Situated in the high reaches of the Himalayan and Karakoram mountain ranges, Ladakh has developed a highly diverse textile tradition that reflects its physical, socioeconomic and cultural environment. The range of fabrics used extends from simple homespun materials, produced from locally available resources of wool and pashmina, to elaborately patterned prestige garments made from trade textiles. These materials were fashioned into a number of items such as adornments for sacred spaces; containers and coverings for blankets, floors and saddles; and garments worn by men and women.

The variety of textiles available and the weather determine the manner in which Ladakhis dress. Weddings and religious ceremonies are a time to witness the richness and diversity of textiles used and worn in Ladakh—from fine silk-brocades and heavy woollen fabric to robes clinched with tie-dye belts, felt appliquéd capes and velvet jackets in deep tones—which demonstrate continuities with past traditions as well as indicate changing trends and new fashions. (Fig. 1)

History of Textiles and Dress in Ladakh

Little is known about the historical development of dress in Ladakh, and few, if any, early sources and records exist on this subject. Efforts to date the origin of the loom, weaving and textiles are difficult as archaeological excavations have yielded little information.[1] Though Ladakhis believe that the tradition of weaving is an ancient craft, they also talk of a time before the weaving of cloth when their ancestors wore clothes made from animal skins, straw and the bark of trees. Later they learnt how to spin and weave their own clothes. Animal skins are still used in Ladakh to make clothes and most probably dates back to their earlier traditions. Hats (tibi) worn by both men and women are lined with skin from a small goat or sheep (see fig. 1, typically, the black embroidered tibi the woman is wearing would be so lined). In the Leh and Sham areas of Ladakh women wear a goatskin on their back known as slogpa. (Fig. 2) In Kargil a similar garment is worn, known as sthakpa, made from a sheepskin. In winter, among the nomadic pastoralists of the north-east, women wear felt capes (yosgar) lined with skin from the lamb or kid, while men wear a robe (shanlag) made from several sheepskins stitched together with the fur side turned to the body for warmth. Animal skin, especially otter or snow leopard, is also used as trimming for robes, especially men’s, where decorating the edges adds to the attractiveness of the garment and gives the wearer a sense of power and status.

Among the various sources available on the history of textiles in Ladakh, visual ones are of prime importance. Some of the most visible markers of this are the eighth-century deep relief rock engravings at Dras, Mulbekh and the Suru valley. They are largely of Buddhist deities and their devotees, most of them clad in the costume of Indian ascetics, usually a dhoti, an unlikely garment to have been worn in Ladakh. However, at the feet of the Avalokiteshwara image at Mulbekh, while the female devotees are wearing a half-sari, the male devotees are wearing long robes with sashes, typical to those worn in Ladakh today, and one wears a hat similar to the tibi. At Dras, there is the figure of a horseman wearing a long-sleeved, short jacket over trousers and boots, holding a sword in his right hand. This is more likely the outfit of a Central Asian soldier and probably not a replication of garments worn in Ladakh at that time.[2]

Wall paintings are also a valuable source of information on the history of dress in Ladakh. At the monastery of Alchi, dating to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the ceiling and wall paintings document the flourishing trade history of Indian and Central Asian textiles as they demonstrate a variety of techniques, motifs and styles with roots in Central Asia, India, Iran and the Near East. At the three-storey Sumstek temple, men and women wrapped in woollen shawls, clearly a product of Kashmir, are evident along with men wearing cotton turbans and long robes adorned with chequered ornamentation or Sassanian roundels.[3] Central Asian influence is also evident in the long kaftans, trousers and short boots.[4] Textile patterns painted on the ceilings reference brocade, lampas, embroidered and tie-dye fabrics. They are repeated on garments worn by the deities, aristocracy and donors portrayed in the murals, providing confirmation that these reproductions of textiles are not a figment of the painters imagination, but that they were in actual use at the time when Alchi was being built and decorated or at least they had been seen by the artists in the eleventh century and later. One male figure near the Green Tara is said to be a Ladakhi king with his attendant; he is shown wearing a robe similar in style to those still worn.

With the arrival of missionaries, explorers and British officers who journeyed to Ladakh from the seventeenth century onwards, written records and information concerning this subject emerges. The earliest reference to Ladakhi garments is made by the Portuguese Jesuit priest Franscisco de Azevedo, one of the first European travellers to Ladakh in 1631, when he had an audience with the King Sengge Namgyal, remarking that he and the queen wore a garment of some red material.[5] The first photographs taken in Ladakh emerge towards the end of the nineteenth century, and from then onwards there is a steady documentation on the subject of dress.

Dress in Ladakh

Nambu is the main fabric woven in the region, made from wool in a simple twill weave. It is made on a backstrap loom by women among the nomadic pastoralists and on a foot loom by men in other parts of Ladakh where agriculture is practised.[6]

Apart from wool, various types of textiles that entered Ladakh through trade were also used to make garments. Most of these imported textiles were high-profile commodities, their prohibitive costs making them luxury textiles that few could afford. (Fig. 3) Throughout Ladakh their exclusivity made them symbols of status and their use was restricted to the royal family, nobility and the clergy.[7] While silk-brocade from China was especially popular with the Buddhists as it is patterned with Buddhist symbols that ensured blessings and protection to the wearer. (See fig. 1). Muslims preferred to wear kinkhwab from Varanasi or silk-ikats that came from Central Asia.[8] Corduroy and velvet were also popular.

The basic design of male and female robes is the same throughout the region.

The Male Robe

Men in Ladakh wear a full-length robe, commonly known as the gos or goncha. The style of the male robe worn in Ladakh is said to have been influenced by the Tibetan pot-zo, Chinese gyazo and Mongolian sokzo robe designs that, over time, developed into a local aesthetic.[9]

The robe overlaps on the right side and is buttoned from the left shoulder down the length of the robe. (See fig. 1) It has a Chinese-style collar and knee-length slits along the sides. The robe is secured by a wide belt around the waist from which men hang an assortment of implements such as a knife, spoon and needle-case. Often the front part of the robe blouses over the belt and acts as a pocket in which men keep things such as a cup, dried apricots and money. Under their robes men usually wore shirts, and below a pair of loose-fitted straight trousers, woollen in winter and cotton in summer.

Towards Kargil and in parts of Nubra where Muslims live, men also wear a long-sleeved robe (choga) that has a front opening. (Fig. 4). It has no buttons and is usually worn over a long-sleeved, knee-length top (Urdu: kameez) that is visible through the opening. The choga is said to have been derived from Baltistan and Central Asia, and probably also influenced by the courts of Mughal India.

The Female Robe

Women in Ladakh wear a full-length robe known as the sulma. The design of the sulma is said to be a local style that developed in Ladakh, but possibly with some influence from Tibetan and Central Asian garments. This has a round neck and long sleeves, and is fitted on the top with gathers (sul) around the waist and knee-length slits. The skirt of the dress is fairly wide and voluminous, allowing women the agility they require while working in the fields or their homes. The robe has no buttons and is held together by a narrow belt that tightly clinches the waist. Under the robe women wear a loose, long-sleeved blouse (greslen) that has a soft collar that rolls over the neck of the robe. The sleeves of the blouse also roll over the sleeves of the robe, folding over into a wide cuff. In Kargil, women also wore men’s shirts under the sulma; these were popular because of the closed collars.[10]

Below the robe women wear trousers made from the same nambu in winter; for summer they wore loose cotton trousers (rdochaks)—similar in appearance to the churidar worn in parts of northern India—styled such that the leg of the trouser is exceptionally long and so the part between the knee and ankle has several gathers.

Muslim women also use nambu to make the phiren, a long-sleeved, knee-length blouse with a short front opening. Similar to the man’s choga, it is said to have its origins in Kashmir and Baltistan. It is a loose-fitting garment, unlike the sulma, which is fitted on the top and clinched around the waist.[11]

Colour Prescriptions and Accessories

Colour prescriptions stated that nambu be worn in natural colours, with men wearing white and women black or brown.[12] An explanation offered for this was that it could be because throughout the day women are working (in the fields and in their kitchens) and if they wore white the dirt would show up on it. Also, it was only the married women who wore black, unmarried women usually wore white, and black was not worn at weddings. However, some dyeing was done in the Leh area using natural dyes, but little in Kargil, those who wanted to dye their fabric would usually send or take it to Leh and get it dyed there by one of the professional dyers (tshosmkhan).[13] This changed in the early twentieth century when aniline dyes became available, thus enabling people to easily dye their own fabric. Popular colours were brown, maroon or a deep red.

Colour prescriptions were also mandated by the king. In the past, wearing dyed or coloured garments was a sign of status. (Fig. 5) It was the prerogative of the nobility and the clergy; the rest of the population was dissuaded from wearing dyed cloth. It was the same with textiles that entered Ladakh through trade. Only the royal family and aristocrats were allowed to use it for their robes. Common people used fragments of these fabrics to line the inner cuffs of their sleeves and slits or their robes, and the inner side of the collar on the male robe. Called chaga, these were generally made from brightly coloured fabric so they would contrast with the colour of the robe. For more formal occasions the outer edges of the cuffs of the sleeves and slits of the robes were embellished with a narrow piping (known as hashi), about one to two inches in width, made from silk and/or brocade. A border of the same width may also be embroidered, using finely spun woollen threads, directly on the woollen cloth.

Changing Trends in Contemporary Ladakh

In recent years, textile traditions and dress in Ladakh have changed and transformed. Education, accessibility to travel outside the region, growing military presence, tourism, media, Bollywood, changing fashion and social trends have all been factors responsible for this change.

Bazaars in Kargil and Leh now offer the discerning buyer a wide variety of machine-made fibres and fabrics, and readymade garments. While men prefer to wear trousers and shirts or T-shirts, older women tend to wear the shalwar kameez (loose trousers worn over a knee-length blouse), at times on its own or under their sulmas. Western-style dress, popular among younger Buddhist women in the Leh area, is still not widely worn in Kargil probably because of conventions of religion and conservatism. In the Leh area, with a greater awareness of the impact on the region’s ecology and wildlife, the Buddhist clergy have told people to stop wearing animal skins, especially if the animal is killed to make the garment. Artificial skins are now increasingly being used instead.

Towards the end of the twentieth century it looked like there was a decline in people’s preferences for wearing local dress, especially among the men. Also, nambu was harder to come by, as there was a shortage of local wool and decline in the number of weavers, especially among the men who worked on foot looms.[14] Prices escalated and people found it far cheaper to buy readymade clothes than get a nambu robe made.

Concerned about the decline, organisations such as the Ladakh Buddhist Association (LBA) and Women’s Alliance attempted to enforce a rule making it mandatory to wear traditional clothes at religious festivals and public gatherings throughout Ladakh. While both organisations tried to impose this rule, it had not been formalised in any manner. In 2019, the newly formed Union Territory of Ladakh made it mandatory for Ladakhi dress to be worn by government staff on a designated day of the week.

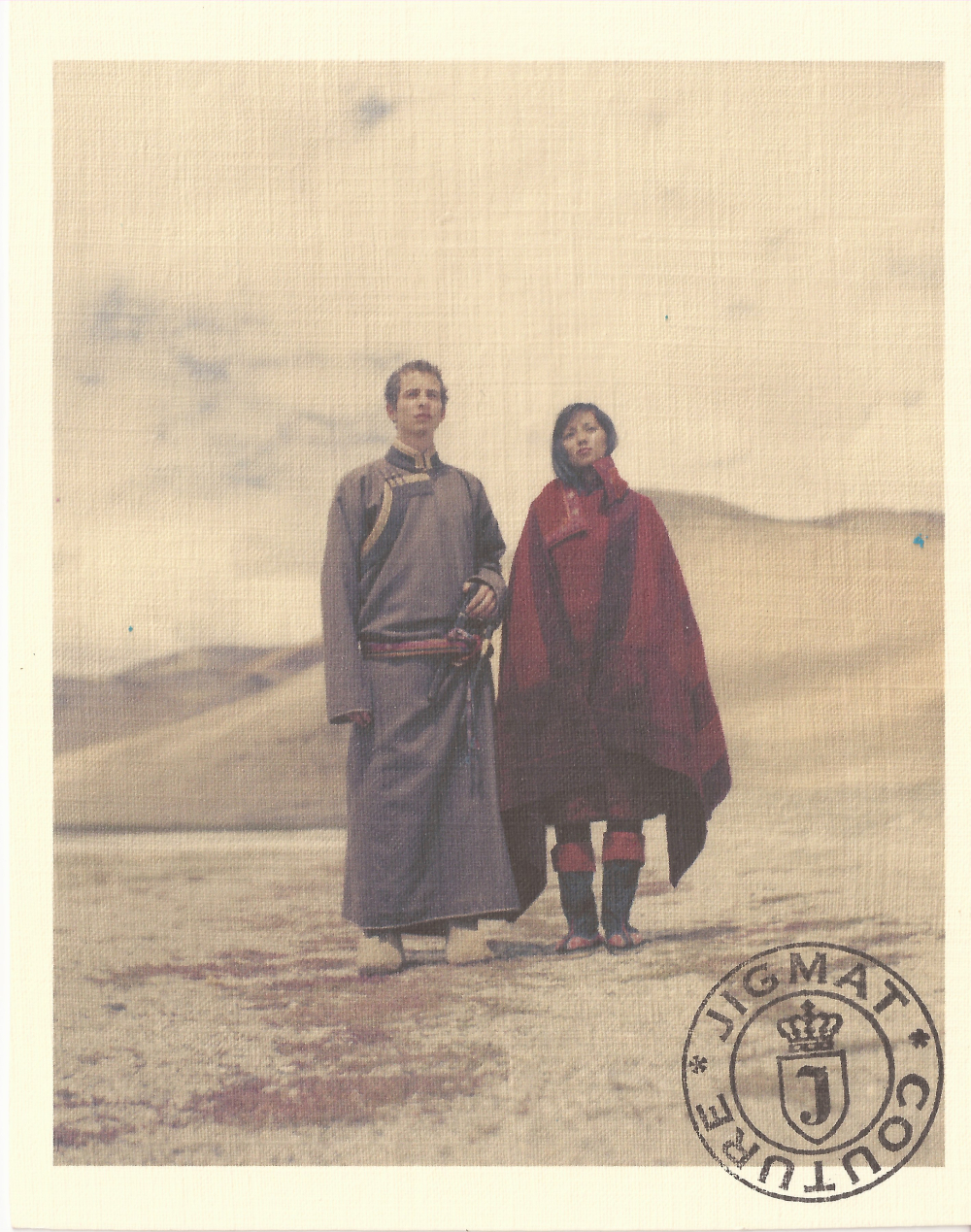

While formal cultural and social events or religious functions have somewhat saved traditional dress, it is the visible resurgence of pride in local dress that has revived it. A number of young Ladakhis have studied at design schools in other parts of India, working with both traditional design and new patterns inspired by them, thus forging a new vocabulary in dress for the region. Keeping the inherent structure of the robes they have experimented with a variety of fabric and embellishments. (Fig. 6) The Ladakhi dress they make is now much sought after by the fashionable and coveted by brides. Though it comes at a price, it has certainly led to the elevation of the status of traditional garments.

In addition, breaking taboos to prevent the craft of weaving from disappearing, women have quietly stepped in and are now weaving nambu on foot looms. Workshops have also been set up that employ mainly women to weave the nambu.

Dress in Ladakh contains evidence of the particularities of the place as well as its links to other lands through the ages. As long as the next generations take pride in their traditions as well as innovations around them, Ladakhi dress will continue to flourish.

Notes

[1] Clay spindle whorls have been found at Neolithic sites on the Tibetan plateau suggesting that weaving of some sort probably existed during that time. Myers, Temple, Household, Horseback: Rugs of the Tibetan Plateau, 21.

[2] It is possible that the trouser came to Ladakh from Central Asia where the garment is said to have first been developed in the third century BC, and is linked to the domestication of the horse; Anawalt, The Worldwide History of Dress, 127.

[3] Ahmed, ‘Textile arts of Ladakh – Nomadic Weaves to Silk-Brocades,’ 70.

[4] Goepper, Alchi, Ladakh’s Hidden Buddhist Sanctuary – The Sumtsek, 266.

[5] Wessels, Early Jesuit Travellers in Central Asia 1603-1721, 109–10.

[6] There are taboos that prevent women from weaving on the foot loom (Ahmed, Living Fabric: Weaving among the Nomads of Ladakh Himalaya, 14-15).

[7] Ahmed, ‘Textile arts of Ladakh – Nomadic Weaves to Silk-Brocades.’

[8] Ahmed, ‘Duguma’s Legacy: Sacred Textiles of Ladakh,’ 34.

[9] Personal communication, Jigmat Norbu of Jigmat Couture, Leh, 2019.

[10] Personal communication, Kaneez Fatima, Delhi, August 2008.

[11] The phiren has increasingly replaced the sulma in Kargil as the latter is perceived as the dress of Buddhist women. Further, because the upper part of the sulma is fitted it is considered inappropriate for Muslim women to wear.

[12] See Ahmed, Living Fabric, 106–9, for a discussion on colour prescriptions in Ladakh.

[13] These dyers used natural dyes made from mineral pigments and organic dyes such as madder, wild rose leaves, indigo, walnut and soot; Ahmed, Living Fabric, 105.

[14] Education has also meant that fewer children are ready and willing to accompany the livestock on their daily grazing rounds. Men have also moved away from professional occupations such as weaving, dyeing and tailoring, turning instead to the new jobs available in the army, tourism and government sector. Instead tailors from northern India, mainly from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, have set up shop in the bazaar are offering these services.

Bibliography

Anawalt, Patricia Rieff. The Worldwide History of Dress. London: Thames and Hudson. 2007.

Ahmed, Monisha. Living Fabric: Weaving among the Nomads of Ladakh Himalaya. Bangkok: Orchid Press. 2002.

———. ‘Textile arts of Ladakh – Nomadic Weaves to Silk-Brocades.’ In Ladakh - Culture at the Crossroads”, edited by M Ahmed and C Harris. Mumbai: Marg Publications. 2005.

———. ‘Duguma’s Legacy: Sacred Textiles of Ladakh.’ In Sacred Textiles, edited by Jasleen Dhamija. Mumbai: Marg Publications. 2014.

Goepper, Roger. Alchi, Ladakh’s Hidden Buddhist Sanctuary – The Sumtsek. London: Serindia Publications. 1996.

Myers, Diana. Temple, Household, Horseback: Rugs of the Tibetan Plateau. Washington: The Textile Museum. 1984.

Wessels, C. Early Jesuit Travellers in Central Asia 1603-1721. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. 1924.