is based on a work of 1720, and is now preserved in the India Office Collections of the British Library, London” (Mittal 2011:14).

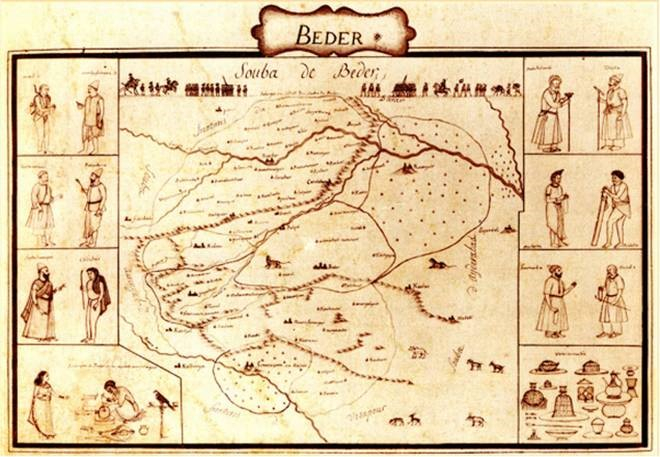

From a series of illustrated works that were concerned with the political and social history of India in 1770, the map of the Subah of Bidar was found tucked away in the India Office Records at the British Library in London. This map shows various bidri articles produced during that time.

Fig 1. A section of the map showing bidri articles produced

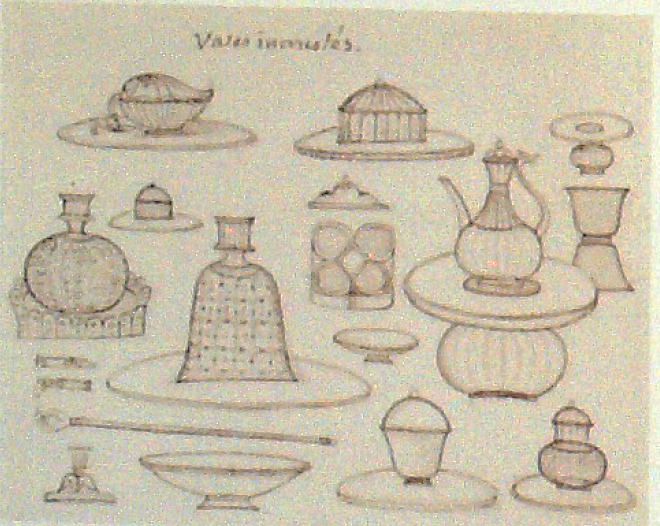

Fig 2. Magnified image of the panel at the extreme bottom-right of Fig 1

This makes it clear that the use of bidri since its early days was to create utilitarian objects. Shapes were determined by their function in Deccani Muslim aristocratic households. A variety of bidri objects were produced which included dishes, abkhora or katora (bowls), aftaba (ewer), surahi (water bottles), pandan and khasdan (boxes for betel leaves), spice boxes, dibiya (small boxes), ugaldan (spitoon), jewel boxes, palang-pae (cot legs), mir-e-farsh (weights for floor covering), shamadan (candelabras), uddan (incense burner), gulabpash (rosewater sprinkler), alam (Shi’a standards), cups with Qur'anic or Shi’a inscriptions in Arabic script, rihal (bookstand), pushtkhar (back-scratchers) and of course, huqqa bases (Mittal 2011:20).

The bidriware found after the 1750s seem to have a European influence due to growing French and British domination. However, bidri craftsmen retained the Deccani flavour until the 1850s, according to Mittal.

After 1800, the ‘skirting’ seen in the bell-shaped huqqas became more prominent. The bud-shaped huqqas started to appear by the end of the 18th century. These could be hand-held or placed on a tripod stand with a circular ring made to hold the huqqa in place. By 1825, huqqas with wasted bodies were seen while some mid-19th century huqqa bases consisted of two parts—the body and a circular base. Bidri work during the period between 1700 to 1800 had seen the finest craftsmanship.

By the early 19th century, bidri started to be produced in other parts of India—Lucknow, Purnea and Murshidabad. Bidri from Lucknow has distinctive features. The inlay with high relief—zarbuland or zarnishan (creating a raised effect)—comes from Lucknow. The double fish pattern was most common in Lucknow bidris, seen, for instance, in the royal insignia of the Awadh Nawab. Bidri at Purnea was expensive to produce and hence we see two types here—gharki bidri (well-finished) and karna bidri (inferior in finish).

Fig 3. Fish shaped boxes from Lucknow

1850–1950

From the early 18th century to the mid-20th century, the bidri industry flourished under the Asaf Jahi rulers. Many artisans from Bidar migrated to Hyderabad, which was the new capital of the Deccan. The art started to flourish in Hyderabad. The Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in London in 1851 followed by the Paris Universal Exposition, 1855 had showcased bidri. Dr. John Forbes Royle, a pioneer of the study of economic botany in India was nominated as the organizer by the East India Company for the Great Exhibition. He was said to be particularly concerned that India should benefit from the exhibition (Stronge 1985:27). This in return not only encouraged the production of bidri but also created a demand for bidri worldwide. It also opened doors for new bidri production centres in India but they were short lived and produced inferior work. After the Great Exhibition, bidri started to be Europeanized for the market. By 1870, Lucknow was full of European tourists during winters which resulted in increased demand of the local crafts. In 1881, bidri from Purnea and Bidar were also illustrated in the catalogue of ‘Eastern Art Manufacturers’. As the taste in bidri changed, the objects demanded were large flower vases, basins, jugs, mirror frames, picture frames, tables, chairs, buttons, walking sticks, cigar boxes, ink stands and visitors’ card cases (Mittal 2011:34).

After 1850, the style of designs inlaid also started to change—the poppy flower design became more and more repetitive. Jagdish Mittal says ‘with each decade, the poppy design became poorer in execution, spacing and feeling’. During the interview he also mentions the design seen in the figure below as the ‘coriander-leaf design’ (kothmiri design). The kothmiri design which is seen 1850 onwards, appears to get more prominent and continues until the 20th century. Even though there is a change in the style after, few extremely fine examples of kothmiri designs can be seen from the 19th century.

Fig 4. Poppy flower in kothmiri design

The bidri industry saw its first downfall in the 19th century. In 1886, the Colonial and Indian Exhibition catalogue stated: “This is an important industry and commands an extensive demand”. The aftermath of the demand created resulted in a decline in standards, the rise of repetitive shapes and patterns, and deteriorating inlay quality.

While until now bidri was associated with household products, another fascinating link that increased its reach and took it further came about through the practice of gifting bidri in dowry. “It could have been totally extinguished from that region also, had it not been for, thanks to the custom of the Mohammedan gentry there, to make a presentation of a complete set of bidriware in marriage ceremonies,” says Sujit Sen (1983:14). This shows that bidri articles were necessarily found in various household as a matter of dignity, seen after the fall of royal and aristocratic families. This trend, however, seemed to have continued only until the 20th century.

Oral histories related to bidri are very rare to find since only the technique of making is transferred from one generation of artisans to the other. However, the mention of ‘Ramanna master’ by Bapu Nagesh, a senior bidri artisan, and Mohammed Ahmed, an 85-year-old bidri artisan are alluring references. In the records of the Delhi Art Exhibition of 1903, Ramanna of Hyderabad was the name of a bidri manufacturer who won commendation for his workmanship (Watt 1903: 52). Further, the Census of India, 1961, mentions the names of Ramanna and Irsangu, who were proficient master artisans from their times. Mittal says, “to retrieve this craft, in 1931 the Nizam's government started a training school for bidri works in 1931 at Bidar with these artisans as instructors. The school was merged with the local High School in 1938” (Mittal 2011:36). Susan Stronge in her book mentions that “in 1950, special units were set up and the Government began to involve itself in training the bidri workers. The Government Artisans Training Institute provided two years training to hereditary bidri workers, giving them a monthly allowance” (1985:31).

1950 onwards

Jagdish Mittal during an interview mentions that his first encounter with bidri was in 1951 in Hyderabad, when he saw discarded household objects being sold on the sides of a footpath. This he mentions was due to the abolishment of the zamindari system in the 1950s which led to those families disposing their art objects due to a sudden financial crisis that arose.

The bidri industry after the 20th century was confined to Bidar and Hyderabad. In the 1956 state reorganisation, Bidar was placed under the state of Karnataka and Hyderabad under Andhra Pradesh (today, Hyderabad is a part of Telangana). Most artisans moved to Hyderabad in search of better livelihoods as it remained a hub for trade.

Variations in bidri could be seen again by the end of the 20th century. Smokers requisites [were] now cigar and cigarette boxes and ashtrays rather than huqqas; also produced are necklace, cuff-links and tie pins. A new development in the production of these article with no useful function whatsoever—wall plaques depicting folk dancers and signs of the zodiac are found, and there are also sculptural pieces which draw their inspiration from the wall paintings of Ajanta (Stronge 1985:37).

Bidri that had gone out of fashion post-independence gained popularity with its new range of products in a few years. “It was a common gifting article in Hyderabad, items like shirt buttons and cufflinks were in fashion” said Mr Sajjat from INTACH Hyderabad in an interview. Even though bidri seemed to flourish in Hyderabad, artisans in Bidar were still left dangling by middlemen. By 2006, the Karnataka Handicraft Development Corporation had applied for the GI (geographical indication) tag for bidri (Desai 2006). However, the much awaited GI tag was given to bidri in the beginning of 2008 (Shaukat 2009).

Susan Stronge mentions a well-observed description of the process of making bidri, as seen by Francis Buchanan in 1809-10 at Purnea, which surprisingly holds true even today. Each stage of the work at Purnea was done by a specialised set of workers, the object passing from one hand to another through different processes. He notes that inlayers and polishers earned the highest wages, with the 'melters and turners' earning very little. The workmen's lives had no security, as they were hired by those who sold the goods on a day-to-day basis as demand dictated (Stronge 1985:21).

The industry of bidri in the 21st century has not undergone many changes. With the establishment of various co-operatives/self-help groups, governmental and nongovernmental organizations are working towards resuscitating the dying craft but its artisans still do not seem to completely benefit from them. Currently in Bidar, the artisans can be categorised into two classes—the first being the National/State/Shilp Guru Award winners versus the rest of the artisans. The latter consists of a greater number of artisans and is also the group that is said to be moving away from the craft. The recognized artisans have not only a deep connection to the craft but also receive a considerable amount of work and consignments on a timely basis. This came forth after a conversation with M.A. Rauf (a National and Shilp Guru award winner), where he mentioned that even if he stops taking orders today, he still has orders to be delivered over the next two years. A similar response was received from Shah Rasheed Ahmed Quadri (Senior National award and Shilp Guru award winner), Raj Nageshwar (National Award winner) and Mr. Saleem, the owner of the website ‘bidrihandicrafts.com’, whereas the rest of the artisans who do not fall under this category either work under the above mentioned people in Bidar or rely on governmental and non-governmental organizations for their livelihood.

Stronge also mentions a short note on the industry at Bidar from the Asiatic Journal, III, March 1817, in which Benjamin Heyne notes that “the men who attended me [i.e. the bidri workers] complained of want, in employment in which former times had been the means of substituting a numerous classis of their own cast [sic], and of enriching the place, but now scarcely yielded food for five families that remained” (in Stronge 1985:24). This condition is still prevalent because the bidri industry which manufactured household utilitarian objects today caters to the needs of tourists, making mostly gifting objects or showpieces. This has resulted in drastic changes in the bidri industry. Therefore, with a change in the target market, the art has also been adversely affected since then and that continues until today. This has eventually led to the disconnect between the artisan and the art, the adverse effect of which is seen with respect to the quality of work. Given below is an example of a poppy flower plant motif from early bidris till today.

Fig 5. Change in poppy flower motifs in chronological order

Fig 6. Poppy flower-bud motif in Mughal design from 18th century versus today

The change in craftsmanship can be evidently seen in the images above. Bidri articles today mostly have wire work, not just in order to cut down the cost but also to reduce time while filling space at the same time. Most articles made by artisans themselves have similar shapes and designs and are kept for sale for tourists but recently, due to collaborations with designers and booming e-commerce ventures, designs are changing according to market demands and preferences.

Today, bidri products comprise necklaces, pen stands, vases, ashtrays, earrings, bangles, card holders, pen drive holders, keychains, wall hangings, boxes, etc.

Fig 7 and 8: Bidri Today

The survival of bidri through all these years is an achievement in itself for the art. However, even today, middlemen are trying to exploit the art in various ways. One such example can be taken from Hyderabad, where fake bidri was produced and sold for higher prices (Desai 2007). Such issues can result is refraining a buyer from purchasing bidri. Hence, for the craft to continue progressing, collaborations between governmental and non-governmental organizations with the artisans need to be made while understanding the potential of the art. Modern developments in products is a great way forward but keeping alive the richness of the patterns and designs innate to the craft will help keep the authenticity of bidri alive for generations to come.

References

Bhowmik, Angshuk. 2010. ‘Adapting to changing times’ The Hindu, Bidar, Febuary 27. Online at http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-features/tp-downtown/Adapting-to-changing-times/article15460309.ece (viewed on December 14, 2017)

Census of India. 1961 Selected crafts of Andra Pradesh, vol. II Part VII-A (3), edited by K.V.N Gowd. New Delhi: Government of India.

Deccan Herald. 2011. 'No shine in it for artisans', Deccan Herald, Hyderabad, July 25.

Desai, Rishikesh Bahadur. 2001. ‘Life of Bidriware artisans looking up’ The Hindu, Bidar, November 1. Online at http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/tp-karnataka/life-of-bidriware-artisans-looking-up/article3041884.ece (viewed on December 19, 2017)

Desai, Rishikesh Bahadur. 2012. ‘Things Looking up for Bidri Artists’ The Hindu, Bidar, April 26. Online at https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/karnataka/things-are-looking-up-for-bidriware-artisans/article3353608.ece (viewed on January 5, 2018)

Desai, Rishikesh Bahadur. 2013. ‘Bidriware finds remunerative prices on the Internet' The Hindu, Bidar, April 27. Online at http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/karnataka/bidriware-finds-remunerative-prices-on-the-internet/article5061802.ece (viewed on January 5, 2018)

Desai, Rishikesh Bahadur. 2013. 2014. ‘Medieval art form gets modern twist’ The Hindu, Bidar, April 8. Online at http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/karnataka/bidri-art-form-gets-modern-twist/article6292645.ece (viewed on December 23, 2017)

Desai, Rishikesh Bahadur. 2016. ‘Helping Bidri artisans reach wider market’ The Hindu, Bidar, April 1. Online at http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/karnataka/Helping-Bidri-artisans-reach-wider-markets/article14620352.ece (viewed on December 23, 2017)

Nanisetti, Serish. 2017. ‘Bidriware imitations everywhere’ The Hindu, Bidar, April 1. Online at http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/karnataka/bidriware-imitations-everywhere/article17760140.ece (viewed on December 23, 2017)

Dutta, Swapna. 2012. ‘Beautiful and breathtaking’ Deccan Herald, Hyderabad, February 18.

Girish, M.B. 2008. ‘Innovative designs help revive Bidriware’ The Hindu, Bidar, March 26. Online at http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/tp-karnataka/Innovative-designs-help-revive-Bidriware/article15191321.ece (viewed on December 23, 2017).

Gulam Yazdani, Bidar-Its History and Monuments, Nizam Government Hyderabad, Oxford press, London, 1947

Mittal, Jagdish. 2011. Bidriware and Damascene Work. Hyderabad: Jagdish and Kamala Mittal Museum of Indian Art.

Narayan Sen, Sujit. 1983. Catalogue on Damascene and Bidri Art. Kolkata: Indian Museum.

Narayanan, Hema. 2015. ‘Black metal magic’ The Hindu, Bangalore, March 10. Online at https://www.deccanherald.com/content/464496/black-metal-magic.html (viewed on January 7, 2018)

Patel, Rehman. 2015. Bidri Art—Inlaid Metal work from Bahmani Sultanate. Bidar: District Administration.

Roy Choudhury, Anil. 1961. Bidriware. Hyderabad: Salar Jung Museum.

Shaukat, Aysha. 2009. ‘Border issues at Bidri’ SpicyIP. February 15. Online at https://spicyip.com/2009/02/spicyip-border-issues-at-bidri.html (viewed on January 7, 2018).

Sivanandan, T.V. 2014. ‘Ancient map of Bidar unearthed in London’ The Hindu ‘Friday Review’ Gulbarga, September 1. Online at www.thehindu.com/news/national/karnataka/ancient-map-of-bidar-unearthed-in-london/article6367374.ece (viewed on December 23, 2017).

Stronge, Susan. 1985. Bidriware: Inlaid metalwork from India. London: Victoria & Albert Museum.

Watt, George. 1903. Indian Art at Delhi. Kolkata: Superintendent of Government Printing.

Yazdani, Gulam. 1947. Bidar: Its History and Monuments, Nizam Government Hyderabad. London: Oxford University Press.