Laharu is a significant figure in the world of Pahari miniature paintings. He came from the Gujarati Manikanth family of painters in Chamba and was active during the reign of Raja Umed Singh (1748–64).

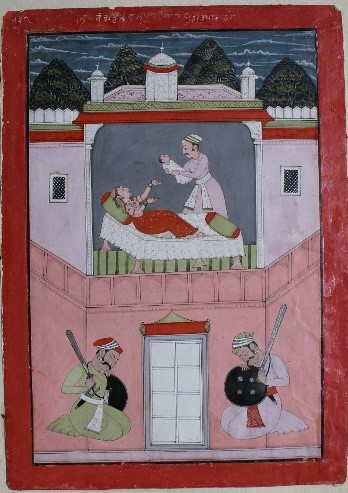

Laharu’s work focuses on the male and female physiognomy and shows utter disregard for the background, which always has a stage set-like appearance. Two of his famous works are the Bhagawata Purana set painted in 1758 for Mian Samsher Singh (the younger brother and Wazir of Umed Singh) and the murals at the Devi Kothi temple. In the Devi Kothi murals, for example, Laharu emphasised on the outer architecture of the buildings even though the stories unfold in the inner chambers. He systematically arranged around the narrative elements such as erect minarets of marble, grids of red bricks and angular pillars. The architectural bodies are proportional to each other, even if they are not so with the human figures they enclose. (Fig. 1) The perpendicular appearance of the buildings enhances their monumental charm, which is evident in the houses and palaces that Laharu painted.

He used isometric perspective, also known as ‘Indian perspective’, to reveal as much surface from a single point of view. It resulted in the placement of buildings in a cubical form with three adjacent walls visible at front. There is a resonance of Mughal-period art in the works of Laharu, which is perhaps because the Manikanth family was active in the Mughal workshop in Lahore before migrating to Chamba. His positioning of elements is reminiscent of the paintings during Akbar’s rule, especially the folios of Akbarnama with the chambers placed on hexagonal planes. The motifs such as the finial, chhatri (umbrella) and the ghuldasta (bouquet) trace themselves to Jahangir’s period.

Backdrops over Backgrounds

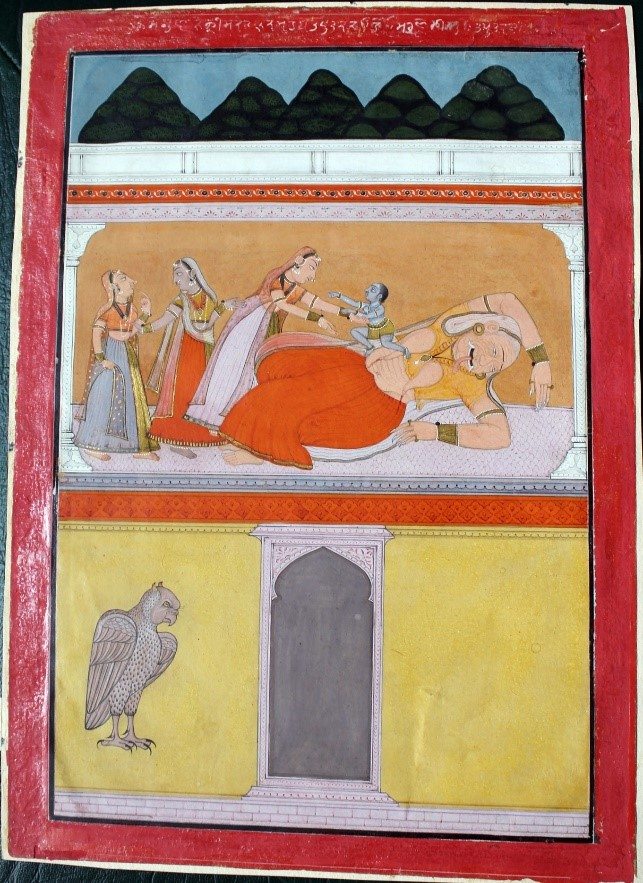

Laharu favoured a backdrop to a background. While the other Pahari painters of his era applied diminishing backgrounds with architectural components and vegetation to suggest perspective, Laharu kept his backdrop flat and devoid of any ornamentation, so that the viewers’ attention is entirely on the lead figures.To add depth to the foreground in Figure 1, two trees are placed behind the building. In Figure 2, a row of trees is set against a cloudy sky that puts further focus on the primary story of Vasudeva handing Yogamaya (the infant) to Devaki. (Fig. 2) Devaki lies on the bed wearing a dhatthu (a headdress), commonly worn post pregnancy by women in the Himalayan region of India.

True to the Bhagavata Purana, the foreground also shows two of Kamsa’s guards sleeping on either side of the prison gate. The conical hills seen farther behind the palace is a hallmark of Laharu’s paintings. The palace, neatly divided into three parts, makes the front of the building look protuberant. The portraits of the guards, with their front-facing visages also allowing a side-glance, bear witness to the painter’s dexterous treatment of faces.

The symmetrical, pyramidal shape of the figures in the painting is hard to miss. Devaki, Vasudev and Yogamaya are at the centre of the top register forming the main plot. They stand out because the dark grey background of the chamber is in contrast to the light pinkish hue of the rest of the building. Because of their positioning, the two opposite walls provide a protruding effect to the chamber. Laharu places two identical guards assuming similar postures on either side of the door below. The two guards mirroring each other divide the painting into halves and allow distribution of space without disturbing visual harmony.

Another mural panel showcases Vasudeva taking away the newborn Yogamaya from Yashoda. (Fig. 3) The composition is similar to Figure 2 in some ways—there is a man, an infant and a mother. The key difference here though is that the characters are horizontally aligned, instead of the vertical alignment we see in Figure 2. The angular hexagonal division of the building also appears flatter and more elaborate. Rows of trees in the background in Figure 2 make way for a monochromatic white background, which acts as a visual device to make the subject matter noticeable without any distraction. Laharu used a limited palette to compose the mural, restricting himself to only primary colours, and focusing on detailing the marble minarets and facades, reminiscent of Mughal architectural motifs.

Separating Spaces

Laharu often employed two background colours to fuse together multiple tales. (Fig. 4) His version of Kamsa trying to kill Yogamaya is a retelling of the legend found in Bhagwata Purana. The character of the washerman sent by Kamsa to kill the infant seems to be entirely Laharu’s invention. In the Purana’s version, the cruel monarch takes up the task in his own hands.

The mural also follows a linear structure of storytelling, which flows from left to right. In the first part, the washerman can be seen about to dash the newborn upon a rock. In the second, the infant, armed with weapons, reveals herself as Yogamaya and rises to the heavens. The force of her ascent is so immense that it rips apart the washerman’s arms. The world of the washerman and the goddess are visibly distinct—while the former resides in the terrestrial world established by the solid clay-coloured backdrop, the latter is in heaven, marked by gathering clouds. Laharu divided the space with such severity that only a part of the ripped arms of the washerman is visible in the upper panel. Laharu repeated this process of breaking spaces to render multiple narratives in many of his other paintings. Describing the painting, ‘Krishna slaying Putana’ (Fig. 5), art historian B. N. Goswamy writes:

Laharu composes the painting in registers, his favourite manner, the middle register being in full view and meant to be seen not as the upper storey of the house but as the courtyard to which the gate in the lower register leads. The dark, pyramidal, mountain-like forms set against the blue sky at the top are Laharu's stylised trees, each filled with discernibly lighter clusters of green. The patterning in the architectural decoration and on the tiled floor of the courtyard is delicately finished.

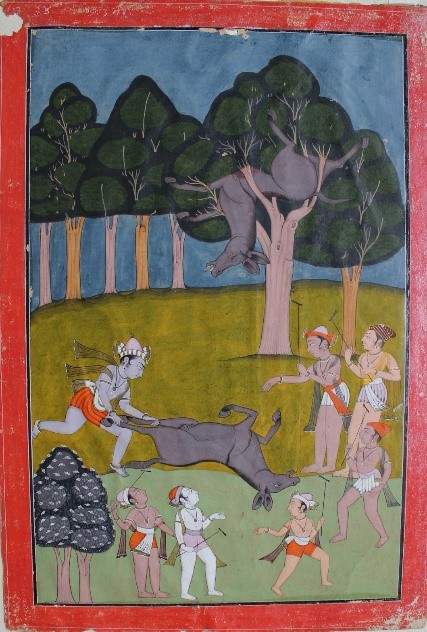

A typical Laharu painting in an outdoor setting includes vibrant figures against a dull and flat background. Instead of resting on a solid plane, the figures appear to be floating against a flat monochromatic surface with no sense of an underlying depth. This strategy is especially useful in paintings that signify movement. In the painting ‘Krishna slaying the demon Dhenukasur’ (Fig. 6), as Krishna slams the donkey-demon on the ground, the gopas can be seen surrounding the combat scene. The women exhibit various expressions of wonder, dismay, worry, angst and joy, and their placement makes this painting exceptional. The figures of the gopas are scattered into three registers—top, centre and bottom.

Art critics suggest that Laharu’s comprehension of perspective without architectural settings is limited. If the figures placed in the bottom register are closer to the beholder than the ones on the top row, the relative proportions of the figures stand contradictory to the argument, as the figures in the top row are much larger. On the other hand, if it is to be considered that the lower gopas are younger in age to those at the top, this logic is defied by the size of the trees in the background, which makes the top-row gopas inhumanly gigantic. It seems that the artist attempted to fill up the empty space in the foreground at the last moment, resulting in the congested placement of the gopas in the lower register. The same problems are not noticed in Laharu's Devi Kothi murals, because the horizontal banner-like arrangement of panels, with figures overlapping each other, restricts experimentation. Although the figures in the mural panels are in rows and registers, they are devoid of perspective devices, which is why every figure appears to be equal in their respective scales.

Laharu, who gave Chamba painting its own distinct identity among the other Pahari schools, continues to inspire miniature painters till date. The present generation of Laharu’s family remains active as freelance artists in Chamba and shares strong stylistic similarities with his oeuvre.

Bibliography

Archer, W.G. Indian Paintings from the Punjab Hills: A Survey of Pahari Miniature Paintings. London: Sotheby Parke-Bernet, 1973.

Coomaraswamy, A.K. Rajput Painting. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1916.

Fischer, Eberhard, Vishwa C. Ohri, and Vijay Sharma. The Temple of Devi-Kothi: Wall Paintings and Wooden Reliefs in a Himalayan Shrine of the Great Goddess in the Churah Region of the Chamba District, Himachal Pradesh, India. Zurich: Museum Rietberg, 2003.

Goswamy, B.N., and Eberhard Fischer. Pahari Masters: Court Painters of Northern India. Zurich: Museum Rietberg, 1992.

Goetz, Hermann. ‘The Art of Chamba in the Islamic Period.’ Journal of the Oriental Institute XI, no. 3 (1962).

———. The Early Wooden Temples of Chamba. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1955.

Ohri, Vishwa C. On the Origin of Pahari Painting: Some Notes and a Discussion. Shimla: Indian Institute of Advanced Studies, 1991.

———. Chamba Painting. Chandigarh: Panjab University, 1976.

Seyller, John, and Jagdish Mittal. Pahari Drawings in the Jagdish and Kamla Mittal Museum of Indian Art. Hyderabad: Jagdish and Kamla Mittal Museum of Indian Art, 2013.